Featured Articles

Rest In Peace Ken Buchanan

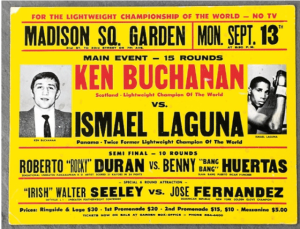

We don’t get many great ones in Scotland. Ken Buchanan, who was confirmed to have died today, was one of them, having held the lightweight championship of the world in the highly competitive era of the 1970s, losing it to perhaps the finest champion of them all in the shape of Roberto Duran – and in questionable circumstances at that.

The temptation is to tell the wonderful story of Ken Buchanan in three fights, and I will succumb to that temptation, saying in addition only that the determination and dignity that Buchanan held in his difficult later years impressed me almost as much as his wonderful fighting career. That he did great things in tartan shorts often despite of and not because of a country that failed to support him as richly as he deserved. That the British Boxing Board of Control’s failure to recognise him as world champion when literally the whole of the rest of the boxing universe did is the most shameful decision in the history of that storied organisation. Ken had nothing like the financial, administrative, promotional, and sometimes fistic help that he should have had. Buchanan, perhaps more than any of the great British fighters, achieved what he achieved alone.

That is why we find Buchanan at his mother’s funeral in the late 1960s essentially retired from the sport before he has even been tested. Buchanan was not a very Scottish fighter. He didn’t wade in, workmanlike, “honest”, aggressive; that was his lightweight rival, another fine Scottish fighter named Jim Watt, but it was not Ken. Ken boxed with grace and flamboyance, chose distance, and controlled it, he made superfluous moves and eschewed economy. The style hid iron. Buchanan was stopped just once and that loss had absolutely nothing to do with his chin, as we shall see. Motivated by his remembrance of his mother’s belief that he was made to do something in the sport of boxing, he set out once again in search of greatness. Almost immediately he was robbed in his attempt to win the European lightweight championship from Miguel Velazquez, out in Spain. The great Scottish sportswriter Hugh McIlvanney wryly noted that Buchanan would have had to have produced a death certificate for the Scotsman to get something out of a fight he clearly deserved to win.

Throughout Ken’s career, money men, among them the top British promoter Bobby Neil, tried to change his style, turn him into a workman’s puncher, but Ken just calmly turned them away, choosing his moves based upon freedom rather than cash. This is what made the fast turnaround after the Velazquez debacle so fascinating to me. Buchanan was essentially waiting for a stay-busy fight after winning the British title when he was called directly by Jack Solomons, probably the best-connected promoter and fixer in the country at that time.

“How would you like to fight for the world title you Scots git?” was Jack’s opening gambit; Ken thought that Jack had called him up as a joke, promoted by his father, Ken’s constant companion but a man fond of a joke. Jack explained clearly – the people who handled world champion Ismael Laguna were after a soft touch; a stand-up boxer who wouldn’t give Laguna any trouble, a “patsy” in the parlance of the time. Buchanan was furious.

“A patsy? Is that what they think of me in America? Get me the fight Jack and I’ll show these people what us Scottish patsies are like.”

Buchanan’s date with destiny was set for September 26, 1970 in San Juan, Puerto Rico. To further discomfort the Scotsman the fight would be fought at 2pm with temperatures soaring to 100 degrees Fahrenheit. “I knew there was no promoter in Britain ready to put up money for me to have a shot at the title,” he remembered in his 2000 biography The Tartan Legend, “so I’d have to go for this in a big way.”

The champion, Ismael Laguna, was a wonderful fighter. In 1965 he had defeated the mighty Carlos Ortiz in a narrow decision that must be seen to be believed. Laguna inverted his combinations, turned square against the lethal Ortiz to lead with his right, a baffling, extraordinary execution. It remains one of the finest maverick performances I’ve ever seen against a genuine all-time great and although Ortiz avenged himself and reclaimed his title, when Ortiz was out of the picture Laguna once again rose to the top. Buchanan and his father developed an audacious plan that only another maverick could conceive of: they would travel 4,000 miles from home and outbox this man to a 15-round decision.

Buchanan, in many ways, was ahead of his time and that he was undertaking sprints as interval training in the build-up to the San Juan contest may have been the single most important factor (outside of his brilliance) in winning that fight. Bathed in sweat and “unable to fill my lungs with air” Ken battled the oppressive heat as keenly as he did his opposition in the ring. This training mirrored Ken’s style in the ring – movement, control of the distance, then lengthy combination punching or a period of infighting under maximum commitment, then back on his toes. Almost as important was may have been the shuffling of the officials prompted by Ken’s manager, Eddie Thomas, who had heard that a judge and referee had been imported by Laguna’s team for the occasion.

Ken boxed early and was perhaps out-pecked – he stepped in to provide pressure through eight and the fight was balanced on a knife-edge and remained there through twelve. What really made the difference in this fight was not Ken’s skills and quickness and what is perhaps the most cultured left hand in the history of British boxing, but his decision in the championship rounds to attack. “By the twelfth round we are both tired. Really lead-weight tired. But Laguna won’t give in…I decide to change my tactics. I decide to go for him.”

It was just enough. Ken Buchanan became the new lightweight champion of the world by split decision, both his eyes closed and “at the limit of [his] endurance.”

Buchanan fought his first defence in February of 1971, outpointing Ruben Navarro in LA and fought his second and last defence in a rematch against Laguna. Made in New York, this battle was every bit as torrid as the first, a savage cut to his left eye hampering him throughout and forcing an adjustment that is every bit as much a part of Buchanan’s legend for me as his forthcoming meeting with Roberto Duran. His legendary jab hampered by that damage to the left eye, Buchanan fought squarer, just as Laguna had against Ortiz all those years ago, the injury forcing him in to what McIlvanney called the “slugger’s stance.” I’ll bow to his summary of this fight:

“Most boxers, faced with the demand for such an adjustment, would make a respectable lunge at it for a few minutes, then sag into resignation. The Scottish world champion, whose blindingly sudden and confusingly flexible left jab is not only his most telling weapon but the triggering mechanism for all his best combinations, might have been forgiven if he had gone that way…far from wilting he gained in assurance and authority as the fight moved into the final third of the contest. Time and again he turned back the spidery aggression of Laguna.”

For Buchanan, I’m sure it was nice just to have McIlvanney in attendance. Almost no British press had followed him east for his shot at the title and the reception at home was underwhelming, not least by the BBBC’s preposterous stand over Buchanan’s championship honours. Now, he had earned his status as one of Britain’s great champions.

It is a status he enjoyed at the time of his death today at age 77, a year after his diagnoses with dementia, a status he will always enjoy despite his loss of his lightweight title in his next defence against his nemesis, Roberto Duran.

Duran stopped Ken Buchanan in the thirteenth round of their 1972 Madison Square Garden match, but it is time now to be explicit: the refereeing in this fight was questionable. Johnny LoBianco allowed Duran to foul Buchanan throughout. Sports Illustrated adjudged from ringside that Duran “used every part of his anatomy, everything but his knee” in his pursuit of the title.

Buchanan was even more direct: “I thought I signed up for a wrestling match, not a boxing contest. He hit me in the balls a couple of times without so much as a nod from the referee.” In the thirteenth, Buchanan, trailing on the cards, felt he had one of his better rounds but at the bell, “I turn towards my corner and in the same moment Duran lunges…with a punch that went right into my balls.” The punch was so hard that it split Buchanan’s protector. Examined by a doctor after the fight he was found to have significant swelling of the testicles. The referee, incredibly, didn’t even admonish Duran for throwing a fight-finishing punch after the bell while simultaneously claiming that the punch had been “to the solar plexus.”

To be clear, Duran was better than Buchanan. It’s almost impossible to envisage Buchanan turning the fight around and however he personally felt about the thirteenth, if he received four rounds on a scorecard, that scorecard would be generous. But it is also wrong to see anyone drop his title in such circumstances and the unfortunate event saw the beginning of Buchanan’s slide from relevancy and then, later, mental health. He waited by the phone for far too long for Duran to call him up and offer a rematch. Whatever is to be made of it, Duran had no interest in providing one, and in Buchanan’s defence, it’s probable that he never fought a fighter as good as Ken during the whole of the rest of his lightweight reign. Buchanan took it badly, so badly he even flew to North America in the 1990s to see if he could track Duran down and have it out with him. Fortunately, Buchanan didn’t get much further than some downtown bars where he was still fondly remembered by some of the patrons.

Buchanan’s life post-boxing was difficult, but never pitiful. He was proud and however difficult things got, he remained proud. Last year, and just in time, he was in attendance as a statue of him was unveiled on Leith Walk in Edinburgh where he ran as a boy.

Gone now, he will never be forgotten in Scotland. Blessed with speed and great heart he made of himself what he could and it turned out to be just about as much as a Scottish fighter has ever made of himself. To end I offer a quote from The Fight Game In Scotland, a book written by Brian Donald who himself boxed Buchanan when both were Edinburgh teenagers. Brian ran 0-3 but began a lifelong friendship with Buchanan who was always ready to offer the hand of friendship to his defeated opponents.

“Buchanan, like a top-grade malt whisky, held his own in any foreign environment no matter how distant he was from his native shores…he was and remains one of the most accomplished British fighters to fight in foreign rings. His ring style was in some respects a metaphor for his own personality, elusive and tough, and the soaring singularity of his talent was matched by an equally single-minded determination that nobody, but nobody, knew better than Kenny Buchanan what was good for him.”

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers