Featured Articles

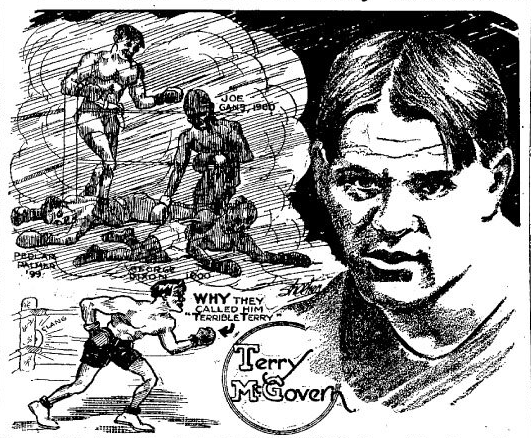

Terry McGovern: The Year of the Butcher, Part One – A Man Invincible

It is the night of September ninth 1899 and Pedlar Palmer is dreaming of home, the pattering of rain against New York glass carrying him back, perhaps, to his native England. Palmer had won the world’s bantamweight title in London and had defended it in London turning away both the best of British and the Americans that dared to sail. Now, he had sailed, to defend his status as the very best in the world. The blood that whispered in his veins was fighting blood; his grandfather boxed Abe Belasco, a technician of the bare-knuckle era, and ran with Daniel Mendoza, the godfather of scientific pugilism; his great grandfather boxed the legendary Tom Belcher.

For him, it was always to be the cobbles and history records only a sliver of his combat. It records not a single loss. Palmer slept well the night of September ninth 1899, the sleep of a man invincible.

In the city, Terry McGovern dreamed too. Blood-sodden punches tearing the life from helpless giants. Within the next twelve months he will defeat, by destructive knockout, the reigning bantamweight, featherweight and lightweight champions of the world. It will be easy.

It is the Year of the Butcher.

Just as the wolf does not train to be the wolf, Palmer did not spar in preparation for the looming confrontation but rather honed himself to a vibrating peak under the tutelage of a man from the same pack, former lightweight contender Sam Blakelock. Blakelock spoke little and laughed less, but walked with Palmer before breakfast, ran with him after, read the newspapers with him before lunch, worked with him after, steam billowing from his body just as it steamed from Palmer’s when the heat left the day. They were a team, one of the most formidable in the world.

For all that, they were different, both as men and as fighters. Palmer spoke lightly and made friends wherever he went, though he disliked crowds and attention. Where Blakelock had embraced a more direct style in his doomed pursuit of the great Jack McAuliffe, Palmer wore his alias “Box O’ Tricks” proudly and was often described as the cleverest man in his division. A deluxe spoiler and multi-range stylist he was adept at solving his opponent over the canvas, and the fact that he had never seen McGovern lift his hands in the ring did not concern him.

“I never fight two men the same way,” he explained when pressed by American journalists for strategy. “A man can never tell how he is going to fight until he feels his opponent out.”

The press felt sure though that it would be Palmer victory on points or a Palmer loss by knockout. McGovern was not yet known to be the forefather of every destroyer who would ever box under the Marquis of Queensberry Rules, but he was already regarded by boxing scribe Willie Green as “a miniature John Sullivan” and “the hardest hitting little man in the ring.”

He stayed in Brooklyn, close to home, unperturbed by the stream of company that caused Palmer to shift camps although he did insist, unusually, upon a degree of privacy for his training. He did spar, savagely and relentlessly, in the main with the lightweight contender Tim Kearns, and from bright eyes and giddy face he did claim to love to fight, whoever, wherever.

He “took enough wallops to unnerve an ordinary scrapper,” reported The New York Sun. “He got it hard on the jaw often, but all the blows did was shake him a trifle.”

To take it. The definitive mission for the true ring savage who would be great, to take it and to prove you could take it, to oneself first and foremost, to the world and everything in it besides.

“Well, you see, I take a punch to give two,” McGovern offered. “I feel out my man to see if he’s a hard hitter…the only way to ascertain this is to take one or two you know.”

They ran him like a dog and then rubbed him down with witch-hazel. They fed him meat, which he loved and was “given to as much as possible.” Then they took turns fighting him and by nine he was in bed and asleep. When he reached the required poundage, everything stopped, he rested, suddenly and preternaturally still, patiently awaiting the removal of the invisible chain.

McGovern opened a narrow betting favourite and the odds widened the nearer came the fight, to the great consternation of newspapermen. “There should be no odds,” argued The St. Paul Globe. “The men are so evenly matched that the betting should be the same…Palmer is far and away the better boxer as far as skill is concerned [and] the Britisher’s record is superior.”

The great heavyweights agreed to a man, Bob Fitzsimmons picking Palmer to win by experience, John L. Sullivan, James J Corbett and Jim Jeffries all declining to make a pick, calling an even fight. Tom Sharkey stuck out his neck in predicting a late knockout for McGovern.

The day before the combat, Palmer visited with the Westchester Athletic Club in Tuckahoe, New York, and examined the canvas, tightened the ropes. McGovern reclined among newspapers, his eyeballs drying in the stillness of his head, his captivity lengthened by a twenty-four-hour delay enforced by weather. Having risen that morning before the truth of dawn to weigh in comfortably under the 116lb limit, each man bathed in the luxury of a rehydration period close to thirty-six hours after the champion refused to be re-weighed on the fight’s new date; they would bring the best of themselves to the ring the next day.

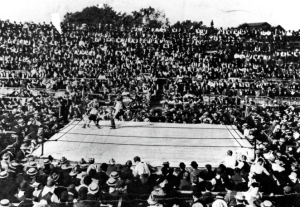

Thirty-six hours trickled by. At the site of the fight, pandemonium. An unexpectedly huge and enthusiastic turnout saw a scrum in the cheap seats that took the best part of an hour to settle and did irretrievable damage to the wardrobe of numerous spectators. Both fighters eschewed the crowd’s intensity, McGovern smiling his way to the ring behind his younger brother, who brandished both the American and the Irish flag. Palmer seemed even more relaxed, “all agility” according to one ringsider, moving lightly from one rope to the other, smiling, almost sanguine, once more a man invincible.

The-Scene-at-Tuckahoe

He was “the cleverest fighter in the world in the opinion of many” according to one preview and was expected to control McGovern in the early stages even by those that predicted a win for the challenger. He had controlled, after all, the immortal George Dixon some three years earlier in a six round draw at Madison Square Garden. The final round had been tough for the Englishman, but early he easily nullified Dixon’s aggression with his dazzling speed, stiff left hand and tactical brilliance. Notably the smaller man in that contest, it was considered unlikely that if Dixon, in his genius, could not place Palmer under control early, McGovern, who was no bigger than Palmer and had but a sliver of Dixon’s art, would struggle.

A little over two minutes after the opening bell Palmer was roiling on the canvas in a semi-conscious stupor, lunging for and missing the bottom rope in a heartfelt but futile attempt to rise. McGovern had turned his brain in his head with a devastating combination landed behind punishment that the wire-report called “swift and terrible, his hands working like piston-rods.” Palmer was not just beaten but outclassed by an opponent who kept his promise to “take one or two” to measure the champion’s artillery, and found it wanting. Palmer, for all his cleverness and experience, was doomed from that moment as McGovern elected merely to walk through him and “batted him to semi-insensibility.”

McGovern bared his teeth when Palmer landed those two blows and the whirlwind attack that followed “carried his opponent’s cleverness before him like chaff” according to The Brooklyn Eagle. A right hand to the heart seemed momentarily to stiffen the champion and perhaps even force him to take a belated knee, though he received no count.

“McGovern’s body work was simply awful,” The Eagle continued, “and the beating on the diaphragm…left Palmer in much the same condition as Corbett [in his fight with Bob Fitzsimmons]. His body was temporarily paralyzed from the blows.”

At the crucial moment the surrealism which infused the venue in the presence of the enormous black Kinetoscope and the trampling of the brisling crowd deepened when the timekeeper’s hand slipped and the round came to a sudden and premature end after just a minute of action. Referee George Siler waved them back in and a stunned Palmer, clearly shocked by the brutality of the assault surrounding him, attempted to clinch; McGovern fought and writhed his way free and Palmer clinched again – and again. Finally, McGovern ripped free and landed a whistling hook on or just above the jaw and Palmer was over.

Up at five he tried to stall but finally was cornered by a fighter so bent upon his destruction that he had begun to miss, until at last McGovern found him flush with an uppercut that drove his head up and away. As he reeled the new champion landed the left-hook that was likely the punch most responsible for his victory and as he tried to fall McGovern found him again with a right hand to the temple, turning his brain in a third new direction in just a single second. Not all accounts of the fight have the referee bothering to finish the count before he raised McGovern’s hand in triumph.

“What was it hit me?” the deposed champion asked when at last he could speak.

“Palmer kept falling over,” complained Mrs. McGovern as her husband cooed their newborn baby on his knee, his face unmarked. “It wasn’t very exciting?”

“It came off much quicker than I expected,” McGovern agreed, directing his remarks towards the pressmen that surrounded him. “I thought it would go at least ten rounds and maybe seventeen,” he added with disturbing specificity. “But I had no doubt as to the result. I am now ready to meet them as they come. Starting with George Dixon.

“Isn’t he big for his age?” he asked, offering the child.

Dixon had instructed his manager to challenge the winner, though he did not attend himself. The two men split around $26,000 in cash and assets, an enormous purse for bantamweights and not something Dixon could ignore any more than he could have ignored the sense that he was about to become a part of another man’s destiny. But George Dixon was not so assailed. He had defended his featherweight title eight times in 1899 and was relaxed about making the latest in a long line of new sensations his first defence of the new century.

“I’ll finish him before the tenth,” McGovern insisted, still smiling.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review5 days ago

Book Review5 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds