Book Review

Christy Martin: Fighting for Survival / Book Review by Thomas Hauser

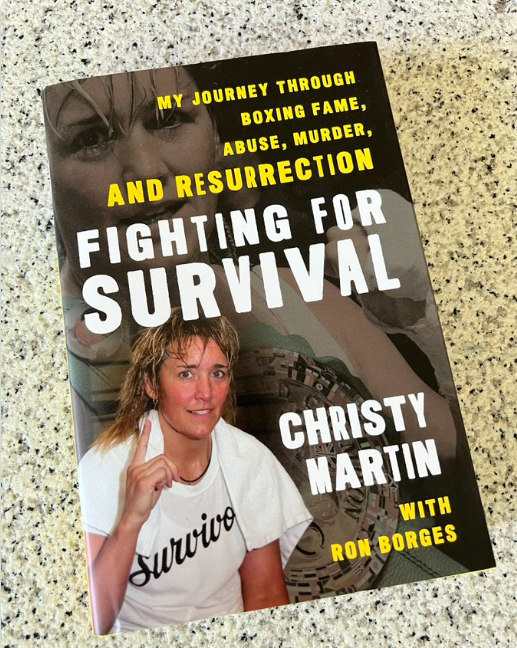

More than any other fighter, Christy Martin was responsible for legitimizing women’s boxing in the public eye. She was also a closeted gay woman married to a man who physically and psychologically abused her for years before stabbing her multiple times, shooting her in the chest, and leaving her for dead on their bedroom floor. Fighting for Survival, written with Ron Borges and published by Rowman & Littlefield, is her story.

Martin was born in Mullen, West Virginia, on June 12, 1968, and grew up in the coal-mining town of Itmann. Her father was a miner. “All you need to know to understand the limits of Itmann,” Martin writes, “is your cellphone won’t work there.”

When Christy Salters (her name before she was married) was six, she was sexually molested in the basement of her parents’ home by a 15-year-old cousin who forced her to perform oral sex on him. Other than her future husband, she didn’t tell anyone about it for 37 years.

She was a troubled adolescent. “I started associating drinking with popularity,” she acknowledges. “I was running around with thirty-year-olds when I was still a teenager. I sold speed to friends of my parents. I was a bad kid doing things I shouldn’t have done.”

She was also gay.

Christy had sex with a girl for the first time when she was thirteen. In high school, she ventured back and forth between the sexes.

“I wasn’t together at the time when it came to totally understanding my own sexuality,” Christy acknowledges. “Can I be straight if I try? Should I be who I am or try harder to please everyone else? You doubt sometimes the direction you’re going. Other times, you’re totally sure. I’d been with men and women in high school so I’d say I was bi-sexual at that time. But to me, being in a relationship with a woman was easier. It was always where I was most comfortable.”

In towns as small as Itmann and Mullens, people talk,” Christy continues. “I knew they wondered about me. It is exhausting hiding who you are from your family and your friends and the world around you. You’re always afraid someone knows the truth. You may tell yourself you don’t care. But if you really didn’t care, you wouldn’t be hiding what you’re doing or what you’re feeling, would you?”

Coming out wasn’t an option. Christy’s mother was vehemently homophobic, a view shared by many people in that corner of the world. “Put it this way,” Christy says. “You weren’t coming out in Itmann, West Virginia. Not unless you were planning on leaving the same day.”

Then, to further complicate matters, Christy got pregnant at age 21. Chris Caldwell had been her “sort of boyfriend” since they were in fifth grade. As the years passed, they saw each other from time to time.

“One night,” Christy remembers, “we went out as friends, had a few drinks, and had drunken sex. I was in love with Bridget [her girlfriend of the moment], so why did that happen? I was selfish, that’s why. There’s no other explanation. I never told my parents. I didn’t want the added pressure of them saying they’d raise the baby while I finished school, which I know my Mom would have done.”

So she chose to have an abortion.

“It’s one of those things that will always bother me,” Christy writes. “But it’s the decision I made. I still feel guilty about it. But I made a choice and I had to move forward.”

Meanwhile, Christy found a safe haven in sports. Despite being only 5-feet-4-inches tall, she excelled in basketball, averaging 27 points and six rebounds per game during her senior year of high school. In her junior and senior seasons, she was designated first team All-State.

“I had a pent-up rage inside about having to hide that I was gay from the world as I knew it,” she recalls. “You’re so angry that you can’t be who you want to be and you can’t change who you are. You’re trapped and it makes you mad without understanding what you’re really mad about. In sports, it’s acceptable to be overly aggressive so you can let some of those emotions out in a safe place. At times it even gets rewarded.”

That led to boxing.

“I’d been going to Toughman shows for years with my friends and family,” Christy reminisces, “and always wondered what I’d do if the bell rang and I found myself standing all alone in one corner of the ring.”

Then, at age nineteen, she saw a poster inviting women to participate in a “Mean Mountaineer” tournament.

“That,” Christy recalls, “is how, on October 1, 1987, I found myself standing in the wings at the Raleigh County Armory wearing a pair of 16-ounce boxing gloves and leather headgear, waiting to try something I knew nothing about.”

But Christy Salters had an advantage over the other women in the tournament. “Many of them were muscular,” she remembers. “They looked stronger than me. But I was in better condition and I was an athlete. Most of them were just tough girls.”

Christy won her first fight by decision and, the next night, came back for more. In the finals, she knocked out an opponent who was heavier and five inches taller with a single punch.

“She wasn’t staggering around and kind of woozy,” Christy recounts. “She was out and the crowd went into a frenzy! It was awesome. I could feel the adrenaline rush from the crowd, and that was it for me. I was hooked on boxing. The first thing I thought of when they gave me the champion’s jacket and the $300 [prize] was, ‘When’s the next one?'”

Soon, a boxing ring was one of the few places where Christy felt safe.

“I won’t sugarcoat what boxing is about,” she writes. “You don’t find too many well-adjusted prizefighters. We all have our demons, something driving us to run toward pain when human nature says run away. You don’t find many fighters who weren’t spawned out of some kind of dysfunction. If you’re normal, whatever that means, you’re not likely to choose a sport that involves getting hit in the face.”

But Christy continues, “I loved boxing more than anything in my life. The ring was where I could be me. In the ring, who I chose to love didn’t matter. I felt able to get out my frustrations and the anger that was locked up inside me. It was okay for me to go in there and be as aggressive as hell and as competitive as I wanted to be. They might laugh at us on the way into the ring. But if we fought hard and did some damage, they’d cheer us on the way out. They didn’t care if you were gay or straight. Whatever it was that drove you to fight was fine to the people watching as long as you could fight. I just wanted to be a boxer. It became all that mattered to me. For too long, I didn’t have control of anything but the 20-by-20-foot area inside those ropes. Maybe that’s why I loved it in there so much.”

On September 9, 1989, at age 21, Christy turned pro. “Women’s boxing was not yet a truly legitimate sport,” she acknowledges. “It was still a freak show, but at the time I didn’t give it a thought. I just wanted to fight.”

Soon after, her promoter suggested that a man named Jim Martin become Christy’s trainer. On March 20, 1992, Christy Salters and Jim Martin were joined together as husband and wife. Much more on that later.

By the end of 1993, Martin had 19 wins as a pro against a single loss and one draw. Then she was brought to the attention of Don King who signed her to a contract calling for five six-round fights a year at $5,000 a fight. Prior to that, she’d been making roughly $500 per fight and her biggest purse had been $1,200.

Christy’s inaugural fight with King was a first-round knockout of Susie Melton on January 29, 1994. Five more victories followed. Then, on December 16, 1995, King matched her against a sacrificial lamb named Erica Schmidlin who was making her pro debut. As expected, Martin won on a first-round knockout. That night marked a turning point because Christy’s bout was on the undercard of Mike Tyson vs. Buster Mathis Jr.

Martin fought on Tyson undercards six times. Those fights, she says, “were my stepping stones to a world I never knew existed – the big-time side of boxing.” Tyson, she writes, was “like a magic carpet ride for me, providing a platform to show my skills and a huge audience that turned me into someone I never thought I could be.”

After destroying Schmidlin, Martin defeated a no-hope opponent named Melinda Robinson and Sue Chase (who would end her career with a 1-23-1 record). The Chase fight was significant because it was on the undercard of Felix Trinidad vs. Rodney Moore at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas and was televised by Showtime – the first time that a fight between women boxers aired nationally in the United States. That was followed by a first-round knockout against another no-hoper named Del Pettis.

Then, three weeks later, everything changed. On March 16, 1996, Christy was matched against an Irish boxer named Deirdre Gogarty on the undercard of the rematch between Mike Tyson and Frank Bruno on Showtime-PPV.

Christy was a natural 135-pounder. Two hours before the weigh-in, Gogarty (who would finish her career with 8 wins in 13 fights) weighed 124. After stuffing rolls of quarters into her bra, socks, and underwear, Deirdre tipped the scales at 130.

A 60-53, 60-53, 59-54 beatdown followed. But Martin was about to become famous, not because she won but because Gogarty broke Christy’s nose. It gushed blood throughout the fight. Writing for the Associated Press, Ed Schuyler later called it “the most lucrative bloody nose in the history of boxing.”

“That fight,” Christy says, “turned in a matter of seconds from being an event that was being laughed at and ridiculed in the arena to one that absolutely thrilled people who were watching. That drippy nose and the uniqueness of the story of the husband-and-wife fighting team [by that time, Jim Martin was Christy’s husband] turned me into a national phenomenon.”

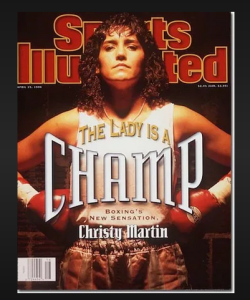

In the weeks that followed, Christy appeared on dozens of national television shows and was on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

“You could not get any bigger in the world I was inhabiting than to be on a Sports Illustrated cover,” she writes. “And there I was, staring back at myself from every newsstand in America. You dream about some things, but other things are so big you don’t even think about them happening because just the thought would be ridiculous. That’s what being on SI’s cover was for me.”

After beating Gogarty, Martin defeated Melinda Robinson for the second time followed by a first-round knockout of Bethany Payne. Then she signed a new contract with Don King calling for a minimum purse of $100,000 per fight. All told, she fought 27 times over the course of eight years with King as her promoter. Writing about a memorable moment in their relationship, she reveals, “Don did try to proposition me once in Venezuela at a WBA function. I asked him to go into another room because I needed to talk to him and he came on to me. After he made his pitch, I laughed and told him I only wanted to fight my way to the top. He started cackling and said, ‘You’re already at the top.’ Then he came to hug me and poured his drink down the back of my dress.”

After leaving King, Christy fought eleven times over the course of ten years. But the good part of her career was over. Her record in those eleven fights was 5 wins, 5 losses, and a draw. Age and a higher level of opponent had caught up to her.

The worst of the defeats was a fourth-round stoppage at the hands of Laila Ali in 2003. Laila was six inches taller than Christy and outweighed her on fight night by at least twenty pounds. Christy’s announced weight of 159 was as phony as Deirdre Gogarty’s had been seven years earlier. Why did she take the fight? For a $400,000 purse. And to use her word, she was “massacred.” The fight ended when she took a knee and chose not to rise before the count of ten.

Looking back on that night, Christy writes, “I was totally embarrassed and ashamed. I’ll never get over it. I’d be more accepting of losing to her if I’d been knocked out or took a beating for six more rounds. To quit on my knees is not who I was.”

Virtually all boxer autobiographies focus on a fighter’s ring career. This one does it better than most. But what separates Fighting for Survival from other fighter autobiographies is the horrifying nature of Christy’s life outside the ring coupled with the brutally honest way in which she recounts it.

When Ron Borges met with her to discuss the possibility of their working together, one of the first things he told her was, “I’m not interested in working on a dishonest book.”

Neither was Christy. Later, as she began opening up about the horrors of her life, Borges counseled, “You don’t have to tell me everything bad that happened.”

But she did.

“I’ve never dealt with anybody who was more open about her life than Christy Martin,” Borges says. “There were times when we had to stop because the memories overwhelmed her. I don’t think I could do what she did with me. But Christy really believes that she survived the murder attempt and everything that came before it as part of a larger plan. And her goal now is to reach as many victims of abuse as possible.”

Christy’s decision to marry Jim Martin (her trainer) was a watershed moment in her life. He was 24 years older than she was. Why did a gay woman marry a man old enough to be her father?

“I have to admit, I was intrigued by him and his boxing stories,” Christy writes. “Now that I’m free and looking back thirty years, it makes no sense. But when I remember the girl I was then, a naïve kid from Nowhere, West Virginia, I can understand what I did. I wasn’t attracted to him. I was never passionate about him. The night Jim Martin proposed to me, I was ill-prepared to do what would have been best. I wasn’t strong enough to declare to the world who I really was.”

“When we first got married,’ Christy continues, “I was still a little confused about my sexuality. Deep inside, I knew I was gay. I spent a lot of years trying to figure out how I felt about that. But the longer we were together and the better I understood who I really was, the more it weighed on me. So there I was; a closeted gay woman athlete in a sport that barely existed with a boyfriend older than my Dad. All my passion came out in the gym because there was none at home. We got along all right in those days because we had boxing in common and that was our main focus. I’d say, in those years we were married, I was really asexual. It got to the point where I didn’t care about sex at all. I wanted to be in love with someone but I replaced that desire with a love for boxing.”

Christy’s rise to stardom after the Gogarty bout threatened to upend the applecart.

“I was now a gay woman in a phony marriage suddenly under the microscope that is the American hype machine,” she recalls. “Thankfully, it was the American hype machine before social media. I have a lot of things to be thankful for. And the absence of things like Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and the like back then are some of them because, had they existed, I would have been ‘out-ed’ long before Jim put a bullet in my chest and destroyed my hiding place.”

Also, Christy reminds readers, “Part of the boxing sell for us was that I was a married woman, trained and managed by her loving husband, so how could I be gay?”

The deception came with a heavy price attached. Christy says that, without her knowledge, her husband skimmed large amounts of cash off the top of her fight purses. There were what she describes as “almost daily emotional beatdowns.” And at times, Jim was physically abusive. “But when the abuse is mostly emotional manipulation,” she explains, “you see it differently. You question what you can do to fix things. You start to think he’s right about you. You’re the problem. It often takes a long time before you realize who the victim really is. That’s the kind of emotional control someone can have over you. You know you should leave, but you’re ashamed of the situation you’re in and afraid of the consequences if you go.

“A lot of women end up in similar situations to the one I was in,” Christy continues. “We stay out of fear, out of obligation, out of believing it’s all we deserve. The brave ones don’t stay. But would an openly gay female get the same chances I got if I wasn’t hiding who I really was? I hadn’t seen anyone who did, and I wasn’t about to risk it all to find out. I was a lesbian locked in a sham marriage designed to protect me from a sporting world I’d come to believe would never accept me as I was. [So] you compromise. You lie. You hide. You try to fit into a world that isn’t your own creation. You accept things you never thought you’d accept. You replace boxing for love and try to equate financial success with personal happiness.”

It didn’t work.

Writing about her husband, Christy states, “Protecting his wife never factored into his thinking. I was just a human ATM machine to him. He kept telling me I’d become a star and make him a lot of money but until that happened we needed another way to supplement what the fights brought in. And Jim came up with quite a solution. He wanted me to fight men in their hotel rooms. He said he’d heard there were guys who got off on it and they’d pay me to beat them up. When he first suggested it, I hollered at him, ‘Bitch! Get a job!’ But it didn’t take him long to convince me to do it, like he did with so many things I wish had never happened.

“The first time was in a hotel room in Fort Lauderdale,” Christy remembers. “I’m in this guy’s room, ready to fight, and all he kept trying to do was grab me and hold while I beat the bejesus out of him. The guy seemed to like it. Go figure. When it was over, we took his money and left. I felt like a prostitute must feel the first time. I felt dirty. I knew that hadn’t been about boxing. It was a sex thing from the start for the guy. I said I’d never do it again. But of course, I did. When you need money and all you have to do is go punch some guy around in his hotel room, it’s easy to find an excuse to do it again. The second time, it was easier to accept. I still didn’t feel right about it but you find ways to justify it. I told myself, whatever it is for the guy, it’s just boxing to me. Every time I did something like that, I left a little piece of myself back in that room. A piece of my dignity had disappeared.”

Christy’s unhappiness and confusion caused her to cross over other lines of propriety as well. Prior to fighting Andrea DeShong, she labeled her opponent a “dyke bitch.”

“I said what I said,” Christy admits. “I should never have done it. But I did.” Making matters worse, she later told DeShong, “I’m going to put something on you that your girlfriend can’t get off.”

“It was another part of my self-destruction,” Christy acknowledges. “I paid a price for those kind of statements and still do to this day with some people in the gay community.”

She also got into a fistfight with a woman in a parking lot and wound up paying $30,000 to settle a lawsuit that arose from the incident.

Worse, she got hooked on cocaine.

“My whole life, I’d been against using drugs,” Christy writes. “I tried marijuana in high school but I didn’t like the high. Same with speed. Tried it. Didn’t like it. So I stuck with drinking to excess instead. But as my life and my career unraveled, so did my resolve. One night, Jim came home with a baggie and dropped it on the table in front of me. He said that a fighter announced he was done with cocaine and there was the proof. I took the bait. The bag sat there for a day or two, looking at me. I didn’t care about myself and I hated Jim and what my life had become. What did it matter if I tried cocaine just once? I was alone the night I finally grabbed that baggie and opened it. I snorted a line and it was like the first time I knocked someone out and the crowd went crazy. I loved the feeling it gave me. At first, I only did it on Friday nights and weekends. Pretty soon, it was Mondays too. Then it became every day. It took a month until it had me. Pretty quickly, I’d do anything for coke. Jim would do it occasionally with me but mostly it was me, alone in the house. I was also taking pain pills for all the injuries I’d had in boxing and drinking, too. I overdosed so many times I should be dead. Basically, if I was awake in those years, I was high.”

Christy was hooked on cocaine for more than three years. Then, through the muddle that her mind had become, she had an epiphany.

“I was walking through my house, high, when I saw my reflection in a mirror and stopped dead in my tracks. I thought, ‘You really look like an addict.’ At that moment it hit me. What was looking back at me wasn’t Christy Martin. It wasn’t the Coal Miner’s Daughter. It wasn’t the WBC world super-welterweight women’s champion. It was a drug addict. That’s what I’d become. I immediately went and did a line to try and erase that thought but it wasn’t the same. By the next day, I’d decided things needed to change and I had to be the one to make the change. That day, I realized if I bent over and did one more line of cocaine, I’d do it until I was dead.”

Then Christy told Jim that she was going to leave him.

“Five days later [on November 23, 2010],” she writes, “stone cold sober, I was lying on my bedroom floor with a bullet in my chest, stab wounds all over my body and blood everywhere. I was finally free, if I didn’t die first.”

Jim Martin was tried and convicted of attempted murder in the second degree and sentenced to a minimum of twenty-five years in prison. He won’t be eligible for release until 2035.

After recovering from the attempt on her life, Christy had two more fights and lost both of them. She also suffered a stroke while in the hospital undergoing surgery for a broken hand after the first of those two encounters.

“I stayed in ICU for a week,” she recalls. “When I finally left, I couldn’t walk right, talk right or see right. My words were slurred and I had double vision which remains a problem for me at times to this day.”

She needed a cane to get around. But she was allowed to fight again. “The California State Athletic Commission [which oversaw the bout] didn’t have a clue,” she notes.

But Fighting for Survival has a happy ending. Martin has steered clear of cocaine for more than a decade. And in 2017, she married Lisa Holewyne. Their marriage is unique in that, on November 17, 2001, they had fought each other at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas with Christy winning by decision.

“I was one hundred percent sure I wanted to spend the rest of my life with Lisa,” Christy writes. “And five years later, nothing has changed. I was surer of that than anything in my life, including my decision to give over my life to boxing. I still love boxing but it isn’t my first love anymore. Lisa is.”

Fighting for Survival is written the way Christy fought. Straightforward and don’t hold anything back. It goes beyond being a boxing book and is as honest as any autobiography I’ve read.

There’s an art to capturing another person’s voice, and Borges has it. One never gets the feeling that he’s putting words in Martin’s mouth. Rather, he’s helping her organize her thoughts and putting them on paper. There’s no need to over-sensationalize. The facts are lurid enough.

Christy is active today in working to combat domestic violence. She also promotes fights in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Florida. Summarizing her journey, she writes, “Let’s be clear about one thing. Trust and believe when I tell you, this is not a victim’s story. Although a lot of folks might see it that way, it is not a victim’s story at all. It’s a survivor’s story.” And she adds, “I’m not looking for a pity party for Christy Martin. A lot of things that happened in my life before I was free to be me were great and I wouldn’t trade them for a different path because this is the path I had to walk to be who I am today. All I’m saying is, you don’t have to go as far down that road as I did to be free.”

One wishes her well on the journey ahead.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – Broken Dreams: Another Year Inside Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, he was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 days ago

Book Review2 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds