Featured Articles

Remembering **World Heavyweight Champion** Lee Savold

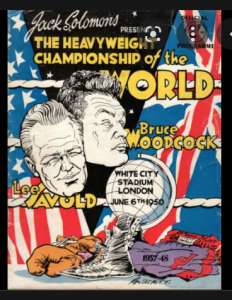

On June 7, 1950, Lee Savold defeated Bruce Woodcock before 50,000 at London’s White City Stadium. Savold had all the best of it before Woodcock’s corner pulled him out after four rounds with a badly cut eye.

For Savold, this was the culmination of a long and checkered career. Born on a farm in northwestern Minnesota – Sioux Indian territory – the tenacious leather-pusher of Norwegian stock had paid his dues. With the victory, Savold became the world heavyweight champion in the eyes of a certain segment of the boxing universe.

A little background: On March of the previous year, Joe Louis announced his retirement. Louis had reigned as the world heavyweight champion for nearly 12 years during which he had made 25 successful title defenses. His leave-taking unleashed a battle over control of the abdicated throne and the huge profits that would accrue to the promotional group that won the scrum.

The newly-formed International Boxing Club, of which Joe Louis was ostensibly a partner, had the blessing of the National Boxing Association when it decreed that Jersey Joe Walcott and Ezzard Charles would fight for the vacant title. This wasn’t an attractive pairing. Jersey Joe had lost 15 of his 58 pro fights and was considered past his prime. Ezzard Charles was a solid technician but he was colorless and he wasn’t a full-fledged heavyweight. He had never entered the ring carrying more than 180 pounds.

This edict didn’t go over well in Great Britain where boxing was enjoying a post-war boom. The poohbahs at the British Boxing Board of Control felt snubbed. Undoubtedly at the urging of London promoter Jack Solomons, Mr. Big in British boxing, they decided to recognize the winner of the forthcoming match between Bruce Woodcock and Savold as the world heavyweight champion. The European Boxing Union sided with them.

Lee Savold’s Herky-Jerky Climb Up the Ladder

Lee Savold was 18 years old when he made his pro debut at a county fair in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. For the next-two-half years he plied the Upper Midwest circuit. His most notable match during this period was a bout in Minneapolis with Jack Gibbons. The son of Mike Gibbons and nephew of Tommy Gibbons – both of whom would be elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame – Jack Gibbons was too slick for Savold and won the decision.

This was a rare 10-rounder for Savold. The loss knocked him back to the preliminary ranks.

In February of 1936, with his career going nowhere, Savold went west. He had his next 16 fights in California where he supplemented his ring earnings as a stevedore. Things went well at first, but then turned sour. He was 9-7 in California rings bringing his overall record to 34-23-2.

Savold returned to his home state and took a job as a bartender in Minneapolis. He was out of the ring for 14 months during which his weight reportedly ballooned to 260 pounds.

Savold was lured back to the ring by Pinkie George, the leading boxing and wrestling promoter in Iowa. Savold had appeared on three cards in Iowa when he was just starting out and flashed enough potential that Pinkie remembered him. He induced Savold to re-settle in Des Moines, put him on a strict regimen that shed pounds and built muscle, and dressed him with a nickname: The Battling Bartender.

Savold, who stood six-foot-one, was a svelte 184 pounds when he returned to the ring on July 7, 1938 at Riverview Park in Sioux City, Iowa. Under Pinkie George’s management, Savold won 14 of 18 matches preceding his Dec. 4, 1939 engagement in Des Moines with Maurice Strickland.

A New Zealander, Strickland was well-touted and folks inside the boxing community took note when Savold knocked him out in the third round.

Strickland’s U.S. representative was “Honest” Bill Daly whose home base was in Englewood, New Jersey.

In boxing, “honest” is a pejorative. As the late, great LA Times wag Jim Murray noted, Daly was honest in the sense that he never stole an elephant or a battleship. But with an assist from Savold’s Iowa trainer Hymie Wiseman, who was given a piece of the action, Honest Bill stole Lee Savold from Pinkie George. Savold went with the flow and moved his tack to the Garden State, taking up residence in Paterson.

With the well-connected Daly calling the shots, Savold procured bouts of international importance. The first of this description was 12-round, non-title fight with reigning light heavyweight champion Billy Conn on Nov. 24, 1940, at Madison Square Garden. The Pittsburgh Kid was too clever for the Battling Bartender and won a wide decision, but Savold broke Conn’s nose during the fight with a punch that Conn would remember as one of the hardest that he ever received.

The Conn fight was a good learning experience for Savold who won 18 of his next 20 fights. Both losses were inflicted by Harry Bobo, a good black boxer from Pittsburgh who never got his proper due.

Savold’s signature win during this run was an eighth-round stoppage of Lou Nova. This was Nova’s first fight since his failed effort at wresting the title from Joe Louis. Nova was no match for the Brown Bomber who stopped him in the sixth frame but he had some good wins on his ledger including two wins inside the distance over Max Baer and Savold would be the underdog when he met up with Nova on a Monday night at Griffith Stadium in Washington DC.

Savold cut Nova to pieces and the referee stopped the fight after seven frames when the gash over Nova’s left eye worsened. The match aired on the Mutual Radio Network which had more than 200 affiliates. The following year, Savold defeated Nova in a more dramatic fashion, knocking him out in the second round at Chicago’s Wrigley Field.

Between these two fights, Savold was his usual erratic self. He split two fights with Tony Musto and came out on the short end of 10-round bouts with Tami Mauriello and Jimmy Bivins. After defeating Nova for the second time, he became even more inconsistent. Mauriello beat him again, he lost two out of three to rugged Joe Baksi, was twice out-pointed by journeyman Phil Muscato, and was knocked out in the second round by fearsome Elmer “Violent” Ray.

Savold’s career was going nowhere again when he accepted a match with Gino Buonvino. Savold took the assignment on 48 hours notice, subbing for Baksi, a late scratch with an ankle injury.

Recognized as the heavyweight champion of Italy, Buonvino was unbeaten in his last 11 starts. In a shocker, Savold knocked him out in 54 seconds, the fastest knockout on record for a main event at Madison Square Garden.

The knockout of Buonvino coupled with two more wins over lesser foes boosted Savold to #3 behind Ezzard Charles and Jersey Joe Walcott in The Ring magazine ratings. That said more about Honest Bill Daly’s negotiation skills than about Savold’s true ability. He maintained that placement after he went to London and lost by disqualification to Bruce Woodcock in what would be the first of their two meetings.

Bruce Woodcock

The son of a former British Army lightweight champion, Bruce Woodcock, born and raised in Doncaster, was nothing special but you couldn’t tell that to the Brits who fervently embraced him after he won the British and British Empire heavyweight titles with a sixth-round knockout of Jack London in 1945. In his most recent bout, he had scored a fourth-round stoppage over American veteran Lee Oma who was felled by a punch that didn’t look especially hard. Spectators tossed pennies into the ring as they did whenever a fight ended suspiciously.

Savold-Woodcock I, contested on Dec. 6, 1948 before a capacity crowd of 10,700 at London’s Haringay Arena, also ended suspiciously. Savold was disqualified in the fourth round for hitting Woodcock below the belt. The crowd booed as Woodcock lay on the canvas, writhing in agony. It struck many that he was play-acting. “Savold lost the fight but showed himself to be the better man,” said the correspondent for the Associated Press.

Woodcock, who had lost only twice in 35 starts, regained his lost prestige with a third-round stoppage of South African heavyweight champion Johnny Ralph in Johannesburg and a beat-down of popular Freddie Mills, conqueror of light heavyweight champion Gus Lesnevich, in London. Mills was on the deck five times before he was counted out in the 14th round.

When the folks at the BBBofC decided that they would not kowtow to American interests in naming a successor to Joe Louis, which ruled out Ezzard Charles and Jersey Joe Walcott, Woodcock and the highly-rated Savold were the logical picks to fight for the vacant title. It helped that promoter Solomons had doctored the film of the first fight. It showed the Englishman out-punching Savold over the first three rounds when the opposite was true.

The blue-collar amusement of greyhound racing was then flourishing in London and Savold-Woodcock II was planted at White City, London’s premier dog racing facility. The stadium was configured to hold 50,000 for the fight, the maximum allowed by the authorities for reasons of traffic control. It would be written that all 50,000 tickets were sold before the ink was dry on them.

Originally set for Sept. 6, 1949, the fight was pushed back 10 months when Woodcock suffered a shoulder injury in an automobile accident; he wrapped his lorry around a tree.

When the fight finally came to fruition, the action in the ring was somewhat similar to the first meeting, only a lot bloodier. When Woodcock’s corner pulled him out after four frames, he was bleeding from his nose and his mouth and had a two-inch gash over his left eye that “spurted blood like a fountain.”

Woodcock caught Savold flush with a number of right hooks but they had no effect; Savold kept moving forward. The American invader, said the ringside reporter for the Nottingham Evening Post, was a “cold, cruel and calculating fighting machine.”

Savold had only two more fights before calling it quits. On June 15, 1951, he met Joe Louis at Madison Square Garden in a fight that was forced out of the Polo Grounds by bad weather. Beset by tax problems, the Brown Bomber had returned to the ring after a 27-month hiatus.

On this night, Savold’s opponent was the cold, cruel, and calculating fighting machine. Louis carved him up before ending matters in round six with a series of punches climaxed by a short, left hook to the jaw that knocked Savold off his pins. He struggled to get upright but wasn’t able to beat the count.

Across the pond, this made Joe Louis the world heavyweight champion once again. It mattered not that Louis had been widely out-pointed by Ezzard Charles in his first comeback fight.

Eight months later, Savold met Rocky Marciano in a 10-rounder at Philadelphia’s Convention Hall. This was a terrible fight. Marciano’s punches were mostly wild but Savold offered little in return and his torso was smeared with blood when his corner pulled him out after six rounds. In an odd comparison, the great sportswriter Red Smith likened Savold’s poor showing to that of a man with a bellyache carrying an armful of packages across Times Square during rush hour.

And so, this is how it ended for Lee Savold, a shell of his former self and his former self was never that great to begin with. His final record, per boxrec, was 98 wins, 41 losses and three draws. He scored 72 knockouts and was stopped 12 times. But for 13 months he reigned as the heavyweight champion of the world in merry old England, the cradle of pugilism, heady stuff for a farm boy from Minnesota who was once a hog-fat bartender.

Having answered the bell for 814 rounds, Savold was a prime candidate for pugilistic dementia but he beat the transmutation to the punch as it were. In April of 1972, he suffered a stroke and died a month later at a rehab hospital in Neptune, New Jersey. He was 58 years old.

—

Postscript: The BBBofC never did recognize Ezzard Charles or Jersey Joe Walcott who took turns beating each other in 1951. The title became vacant yet again that year in the eyes of British interests when Louis was knocked out by up-and-comer Rocky Marciano and it remained vacant until Rocky made things whole again. With no viable alternative, the Brits acknowledged the Rock as the true champion after he toppled Walcott on Sept. 23, 1952, felling Jersey Joe, who was ahead on the cards, with a pulverizing punch that would have felled a horse.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Arne K. Lang’s latest book, titled “George Dixon, Terry McGovern and the Culture of Boxing in America, 1890-1910,” will shortly roll off the press. The book, published by McFarland, can be pre-ordered directly from the publisher (https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/clashof-the-little-giants) or via Amazon.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review3 days ago

Book Review3 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds