Featured Articles

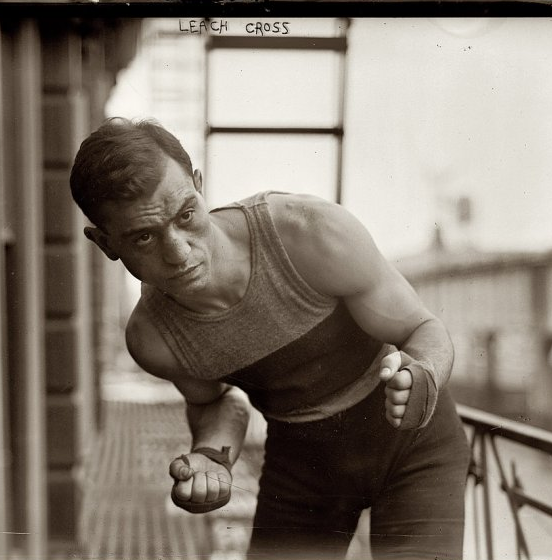

Leach Cross vs. Mexican Joe: A Great Boxing Rivalry Buried in the Sands of Time

The Jan. 14, 1913 fight between Leach Cross and Mexican Joe Rivers was a humdinger, but for some fight-goers it was a night to forget. The event was oversold. The aisles were jammed with standees and ticket-holders arriving late were left out in the cold when the fire marshal ordered the doors to be shut. Some of those that made it inside discovered that their wallet was missing. In the lobby of the arena and outside on the street, pickpockets worked the crowd to great effect. Such were the hazards of attending a major boxing show in New York during the early years of the twentieth century.

Cross vs. Rivers – the first salvo of a great rivalry – was staged at the Manhattan Casino which was situated on the corner of 155th Street and Eighth Avenue in the upper reach of Harlem. This warrants a clarification.

The word “casino” has come to be associated with gambling. Back in those days, it carried no such inference. The most salient image was that of a place where couples came to dance to a live orchestra. Harlem hadn’t yet become a signpost of Black America. In 1913, it had a burgeoning population of upwardly mobile Jews who had escaped the tenements of the Lower East Side. And Leach Cross, born Louis Wallach to immigrants from Austria, was one of them, a landsmen.

Cross (pictured) and Mexican Joe were lightweights. No title was at stake when they locked horns that night in Harlem or in any of their subsequent meetings. Indeed, both were considered a notch below the topmost fighters in their weight class. However, it was a very sexy division which owed to two factors. The heavyweight class was bereft of charismatic fighters other than Jack Johnson whose career was in limbo because of legal problems. And in no other division was the talent pool as deep. “In those days,” reminisced the colorful fight manager Dumb Dan Morgan, “there was a good lightweight on every streetcorner.”

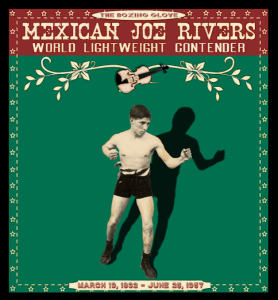

The principals: Leach Cross and Mexican Joe Rivers

Leach Cross didn’t look like a fighter. “He had the lean, cadaverous appearance of the professional distance runner who has overtrained,” wrote one reporter. But his appearance was deceiving. Prior to meeting Rivers, he had knocked out Young Otto and One Round Hogan, reputable opponents, and had feathered his cap with a clear 10-round decision over Battling Nelson. True, the Durable Dane was then past his prime, but in his heyday the former two-time lightweight champion was the most talked-about non-heavyweight on the planet.

By and large, young Jewish men were avid fight fans and from a ticket-selling standpoint it mattered greatly that “Leachie” was a member of the tribe. He had another distinction that made him stand out. He was a dentist with a flourishing practice in the Bowery.

Unlike Leach Cross, Mexican Joe Rivers, who turned pro in 1908 at age 16, looked very much like a boxer. Three inches shorter than Cross at five-foot-four, he had a well-defined physique. “Physically,” said a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, “Joe is one of the grandest pieces of furniture ever seen in a ring. His body is the body of a sculptor’s dream.”

Mexican Joe had far less experience than Leach Cross but had fought stiffer competition. He had split two fights with future Hall of Famer Johnny Kilbane and with Joe Mandot, the Pride of New Orleans, and had TKOed Frankie Conley, an outstanding fighter from Wisconsin, after their first encounter ended in a draw. His most famous fight had come the previous year against world lightweight champion Ad Wolgast. In the thirteenth round of a 20-round fight, Rivers and Wolgast landed simultaneous knockout punches. Rivers hit the canvas first, Wolgast landing on top of him, whereupon referee Jack Welsh helped the semi-conscious Wolgast to his feet and named him the winner. The queer ending provoked a long-running debate.

Prior to meeting up with Leach Cross, Mexican Joe had fought exclusively in California. The West Coast vs. East Coast angle imbued their fights with a bit more cachet in a day when the country wasn’t as homogenized.

Cross-Rivers I (Jan. 14, 1913)

Those that navigated their way to their assigned seat without incident were treated to a riveting fight. “The bout never lagged,” said a reporter. “Action was rife from start to finish.”

Cross put Rivers on the canvas in the second round, but Rivers — “the hot tamale from out West” in the words of a Connecticut scribe — was never deterred from pressing the action and at the final bell of the 10-rounder, Cross returned to his stool “very distressed.”

This was the no-decision era of boxing in New York. Prizefights were ostensibly sparring exhibitions (wink, wink) and referees were prohibited from naming a winner. Bets were decided based on the verdict of a designated ringside reporter or by the consensus of a panel of reporters whose judgments were culled from the next day’s newspapers. Chalk this one up to Joe Rivers, but softly, as few would have complained if the verdict was returned as a draw.

Cross-Rivers II (April 8, 1913)

Not quite 11 weeks later, Leach Cross and Mexican Joe Rivers had a do-over. The venue was St. Nicholas Arena on 66th Street, a former indoor ice skating rink. There was no repetition of the hooliganism that had scarred the first meeting. The promoters, the McMahon brothers, Eddie and Jess (the latter was the grandfather of WWE impresario Vince McMahon) were on a short leash and extra security was hired to keep order outside the arena and turn away would-be gate crashers.

Cross and Rivers delivered another crowd-pleaser. The 10-rounder was a “whirlwind battle” wrote the stringer for the Chicago Inter-Ocean.

Many of the rounds were undoubtedly tough to score as one finds a great deal of variation in round-by-round reports. What everyone seemed to agree on, however, is that Cross showed more stamina than in the first meeting, dominating the ninth round and having a shade the best of it in the final stanza. But, in the eyes of New York’s foremost boxing writer Robert Edgren, his rally came too late.

“Rivers won easily” wrote Edgren, the sports editor of the New York Evening World. Rube Goldberg, who would achieve fame as a cartoonist but was then covering fights for the New York Evening Mail, thought otherwise: “It would be unjust to either man to call the fight anything but a draw,” he wrote.

A survey of 11 ringside reporters by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle found that six favored the Mexican, two gave it to Cross and the others had it a draw.

“It seems that only a longer battle will satisfy to determine which is the better man,” said a correspondent for a Buffalo paper. And before the year was out, he got his wish. The Cross-Rivers rivalry went west to Vernon, California, an industrial suburb of Los Angeles, where fights were allowed up to 20 rounds.

Cross-Rivers III (Nov. 27, 1913)

The third meeting between Rivers and Cross created a lot of buzz in the City of Angels. Three days before the Thanksgiving Day battle, on Nov. 24, a joint workout in Vernon attracted a reported crowd of 4,000.

Vernon was Mexico Joe’s turf. He was the “house fighter” at promoter Tom McCarey’s wooden pavilion. Ten of his previous 13 fights took place in this very ring.

Cross-Rivers III started at 3:30 in the afternoon and concluded after sundown with the ring illuminated by lights that were turned on as the fight was in progress.

Rivers knocked Cross to the canvas with a right-left combination in round four and again in round 12, but on each occasion Cross fought back feverishly. In round 19, with Rivers plainly ahead, there was high drama as the match turned sharply in favor of the New Yorker; Cross battered Rivers from pillar to post. But Rivers weathered the storm and, as it turned out, Cross had exhausted all of his bullets. He had no argument when the referee awarded the fight to Mexican Joe.

“It was the greatest battle ever fought in a southern [California] ring,” gushed Harry A. Williams of the LA Times.

Rivers-Wolgast IV (Aug. 11, 1914)

Prizefighters invariably have an alibi to explain why they lost, and Leach Cross had a good one. Seventeen days before the bout, he had fought lightweight champion Willie Ritchie in a non-title 10-rounder at Madison Square Garden and he was still feeling the effects of that hard tussle. “With proper rest,” said Cross, “I would have beaten this guy.”

That was sufficient inducement for promoter McCarey to summon up yet another sequel.

The fourth and final installment of the rivalry was redemption for Leach Cross who was deemed the winner in a bout so absorbing that one of the spectators passed out from all the excitement.

Mexican Joe piled up points in the early rounds, but he lost some of the steam on his punches after suffering a bad cut on his lower lip in round five. Rivers landed the best punch of the fight in round 18, a left hook to the jaw, but he got discouraged when Cross stayed upright and failed to press his advantage. Had he done so, he would have likely pulled the fight out of the fire as the match very close.

How close was it? “Cross won by a shade as fine as that cast by a single strand of a spider’s web on a foggish day,” said the ringside reporter for the Los Angeles Evening Express.

And that was that; 60 rounds of boxing spread across 20 months with interruptions for a slew of intervening fights and when it was all over, one couldn’t say that one man was plainly superior. As rivalries go, Cross vs. Rivers will never rank with boxing’s most storied multi-fight rivalries, but it was chock full of pregnant moments.

Postscripts

Leach Cross was a wealthy man when he retired from boxing in 1916. With his ring earnings he purchased an 80-unit apartment building in Hollywood. He disposed of his California real estate holdings following the stock market crash of 1929, resumed his dental practice in New York, and kept his hand in the fight game as a referee and a judge. He was well-off financially when he passed away in 1957.

Mexican Joe Rivers had his last fight in 1924 in the Los Angeles County community of San Fernando. It was a 4-rounder which was all that the law allowed after voters in the Golden State had approved a constitutional amendment to abolish prizefighting in the November elections of 1914. When things were going good, Joe lived high. He owned a big touring car, expensive jewelry, and dozens of custom-made suits. In 1955, when he was 63 years old, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times found him living alone in a windowless room in a flophouse hotel, his only possession a 200-year-old violin passed down from his father. The reporter discovered that Mexican Joe wasn’t actually a Mexican. A fourth-generation Californian, born Jose Ybarra, Joe was of Spanish and Mission Indian stock.

Arne K. Lang’s third boxing book, titled “George Dixon, Terry McGovern and the Culture of Boxing in America, 1890-1910,” rolled off the press in September of last year. Published by McFarland, the book can be ordered directly from the publisher or via Amazon.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates