Featured Articles

Boxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

Boxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

There was a time when Madison Square Garden on the eve of the Puerto Rican Day Parade belonged to Miguel Cotto.

Cotto fought from 2001 through 2017, going in tough more often than most elite fighters of his era en route to compiling a 41-6 (33 KOs) ring record. He was a first-ballot Hall of Fame inductee who personified dignity and grace, both in and out of the ring.

Top Rank did a brilliant job of building Cotto as a fighter and gate attraction. Part of that process was creating the tradition of Miguel fighting in the main arena at Madison Square Garden on the eve of the Puerto Rican Day Parade. He did it four times in five years, beating Muhammadqodir Abdullaev (2005 – KO 9), Paulie Malignaggi (2006 – W 12), Zab Judah (2007 – KO 11), and Joshua Clottey (2009 – W 12). For an encore, he knocked out Sergio Martinez in 2014.

That history was a distant memory when Top Rank hosted a fight card in the Hulu Theater at Madison Square Garden on Saturday night – the eve of this year’s Puerto Rican Day Parade. There were eight fights on the card. Each fight featured a local ticket-seller or a fighter who Top Rank is trying to build in a “learning experience.“ Only one of the fights was competitive. The A-side fighter won all eight bouts.

Some impressions:

Nisa Rodriguez (now 2-0) looked like a professional fighter until the fight started. Her opponent, Jordanne Garcia (4-4-3), didn’t look like a fighter at all. Garcia is winless in five outings dating back to 2019. And the four women she beat before that have a grand total of zero wins among them. Garcia didn’t know how to throw punches, so she didn’t. She simply bulldozed forward, grunting, and held. Rodriguez (a New York City police officer) sold some tickets, won every round, and her fans seemed happy.

Lemir Isom-Riley (now 4-3, 2 KOs, 2 KOs by) fought like the losing combatant in a toughman contest. But this was boxing. Ali Feliz (2-0, 2 KOs) knocked him out in the first round.

Ofacio Falcon (11-0, 6 KOs) won every round in a dreary match-up against Antonio Dunton El Jr (5-3-2, 2 KOs).

Jahi Tucker (11-1-1, 5 KOs) vs. Quincy LaVallais (17-5-1, 12 KOs) was troubling. Tucker had stepped up the level of competition in his last two fights and suffered a loss and a draw. So he went back to fighting softer opposition. Tucker hurt LaVallais (who seemed out on his feet and was saved by the bell) at the end of round one. Quincy never recovered. He took head shot after head shot from round two on. Tucker loaded up again and again but couldn’t put him away. Eric Dali might be the best referee in New York. He should have stopped the bout but didn’t. The fight went the distance with Tucker winning all eight rounds on each judge’s scorecard. What made it particularly ugly was that Jahi showboated in a way that was particularly demeaning to his opponent. At one point, with LaVallais backed into a corner, Jahi put one hand behind his back and pounded away with the other. With ten seconds left at the end of round six, he retreated to his own corner and stood disdainfully with his arms draped on the ring ropes. Let’s see how much showboating Jahi does if and when Top Rank matches him competitively again.

Andy Dominguez (11-1, 6 KOs) vs. Cristopher Rios (10-2, 7 KOs) was a good spirited action fight. Dominguez emerged with a majority decision victory but the scorecards could have gone either way.

Tiger Johnson (13-0, 6 KOs) won a snoozer over Tarik Zaina (13-2-1, 8 KOs).

Bruce “Shu Shu”Carrington (12-0, 8 KOs) looked good in stopping Brayan De Gracia (29-4-1, 25 KOs, 2 KOs by) in eight rounds. With the caveat that De Gracia had been in only one fight since 2022 and lost it. Carrington has the most upside of any fighter who was on the card. He brings a healthy dose of mean into the ring and isn’t content to coast to a decision. He wants to hurt his opponent and knock him out.

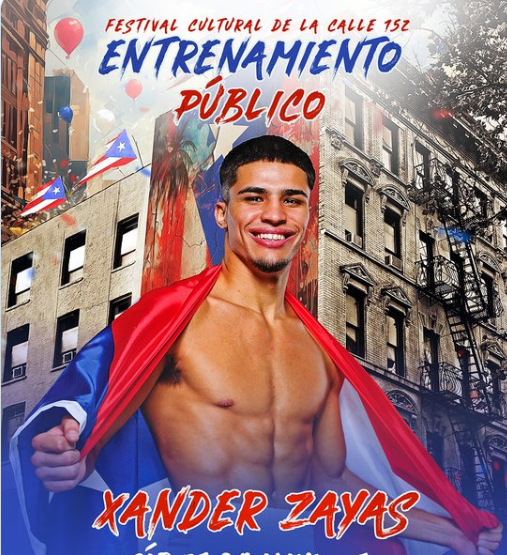

The main event matched Xander Zayas (19-0, 12 KOs) against Patrick Teixeira (34-5, 25 KOs, 1 KO by). Teixeira looked like a shot fighter from the opening bell. His timing and balance were off. His punches were arm punches. And Zayas couldn’t put him away, which suggests a ceiling on Xander’s future.

Miguel Cotto elevated Madison Square Garden. And Madison Square Garden elevated Cotto. Those times are gone.

***

On April 5, 2024, a 27-year-old professional boxer named Ardi Ndembo was knocked unconscious in a Team Combat League fight contested in Coral Gables, Florida, and placed in an induced coma by doctors who were trying to save his life. He died three weeks later.

Ndembo had been knocked unconscious twice in sparring sessions in Las Vegas gyms during the month immediately preceding the fatal fight. He was medically unfit to fight in Florida.

In early-May, the Association of Boxing Commissions issued a statement urging that the Florida State Athletic Commission “conduct a full and transparent regulatory investigation into the circumstances surrounding Ardi Ndembo’s death.”

On May 21, Florida State Athletic Commission executive director Tim Shipman declared, “We’re not investigating the case. And as far as our procedures are concerned, there’s nothing we’re going to change.”

I did investigate the case. My report was published on June 4 in The Guardian and can be read in full here:https://www.theguardian.com/sport/article/2024/jun/05/the-death-of-ardi-ndembo-was-a-fatal-boxing-fight-preventable

Ndembo was killed in a fight conducted under the auspices of an organization called Team Combat League. A video of the fatal fight can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AVxxgSPVV7A

A video of Ndembo being knocked unconscious by Efe Ajagba in the Bones Adams Gym in Las Vegas can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e3l34zH2n50

A video of Nbembo being knocked unconscious by Patrick Mailata at the Split-T Management Gym in Las Vegas can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pRmhMmxPwlM

The video of Ndembo being knocked unconscious by Mailata was posted on RealFightStories.com (a site founded by combat sports journalist Mike Russell). The video has an arrow on the screen pointing to a spectator standing by the ring ropes as Ndembo is knocked out and identifies the spectator as Dewey Cooper.

Dewey Cooper is president of Team Combat League.

Mike Russell is light years ahead of everyone else in investigating Ardi Ndembo’s death. Look for his follow-up work on the issue at RealFightStories.com

ABC president Mike Mazzulli oversees combat sports for Mohegan Sun. The New York franchise of Team Combat League hosts its fights at Mohegan Sun. That gives Mazzulli the authority to investigate what the Florida State Athletic Commission won’t.

Meanwhile, the Florida State Athletic Commission has forfeited the right to tell anyone that the health and safety of fighters is its primary concern. Clearly, it isn’t.

Ardi Ndembo

***

Does anyone remember Marselles Brown?

Brown was a seven-foot club fighter who compiled a 33-18-1 (25 KOs, 13 KOs by) ring record between 1989 and 2016. Along the way, he was knocked out by Trevor Berbick, Lamon Brewster, and Tommy Morrison.

Why am I mentioning this now?

Brown has a son named Jaylen. Yes, that Jaylen Brown. The Jaylen Brown who’s an NBA superstar and is on the verge of leading the Boston Celtics to the NBA Championship.

***

It’s often said that the older we get, the more we think about long-ago times. In Jerry Izenberg’s case, that’s good. Izenberg is 93 years old. And his latest book – Larry Doby in Black and White (Sports Publishing) – is one of his best. So let’s step outside the insular world of boxing and take a look at a man who helped reshape America more than seven decades ago.

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson shattered baseball’s color barrier. Eleven weeks later – on July 5, 1947 – wearing a Cleveland Indians uniform, Larry Doby followed suit

Robinson was on a team that welcomed him with open arms. Doby entered a mostly cold locker room that included teammates who refused to shake his hand. Robinson was in Brooklyn – a borough of New York City that thrived on diversity. Doby was in Cleveland, a city with public schools that were still segregated, restaurants that often refused to serve black patrons, and movie theaters that confined people of color to the balcony.

Except for the World Series, the American and National Leagues were separate institutions with separate administrative structures. There was no interleague play.

When New York Yankees general manager George Weiss was asked after Robinson’s debut whether the Yankees were interested in signing a Negro (the accepted term in those days), he responded, “Our fans are different. Do you think a Wall Street stockbroker would buy season box-seat tickets to see a colored boy play for us?”

Thirteen years later, when Calvin Griffith moved his team from Washington to Minnesota where they became the Minnesota Twins , Griffith declared, “I’ll tell you why we came to Minnesota. It was when we found out you only have fifteen thousand colored people here. We came here because you’ve got good, hardworking white people here.”

“Jackie got all the credit for putting up with the racists’ crap and abuse,” Doby later told Jet magazine. “He was the first. But the crap I took was just as bad. Nobody said, ‘We’re going to be nice to the second Negro.'”

Izenberg chronicles Doby’s journey from his birth in South Carolina through his formative years in Paterson, New Jersey (where he was a multisport high school star) to his longtime marriage to high school sweetheart, Helyn Curvy. There was time spent in the United States Army during World War II and four seasons in the old Negro Leagues.

Then Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck – a decent man with a strong sense of social justice – signed Doby to a contract, and the next stage of Larry’s journey began.

Jackie Robinson was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown in 1962. The culmination of Izenberg’s book is Doby’s long overdue induction in 1998.

“When it looked as though I’d never get here,’ Doby told Izenberg after they toured the Hall of Fame Museum together on the night before his induction ceremony, “I used to tell myself it didn’t matter. But tonight I realize how much it means to me.”

Doby and Robinson had comparable major league career statistics. Robinson had a higher batting average (.313 to .283). Doby had the edge in home runs (253 to 141) and RBIs (970 to 761). But as Izenberg notes, “At the end of their careers, a peculiar form of perception widened the gap between Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby on their way to the history books. Each endured the same humiliations. Each emerged as a superstar. But the nation’s memory of Doby began to shrink. The perceived divide between the two grew even wider. It morphed into a conviction that the breaking of the National League’s color line by Robinson dwarfed the breaking of the American League’s color line by Doby. After all, once Jackie did it, it was done. No problem. No story. Right?”

Larry Doby is worth learning about. And Jerry Izenberg is an ideal teacher.

—

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – MY MOTHER and me – is an intensely personal memoir available at Amazon.com. https://www.amazon.com/My-Mother-Me-Thomas-Hauser/dp/1955836191/ref=sr_1_1?crid=5C0TEN4M9ZAH&keywords=thomas+hauser&qid=1707662513&sprefix=thomas+hauser%2Caps%2C80&sr=8-1

In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds