Featured Articles

The One Punch KO Artist

When the discussion turns to one punch KO artists, Ernie Shavers comes immediately to mind—and then, upon some reflection, so does Mike Tyson, Sam Langford, Joe Louis, Bob Satterfield, and a bunch of others:

John Mugabi, Thomas Hearns, Ruben Olivares, David Tua must be included in any list and so should big boppers like the Klitschkos, Foreman, Liston, Baer and perhaps Jeff “Candy Slim” Merritt, Herbie Hide, Jaime Garza, Edwin Valero, Khaosai Galaxy and Ricardo Moreno.

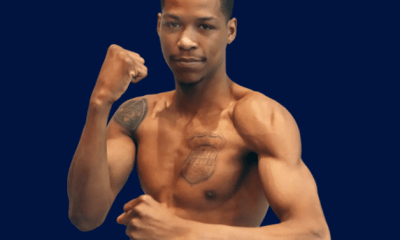

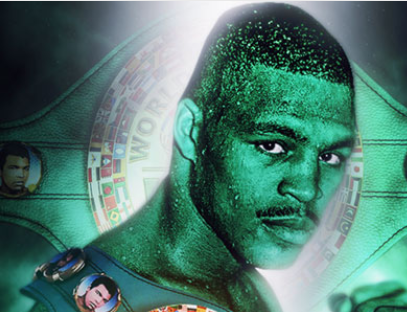

However, two come to mind front and center for this reporter: Julian “The Hawk” Jackson and Gerald “G Man” McClellan (pictured). And if The Ring magazine sees fit to rank them 25 and 27, respectively, as it did in its updated September 2018 list of the greatest punchers of all time, then I submit that The Ring needs to go back to the drawing board.

The Hawk

“Julian Jackson was the hardest pound-for-pound puncher in human history. He relied on it time and time again, one punch was all it took. At any time from either hand a showstopper could come from nowhere. But his god given power came at the cost of ending up on the wrong end of a few vicious knockouts. Those that live by the sword die by the sword.” – Rhythm Boxing

For sheer ability to consistently stun and paralyze an opponent with one single shot, few were more lethal than “The Hawk.” The operative word here is “consistently.”

His frightening and career-altering KO of Herol Graham in 1990 triggered this vivid description by Robert Portis in The Fight City: “One of the most brutal and awe-inspiring one-punch knockouts ever witnessed won lead-fisted Jackson his second divisional title and further cemented his reputation as an all-time great puncher. The favoured Graham had dominated the first three rounds to such an extent that Jackson’s eyes were swelling shut and after the third round the ringside doctor informed “The Hawk” that he would soon have no choice but to stop the fight. The one-sided boxing lesson continued in round four before Jackson suddenly struck with a vicious right hook that instantly knocked Graham out cold.”

Graham recalled the incident in a conversation with Tom Gray of The Ring: “I made the mistake of going for a sucker punch, when he was in the corner, and Jackson responded with a knockout punch. I had to go to the hospital and there were some scary moments because I couldn’t remember a thing about the fight. Three or four hours later it all came back to me and that was a really powerful right hand shot….”

The Virgin Islander was 29-0 when another banger, Mike McCallum (26-0), stopped him somewhat controversially in 1986.

The Hawk added other unforgettable KO’s against the likes of Terry Norris, Buster Drayton, In Chul Baek, Ismael Negron ,Thomas Tate, Wayne Powell, and Dennis Milton. Many were unconscious before they hit the canvas. In particular, his KOs of Norris, Powell, and Drayton showed his signature raw power in a most frightening manner.

As one observer said, “The amount of speed, torque, and power generated in close quarters was unbelievable. He could knock out someone in a phone booth.”

Jackson ended his career in 1998 with a record of 55-6-0. Forty-nine of his wins came by way of KO and all 6 losses came the same way. Two of those losses came against perhaps the most concussive puncher of them all, Gerald McClellan. Heck, if Jackson was arguably the most lethal, then what of the guy who iced him twice?

The G-Man

Trained early in his career by Manny Steward, McClellan’s signature was the quick victory; a malevolent, torque-fueled knockout. In fact, only two of his first 29 fights went beyond the third round–and 20 of his final career victories were in the first round. He won the vacant WBO middleweight title by knocking out still another KO artist, John Mugabi, in one round in 1991.

(The previous year, McClellan was extended the distance in 8-round fights by Sanderline Williams and Charles Hollis. Williams possessed one of the best chins in boxing. The Hollis fight was an anomaly that simply defied logic.)

Going up against Gerald was like facing a Gatling Gun. Left hooks, right hooks, combos, straight shots and brutal bodywork, all off a stiff jab. Many of his opponents ended up like the Hawk’s—unconscious before they hit the mat. Truth be told, the two were more alike than different.

In August 1993, McClellan and Jackson fought on a star-studded show in Bayamon, Puerto Rico. Both knocked out their opponent in the first round. McClellan stopped his man, Jay Bell, in 20 seconds of the opening round with a vicious body shot. As Bell lay on the canvas, writhing in agony, the crowd looked on in disbelief. McClellan was defending the WBC version of the title that he won from Jackson. It was the quickest KO in middleweight championship history.

This fight with Bell came between McClellan’s two knockouts of Jackson. The first was a spectacular KO which was named the 1993 “Knockout of the Year” and the second (May 1994) was the result of a savage body shot in the first round in what would prove to be McClellan’s penultimate fight.

Now then, The Hawk simply cannot be considered the ultimate KO artist if he was twice KO’d by the G-Man, but one thing is certain: both had ferocious punching power. Julian Jackson was a worthy inductee into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and Gerald McClellan belongs there too.

Postscript: Obviously, more could have been written about Gerald’s subsequent boxing career, but this writer prefers not to do it. Dwelling on that tragedy has been done by better writers than me. Suffice to say, I remain a friend with the McClellan family.

Ted Sares can be reached at tedsares@roadrunner.com

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival