Featured Articles

The Roles Have Changed for Caleb Plant Who Isn’t Intimidated by Canelo Alvarez

The Roles Have Changed for Caleb Plant Who Isn’t Intimidated by Canelo Alvarez

It seems highly unlikely, almost impossible even, for anyone to see certain parallels between Canelo Alvarez, widely considered to be the finest pound-for-pound boxer in the world, and Mike Lee, described by one veteran observer as a “glorified club fighter” who rose faster and higher than his skill level suggested because of an unusual background that for a time made him something of a media darling.

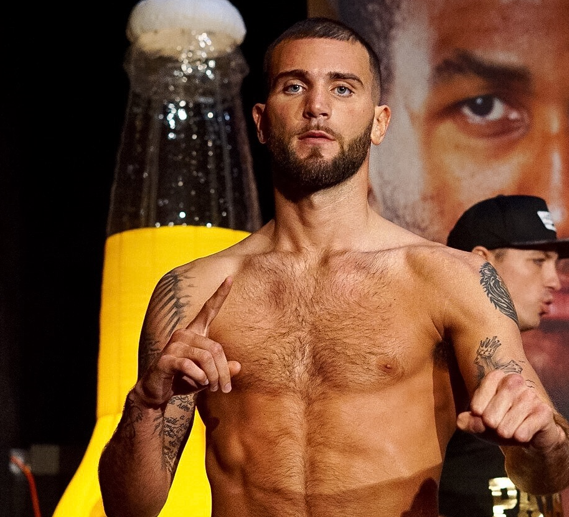

Not that he has said it in so many words, but it does seem possible that Caleb “Sweet Hands” Plant (21-0, 12KOs), who takes on the heavily favored Alvarez (56-1-2, 38 KOs) for the undisputed super middleweight championship of the world Saturday night at Las Vegas’ MGM Grand, and who brutally dismissed Lee in an IBF title bout nearly 28 months ago, will draw from the same motivational bubbling well of dislike to achieve the desired result. The only difference is that this time, it is Plant who will be cast in the role of would-be usurper Lee. In some people’s eyes, anyway.

Alvarez’s WBC, WBO, WBA (super) 168-pound belts will be on the line in the PBC on Showtime Pay Per View telecast, as well as Plant’s IBF strap.

Plant, a 29-year-old native of the small town of Ashland, Tenn., who now resides in Las Vegas, considers himself the best super middleweight fighter on the planet, but it is an assertion that can’t and won’t be verified until the 10-to-1 longshot does what no one other than the great Floyd Mayweather Jr. has been able to do, which is to hang a defeat on the hugely popular Mexican national hero. Becoming the first man to hold all four belts in his weight class from the most widely recognized sanctioning bodies should be ample enough reason for both parties to put forth their best effort on fight night, but Plant, not surprisingly, had been nursing a spark of resentment that he has since fanned into a raging bonfire.

It began when negotiations to stage the fight on its originally proposed date, Sept. 18, broke down over contractual issues. Alvarez then seemed set on arranging a fight with WBA (super) light heavyweight champ Dmitry Bivol, but that, too, was scrapped and the Alvarez camp circled back toward Plant. But while an accord was finally reached, hard feelings on both sides had intensified, with Plant and his support crew accusing Canelo and his handlers of not only being difficult at the bargaining table, but of downplaying a history of cheating, a reference to Alvarez having served a six-month suspension in 2018 for testing positive for clenbuterol, a banned substance.

Of the protracted wrangling, Plant said, “We tried to sit down with them. They told me what I would get paid, the opportunity that I had in front of me and I said, `Yeah.’ There wasn’t much haggle room on my end. The opportunity was presented to me, I took it, I wanted it. But they came back asking for even more. I can’t speak for their side for why things fell apart, but it had nothing to do with me. My side had been signed for weeks. When it fell apart, I just tried to be focused on the only thing that I could be in control of, which is making sure I was staying in the gym and doing what I was supposed to be doing. That way, if they came back around or not, I’d still be ready to fight whomever.”

And the charge of being a PEDs abuser Plant leveled at Canelo?

“I haven’t made any false allegations,” Plant said. “Everything I’ve said is factual. Whether he likes it or not, the facts are the facts. Maybe that’s what’s gotten under his skin, because he knows it’s true.”

The potential for some sort of premature skirmish was realized at a Sept. 21 press conference when Alvarez and Plan got nose-to-nose for the obligatory photo-op staredown, which resulted in a brief scuffle which Alvarez initiated with a hard shove to Plant’s chest. Plant came away with a cut below his right eye.

“This is new for me,” Canelo, who in most instances pays at least complimentary lip service to the guy he is about to fight, said later. “I’ve never had as much bad blood with an opponent as this one. Yes, this is the most animosity that I’ve had heading into a big prizefight.”

Ring announcer Jimmy Lennon Jr., who had an up-close-and-personal view of what went down, told me “It does seem that things can get out of hand more now at press conferences and weigh-ins. Staredowns, even intense ones, don’t have to lead to physical confrontations. I’m always pleased when the fighters shake hands and hug after the photos are taken. Boxing is a sport and you’re not supposed to let your focus or emotions out of control then.

“There’s so much of this now. And let’s be honest; it does sell tickets if something outlandish takes place. With Canelo and Plant, ticket sales definitely went up after that happened. But I don’t feel that was forced or staged. There was a lot of tension going on then, words were exchanged and it just got out of hand. So, yeah, it sure felt real.”

Not that the lead-up to Plant-Lee prior to their July 20, 2019, bout, the first defense of the IBF belt Plant had won on a 12-round unanimous decision over Venezuela’s Jose Uzcategui six months earlier, was any less confrontational on the part of the obviously miffed champion. To Plant’s way of thinking, Lee was a manufactured contender who, after logging 21 victorious bouts as a light heavyweight against middling opposition, was awarded a title shot in his first pro outing as a super middle because he was portrayed as unique because of factors that had little or nothing to do with the difficult road trod by most up-by-their-bootstraps fighters. An all-conference linebacker at his parochial high school, Lee began his college career at the University of Missouri before transferring to Notre Dame as a sophomore. While there, he won three consecutive Bengal Bouts intramural championships in addition to graduating with a 3.8 grade-point average in business. He reportedly had job offers from Wall Street which he put on hold to try his hand at boxing, in which he must have seemed like a wayward adventurer temporarily traipsing through a rough trade largely populated by rough customers like Plant.

The media, of course, was quickly drawn to the improbable tale of the personable, well-educated son of privilege who had spent part of his senior year at Notre Dame in Bangladesh, where he taught English and mathematics in addition to raising more than $100,000 that went toward the building of schools and health-care facilities in the Third-World country.

If anything could transform Lee into a prepackaged star upon his return to the U.S., it was the always-whirling Top Rank hype machine. After signing with TR founder Bob Arum, Lee compiled an 11-0 record before his contract expired, but even then he continued to remain firmly in the public eye as the result of his being one of several sports-world endorsers of the Subway sandwich-shop chain, a group that then included, among others, NFL stars Michael Strahan, Ndamukong Suh and fellow Notre Dame alum Justin Tuck, Olympic swimming gold medalist Michael Stewart, baseball slugger Ryan Howard, NBA standout Tony Parker and NASCAR driver Tony Stewart. He even was featured in a Subway ad that was seen by tens of millions of television viewers during Super Bowl Sunday in 2013.

In comparison to Subway’s other lineup of star pitchmen, Lee, who to that point had accomplished little of note, must have seemed famous mostly for being famous. In short order grumblers, Plant among them, intimidated that Lee had come onto the scene from Notre Dame’s Golden Dome with a silver spoon of caviar stuck in his mouth. The prevailing opinion was that boxing was his hobby, not his vocation, and he would step away from it whenever he decided it finally was time for him to take advantage of his degree, put on expensively tailored suits and head to work every morning carrying an expensive leather briefcase rather than a gym bag.

For his part, Lee tried to depict himself as much the same as other fighters. Yeah, his family had become well-off in monetary terms, but it had not always been so. And he said his paved and seemingly obstacle-free path to success had been marked by years of debilitating pain. His progress in boxing, he noted, was dramatically slowed when he began suffering constant back and joint pain. Eventually he was diagnosed with an auto-immune disease known as ankylosing spondylitis.

“I was told that I would never box again,” Lee said. “That really infuriated me because every time someone tells me I can’t do something, I want to do it twice. Doctors are smart and know what they are doing. I knew, though, that they didn’t know what I had in my heart and I was a different human being. I told them they were wrong, and I would figure it out and get back in the ring.”

Eighteen months later, in April 2014, Lee stopped Peter Lewis in six rounds, the start of a 10-fight win streak that got him his shot at Plant.

At the final prefight press conference, Plant listened to Lee’s tales of being an everyman who had had endured much in pursuing his boxing dream, and then it was the champion’s turn to speak. He immediately made it clear that he was not impressed by anything he had heard. Plant was dedicating the Lee fight to the memory of his late daughter, Alia, who died at 19 months old of an unknown illness which caused seizures, as well as to his mother, Beth Plant, who was shot and killed by a police officer for allegedly brandishing a knife in March 2019. Basically, he was saying, `OK, you just put your headaches and various aches and pain into the pot, so now I’m raising you two deaths in my immediate family.’

“You may have a financial degree, but in boxing I have a Ph.D.,” Plant, addressing Lee, said at the final press conference. “And that’s something you don’t know anything about.

“I’ve been doing this for 18 years straight – no breaks, no distractions and no Plan B. I commend you for doing this, but there’s no college degree for me. No high school sports, no acting gigs, no Subway commercials. Just boxing day in, day out, rain, sleet or snow.”

The fight, what there was of it, went as most had expected. Plant floored the overmatched Lee three times officially (four if you include another trip to the canvas perhaps incorrectly ruled a slip by referee Robert Byrd), the last knockdown convincing Byrd there was no need to proceed further. The end came after an elapsed time of one minute, 29 seconds into round three.

Mike Lee has not fought since.

So now Caleb Plant, the honest workman, is back at the same old stand, except that the guy in the other corner on Saturday night is so much more like him than Lee had been. Canelo Alvarez, now 31, turned pro at 15 and also came up the hard way, beating grown men with boundless talent and determination. Maybe he wasn’t always this dominant, but he had the potential to be so, and he would someday fulfill his destiny because boxing is not and never has been a hobby for him. He is who and what he is because he took his considerable skills and honed them to a razor’s edge, which he is again intent on displaying against someone with a like mindset.

“The media’s job is to make (Canelo) seem unbeatable,” Plant said. “That’s what they’re doing. But anyone who knows boxing and has seen him in with some of these high-level fighters – I’m talking about Triple G (Gennadiy Golovikin), I’m talking about (Erislandy) Lara, even Austin Trout – know he was beatable in those fights. There are things those guys were able to capitalize on, and I feel I possess a lot of those same skills, except I’m a full-fledged super middleweight. I’m not a 154-pounder, I’m not a middleweight. I’ve been fighting at this weight for a really long time. There are things I feel like – I know – I can capitalize on. On Nov. 6, that’s what I plan on doing.”

Asked for his final thoughts on Mike Lee, Plant said it’s not enough to have the benefit of good publicity. No spin doctor can help anyone inside the ropes, where truth is always there to be seen for what it is. “Not only was the media building him up, he was building himself up,” Plant opined. “I wanted to show him he wasn’t the real deal, that I’m the real deal. But that’s not just for him; it goes for any fighter that gets in there with me. I feel that way against anybody that’s in front of me. When the bell rings, all the talk stops. Who’s going to impose his will on the other man?

“I plan on imposing my will on Canelo and becoming the undisputed super middleweight champion.”

Editor’s Note: Bernard Fernandez, named to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in the Observer category with the class of 2020, was the recipient of numerous awards for writing excellence during his 28-year career as a sportswriter for the Philadelphia Daily News. Fernandez’s first book, “Championship Rounds,” a compendium of previously published material, was released in May of last year. The sequel, “Championship Rounds, Vol. 2,” with a foreword by Jim Lampley, arrives this fall. The book, published in paperback, can be ordered through Amazon.com and other book-selling websites and outlets.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 days ago

Book Review2 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds