Featured Articles

A Look Back at Mayweather-Alvarez: Part One

Now that the dust has settled and there has been time for reflection, it’s worth taking a look back at the boxing event of 2013: the much-hyped, enormously successful promotion known as “The One.”

Budd Schulberg once wrote, “I’ve always thought of boxing, not as a mirror but as a magnifying glass of our society.”

That certainly was true of the September 14th fight between Floyd Mayweather and Saul “Canelo” Alvarez at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

Boxing’s first million-dollar gate was $1,789,238 for the fight between Jack Dempsey and Georges Carpentier on July 2, 1921, at Boyle’s 30 Acres in New Jersey. Adjusted for inflation, that number, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics, is equivalent to $23,377,744 in today’s dollars.

Mayweather-Alvarez came close. The official gate was $20,003,150, which exceeded the previous mark of $18,419,200 set by the May 5, 2007, encounter between Mayweather and Oscar De La Hoya.

The best guess at present is that Mayweather-Alvarez generated 2,200,000 pay-per-view buys in the United States. That would place it second behind De La Hoya vs. Mayweather, which generated 2.45 million buys for a total of $136,000,000 ($153,400,000 in today’s dollars). When all the numbers are in, that $153,400,000 figure is likely to be exceeded by Mayweather-Alvarez.

Mayweather was guaranteed a minimum purse of $41,500,000 to fight Alvarez. That’s more than the entire 2013 player payroll for either the Miami Marlins ($36,341,900) or Houston Astros ($22,062,600). And Floyd’s take is expected to rise significantly once all the pay-per-view buys and other revenue streams are counted.

So let’s take a look at the good and the bad, the fantasy and the reality of Floyd “Money” Mayweather.

It’s starts with Mayweather’s skill as a fighter.

Mayweather seeks to control every aspect of his life. Thus, it’s ironic that his chosen sport is boxing. In baseball, everyone waits for the pitcher. A golfer does what he can do with the laws of physics as his only adversary. Boxing is the hardest sport in the world for an athlete to control.

Over the course of twelve rounds, Mayweather controls the confines of a boxing ring as few men ever have.

The most admirable thing about Floyd is his work ethic and dedication to his craft.

Years ago, Luis Cortes wrote, “A majority of upsets occur when the more naturally-talented fighter forgets that boxing is not just about talent.”

Mayweather doesn’t forget. He gives one hundred percent in preparing for a fight every time out.

“I’m a perfectionist,” Floyd says. “No one works harder than I do. I worked my ass off to get to where I am now. Nobody is perfect, but I strive to be perfect.”

Heywood Broun once wrote of Benny Leonard, “No performer in any art has ever been more correct. His jab could stand without revision in any textbook. The manner in which he feints, ducks, sidesteps, and hooks is unimpeachable. He is always ready to hit with either hand.”

The same can be said of Mayweather. He and Bernard Hopkins have two of the highest “boxing IQs” in the business. Like Hopkins, Floyd shuts down his opponent, taking away what the opponent does best.

“Floyd has man strength and he knows how to use it,” Hopkins says.

When Mayweather is stunned (the last time it appeared to have happened was in round two against Shane Mosley three years ago), he holds on like the seasoned pro that he is. What’s more instructive is what Floyd does when he’s hit solidly but is fully compos mentis. His instinct is to fire back hard rather than let an opponent build confidence.

“Floyd does all things necessary to win a fight,” Mosley notes.

That includes fighting rough and pushing the rules up to, and sometimes beyond, their boundary if the referee allows him to do so.

Against Mosley, Mayweather pushed down hard on the back of Shane’s head and neck as an offensive maneuver seventeen times and used a forearm-elbow to the neck aggressively twenty-three times.

“Winning is the key to everything,” says Leonard Ellerbe (CEO of Mayweather Promotions). “As long as Floyd keeps winning, there’s no limit to the things he can accomplish.”

Mayweather keeps winning. His split-decision victory over Oscar De La Hoya is the only time that a fight went to the scorecards and a judge had Floyd behind. Tom Kaczmarek scored that bout 115-113 for Oscar.

Floyd walks through life with a swagger. He flaunts his lifestyle and wealth. First HBO, and now Showtime, have put tens of millions of dollars worth of time and money into cultivating the Mayweather image. Floyd, for his part, has created and nurtured the “Money Mayweather” persona. “You can’t be a 35-year-old man calling yourself ‘Pretty Boy’,” he said last year, explaining the change in his sobriquet.

When Mayweather speaks of his “loved ones,” one gets the feeling that Floyd holds down the top three or four spots on the list. He lives in ostentatious luxury (a 22,500-square-foot primary residence in Las Vegas and a 12,000-square-foot home in Miami) surrounded by beautiful women and devoted followers who adore him. The money that he puts in their pockets, we’re told, has no bearing on their affection.

Tim Keown has tracked Floyd on two occasions for ESPN: The Magazine and reported, “This is a man who wears his boxer shorts once before throwing them out. This is a man who keeps his head shaved, yet travels on a private jet with his personal barber; who has two sets of nearly identical ultra-luxury cars color-coded by mansion – white in Las Vegas, black in Miami [“roughly two dozen” Rolls Royces, Lamborghinis, Bentleys, Ferraris, Bugattis, and Mercedes].

“Along with gaudy possessions and unlimited subservience comes something far more vital,” Keown continues. “Self-justification. It’s wealth as affirmation. A case filled with more than $5,000,000 in watches is not a mere collection. It is a statement.”

Keown further reported that, on a recent shopping trip to New York, Mayweather spent “close a quarter of a million dollars on earrings and a necklace for his 13-year-old daughter, Iyanna.”

One might question how a gift of that magnitude affects a young adolescent’s values.

Meanwhile, tweets regarding Mayweather’s gambling winnings (he regularly wagers six figures on a single basketball or football game) read like reports of Korean dictator Kim Jong-il’s maiden golf outing, when the Korean state media reported eleven holes-in-one en route to a final score of 38 under par.

Sports Illustrated reported in its March 12, 2012, issue that Mayweather had lost a $990,000 wager on the March 3rd basketball game between Duke and North Carolina. Floyd didn’t tweet that.

Working for Mayweather means being available twenty-four-seven. When Floyd says “jump,” his employees ask “how high?”

“They have to be ready to get up and go at four o’clock in the morning,” Floyd says. “If I call and say ‘I need you now,’ I don’t mean in an hour. I mean now.”

Keown confirms that notion, writing, “His security crew routinely receives calls at two or three a.m. to accompany the nocturnal Mayweather to a local athletic club for weights and basketball. On this day, his regular workout finished, the champ tells one of his helpers to beckon two women from his entourage into his locker room. As he showers, he calls for one of them, a tall, dark-haired woman named Jamie, to soap his back while he continues to carry on an animated conversation with five or six men in the room.”

That leads to another issue. The subservience of women in Mayweather’s world and his treatment of them.

Floyd likes pretty women. No harm in that. He’s on shakier ground when he says, “Beauty is only skin deep. An ugly m——-r made that up.” In late-September 2012, it was reported that Floyd spent $50,000 at a strip club called Diamonds in Atlanta. That’s a lot of money,

More seriously, over the years, Mayweather has had significant issues with women and the criminal justice system. In 2002, he pled guilty to two counts of domestic violence. In 2004, he was found guilty on two counts of misdemeanor battery for assaulting two women in a Las Vegas nightclub. Other incidents were disposed of more quietly.

Then, on December 21, 2011, a Las Vegas judge sentenced Mayweather to ninety days in jail after he pleaded guilty to a reduced battery domestic violence charge and no contest to two harassment charges in conjunction with an assault against Josie Harris (the mother of three of his children). Floyd was also ordered to attend a one-year domestic-violence counseling program and perform one hundred hours of community service.

Was Mayweather chastened by that experience? Did he become more aware of his obligations as a member of society and the responsibilities that come with fame?

Apparently not.

“Martin Luther King went to jail,” Mayweather told Michael Eric Dyson on an HBO program entitled Floyd Mayweather: Speaking Out. “Malcolm X went to jail. Am I guilty? Absolutely not. I took a plea. Sometimes they put us in a no-win situation to where you don’t have no choice but to take a plea. I didn’t want to bring my children to court.”

That theme was echoed by Leonard Ellerbe, who declared on an episode of 24/7, “All you can do is respect the man for not wanting to put his kids through a difficult process. Things are not always what they seem. I have the advantage of actually knowing what the facts are in this particular case. The public doesn’t have this information. I know that he stepped up and did what was needed to do to protect his family.”

Did Mayweather go to jail to protect his children from having to testify at trial? Or did he go to jail to avoid a longer prison term and protect himself from the public spectacle of his children telling the world what they saw?

Either way, Floyd did his children no favors by claiming on national television that they were the reason he went to jail. The children know what they saw on the night that Floyd had an altercation with their mother. If he was taking a bullet for his kids, he should have done so quietly without exposing them to further public spectacle and the taunts of other children telling them in the playground, “You’re the reason your father went to jail.”

One might also ask why Dyson (a professor of sociology at Georgetown University) didn’t confront Mayweather with the fact that Floyd’s confrontation with Josie Harris wasn’t an isolated incident; that there were two previous convictions on his record for physically abusing women.

As for Josie Harris; she was so troubled by Floyd’s denials after his plea of “no contest” to physically assaulting her in front of their children that, in April of this year, she broke a self-imposed silence and told Martin Harris of Yahoo Sports, “Did he beat me to a pulp? No. But I had bruises on my body and contusions and [a] concussion because the hits were to the back of my head.”

Somewhere in the United States tonight, a young man who thinks that Floyd Mayweather is a role model will beat up a woman. Maybe she’ll walk away with nothing more than bruises and emotional scars. Maybe he’ll kill her.

That’s the downside to uncritical glorification of Floyd Mayweather.

Also, as great a fighter as Mayweather is, there’s one flaw on his resume. He has consistently avoided the best available opposition.

A fighter doesn’t have to be bloodied and knocked down and come off the canvas to prove his greatness. A fighter can also prove that he has the heart of a legendary champion by testing himself against the best available competition.

Mayweather has done neither.

Floyd said earlier this month, “I push myself to the limit by fighting the best.”

That has all the sincerity of posturing by a political candidate.

Mayweather has some outstanding victories on his ring record. But his career has been marked by the avoidance of tough opponents in their prime.

There always seems to be someone who Mayweather is ducking. The most notable example was his several-year avoidance of Manny Pacquiao. Bob Arum (Pacquiao’s promoter) might not have wanted the fight. But Manny clearly did. And it appeared as though Floyd didn’t.

Mayweather also steered clear of Paul Williams, Antonio Margarito, and Miguel Cotto in their prime. He waited to fight Cotto until Miguel (like Shane Mosley) was a shell of his former self. Then Floyd made a show of saying that he’d fight Cotto at 154 pounds so Miguel would be at his best. But when Sergio Martinez offered to come down to 154, Floyd said that he’d only fight Martinez at 150 (an impossible weight for Sergio to make).

Thus, Frank Lotierzo writes, “Mayweather has picked his spots in one way or another throughout his career. Floyd got over big time on Juan Manuel Marquez with his weigh-in trickery at the last moment. He fought Oscar De La Hoya and barely won when Oscar was a corpse. Shane Mosley was an empty package when he finally fought him seven years after the fight truly meant anything. As terrific as Mayweather is, he’s not the Bible of boxing the way he projects himself as being. He came along when there were some other outstanding fighters at or near his weight. Yet, aside from the late Diego Corrales, he has never met any of them when the fight would have confirmed his greatness. It would be great to write about Mayweather and laud all that he has accomplished as a fighter without bringing up these inconvenient facts. But it can’t be done if you’re being intellectually honest.”

“Mayweather,” Lotierzo continues, “wouldn’t be the face of boxing today if there was an Ali, Leonard, De La Hoya, or Tyson around. But they’re long gone. Give him credit for being able to make a safety-first counter-puncher who avoided the only fight fans wanted him to deliver [into] the face of what once was the greatest sport in the world.”

Three days prior to Mayweather-Alvarez, Floyd responded to those who have criticized his choice of ring adversaries: “If they say Mayweather has handpicked his opponents; well, then my team has done a f—–g good job.”

Mayweather has a following; those who like him and those who don’t. But whatever side of the fence one is on, it’s clear that Floyd has tapped into something.

“This is a business,” Mayweather says of boxing.

Team Mayweather has played the business game brilliantly. Give manager Al Haymon and the rest of The Money Team credit for maximizing Floyd’s income, making the pie bigger and getting him a larger percentage of it. Through their efforts, Mayweather has become the epitome of what modern fighters strive to be. He has the ability to attract any opponent, determine when they fight, and enjoys the upper hand in any negotiation.

“His ability not only to understand but to capitalize on his value is unrivaled in the sport,” Tim Keown writes. Then Keown references Mayweather’s “singular brand of narcissism, ego and greed,” and notes, “It helps to exhibit an unapologetic brazenness that incites allegiance and disgust in equal measure. Indifference, as any promoter will attest, is hell on sales.”

“Love him or hate him,” Leonard Ellerbe adds, “he’s the bank vault. Love him or hate him, he’s going to make the bank drop.”

Mayweather’s box-office appeal is consistent with other trends in contemporary American culture.

Charles Jay has mused, “There is a constituency that is very attracted to the Mayweather persona. Maybe there is an overlap between that constituency and the one that enjoys the antics of Charlie Sheen.”

Carlos Acevedo opines that Floyd has led “a charmed life inside the ring if a rather charmless one outside it,” and posits, “Being nasty in public under the guise of entertainment is now as American as baseball and serial killers.”

More tellingly, Acevedo argued last year, “Mayweather generates a disproportionate amount of media coverage. Never mind the fact that probably somewhere around six million people in the U.S. saw Mayweather bushwhack Victor Ortiz [and roughly ten million saw him defeat Miguel Cotto]. Compare that, say, to the night Ken Norton faced Duane Bobick on NBC in 1977. That fight, aired on a Wednesday evening in prime-time, earned a 42% audience share, and was estimated to have been viewed by 48 million people. If we want to pretend that more than a few million people care about ‘Money,’ we have to keep listening to penny-click addicts and websites obsessed with celebrity cellulite and tanorexia.”

According to Nevada State Athletic Commission records, all five of Mayweather’s fights between the start of 2009 and mid-2013 (against Juan Manuel Marquez, Shane Mosley, Victor Ortiz, Miguel Cotto, and Robert Guerrero) were contested in front of empty seats. Even with 1,459 complimentary tickets being given away, there were 139 empty seats for Mayweather-Guerrero. More troubling were credible reports that Mayweather-Guerrero registered only 850,000 pay-per-view buys. That’s a healthy number for most fights. But not for a Mayweather fight. And not for Showtime, which had spirited Mayweather away from HBO and entered into a six-fight contract with the fighter that guaranteed him $32,000,000 per fight against the revenue from domestic pay-per-view buys.

Showtime had heavily promoted Mayweather-Guerrero with documentaries, a reality-TV series, an appearance by Floyd at the NCAA men’s basketball Final Four, and numerous promotional spots on CBS Sports television and CBS Sports Radio. Factoring in the cost of production and other outlays, there were estimates that the network had lost between five and ten million dollars on Mayweather-Guerrero. That might have been justified as a “loss leader” to bring Mayweather into the Showtime fold. But it couldn’t be repeated in Floyd’s next fight without speculation that corporate heads would roll.

Mayweather’s fights have been promoted in recent years by Golden Boy, which now has a strategic alliance with Showtime and Al Haymon. The idea that Golden Boy Promotions would crumble once Oscar De La Hoya stopped fighting is now an outdated fantasy. CEO Richard Schaefer has played the promotional game masterfully.

But Golden Boy has little control over Mayweather. According to Leonard Ellerbe, Mayweather Promotions pays Golden Boy to handle logistics on a per-fight basis. “If you run a construction company,” Ellerbe says, “you have to hire someone to pour the cement.”

Schaefer confirms that Golden Boy presents The Money Team with a budget for each fight that includes projected revenue streams and costs (for example, fighter purses, marketing, travel, arena set-up, and its promotional fee).

Showtime could have been forgiven for thinking that guaranteeing Mayweather $32,000,000 a fight for six fights would have entitled it to the most marketable Mayweather fights possible. But there was no such assurance.

After Mayweather beat Guerrero, word spread that the frontrunner in the sweepstakes to become Floyd’s next opponent was Devon Alexander. That raised the likelihood of another sub-one-million-buy Mayweather outing and the loss to the network of another five-to-ten million dollars.

There was little point in Showtime appealing to Mayweather to upgrade the commercial viability of his opponent on grounds that Floyd is a team player. Floyd is a team player as long as it’s Team Mayweather. Thus, Showtime rolled the dice and increased Mayweather’s contractual guarantee to $41,500,000 to entice him to fight Saul “Canelo” Alvarez.

If boxing fans in America have a love-hate relationship with Mayweather, Mexican fans have a love-love relationship with Alvarez. Canelo’s resume is a bit thin. But Mayweather vs. Alvarez on Mexican Independence Day weekend was sure to sell out the MGM Grand Garden Arena and generate a massive number of pay-per-view buys.

Alvarez agreed to a financial guarantee believed to be in the neighborhood of $12,500,000. His purse as reported to the Nevada State Athletic Commission was $5,000,000. But that didn’t include the grant of Mexican television rights and other financial incentives.

The thorniest issue in negotiating the fight contracts was the issue of weight. Mayweather has filled out over the years. He’s now a full-fledged welterweight. But Alvarez fights at 154 pounds.

On May 29th, it was announced that the two men had signed to fight at a catchweight of 152 pounds. Schaefer said that there was a seven-figure penalty should either fighter fail to make weight.

Thereafter, Ellerbe stated publicly that the Alvarez camp had begun the negotiations with an offer to fight at a catchweight and declared, “His management is inept. We take advantage of those kinds of things. They suggested it. Why would we say no and do something different. They put him at a disadvantage, his management did. It wasn’t that Floyd asked for a catchweight because, absolutely, that did not happen. Floyd would have fought him regardless. His management put that out there. So if you have an idiot manager, that’s what it is.”

The Alvarez camp responded by saying that Ellerbe was lying.

“Why would I give up weight?” Canelo asked rhetorically. “I’m the 154-pound champion. When the negotiations started, they wanted me to go down to 147, then 150, then 151, finally 152. I said I’d do it to make the fight. But it’s not right that they’re lying about it. I don’t want to fight two pounds below the weight class, but it was the only way I could get the fight.”

“Being the A-side is about having leverage,” Ellerbe fired back. “We’re always going to put every opponent at a disadvantage if we can.”

Part Two of “A Look Back at Mayweather-Alvarez” will be posted on The Sweet Science tomorrow.

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at thauser@rcn.com. His most recent book (Straight Writes and Jabs: An Inside Look at Another Year in Boxing) has just been published by the University of Arkansas Press.

Featured Articles

Lamont Roach holds Tank Davis to a Draw in Brooklyn

Lamont Roach holds Tank Davis to a Draw in Brooklyn

They just know each other, too well.

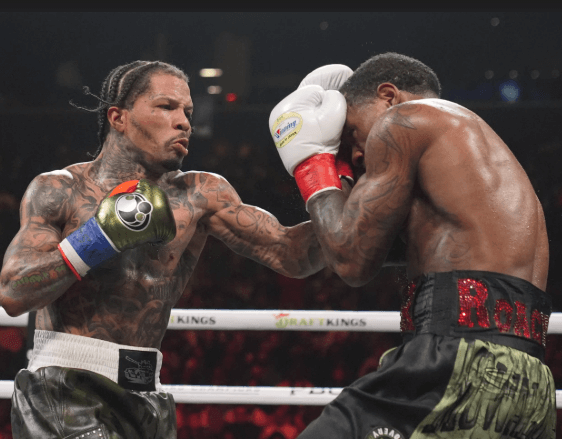

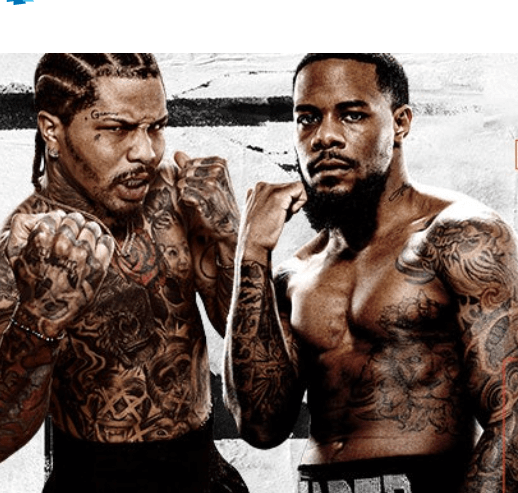

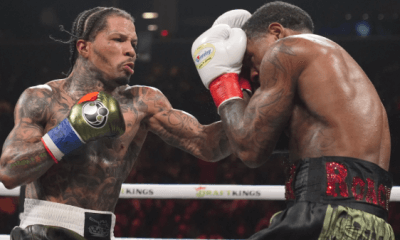

Longtime neighborhood rivals Gervonta “Tank” Davis and Lamont Roach met on the biggest stage and despite 12 rounds of back-and-forth action could not determine a winner as the WBA lightweight title fight was ruled a majority draw on Saturday.

The title does not change hands.

Davis (30-0-1, 28 KOs) and Roach (25-1-2, 10 KOs) no longer live and train in the same Washington D.C. hood, but even in front of a large crowd at Barclays Center in Brooklyn, they could not distinguish a clear winner.

“We grew up in the sport together,” explained Davis who warned fans of Roach’s abilities.

Davis entered the ring defending the WBA lightweight title and Roach entered as a WBA super featherweight titlist moving up a weight division. Davis was a large 10-1 favorite according to oddsmakers.

The first several rounds were filled with feints and stance reshuffling for a tactical advantage. Both tested each other’s reflexes and counter measures to determine if either had picked up any new moves or gained new power.

Neither champion wanted to make a grave error.

“I was catching him with some clean shots. But he kept coming so I didn’t want to make no mistakes,” said Davis of his cautionary approach.

By the third round Davis opened-up with a more aggressive approach, especially with rocket lefts. Though some connected, Roach retaliated with counters to offset Davis’s speedy work. It was a theme repeated round after round.

Roach had never been knocked out and showed a very strong chin even against his old pal. He also seemed to know exactly where Davis would be after unloading one of his patented combinations and would counter almost every time with precise blows.

It must have been unnerving for Davis.

Back and forth they exchanged and during one lightning burst by Davis, his rival countered perfectly with a right that shook and surprised Davis.

Davis connected often with shots to the body and head, but Roach never seemed rattled or stunned. Instead, he immediately countered with his own blows and connected often.

It was bewildering.

In a strange moment at the beginning of the ninth round, after a light exchange of blows Davis took a knee and headed to his corner to get his face wiped. It was only after the fight completed that he revealed hair product was stinging his eye. That knee gesture was not called a knockdown by the referee Steve Willis.

“It should be a knockdown. But I’m not banking on that knockdown to win,” said Roach.

The final three rounds saw each fighter erupt with blinding combinations only to be countered. Both fighters connected but remained staunchly upright.

“For sure Lamont is a great fighter, he got the skills, punching power it was a learned lesson,” said Davis after the fight.

Both felt they had won the fight but are willing to meet again.

“I definitely thought I won, but we can run it back,” said Roach who beforehand told fans and experts he could win the fight. “I got the opportunity to show everybody.”

He also showed a stunned crowd he was capable of at least a majority draw after 12 back-and-forth rounds against rival Davis. One judge saw Davis the winner 115-113 but two others saw it 114-114 for the majority draw.

“Let’s have a rematch in New York City. Let’s bring it back,” said Davis.

Imagine, after 20 years or so neighborhood rivals Davis and Roach still can’t determine who is better.

Other Bouts

Gary Antuanne Russell (18-1, 17 KOs) surprised Jose “Rayo” Valenzuela (14-3, 9 KOs) with a more strategic attack and dominated the WBC super lightweight championship fight between southpaws to win by unanimous decision after 12 rounds.

If Valenzuela expected Russell to telegraph his punches like Isaac Cruz did when they fought in Los Angeles, he was greatly surprised. The Maryland fighter known for his power rarely loaded up but simply kept his fists in Valenzuela’s face with short blows and seldom left openings for counters.

It was a heady battle plan.

It wasn’t until the final round that Valenzuela was able to connect solidly and by then it was too late. Russell’s chin withstood the attack and he walked away with the WBC title by unanimous decision.

Despite no knockdowns Russell was deemed the winner 119-109 twice and 120-108.

“This is a small stepping stone. I’m coming for the rest of the belts,” said Russell. “In this sport you got to have a type of mentality and he (Valenzuela) brought it out of me.”

Dominican Republic’s Alberto Puello (24-0, 10 KOs) won the battle between slick southpaws against Spain’s Sandor Martin (42-4,15 KOs) by split decision to keep the WBC super lightweight in a back-and-forth struggle that saw neither able to pull away.

Though Puello seemed to have the faster hands Martin’s defense and inside fighting abilities gave the champion problems. It was only when Puello began using his right jab as a counter-punch did he give the Spanish fighter pause.

Still, Martin got his licks in and showed a very good chin when smacked by Puello. Once he even shook his head as if to say those power shots can’t hurt me.

Neither fighter ever came close to going down as one judge saw Martin the winner 115-113, but two others favored Puello 115-113, 116-112 who retains the world title by split decision.

Cuba’s Yoenis Tellez (10-0, 7 KOs) showed that his lack of an extensive pro resume could not keep him from handling former champion Julian “J-Rock” Williams (29-5-1) by unanimous decision to win an interim super welterweight title.

Tellez had better speed and sharp punches especially with the uppercuts. But he ran out of ideas when trying to press and end the fight against the experienced Williams. After 12 rounds and no knockdowns all three judges saw Tellez the winner 119-109, 118-110, 117-111.

Ro comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

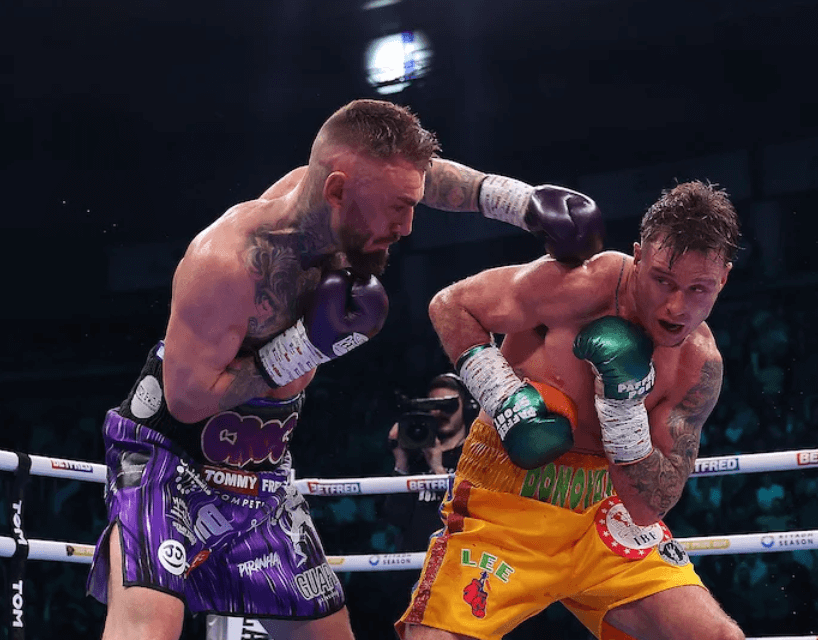

Dueling Cards in the U.K. where Crocker Controversially Upended Donovan in Belfast

Great Britain’s Top Promoters, Eddie Hearn and Frank Warren, went head-to-head today on DAZN with fight cards in Belfast, Northern Ireland (Hearn) and Bournemouth, England (Warren). Hearn’s show, topped by an all-Ireland affair between undefeated welterweights Lewis Crocker (Belfast) and Paddy Donovan (Limerick) was more compelling and produced more drama.

Those who wagered on Donovan, who could have been procured at “even money,” suffered a bad beat when he was disqualified after the eighth frame. To that point, Donovan was well ahead on the cards despite having two points deducted from his score for roughhousing, more specially leading with his head and scraping Crocker’s damaged eye with his elbow.

Fighting behind a high guard, Crocker was more economical. But Donovan landed more punches and the more damaging punches. A welt developed under Crocker’s left eye in round four and had closed completely when the bout was finished. By then, Donovan had scored two knockdowns, both in the eighth round. The first was a sweeping right hook followed by a left to the body. The second, another sweeping right hook, clearly landed a second after the bell and referee Michael McConnell disqualified him.

Donovan, who was fit to be tied, said, “I thought I won every round. I beat him up. I was going to knock him out.”

It was the first loss for Paddy Donovan (14-1), a 26-year-old southpaw trained by fellow Irish Traveler Andy Lee. By winning, the 28-year-old Crocker (21-0, 11 KOs) became the mandatory challenger for the winner of the April 12 IBF welterweight title fight between Boots Ennis and Eimantas Stanionis.

Co-Feature

In a light heavyweight contest between two boxers in their mid-30’s, London’s Craig Richards scored an eighth-round stoppage of Belfast’s Padraig McCrory. Richards, who had faster hands and was more fluid, ended the contest with a counter left hook to the body. Referee Howard Foster counted the Irishman out at the 1:58 mark of round 10.

Richards, who improved to 19-4-1 (12 KOs) was a consensus 9/5 favorite in large part because he had fought much stiffer competition. All four of his losses had come in 12-round fights including a match with Dmitry Bivol.

Also

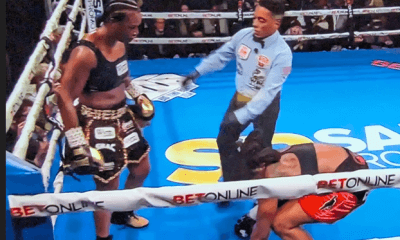

In a female bout slated for “10,” Turkish campaigner Elif Nur Turhan (10-0, 6 KOs) blasted out heavily favored Shauna Browne (5-1) in the opening round. “Remember the name,” said Eddie Hearn who envisions a fight between the Turk and WBC world lightweight title-holder Caroline Dubois who defends her title on Friday against South Korean veteran Bo Mi Re Shin at Prince Albert Hall.

Bournemouth

Ryan Garner, who hails from the nearby coastal city of Southampton and reportedly sold 1,500 tickets, improved to 17-0 (8) while successfully defending his European 130-pound title with a 12-round shutout of sturdy but limited Salvador Jiminez (14-0-1) who was making his first start outside his native Spain.

Garner has a style reminiscent of former IBF world flyweight title-holder Sunny Edwards. He puts his punches together well, has good footwork and great stamina, but his lack of punching power may prevent him from going beyond the domestic level.

Co-Feature

In a ho-hum light heavyweight fight, Southampton’s Lewis Edmondson won a lopsided 12-round decision over Oluwatosin Kejawa. The judges had it 120-110, 119-109, and 118-110.

A consensus 10/1 favorite, Edmondson, managed by Billy Joe Saunders, improved to 11-0 (8) while successfully defending the Commonwealth title he won with an upset of Dan Azeez. Kejawa was undefeated in 11 starts heading in, but those 11 wins were fashioned against palookas who were collectively 54-347-9 at the time that he fought them.

An 8-rounder between Joe Joyce and 40-year-old trial horse Patrick Korte was scratched as a safety precaution. The 39-year-old Joyce, coming off a bruising tiff with Derek Chisora, has a date in Manchester in five weeks with rugged Dillian Whyte in the opposite corner.

Photo credit: Mark Robinson / Matchroom

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 315: Tank Davis, Hackman, Ortiz and More

Avila Perspective, Chap. 315: Tank Davis, Hackman, Ortiz and More

Brooklyn returns as host for elite boxing this weekend and sadly the world of pugilism lost one of its big celebrity fans this week.

Gervonta “Tank” Davis (30-0, 28 KOs), the “Little Big Man” of prizefighting, returns and faces neighborhood rival Lamont Roach (25-1-1, 10 KOs) for the WBA lightweight world title on Saturday March 1, at Barclays Center. PPV.COM and Amazon Prime will stream the TGB Promotions card.

Both hail from the Washington D.C. region and have gym ties from the rough streets of D.C. and Baltimore. They know each other well. I also know those streets well.

Davis has rocketed to fame mostly for his ability to discombobulate opponents with a single punch despite his small body frame. Fans love watching him probe and pierce bigger men before striking with mongoose speed. Plus, he has a high skill set. He’s like a 21st century version of Henry Armstrong. Size doesn’t matter.

“Lamont coming with his best. I’m coming with my best,” said Davis. “He got good skills that’s why he’s here.”

Roach reminds me of those DC guys I knew back in the day during a short stint at Howard University. You can’t ever underestimate them or their capabilities. I saw him perform many times in the Southern California area while with Golden Boy Promotions. Aside from his fighting skills, he’s rough and tough and whatever it takes to win he will find.

“He is here for a reason. He got good skills, obviously he got good power,” said Roach.

“I know what I can do.”

But their close family connections could make a difference.

During the press conference Davis refrained from his usual off-color banter because of his ties to Roach’s family, especially mother Roach.

Respect.

Will that same respect hinder Davis from opening up with all gun barrels on Roach?

When the blood gets hot will either fighter lose his cool and make a mistake?

Lot of questions will be answered when these two old street rivals meet.

Other bouts

Several other fights on the TGB/PBC card look tantalizing.

Jose “Rayo” Valenzuela (14-2, 9 KOs) who recently defeated Isaac “Pitbull” Cruz in a fierce battle for the WBA super lightweight world title, now faces Gary Antuanne Russell (17-1, 17 KOs) another one of those sluggers from the DC area.

Both are southpaws who can hit. The lefty with the best right hook will prevail.

Also, WBC super lightweight titlist Alberto Puello (23-0, 10 KOs) who recently defeated Russell in a close battle in Las Vegas, faces Spain’s clever Sandor Martin (42-3, 15 KOs). Martin defeated the very talented Mikey Garcia and nearly toppled Teofimo Lopez.

It’s another battle between lefties.

A super welterweight clash pits Cuba’s undefeated Yoenis Tellez (9-0, 7 KOs) against Philadelphia veteran Julian “J-Rock” Williams (29-4-1, 17 KOs). Youth versus wisdom in this fight. J-Rock will reveal the truth.

Side note for PPV.COM

Hall of Fame broadcaster Jim Lampley heads the PPV.COM team for the Tank Davis versus Lamont Roach fight card on Saturday.

Don’t miss out on his marvelous coverage. Few have the ability to analyze and deliver the action like Lampley. And even fewer have his verbal skills and polish.

R.I.P. Gene Hackman

It was 30 years ago when I met movie star Gene Hackman at a world title fight in Las Vegas. We talked a little after the Gabe Ruelas post-fight victory that night in 1995.

Oscar De La Hoya and Rafael Ruelas were the main event. I had been asked to write an advance for the LA Times on De La Hoya’s East L.A. roots before their crosstown rivalry on Cinco de Mayo weekend. My partner that day in coverage was the great Times sports columnist Allan Malamud.

During the fight card my assignment was to cover Gabe Ruelas’ world title defense against Jimmy Garcia. It was a one-sided battering that saw Colombia’s Garcia take blow after blow. After the fight was stopped in the 11th round, I waited until I saw Garcia carried away in a stretcher. I asked the ringside physician about the condition of the fighter and was told it was not good.

Next, I approached the dressing room of Gabe Ruelas who was behind a closed door. Hackman was sitting outside waiting to visit. He asked me how the other fighter was doing? I shook my head. Suddenly, the door opened and we were allowed inside. Hackman and Ruelas greeted each other and then they looked at me. I then explained that Garcia was taken away in very bad condition according to the ringside physician. A look of gloom and dread crossed both of their faces. I will never forget their expressions.

Hackman was always one of my favorite actors ever since “The French Connection”. I also liked him in Hoosiers and so many other films. He was a great friend of the Goossen family who I greatly admire. Rest in peace Gene Hackman.

Vergil

Vergil Ortiz Jr. finally made the circular five-year trip to his proper destination with a definitive victory over former world champion Israil Madrimov. His style and approach was perfect for Madrimov’s jitter bug movements.

Ortiz, 26, first entered the professional field as a super lightweight in 2016. Ironically, he was trained by Joel and Antonio Diaz who brought him into the prizefighting world. Last Saturday, they knew what to expect from their former pupil who is now with Robert Garcia Boxing Academy.

Ever since Covid-19 hit the world Ortiz was severely affected after contracting the disease. Several times scheduled fights for the Texas-raised fighter were scrapped when his body could not make weight cuts without adverse side effects.

Last Saturday, the world finally saw Ortiz fulfill what so many experts expected from the lanky boxer-puncher from Grand Prairie, Texas. He evaluated, adjusted then dismantled Madrimov like a game of Jenga.

For the past seven years Ortiz has insisted he could fight Errol Spence Jr., Madrimov and Terence Crawford. More than a few doubted his abilities; now they’re scratching their chins and wondering how they missed it. It was a grade “A” performance.

Nakatani

Japan’s other great champion Junto “Big Bang” Nakatani pulverized undefeated fighter David Cuellar in three rounds on Monday, Feb. 24, in Tokyo.

The three-division world champion sliced through the Mexican fighter in three rounds as he floored Cuellar first with a left to the solar plexus. Then he knocked the stuffing out of his foe with a left to the chin for the count.

Nakatani, who trains in Los Angeles with famed trainer Rudy Hernandez, has the Mexican style figured out. He is gunning for a showdown with fellow Japanese assassin Naoya “The Monster” Inoue. That would be a Big Bang showdown.

Fights to Watch

Sat. DAZN 4 p.m. Subriel Matias (21-2) vs Gabriel Valenzuela (30-3-1).

Sat. PPV.COM 5 p.m. Gervonta Davis (30-0) vs Lamont Roach (25-1-1); Alberto Puello (23-0) vs Sandor Martin (42-3); Jose “Rayo” Valenzuela (14-2) vs Gary Antuanne Russell (17-1); Yoenis Tellez (9-0) vs Julian “JRock” Williams (29-4-1).

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

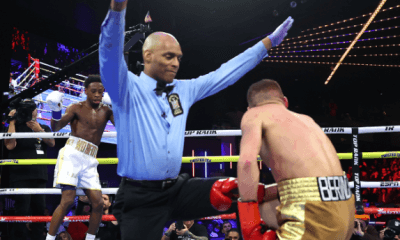

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from Madison Square Garden where Keyshawn Davis KO’d Berinchyk

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoClaressa Shields Powers to Undisputed Heavyweight Championship

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBakhodir Jalolov Returns on Thursday in Another Disgraceful Mismatch

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoGreg Haugen (1960-2025) was Tougher than the Toughest Tijuana Taxi Driver

-

Featured Articles2 days ago

Featured Articles2 days agoLamont Roach holds Tank Davis to a Draw in Brooklyn

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore ‘Dances’ in Store for Derek Chisora after out-working Otto Wallin in Manchester

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Hopes to Steal the Show on Friday at Madison Square Garden

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoWith Valentine’s Day on the Horizon, let’s Exhume ex-Boxer ‘Machine Gun’ McGurn