Featured Articles

Remembering the late Craig ‘Gator’ Bodzianowski, Boxing’s One-Legged Wonder

Remembering the late Craig ‘Gator’ Bodzianowski, Boxing’s One-Legged Wonder

It is a really old joke, so much so that you’d have to figure that Henny Youngman and Jack Benny were telling it when they were young comedians on the burlesque circuit nearly a century ago. But there is always an exception to every rule or punchline, the foremost for the purposes of boxing history being its sole contrarian to the oft-repeated proposition that an inept person is “as useless as a one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest.”

The late cruiserweight contender, Craig “Gator” Bodzianowski, who was a one-legged man, didn’t mind poking a bit of self-deprecating humor at his disability as the occasion warranted. When Bodzianowski was asked why he did not seek financial damages through legal means from the driver of the automobile that slammed into his motorcycle, resulting in the amputation of his mangled lower right leg, the impish former Chicago Golden Gloves champion would wink and say, “I can’t go to court. I wouldn’t have a leg to stand on.”

Bada-bing.

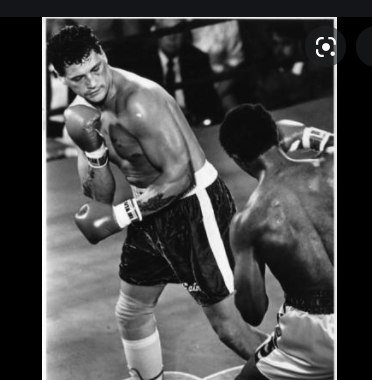

Monday, July 19, marks the 21st anniversary of Bodzianowski’s unsuccessful yet indisputably heroic bid to make the seemingly impossible possible. Perhaps he wouldn’t have defeated WBA cruiserweight titlist Robert Daniels had he the benefit of two fully functional legs, but his longshot quest in Seattle’s Kingdome was made more difficult when a Daniels powershot re-fractured a previously broken rib in the second round, hampering Bodzianowski until the final bell. Although it became increasingly evident that Bodzianowski had no chance to win on the scorecards (Daniels was a wide winner on points, by margins of 119-110 and 118-109 (twice), the battered challenger, his left eye completely swollen shut, refused to yield and finished on his feet.

Bodzianowski – his nickname owed in part to his family’s limited finances during his adolescence and in part to his apparent failure to distinguish between large reptiles of similar appearance — was not disposed to crack wise about what he still was able to accomplish in the ring, before, during and after he made what was arguably his sport’s most remarkable comeback while fitted with a prosthesis where a significant portion of the extremity he had been born with had been surgically removed.

The Bodzianowski family, its suburban Chicago-area home notwithstanding, had a backyard that housed a menagerie of baboons, pigeons, chickens, snakes and even an alligator. Craig soon took to calling himself “Gator” not because of that particular reptilian pet, but because of the Lacoste polo shirts so in favor at the time, with the little alligator (actually a crocodile) embroidered on the left side of the chest. Those shirts were too pricey for parents Pat and Gloria Bodzianowski to purchase in multiple colors for their four sons, so Pat, a tattoo artist, inked the iconic symbol on Craig’s chest and Gloria cut out little rectangles of cheaper Ban-Lon shirts, exposing the tat.

That homemade tattoo served as Craig’s most singular mark of identification, at least until he was fitted with his prosthesis.

“I never, ever say, `Darn, if I had my real (leg), I could have been on top a long time ago,” Bodzianowski said of any might-have-beens that less-determined individuals would have considered had they found themselves in his situation. “I may have. But I don’t look back on that, ever. Not one time. Because I kick ass the way I am now.”

Given his steadfast refusal to give up on life or his dream of becoming a world champion, the most shocking part of Craig Bodzianowski’s inspirational journey is that the body part that ultimately failed him was the organ that kept him going when nearly everyone had told him he would never box again, or should not even make the attempt. He was just 52 when, the night of July 28, 2013, he suffered a heart attack and died in his sleep.

Hollywood loves tales of underdogs who beat the odds, but the fight flick that could have been made about Bodzianowski’s one-of-a-kind comeback never gained traction in La-La Land, if indeed such a pitch ever was made. Perhaps some studio bigwig would have green-lighted a script had the scrappy amputee furnished the requisite exclamation-point finish against Daniels, but he didn’t, and so what if Bodzianowski rebounded from that disappointment to win his last seven bouts to retire with a commendable 31-4-1 record with 23 wins inside the distance?

It says much about the impermanence of fringe-level celebrity that ESPN boxing writer/commentator Mark Kriegel, in his blurb review for my 2020 anthology, Championship Rounds, mentions Bodzianowski in passing as a fighter most readers have never heard of, although they would do well to try to find out about him.

Bodzianowski was building a reputation in the Chicago area as a fighter worth following, winning his first 13 professional bouts, 11 by knockout, when, on May 29, 1984, while driving his Kawasaki 440 at a mere 15 mph, the driver of a parked car suddenly pulled ahead of him, attempted a U-turn and smashed into his bike.

In an instant, the 23-year-old of Polish extraction discovered the hard way why bikers are 25 times more likely to suffer death or serious injury than those involved in car crashes. The list of fighters whose lives or careers were ended by motorcycle mishaps is long, both predating and postdating Bodzianowsk: 1996 IBHOF inductee Young Stribling was 28 when he died from injuries he incurred on Oct. 3, 1933; middleweight contender James Shuler, 26, he perished on March 20, 1986, after is cycle collided with a tractor-trailer; former IBF super featherweight and WBC lightweight champ Diego Corrales, 29, took the eternal 10-count when his bike, traveling at an estimated 100 mph, crashed on May 7, 2009, and two-division world champ Paul “The Punisher” Williams, 26, was paralyzed from the waist down when his bike crashed on May 27, 2012.

“If I could change time, I would,” Williams told Joseph Santoliquito for a 2015 story. “But I can’t, so I have to deal with it. If I wasn’t able to deal with it, I probably would have committed suicide by now or would be angry and depressed all the time. I do feel there are two sides of me: who I was and who I am.”

Somewhat amazingly, Bodzianowski was determined never to look back in regret or self-pity. What happened, happened, and there was no changing it. He would live in the present and look to the future, whatever that might hold. And he was determined it was a future that still included boxing, all predictions to the contrary notwithstanding.

Told that his choices were to have his right leg amputated several inches above his ankle or undergo the possibility of as many as 12 operations over two years, after which he likely would forever walk with a cane and have no more than 70 percent use of the leg, Bodzianowski immediately informed the doctors attending him, “Adios, cut it off.”

That could have and probably should have been the end of Craig Bodzianowski the boxer. But, after a nine-hour surgery and with the benefit of an advancement in prosthesis technology known as the “Seattle Foot,” Bodzianowski showed that his physical limitations were not necessarily as limiting as was widely believed.

“Look, I could have been hurt a lot worse,” Bodzianowski said in 1985. “I could have lost an arm, both legs. I consider myself very, very lucky.”

He slowly began to build upon that semi-good fortune by beginning with a regimen of standing on his artificial leg for hours each day. Once he felt comfortable with that, he’d jog a few steps. Over time, he bumped the distance up to three miles every other day, with a mile run in between.

The next hurdle to be cleared was convincing different groups of physicians that he was, indeed, fit enough to resume his boxing career. There were skeptics, to be sure; Dr. Ferdie Pacheco, Muhammad Ali’s longtime personal physician who later served as a boxing analyst for NBC and Univision, said that, while he admired the “courage and determination of this young man to continue in a dangerous sport, I question and I’m amazed by the lack of judgment and common sense of the boxing commissions and licensors. If this young man should be seriously injured in this sport, where would the commission go hide to avoid the rain of censure falling on its head. The hue and cry, `Ban boxing,’ would be heard throughout the land and I might be the guy to lead it.”

By and by, however, Bodzianowski demonstrated to various state commission-appointed doctors that he was indeed fit enough and mobile enough to be afforded the opportunity to succeed or fail inside the ropes, where it mattered. In his first comeback fight, he knocked out Francis Sargent in two rounds on Dec. 14, 1985. That would be the same opponent he faced in his last pre-accident bout, which he won via 10-round unanimous decision. It was admittedly a tiny sample size, but at first glance it appeared as if the Gator had not only come back, but possibly even a bit better.

“Hey, I was never that graceful when I had two good legs,” Bodzianowski reasoned. “I sort of shuffled side to side.”

In addition to Daniels, Bodzianowski’s other losses came against former WBC cruiserweight champion Alfonzo Ratliff (twice, both by majority decision) and future IBF cruiser ruler James Warring. Given his handicap, the fact that his only four defeats, all on points, came against current, former and future world titlists makes his saga all the more compelling.

“Only in America can a one-legged man fight for the world title!,” mega-promoter Don King harrumphed before Bodzianowski challenged Daniels, the chief undercard bout of a show headlined by two-time former heavyweight champion Tim Witherspoon’s 10-round majority decision over Jose Ribalta.

Ratliff, winner of both of his matchups with Bodzianowski, also came away impressed. “I’ll say one thing about knocking Craig down, he always gets back up,” Ratliff said. “I think the guy’s crazy! He’s such a sneaky fighter that it looks like he’s not throwing hard punches, but the punches are short and they got all his weight in them. He can hurt you. All his punches hurt you. I’ll tell you, that’s the hardest work I’ve had in my life. Craig Bodzianowski, all he knows is to keep coming forward.”

After stepping away as an active fighter, Bodzianowski trained fighters for a while and worked in construction. Always handy in the kitchen, he went on to graduate from Chicago’s Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts in 2012.

Enduring fame, however, can be fleeting. The novelty of the one-legged fighter who rose near the top of his profession but didn’t quite reach the pinnacle faded. Guest spots with David Letterman, NBC Sports and Inside Edition, as well as an 18-minute documentary of his life and career, Against the Ropes, came and went. More recent fighters with fresh stories emerged. The news cycle always replenishes, unless you are a Muhammad Ali (who attended the Daniels-Bodzianowski fight), Mike Tyson or someone of that stripe.

But Craig Bodzianowski deserves to be remembered, if simply for the bottomless depth of his resolve if not his skill-set, and for the magical, mystery quality of the human spirit he so exemplified.

—

A New Orleans native, Bernard Fernandez retired in 2012 after a 43-year career as a newspaper sports writer, the last 28 years with the Philadelphia Daily News. A former five-term president of the Boxing Writers Association of America, Fernandez won the BWAA’s Nat Fleischer Award for Excellence in Boxing Journalism in 1998 and the Barney Nagler Award for Long and Meritorious Service in 2015. In December of 2019, Fernandez was accorded the highest honor for a boxing writer when he was named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame with the Class of 2020. Last year, Fernandez’s anthology, “Championship Rounds,” was released by RKMA Publishing.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review1 week ago

Book Review1 week agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers