Featured Articles

What about Claressa Shields?

Colbert knows what rates. He had Claressa Shields on Sept. 25. But to be real, there probably should have been more of a hubbub surrounding Shields' gold medal, and her skills. She deserves better, and more.

Colbert knows what rates. He had Claressa Shields on Sept. 25. But to be real, there probably should have been more of a hubbub surrounding Shields' gold medal, and her skills. She deserves better, and more.

It’s Saturday night, and not just any. Tonight is fight night at the McCarson household. My wife and I have the popcorn and drinks ready, and we’re sitting on the couch. We’re watching Andre Ward fight Chad Dawson on HBO. It’s one of the biggest fights of the year, and it’s on regular HBO, not PPV.

All is right in the boxing world.

During the telecast, HBO analyst Max Kellerman says something I agree with. He says Andre Ward is the last American boxer to win a gold medal.

But Max and I are wrong.

My wife turns to me with a look of almost-horror on her face. I wonder if I’ve spilled something on the couch or said something stupid, but no, it’s what Max said.

“What about Claressa?” she says. And she’s right. What about Claressa?

I see from Twitter that Claressa is thinking the same exact thing. I don’t know Kellerman personally, but having been around him a few times at fights, I know enough to think he didn’t mean it that way. Kellerman is the type of guy who talks and takes pictures with fans for as long as they want him to be there. He smiles and seems genuinely interested in what people have to say to him when they talk, and he doesn’t hurry off when he’s approached by someone. He makes eye contact, smiles and chats it up with them like it matters, because he knows it does.

He’s just made a mistake.

The two connect and Max apologizes to her. He says it’s his mistake, congratulates her and tells her she’s made everyone proud. The only problem is that he says this to her via Twitter where only a few people can see, and what he said on HBO that night was to millions of fight fans who might not have been sitting next to someone like my wife to let them know he’s wrong – we’re wrong.

Max and I are wrong because we operate under that same stodgy old paradigm that’s been in place for years: it’s had its moments, but for the most part, women’s boxing is just a sideshow.

Life Goes On

Honestly, I never really think about the series of events again until I’m talking to Claressa this week. I set up an interview with her publicist and make the call. She answers herself, probably tired after a long day from being at school. She’s a senior at Flint Northwestern High School in Michigan, just a kid really. Over the summer, she carried on her shoulders the hopes and dreams of women everywhere, but now she’s back to carrying normal things like school books.

For some reason, I’m nervous talking to her.

I ask Claressa what it’s like being an Olympic champion. I’ve talked to all sorts of fighters and sports figures before, but never a reigning gold medalist and most certainly not one as important as her.

“When you first win the gold medal, it’s so special,” she tells me. “It was my dream for so many years, and now I’ve accomplished my dream.”

It’s always nice to hear stories like this, so I’m genuinely excited to listen to it firsthand. But then she continues.

“Then, for like a week or so, I was like ‘what’s next’?” she says. “You know, after having the same dream so many times and then one day you lay down and you have the same dream but you wake up and you’ve got the gold medal wrapped around you, you get to thinking…why I am still having that dream? I already made it a reality, you know?”

It is at this point I start to think about Kellerman and that look on my wife’s face. Claressa keeps talking.

“I’ll definitely continue boxing,” she says. “The Olympics were just the first step. I still feel like I need to get my recognition. You know? I felt like I would get more recognition because I’m seventeen and I won the gold medal, but I didn’t.”

The knife begins to go in, but I don’t really feel it yet.

“It just seems like a women’s gold medal isn’t as valuable as a man’s gold medal. I don’t know…”

It is at this point that it hits me. We’ve failed her. I’ve failed her. Max has failed her. We. Have. All. Failed. Her.

Claressa comes from some rough stuff. She’s endured it, and she’s come out a better person for it. She’s only seventeen, but she’s wise in the way people who have to crawl from the bottom to the top are, and besides, nobody with the nickname “T-Rex” let’s little things like recognition get them down. If she did, she would’ve never started boxing in the first place.

Claressa’s father, Clarence Shields, was an amateur fighter nicknamed “Cannonball” because of his fast, hard punches. When Claressa first asked her dad if she could learn to box, he told her boxing was a man’s sport. Max and I would have probably told her the same thing; I know I probably would have. But Claressa kept at it anyway until, at eleven years old, her father finally gave in to her, thinking she’d surely get beat up and quit.

She didn’t.

“I’m not really the type of person to think ‘oh I wish I had this, oh I wish I had that’”, she says. “I just accept what I have and just make the best out of it.”

Claressa is a fighter.

A Real Boxer

Claressa is old school tough. She watches fight films of the greats and she emulates them. She considers herself a mash-up of Joe Louis and Ray Robinson. She tells me during one of her first matches in London, she heard someone compare her to Sylvester Stallone’s fictional movie character, Rocky Balboa.

This offends her.

“Someone called me Rocky Balboa!” she says. “In my first fight at the Olympics, I was throwing a lot of punches…I was like…that’s an insult! He’s not even a real boxer. I was like NO, I do not box like him!”

Claressa tells me that in her first fight, her opponent’s strategy forced her to throw wider punches than normal. She says she knew she could land her hook, but in the first couple rounds she was missing by a few inches here and there, so she just kept throwing it. In the rest of her fights, she says she got back to what she does best.

“I was throwing wide punches [in that fight] but the next day, I was throwing sharp punches which is how I usually box,” she says. “I make them miss, and then I make them pay! That’s when you can see how much skill I have.”

Claressa says she looks up to the old school fighters and this doesn’t surprise me. She says she watches tapes of her idols, Joe Louis and Ray Robinson, the most, and that she has The Brown Bomber’s powerful left hook and a sweet, straight right like Sugar’s.

I tell her I’ve heard her compared to Marvin Hagler, and she laughs almost giddily and says what anyone would say to something like that.

“He was pretty good, too!”

A Brave New World

There has never been a Claressa Shields before. She’s new territory in boxing. Sure, we’ve had women boxers before, but we’ve never had a seventeen-year-old gold medalist who grows up immersed in the sport’s amateur ranks like she’s been. We’ve not had a girl who watches black and white film of the best fighters ever and then puts what she sees to use.

Claressa didn’t have someone like her to look up to, either. No one did. I ask her if she truly understands who and what she is, and what she’ll forever be to every girl who ever grows up in the United States wanting to be a boxer.

“It’s very special to be looked at as an inspiration,” she says, but she says it in a way that doesn’t give me the impression we’ve helped her understand how important she really is. This is where Max and I (and you) come back in.

You see, boxing is for everyone, and it’s at its very best when it combines the truth of tough, gritty and skilled competition with the mythologizing poetry of storytelling. It’s not that we make them to be more than they really are, rather we describe them in the most honest way we can. Gods of War, as Springs Toledo calls them, the best of the very best.

Claressa deserves to be part of that.

Her narrative is one of newness and hope. It’s something rare and unbelievable. It’s different. It’s special.She’s a pioneer of a sport that’s been around for centuries. She’s Amelia Earhart. She’s Jackie Robinson. She’s Billy Jean King. She’s Jack Johnson.

What about Claressa? Let’s give her the credit she’s due. She deserves it. It’s says something about us, the boxing community, that she hasn’t gotten it, and it’s something I don’t like. Let’s be better than that. Let’s rally around Claressa and all the other women who want to be treated as real fighters. Let’s make Claressa the show, not the sideshow. Let’s demand Golden Boy Promotions, Top Rank and Main Events start beating down her door to sign her the way they would’ve a man. Let’s demand Everlast and Grant to fight each other for her endorsement. I want her on the cover of Ring Magazine. I want Monday columns from BWAA members about her. Dan Rafael should be buddying up to her on Twitter, and Jim Lampley should be prepping for his extensive interview with her on HBO’s next installment of “The Fight Game.”

Boxing should take care of its own.

For now, Claressa has no idea what she’ll do next. She says she’s already back in the gym training, and that she’s already got a fight lined up next week in a PAL tournament. She’s a fighter, she says. It’s what she does.

“So I’ve been thinking about the next Olympics,” she tells me. “If I get two gold medals, there’s no way they cannot give [the recognition] to me then, right?”

I am not sure I know the answer to her question, and my heart breaks because of it. So should yours.

Featured Articles

Greg Haugen (1960-2025) was Tougher than the Toughest Tijuana Taxi Driver

Many years ago, this reporter overhead ring announcer Chuck Hull gushing over a young boxer who was fairly new to the professional game. “This kid,” he said, referencing Greg Haugen, “is another Gene Fullmer.”

Hull, who would be inducted posthumously into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, was very familiar with Fullmer, a boxer he greatly admired. The ring announcer had worked two of Fullmer’s title fights, Gene’s 15-round decision over Sugar Ray Robinson in March of 1961 and his 10th-round stoppage of Benny “Kid” Paret later that year.

There was a stylistic similarity between Haugen and Fullmer, but the comparison went beyond that. When the cognoscenti in New York got their first look at Gene Fullmer, they dismissed him as just another good club fighter. It was preposterous to think that one day he would defeat the great Sugar Ray Robinson, and never mind that Sugar Ray’s best days were behind him. (Fullmer and Robinson fought three times. The middle fight was a 15-round draw. Robinson won the first encounter with a vicious one-punch knockout.)

Likewise, even after recording three consecutive upsets in 10-rounders at the Showboat in Las Vegas, Greg Haugen was considered nothing more than a good club fighter. He had a wealth of grit, one could see, but in the eyes of the so-called experts, he was too one-dimensional. It was far-fetched to think that one day he would defeat an opponent as slick as Hector Camacho, but we are getting ahead of ourselves.

Greg Haugen, who passed away last Saturday (Feb. 22) at age 64 in a Seattle-area hospice after a three-year battle with renal cancer, entered the pro ranks after winning Tough Man competitions in Alaska. A native of Auburn, Washington, his first documented fight was in Anchorage. Each of his first five fights was slated for 10 rounds.

Those three upsets were forged against Freddie Roach, Chris Calvin, and Charlie “White Lightning” Brown. Two more fights at the Showboat would follow preceding a date with IBF 135-pound champion Jimmy Paul at the Caesars Palace Sports Pavilion. A protégé of Emanuel Steward, Paul was a product of Detroit’s fabled Kronk Gym.

Haugen was one of the first boxers to cultivate a cult following on ESPN. This owed partly to his attractive young wife and their two daughters, adorable little girls, who appeared on camera a lot as they cheered him on from their ringside seats. That marriage was crumbling when Haugen caught up with Jimmy Paul, but Greg overcame the distraction and captured the title with a hard-earned, 15-round majority decision. According to an Associated Press report, Haugen supplemented his $50,000 purse by getting a $2,000 advance and betting on himself at 4/1 odds.

Haugen lost the title and suffered his first defeat in his first title defense, a 15-rounder with Vinny Pazienza before a rabid pro-Pazienza crowd in Providence, Rhode Island. The “Pazmanian Devil” won five of the last six rounds on all three scorecards to win a unanimous decision, but ended the battle with his face all marked-up. “Many ringside observers, including the majority of out-of-town press, had Haugen the winner,” wrote Boston Globe boxing columnist Ron Borges.

They fought twice more. Haugen recaptured the belt with a wide 15-round decision in the rematch in Atlantic City and Pazienza emerged victorious in the rubber match, winning a 10-round decision. It was a great rivalry. Aggregating the scorecards after 40 bruising rounds, Haugen nipped it 1141-1136.

Between his second and third meetings with Pazienza, Haugen was outclassed by defensive wizard Pernell Whitaker on Whitaker’s turf in Virginia, but Greg’s days as a world title-holder were not over yet.

On Feb. 23, 1991, fighting at 140 pounds, his more natural weight, Haugen became the first man to defeat Hector Camacho, scoring a split decision over the 38-0 Bronx Puerto Rican who was defending his WBO belt. The match at Caesars Palace would have ended in a draw if not for the fact that referee Carlos Padilla docked Camacho a point for refusing to touch gloves at the start of the final round.

For Haugen, a noted spoiler, it was the biggest upset of his career. In the sports books around town, Camacho was as high as a 10-1 favorite.

The rematch in Reno followed a similar tack; it was a very close fight, but Camacho won a split decision and Haugen’s third world title reign, like his first, ended in his first defense.

Haugen returned to Reno the next year where he ended the career of Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini, stopping the former lightweight title-holder and future Hall of Famer in the seventh frame. And then, after defeating two fourth-rate opponents, he was thrust into the fight for which he is best remembered.

Greg Haugen vs. Julio Cesar Chavez at Mexico City’s Azteca Stadium wasn’t a great fight, but it was a great spectacle. The announced attendance, 132,247, broke the record set in 1926 when 120,557 jammed Philadelphia’s Sesquicentennial Stadium for the first meeting between Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney.

Those that were there will never forget it. Ring announcer Jimmy Lennon Jr recalled that there were little fires up in the far reaches of the mammoth stadium where people were cooking the food they had brought. “I remember thinking that this was more of a mass celebration than just a sporting event,” reminisced Lennon Jr who compared the event to Woodstock in a conversation with Bernard Fernandez for a story that ran on these pages.

Haugen goosed the gate by saying that Chavez had built his record, reportedly 84-0, on the backs of “Tijuana taxi drivers that my mom could whip.” Chavez took it personally and, to the great jubilation of the great multitude, he punished the American before taking him out in the fifth round.

Other boxers since then, lacking Haugen’s originality, have also demeaned their opponent’s conglomeration of former opponents as a bunch of Tijuana taxi drivers. The term seems to have supplanted “tomato cans” as a term of derision. So, Greg Haugen’s legacy extends beyond what he accomplished in the ring. He left an acorn in the storehouse of American slang.

After being manhandled by Julio Cesar Chavez, Haugen sheepishly said, “They must have been very tough taxi drivers.” He would have 15 more fights before leaving the sport in 1999 with a record of 39-10-2 with 19 KOs. In retirement, he trained a few boxers but couldn’t keep at it after suffering nerve damage in his left arm working the pads with a heavyweight.

There were undoubtedly some very tough guys in the ranks of Tijuana taxi drivers, but in a conventional boxing match, Greg Haugen would have likely whipped them all. He was nowhere as great as the stupefyingly sappy post-mortem tribute that ran in a small Washington paper, but he was tough as nails.

Greg Haugen is survived by four children – two daughters and two sons — and five grandchildren. Speaking to Kevin Iole, his daughter Cassandra Haugen said, “He was a good man with a huge heart. He came from nowhere and made himself into a champion, but he was always a kind-hearted man and just the best Dad.”

We here at TSS send our condolences to his loved ones. May he rest in peace.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Nakatani, Japan’s Other Superstar, Blows Away Cuellar in the Third Frame

WBO world bantamweight champion Junto Nakatani continued his steady advance toward a mega-fight with countryman Naoya Inoue at Ariake Arena in Tokyo tonight with a third-round stoppage of David Cuellar.

After two nondescript rounds, the 27-year-old, five-foot-eight southpaw stepped on the gas and scored two knockdowns before Canadian referee Michael Griffin waived it off. The first knockdown was the result of combination of body punches. As soon as Cuellar got to his feet, Nakatani was all over him. Another combination, this time upstairs, knocked Cuellar on his rump. Looking very discouraged, he made a half-hearted attempt to beat the count and almost made it, not that it would have mattered as he was a cooked goose. The official time was 3:04 of round three.

Nakatani (30-0, 23 KOs) was making his third title defense. He trains in LA with TSS 2024 Trainer of the Year Rudy Hernandez. It was the first pro loss for Cuellar (28-1) who hails from the Mexican city of Queretaro and was making his first start outside his native country.

Nakatani has indicated an interest in unifying the belt which potentially portends three more domestic fights as all four pieces of the 118-pound title are currently in the hands of Japanese boxers. “Bam” Rodriguez and former pound-for-pound star “Chocolatito” Gonzalez sit a division below him and may also be in his future, but the big money is in a showdown with Inoue, the undisputed 122-pound champion. That match-up, when it transpires, will be the first all-Japanese fight to arouse the interest of casual boxing fans around the world.

Other Bouts of Note

Super bantamweight Tenshin Nasukawa took a massive step up in class and was successful, scoring a unanimous 10-round decision over Jason Moloney. The scores were 98-92 and 97-93 twice.

The 26-year-old southpaw has made great gains since his embarrassing loss to Floyd Mayweather Jr on New Year’s Eve of 2018. In that match, the baby-faced Nasukawa failed to survive the opening round and left the ring crying. Heading in to that match, framed as a 3-round exhibition, Tenshin was reportedly 46-0 as a kickboxer and rated in some quarters as the best kickboxer of all time.

After only five pro fights compressed into 30 rounds, the WBA saw fit to rank Nasukawa at #2. He could have embarrassed the organization (check that; the WBA has no shame) by getting his butt kicked by Moloney, a former world title-holder, but Nasakawa (6-0, 2 KOs) rose to the occasion and scored his best win to date. A 34-year-old Aussie, Moloney declined to 27-4.

The 12-round contest between bantamweights Seiya Tsutsumi and Daigo Higa was a spirited contest that ended in a draw. The scores were 114-114 across the board.

The 29-year-old Tsutsumi (12-0-3) was making the first defense of the WBA title he won with a 12-round decision over Takuma Inoue (Naoya’s brother). Higa, also 29 and now 21-3-2, was a former WBC flyweight titlist.

Tsutsumi had an uphill battle after suffering a bad gash on his forehead from an accidental clash of heads in the fourth round. The hill got steeper after Higa put him on the canvas with a left hook in round nine. But Tsutsumi responded with a knockdown of his own in that same round and finished strong, seemingly doing enough to retain his title.

This was their second meeting. Their first encounter in October of 2020, a 10-rounder on a club show at historic Korakuen Hall, also ended in a draw.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

The Hauser Report — Riyadh Season and Sony Hall: Very Big and Very Small

Larry Goldberg promoted his eleventh club fight card at Sony Hall in New York on February 20, continuing the Boxing Insider series that began in October 2022.

Goldberg is well thought of in boxing circles. Matchmaker Eric Bottjer notes, “Here are some words that I have not heard in connection with Larry: ‘Scam artist . . . Liar . . . Untrustworthy.’ He has a good reputation. That doesn’t equate to success on its own. But it’s good when you’re sitting down with people who might want to work with you.”

That said; the life of a small promoter is hard. Goldberg’s February 20 show is a case in point.

Six fights had been scheduled. But last-minute, chaos reigned. The New York State Athletic Commission refused to clear one fighter because of a troubling MRI. Another fighter pulled out because his father thought that his B-side opponent (who had a (6-17-3 record with 6 KOs by) was “the wrong style.” Then the mother of a third fighter tried to hold Goldberg up for an increase in her son’s purse from $1,200 to $2,000 and the fight disappeared when Larry balked at her demand.

That left three fights. And guess what? It was a surprisingly entertaining card. The fights were more competitive that most club fights. And all six fighters came to win.

Jason Castanon (1-1, 1 KO) vs. Stephen Barbee (0-2, 1 KO by) was the first bout of the evening. Neither man was particularly skilled. But they fought hard and both men had a chance to win. Castanon emerged on the long end of a 39-37, 39-37, 38-38 majority decision.

Koby Khalil Williams (4-0, 3 KOs) vs. Nicholas Isaac (5-0, 4 KOs) was next up.

Williams’s four wins had come against opponents who now have a total of 4 wins in 48 fights. Isaac’s record had been fashioned against opponents who are 9-and-49 with 24 KOs by. The bout was a significant step up for both men. The result was a spirited, six-round action fight with Isaac prevailing on all three judges’ scorecards.

Finally, Avious Griffin (16-0, 15 KOs) squared off against Jose Luis Sanchez (14-4-1, 4 KOs, 1 KO by). Griffin has built his record by fighting opponents with limited skills. Sanchez fit that profile. Both men threw non-stop punches. But Griffin’s were faster, straighter, more accurate, and harder. Sanchez was dropped three times in the early rounds (by a left hook, an overhand right, and a right uppercut). In round five, Griffin appeared to tire a bit. And Sanchez was still there. At that point, the fight devolved into an “I’ll punch you and then you punch me” affair, and it seemed possible that Avious would crumble. But he didn’t. Jose Luis had a lot of heart. He just wasn’t good enough. Griffin regrouped and ended matters on an eight-round stoppage with Sanchez still on his feet.

Avious Griffin

Watching the fights, my mind went back to a conversation I had with Ray Arcel when I began writing about boxing four decades ago.

Arcel (a Hall of Fame legend who trained scores of world champions during his years in the sweet science) told me, “Too many people don’t take pride in what they do. They do just enough to get by, maybe to hold onto their jobs, and that’s all. A fighter can’t be like that.” And Arcel went on to reminisce about a time when four-round preliminary fighters on their way to the gym would look back over their shoulder and see kids following them on the street, offering to carry their gym bag. A fighter would come home and neighborhood children would be sitting on the stoop, looking at him and saying, “Wow, he’s a fighter.”

There used to be glory at the club fight level. Being a good club fighter was an end in itself. Now, for the most part, club fights are regarded as stepping stones for prospects who face off against woefully overmatched opponents. On February 20, Larry Goldberg gave boxing fans three good club fights.

****

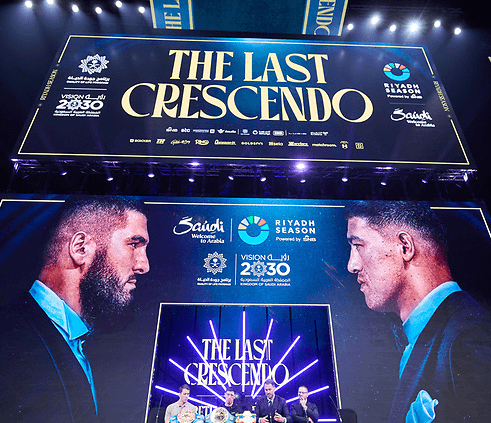

Two nights later, on February 22, the latest Riyadh Season fight card took place in Saudi Arabia. Seven fights of note were on the card, leading the promotion to proclaim that it was “the greatest fight card in the history of boxing.”

It wasn’t. And that was true even before Daniel Dubois and Floyd Schofield pulled out of scheduled title fights due to illness.

You don’t put “the greatest fight card ever” in a 6,000-seat arena (Venue Riyadh Season) when the 25,000-seat Kingdom Arena is next door. Moreover, fight cards are judged in large measure by the main event. And the main event here wasn’t a megafight on the order of Leonard-Hearns I or a half-dozen Muhammad Ali encounters.

That said; it was an exceptionally good card. Credit to Turki Alalshikh for putting it together. Thumbnail sketches of the fights that mattered most (in the order that they occurred) follow.

Callum Smith broke Joshua Buatsi down with a brutal body attack in the middle rounds. Both fighters were hurt as the fight went on. But Buatsi was hurt more and more often. It was a very good fight with Smith prevailing on a 119-110 (which was way out of line), 116-112, 115-113 decision.

Zhilel Zhang vs. Agit Kabayel was an entertaining slugfest with both men evincing a conspicuous lack of upper-body and head movement. After a cautious first round, Kabayel attacked. Zhang, who is 41 years old and has never been in particularly good shape, started fading in round three. Kabayel got sloppy in round four and was dropped by a straight left hand. But Agit went back on the offensive and stopped Zhang with body shots in the fifth stanza.

Vergil Ortiz Jr. vs. Israil Madrimov was a fight that boxing purists were looking forward to. Ortiz is a puncher and wanted to engage. Madrimov didn’t. Israil kept skittering around the ring and Virgil couldn’t figure him out. Then the Energizer Bunny wore down and there were some heated exchanges. That was the fight Virgil (who began scoring big to the body) wanted. Ortiz won a 117-111, 115-113, 115-113 decision.

Carlos Adames vs. Hamzah Sheeraz for Adames’s WBC 160-pound belt had particular significance. Sheeraz (a 5-to-2 betting favorite) is a favorite of Turki Alalshikh who had big plans for him. The belief was that Hamzah would beat Carlos and continue to increase his profile. Meanwhile, Canelo Alvarez’s four-fight deal with Riyadh Season will begin with fights against William Scull and Terence Crawford this year. Then, the thinking went, Canelo would fight the winner of Chris Eubank Jr vs. Conor Benn on Cinco de Mayo Weekend 2026 followed by a fight against Sheeraz on next year’s Mexican Independence Day Weekend.

Adames-Sheeraz was a step-up fight for Sherraz. And he fell short of expectations.

After a cautious first round, Adames began stalking. He couldn’t get past Sheeraz’s jab. Hamzah dictated the distance between them with his jab and footwork. But Sheeraz seemed intimidated and threw few punches of consequence. It was a slow fight. Carlos didn’t silence the crowd. But Hamzah did. The judges ruled the fight a split-decision draw, which meant that Adames retained his title.

Shakur Stevenson vs. Josh Padley was not a good fight. Floyd Scholfield (an 8-to-1 underdog) fell out as Stevenson’s opponent for medical reasons during fight week. Padley, a 30-to-1 underdog. took his place. The typical Shakur Stevenson opponent is slow without much of a punch. Padley is slow without much of a punch. Prior to being called in as a late replacement earlier in the week, he had been on the job installing solar panels. Shakur stopped him in the ninth round.

Then the heavyweights returned to center stage – Joseph Parker vs. Martin Bakole. Parker had been slated to challenge Daniel Dubois for Dubois’ alphabet-soup “championship” belt. But two days before the fight, Dubois pulled out after contracting a viral infection.

Large amounts of money can do wondrous things. When Larry Goldberg lost three fighters during fight week, he was left with a three-bout card. When Dubois was scratched, Turki Alalshikh simply opened his checkbook and brought in Bakole.

Martin was in Africa when he got the call and arrived in Riyadh at 2:00 AM on the day of the fight. Most of us have trouble keeping our eyes open after a trans-continental fight. Bakole had to fight Parker. Moreover, Martin weighed in at a massive 315 pounds, which clearly indicated that he wasn’t in shape (unless one considers round a shape).

Round one saw Parker biding his time while Bakole plodded slowly forward. Two minutes into the second stanza, Joseph landed a glancing right hand off the top of Martin’s head. Bakole went down. He got up. And his corner stopped the fight.

That wasn’t what fans were hoping for. But then they were treated to an exceptionally good fight.

Artur Beterbiev was an 11-to-10 favorite over Dmitry Bivol in a rematch of their October 2024 title-unification bout which Beterbiev won on a close majority-decision. This time, as before, the momentum swung back and forth. But this fight was more intensely contested than their first encounter.

Beterbiev came out hard. He couldn’t reach Bivol, who was circling away and outjabbing him. But Artur was relentless. He started landing and, by the middle rounds, was outpunching and outboxing Dmitry. Then Beterbiev (who at age forty is six years older than Bivol) tired a bit and Dmitry regained control of the contest. Both men were in good condition. Fighting desperately at the end, Artur finished stronger. But this time, the majority decision was in Bivol’s favor.

“What was different?” Dmitry was asked after the fight.

“Just me,” BivoI answered. “I was better.”

****

And a note from the past . . .

In 2004, Tom Gerbasi (who was writing for Maxboxing.com at the time) went to the PAL Gym in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, to record a video interview with Bernard Hopkins while Bernard was training to fight Oscar De La Hoya.

“Hopkins wanted to do the interview while he was getting his hands wrapped,” Gerbasi recalls. “But there was a problem. My camera guy wasn’t there. Hopkins is telling me, ‘Look! I gotta do this now because I have to get my workout in.’ So I interviewed him for twenty minutes while Bouie Fisher was wrapping his hands without my camera guy there. Then Hopkins sparred and went through the rest of his workout. He’s done for the day and getting ready to leave the gym. And finally, my camera guy shows up. He’s very apologetic. He tells us he’s late because he was pulled over by the police and handcuffed because of a bunch of unpaid traffic tickets, which I assume were moving violations. Bernard says, ‘Show me your wrists.’ So my guy shows Bernard his wrists. There were marks from the handcuffs all over them. And Bernard tells us, ‘Okay. Set up the camera.” I did the interview all over again and wound up writing a four-part piece, ten thousand words.”

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – MY MOTHER and me – is a personal memoir available at Amazon.com. https://www.amazon.com/My-Mother-Me-Thomas-Hauser/dp/1955836191/ref=sr_1_1?crid=5C0TEN4M9ZAH&keywords=thomas+hauser&qid=1707662513&sprefix=thomas+hauser%2Caps%2C80&sr=8-1

In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

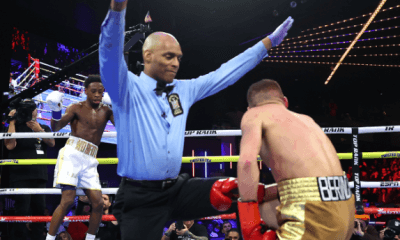

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from Madison Square Garden where Keyshawn Davis KO’d Berinchyk

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoHall of Fame Boxing Writer Michael Katz (1939-2025) Could Wield His Pen like a Stiletto

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

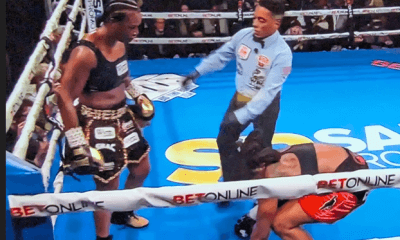

Featured Articles4 weeks agoClaressa Shields Powers to Undisputed Heavyweight Championship

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoBakhodir Jalolov Returns on Thursday in Another Disgraceful Mismatch

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Hopes to Steal the Show on Friday at Madison Square Garden

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoWith Valentine’s Day on the Horizon, let’s Exhume ex-Boxer ‘Machine Gun’ McGurn

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore ‘Dances’ in Store for Derek Chisora after out-working Otto Wallin in Manchester

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoGreg Haugen (1960-2025) was Tougher than the Toughest Tijuana Taxi Driver