Featured Articles

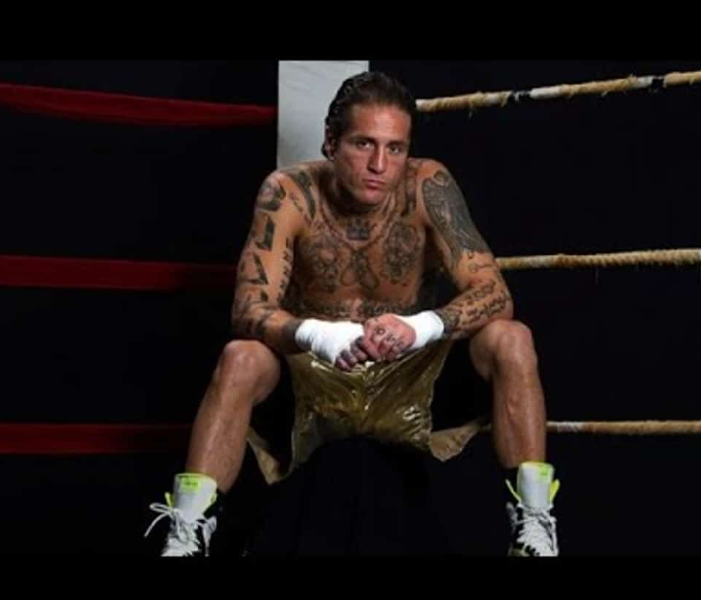

Catching up with Paul Spadafora: A New Beginning for the ‘Pittsburgh Kid’?

Paul Spadafora finished his career with a record of 49-1-1 that included an 8-0-1 mark in world lightweight title fights. It’s a record that smacks of Marciano and Mayweather and yet when someone mentions his name to someone that follows boxing, the first thing that comes to mind is his extensive rap sheet. Many boxers had their demons. Paul Spadafora had them in spades.

Nowadays, Spadafora, the erstwhile Pittsburgh Kid, can be found in Las Vegas where he spends a portion of most afternoons at the DLX Boxing Club tutoring his 17-year-old son Geno in the finer points of the sweet science. “Paul’s doing great,” says Spadafora’s former trainer Jesse Reid who also oversees the training of Geno who has four amateur fights under his belt.

“If it wasn’t for boxing, I would be dead by now or spending my life in prison,” says Spadafora who turned 47 earlier this month. And, we might add, if he were dead, the circumstances of his demise would have undoubtedly been very messy. But let’s start at the beginning.

Spadafora, one might say, had boxing in his blood. His father Silvio was a regional amateur champion as was Paul’s older brother Harry who took it a step further. As an amateur, competing as a light middleweight, Harry achieved a #3 national ranking. He was 3-0 with 3 kayos as a pro before quitting the sport to concentrate on raising his family.

Paul Spadafora’s maternal grandfather Eugene Pelecritti also boxed and get this: the late Joey Maxim, the former light heavyweight champion who is in the Boxing Hall of Fame, is an uncle.

Scientists will tell you that a thirst for boxing cannot be passed on genetically, but some people are apparently genetically predisposed toward addiction. Paul’s father Silvio, a crane operator by trade, was only 33 when he passed away. The papers said he died of a heart attack, but Paul, who was nine years old at the time, is certain it was an overdose.

A younger brother, Charlie, passed away at age 40. Charlie, says Paul, was smoking crack when he died. And Paul says his mother Annie, now 72 years old, has been a drug user most of her adult life.

Paul Spadafora dabbled in cocaine, but his preferred drug was alcohol which his lips first touched at age 6 when he shared some Italian wine with his father. Alcohol was involved in his first serious brush with the law. He and some friends went out drinking. Paul, then 19 years old, was riding in a car that ran a stop sign, begetting a high-speed police chase that ended when the car crashed into a telephone pole, whereupon one of the pursuing officers took out his handgun and fired one shot point-blank into the front passenger side of the car. The bullet lodged in Paul’s left calf.

In his fighting days, Spadafora was a binge drinker. When preparing for a fight, he was as abstemious as a monk, but each victory was cause for celebration and when he celebrated the booze flowed freely.

Some drunks are happy drunks and stay happy until they fall down; others go from happy to surly where they are prone to lash out at someone at the slightest provocation, including the gendarmes if someone happens to call the cops. Spadafora once skirmished with a bevy of cops and, needless, to say, he took the worst of it. “I got Rodney Kinged,” he told the noted British boxing writer and podcaster Tris Dixon, employing a very clever euphemism.

The year after he took a bullet in his calf, Spadafora was arrested for underage drinking. Other alcohol-infused arrests would follow, including arrests for disorderly conduct and public intoxication. But these were small potatoes compared with an incident in the fall of 2003 that would shadow him for the rest of his life.

Shortly before dawn on the morning of Oct. 26, 2003, at a gas station in the gritty Rust Belt western Pennsylvania town of McKees Rocks, Spadafora shot his girlfriend Nadine Russo in the chest with a handgun that he snatched from Nadine’s purse. The incident, of which Spadafora has no memory, was ignited when Nadine drove over a median and flattened two of the tires on his Hummer.

Russo wasn’t mortally wounded – the bullet lodged an inch below her right breast – and when she refused to testify against him, the charge against him was reduced from attempted murder to aggravated assault.

Earlier that year, Spadafora had fought a spirited fight with Romanian/Canadian tough guy Leonard Dorin on HBO. The bout was ruled a draw which enabled Paul to keep his IBF belt and his undefeated record. That would prove to be his final title fight. He had two bouts as a junior welterweight while awaiting his sentencing. The last leg of a 16-month period of confinement was spent in a military-style boot camp where Paul and his fellow inmates were required to work toward their high school equivalency diploma and undergo counseling for drug and/or alcohol abuse. While he was away, Nadine gave birth to Geno.

—

Spadafora’s reckless behavior outside the ring was incongruent with the dedication he showed to his craft. “You have to throw him out of the gym to get him to leave,” said his amateur coach P.K. Pecora. A natural right hander who fought as a southpaw, Spadafora was so obsessed with boxing that he once shadow-boxed for 24 straight hours. “It was just me and the mirror,” he told this reporter.

Spadafora believes that the policeman who shot him robbed him of much of his power, but that it was a double-edged sword as it forced him to become more of a pure boxer. His strong suit was defense. Indeed, few were as slippery. “Boxing enthusiasts in the Pittsburgh area began comparing Spadafora’s defensive skills to those of the great Willie Pep,” said a story in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Spadafora’s lightweight title reign began in August of 1999 with a 12-round decision over Israel Cardona. The title was vacant, having been abandoned by Shane Mosely who left the weight class to chase a fight at 140 with Oscar De La Hoya. In winning, Paul became Pittsburgh’s first world boxing champion in more than 50 years, achieving parity, as it were, with the original Pittsburgh Kid, Billy Conn.

The underdog in the betting, Spadafora out-classed Cardona, winning all 12 rounds on one of the cards and 11 rounds on the others. His first title defense against Australia’s Renato Cornett was even more one-sided. The Pittsburgh Kid won every round before the fight was stopped in the 11th with the Australian a bloody mess.

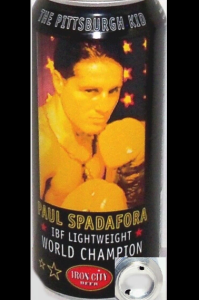

Spadafora’s bout with Cornett was sponsored by the Pittsburgh Brewing Company which commemorated his achievements by putting the boxer’s face on cans of Iron City Beer. Only a handful of local sports celebrities were accorded this honor before him, notably Pittsburgh Steelers legend Jack Lambert, coach Chuck Noll, and the club’s iconic owner Art Rooney. (This is a cool collectable. When asked if he had saved any, Spadafora sheepishly said, “nope, I drank ‘em all.”)

Iron City beer can

Jesse Reid, who came on board before the Cardona fight, would be the longest-tenured of Spadafora’s pro coaches. At various times, other notables – e.g., Emanuel Steward, Buddy McGirt, Pernell Whitaker – assumed the role of head trainer. None, however, left a more indelible impression than P.K. Pecora. The glue of Pittsburgh’s amateur boxing scene, Pecora, a World War II veteran, was more than a boxing teacher; he was a surrogate father to Paul and other kids from the school of hard knocks. Sometimes when Spadafora talks about his relationship with Pecora he is reduced to tears.

Pecora passed away in 1997 at age 68 from a stroke. In tribute to him, Paul had the initials P.K. stitched on his boxing trunks. He would later have the initials inscribed on his body. (Paul Spadafora has this thing for tattoos. Journalist Sean Hamill conducted a census for a 2009 story and counted 24. Each tattoo has a story behind it.)

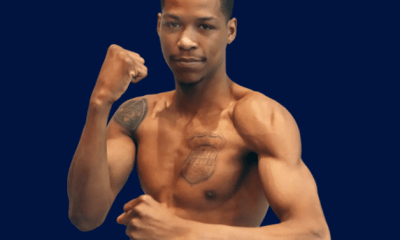

Paul in his younger days

After his release from prison, Spadafora added 10 more “W’s” to his ledger before suffering his first and only defeat, a 12-round setback to Venezuela’s Johan Perez in a bout framed as a WBA 140-pound eliminator with the winner ostensibly owed a crack at Danny Garcia. One of the judges, Glenn Feldman, had it a draw, but the decision was deemed fair. Paul would have one more fight, leaving the sport on a winning note after winning an 8-rounder on a low-budget show at Pittsburgh’s Rivers Casino.

Boxers are by nature notorious alibi-makers. Every defeat has its roots in an extenuating circumstance. When we asked Spadafora what went wrong in the Johan Perez fight – a pre-existing injury, perhaps, or maybe dissension in his camp — we were surprised by his response. “Nothing went wrong,” he said. “Everybody did their job right, except me. I just lost, that’s all.”

Paul Spadafora had one ring engagement that has achieved cult status. In December of 1999, shortly before his match with Renato Cornett, he sparred six rounds in headgear with Floyd Mayweather Jr at a gym in North Las Vegas. The session was recorded and although we have never seen the tape, we will accept as gospel the oft-repeated story that the Pittsburgh Kid was clearly superior.

“I believe that cost me a fight with Floyd,” says Paul. “He learned that there were easier options out there.” Other potential mega-fights never materialized because, in his words, “I kept self-sabotaging myself.”

Is it too late to reprise another Spadafora-Mayweather match-up? How about an exhibition with oversized gloves? If Floyd is going to continue his charade of fighting obscure Japanese MMA fighters and intrepid you-tubers, perhaps he owes it to the fans to man-up once in a while and have a go with someone who just may prove to be in his league. Granted, nobody with any sense wants to see boxers in their mid-40s taking more blows to the head, but Paul and Floyd, steadfast gym rats, are in remarkable shape for their age and there is a precedent for it. When future Hall of Famers Jeff Fenech and Azumah Nelson concluded their trilogy in a legitimate 10-round prizefight, Fenech was 44 and Azumah almost 50.

Our interview with Spadafora accorded him an opportunity to call out Mayweather and potentially get the ball rolling, but he wouldn’t take the bait. “It would be a privilege to get back in the ring with one of the best boxers, if not the best, in the history of the sport,” he says matter-of-factly, “but I’m not a ‘call-out’ kind of guy.”

—-

Paul Spadafora’s travails continued in retirement. In December of 2016, he stabbed his half-brother Charlie in the leg during a fracas at the home of his mother. No one came forward to post his $100,000 bail and he spent Christmas in the Allegheny County Jail. More recently he was arrested following an altercation at a tavern in the blue-collar Pittsburgh suburb of Crafton.

His relationship with Nadine seems to have mellowed after years of tumult. She was in Las Vegas for seven years working in a wellness clinic before Paul quit his job as a tree surgeon and came west to join her. The four of them — Paul and Nadine and Geno and the family dog, a very large pit bull that Paul named Tiny – are living under the same roof once again.

Who knows what the future holds for Paul Spadafora, but at the moment he seems to be in a good place. This story may yet have a happy ending.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Arne K. Lang’s latest book, titled “George Dixon, Terry McGovern and the Culture of Boxing in America, 1890-1910,” has rolled off the press. Published by McFarland, the book can be ordered directly from the publisher (https://mcfarlandbooks.com/product/clash-of-the-little-giants) or via Amazon.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates