Featured Articles

Joe Cortez Mourns the Loss of Gaspar Ortega, His Friend of 60-plus Years

“Gaspar Ortega has fought everybody who was anybody in the welterweight division since he turned professional in 1953. He’s been on television more times than Ben Casey and he’s had more fights than most pugs have had workouts. What he doesn’t know about boxing hasn’t been invented.”

So wrote Ron Amos in the May 14, 1964 issue of the Las Vegas Review Journal in reference to Ortega’s forthcoming fight at the Castaways, a little hotel-casino that sat next to a gas station in the center of the Las Vegas Strip. This would be Ortega’s only appearance in Nevada, but the vagabond prizefighter, a self-described boxing gypsy, sure did get around. He fought all over the U.S. and made three trips overseas during a career in which he had 176 documented fights and likely a few dozen more that weren’t recorded. His record, per boxrec.com, was 131-39-6 with 69 KOs.

Ortega passed away at age 86 on Dec. 13 in Naples, Florida, where he had had gone to live with a daughter following the death of his wife Iraida who passed away in November of last year. Gaspar and Iraida, a native New Yorker, were married for 64 years.

Born in Mexicali, Gaspar Ortega spent his formative years in Tijuana where lore has it that the home he shared with his parents and 11 siblings had no electricity and a dirt floor. He had his first twenty-three documented fights in northern Mexico and his twenty-fourth at Madison Square Garden where he gradually built himself into a headliner.

Ortega developed rivalries with most of the top welterweights of his day including the tough Cubans Isaac Logart and Florentino Fernandez. He won two out of three from future Hall of Famer Tony DeMarco, a trilogy shoe-horned into only 68 days. “After a fight,” Ortega recalled, “my manager would say, ‘Stay in shape. We might need you to fight again tomorrow.’ I would say, ‘I’m ready.’”

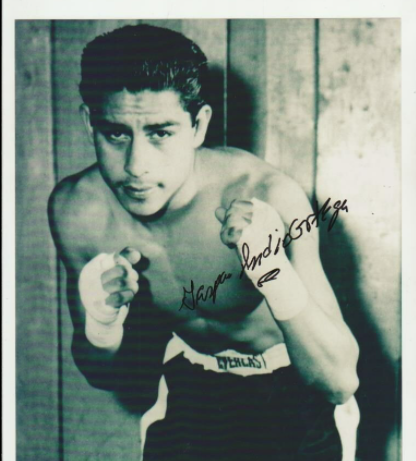

Ortega’s father was of Spanish descent and his mother was a Zapotec Indian. The elaborate Indian headdress that he wore into the ring was ostensibly meant to honor her although one suspects that the idea of it may have been conceived by a wily press agent. It made him one of the most well-known ring personalities in a day when there were two and sometimes three nationally televised fights every week. Indeed, he may have been the most well-known boxer of his era that never held a world title.

Ortega had one crack at it. On June 3, 1961, in his eighty-second documented bout, he challenged Emile Griffith at LA’s fabled Olympic Auditorium. They had met once before with Griffith winning a split decision, but on this particular night Griffith had all the best of it until the referee called it off in the 12th round.

Incredibly, Ortega wouldn’t be stopped again until very late in his career when he was stopped by junior middleweight champion Sandro Mazzinghi in a non-title bout in Rome. Ortega’s corner pulled him out at the conclusion of the sixth round. And that may be the most remarkable fact about Gaspar Ortega’s boxing career – that not once in 176 documented fights was “El Indio” ever knocked down for the count.

When Ortega moved to New York, he took up residence in an apartment building in a complex of six-story buildings on East 99th Street which was a few subway stops away from Stillman’s Gym where he trained under the watchful eye of the noted trainer and cut man Freddie Brown. Joe Cortez and his brother Mike lived with their divorced mother and two siblings in the building right next door.

Mike, a year older than Joe, was thirteen years old when Ortega became his neighbor. According to an article in the New York Daily News, Mike took to following Ortega around when the boxer did his roadwork and mimicked Ortega’s shadow boxing. That served him well when he took up the sport at the boys’ club on 111th Street.

Joe followed his brother into the squared circle and both became stars on the regional amateur circuit. The Cortez brothers won back-to-back New York Golden Gloves titles in 1960 and 1961, Mike at 126 and then 135 pounds, Joe at 112 and 118. (The 1961 finals at Madison Square Garden attracted a crowd of 16,119, indicative of the role that amateur boxing played back then in the sporting life of the city.)

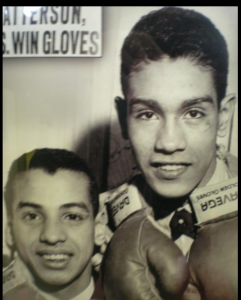

Joe (l) and Mike

As a pro, Mike Cortez never went far, finishing 16-10-2. Joe fared better, 18-1 (13-1 documented), but never advanced beyond the preliminary stage. His final fight was at the La Concha Resort in San Juan, not far from Fajardo, Puerto Rico, where Joe worked as an assistant manager at the Conquistador Hotel after starting as a front desk clerk.

Although they weren’t that far apart in age, Ortega was something of a surrogate father to the Cortez brothers. He mentored them and Joe returned the favor, mentoring Gaspar’s son Mike Ortega who, like Joe, would go on to become a world class referee. Joe Cortez is Mike Ortega’s godfather. (Although he grew up in New Haven, Connecticut, where his parents eventually settled, Mike Ortega was actually born at a hospital in Hollywood, California. Papa wasn’t there. Gaspar was at work at LA’s Pacific Coast League baseball park, Wrigley Field, carving out a split decision over Kid Gavilan.)

“I talked with [Gaspar] every month on the phone for the last 50 years,” Cortez told this reporter. “He was like family. I got him hired as an extra in the Rocky Balboa film and he stayed in our house during the six days they were filming here in Las Vegas.” In the 2006 movie, Cortez is the third man in the ring for the climactic fight scenes. Ortega is seen seated at a ringside table portraying a boxing commissioner.

Gaspar Ortega kept mentoring novice boxers almost to the end of his days. In Connecticut, he worked as a counselor for a nonprofit agency for troubled teenagers and volunteered his time as a boxing instructor at a community center. He didn’t leave the sport with a lot of money, but with enough to live comfortably. It was his habit to return to Tijuana for one or two weeks every year where, according to Iraida, he was welcomed like visiting royalty.

In documented fights, Ortega answered the bell for 1293 rounds. A boxer with this many rounds on his dossier figures to be walking on his heels with marbles in his mouth before he is old enough to draw social security, but “El Indio” was one of the lucky ones, blessed with a cast-iron constitution. More amazing, for many years he was a pack-a-day cigarette smoker.

Joe Cortez, who was enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2011, has had some tough times in recent years. In 2009, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer (it’s in remission). His wife Sylvia is a two-time breast cancer survivor. Their daughter Cindy has been in a wheelchair since 1996, the result of a rollover accident caused by a defective tire that left her a qudriplegic. And in November of last year Joe came down with Covid which resulted in a five-month hospital stay during which he wasn’t allowed to have any visitors.

“I weathered the storms,” says Cortez, 77, proudly. But the hits keep coming, even if they don’t directly impact his immediate family. For Joe Cortez, losing Gaspar Ortega was like losing a brother.

Check out more boxing news on video at the Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Shafting of Blair “The Flair” Cobbs, a Familiar Thread in the Cruelest Sport

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden