Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Light-Heavyweights of All Time Part Five – Nos. 10-1

If I have given the impression that I have been a little disappointed in the depth of talent at light-heavyweight, those thoughts can now be banished. Here is a top ten that very nearly put itself together. Harold Johnson drew the short straw and washed up at #11 but him aside there were really no suitors for the top ten that are not ranked within it. Here be dragons.

So listen.

This, is how I have it:

#10 – MATTHEW SAAD MUHAMMAD (49-16-3)

It is both strange and surprising that Matthew Saad Muhammad, born Matt Franklin, has so few in the way of acolytes in this modern era. Muhammad, sometimes, seems to garner less admiration than that which he deserves, despite the fact that he has all the attributes necessary for a fighter to gather fans in excess of his standing.

He’s unquestionably world-class, and proved it against a huge array of talents and styles; he has one of the most compelling backstories in the entire history of boxing (Google if you aren’t familiar with it); and most importantly of all, he was one of the most exciting fighters of his, or any other era. He was like a huge Arturo Gatti with the crucial difference that he tended to hammer his top-ranked foes rather than be hammered by them.

His apprenticeship ended in March of 1977 with a loss to Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, after which he went on a tear through perhaps the most densely packed light-heavyweight division in history.

Matthew Saad Muhammad was matched tough early, and this, combined with either a learned strength drawn from the adversity he experienced in his tragic childhood or an innate toughness born of genetics, meant Muhammad was ready to engage in and emerge victorious from perhaps the most astonishing shootout ever captured on film. Marvin Johnson, a top fifty light-heavyweight in his own right, dug deep to close the class gap he suffered against Muhammad and turn their astonishing 1977 encounter into the most savage brawl ever seen at the weight. Muhammad triumphed after some of the most terrible exchanges in the history of filmed boxing, in the twelfth, leaving the all-but invincible Johnson staggering around the ring like a zombie. The two split just $5,000.

{youtube}UArIOikqodk{/youtube}

Their rematch early in 1979 was another good fight even if it did not quite reach the heights of their first. Muhammad stopped Johnson in eight to lift a light-heavyweight strap. A strap is all he would ever hold. Muhammad never lifted the lineal title, which lay dormant between the departure of Bob Foster and the arrival of Michael Spinks. But Muhammad was the most significant claimant of this time. In addition to Johnson he defeated the excellent Richie Kates in six and twice dispatched the superb Yaqui Lopez in two great fights in eleven and fourteen rounds. John Conteh managed to make the distance in one contest but was slaughtered in four in the rematch; four, too, was the limit for the fearsome Lottie Mwale. Between his 1977 defeat of Johnson and 1981 when the wars caught up with him and Dwight Muhammad Qawi stopped him in ten, he was almost as splendid a light-heavyweight as can be seen.

Almost.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: John Conteh (#29), Marvin Johnson (#27).

#09 – JIMMY BIVINS (86-25-1)

I’m sorry to play the same old tune but…the heavyweights got him.

In the summer of 1943, weighing 174.75lbs, Bivins was matched over fifteen rounds with the lethal Lloyd Marshall, 164.5lbs, for the duration light-heavyweight title, so named because titlists were able to hold their championship only for the duration of time that the champion – in this case, Gus Lesnevich – was in the armed forces. Marshall, as dangerous a fighter of his poundage as there ever was, and perhaps the best super-middleweight to emerge before that weight division, was coming off twin defeats of Anton Chistoforidis and Ezzard Charles and in the form of his life. Bivins was favoured but much credence was given to the rumours that the two had met in sparring some years earlier, a spar that ended when Bivins had to be rescued from Marshall’s tender attentions. It seemed history would repeat itself, as Marshall came out fast in pocketing the first three rounds, provoking a stern reaction from Bivins who dominated the next three; when Marshall dropped Bivins to take the seventh it seemed another corner had been turned, but Bivins picked himself up, shook himself down and won every remaining round up until the eleventh, which seemed a share. A tired Marshall succumbed to a series of lefts topped off with a vicious right to the cheekbone in the thirteenth.

Then Bivins headed north to the heavyweights, where I rank him at #40. His loss to the history of the light-heayweight division cannot be overstated. Bivins was one of the greatest, and head-to-head one of the most dangerous, light-heavyweights in history.

He was never beaten at the weight. A clutch of heavyweights defeated him while he was weighing in under 175lbs, but that does not concern us here. Anton Christoforidis bested him at middleweight – but in his prime years of 1941, 1942 and 1943, spent almost exclusively at and around the light-heavyweight limit, Bivins ran 14-0 against other light-heavyweights. The level of competition he bested was extraordinary.

In 1941, he defeated, among others, the great Teddy Yarosz, the deadly Curtis Sheppard and Nate Bolden. In 1942 he defeated former middleweight strapholder Billy Soose, reigning light-heavyweight champion Gus Lesnevich (in a non-title fight) and future champion Joey Maxim. In 1943, he dropped the legendary Ezzard Charles seven times on his way to a ten round decision victory; former champion Anton Christoforidis over fifteen rounds; and the deadly Marshall.

For those keeping score, that is a little better than a champion a year, more if you allow middleweight title claims. Bivins was a wrecking machine at 175lbs. He was monstrous.

He did great work at heavyweight too, but that work concentrated at the lighter poundage would have made one of the very greatest 175lb careers.

Of course the #9 slot is nothing to be sniffed at – but one of the many areas where light-heavyweight is marked different from heavyweight is the distinctive differences between the #3 slot and the #9 slot. Probably the former was not out with Jimmy’s grasp. The latter, he very much earned.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Anton Christoforidis (48), Gus Lesnevich (39), Joey Maxim (33), Lloyd Marshall (18), Ezzard Charles, (Top Ten).

#8 BOB FOSTER (56-8-1)

A heavyweight a year beat the tar out of Bob Foster up until his 1965 dull but one-sided loss to Zora Folley. Earlier, thrashings at the hands of Ernie Terrell and Doug Jones convinced him, I think, that light-heavyweight was the division for him. The result was one of the greatest title-runs in light-heavyweight history.

This was despite the fact that champion Jose Torres was less than keen on meeting him in the ring. When middleweight legend Dick Tiger stepped up to light-heavyweight, Foster smelled his chance. Tiger had, as he saw it, been frozen out of the middleweight title picture before moving north and had the will and heart to step in with any man. When Tiger retained in a rematch with Torres and Foster blasted out the superb Eddie Cotton in just two rounds, the fight was imminent.

Foster summarised his stylings beautifully after his destruction of Cotton as “jab, jab, jab, then wham!” This sounds too basic to be true of a legitimate all-time great, but it is the essence of Foster’s strategy. Technically proficient without being a true technician, he was gifted with height and reach but took true advantage of neither, fighting in a strange crouched posture that undervalued his 6’3 frame. The point was, Foster wanted to make his opponents hittable. Whether that was through controlling them with his world-class jab to create openings or through initiating exchanges out of which he always – always – emerged victorious, making punching opportunities was the key to his style. This is because Foster is, perhaps, the hardest p4p puncher in the history of boxing.

That point is arguable, but it is also true that those arguments mean little. The truly great punchers are not survivable. Debating who was the more deadly puncher pound-for-pound between Bob Foster and Sam Langford is a little like arguing about what kind nuclear warhead will leave you more deceased. The handful of punchers that lie at the absolute top of the power tree hit people and those people fall asleep.

Tiger fell asleep when he put the title on the line against Foster. Tiger hadn’t been knocked out in ten years of title fights; Foster knocked him out completely. Unaware that he had visited the canvas Tiger spoke only of darkness and silence. The reign of terror had begun.

Foster’s level of competition is sometimes criticised and in this type of company you can understand why. It is true that his was not an era that provided great opposition, but interestingly there were granite chins in abundance. Chris Finnegan had been stopped before, on cuts – but the devastating one-two Foster laid him low with saw him counted out, lurching in the ropes, his brave attempt at Foster ending in a disaster for his brainstem. Frank DePaula was stopped just twice in his career, but Foster turned the trick in a single round with a crackling right uppercut. No softening his man up; no wearing his man down – when he lands, it’s over. Henry Hank lost thirty-one fights in his career but Foster was the only fighter able to stop him. Mark Tessman was stopped only once by concussion and that concussion was inflicted by Foster’s punches. “Punch resistance” was a meaningless phrase for any light-heavyweight that shared the ring with Foster. The only way to survive was to avoid being hit.

Foster lost to a 180lb Mauro Mina when he was 11-1. No other light-heavyweight defeated him. He was 15-0 in title fights. His reign lasted seven years. While Bivins and Muhammad defeated far and away the better opposition, Foster’s total dominance of the division and my sneaking suspicion that Foster would have poleaxed even those great men, sees him sneak in here ahead of both.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: None

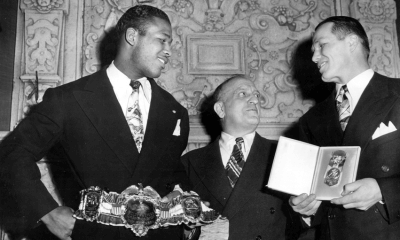

#07 – JOHN HENRY LEWIS (97-10-4)

John Henry Lewis met Maxie Rosenbloom on four separate occasions and the end result was 2-2. But in the two matches that Lewis lost, the men weighed in as heavyweights; Lewis tipped the scale at 182 and 186lbs respectively. When these two elite light-heavies met nearer the light-heavyweight limit, there was only one winner and that was Lewis. What surprises here is that Maxie Rosenbloom was the light-heavyweight champion of the world for these two ten-round non-title meetings, and that John Henry Lewis was a teenager. In fact, he was still at high-school. It didn’t stop him dropping Rosenbloom with a right to the jaw in the first and a left to the kidney in the second in their second meeting in the summer of 1937. Dominating the incumbent champion and then dealing with school the very next day marked Lewis out as something special as he had always been marked out as something special. He first pulled on the gloves as a toddler. He turned professional as a middleweight aged just seventeen. And although he had to wait two years after first defeating Rosenbloom to get his hands on a world champion in a title fight, when he did so he didn’t miss that chance, out-pointing Bob Olin (who had taken the title from Rosenbloom a year earlier) over fifteen in October of 1935. Lewis had already beaten Olin; and Tony Shucco and Young Firpo and Lou Scozza and Rosenbloom. His resume, before he even came to the title, was excellent. Over the coming years he would turn it into something truly extraordinary.

His first defence was staged against #2 contender Jock McAvoy. Lewis, still just twenty-one years old, turned in a performance great maturity and ring-craft, jabbing and counter-punching his way to a decision booed by the crowd for its efficiency rather than any sense that McAvoy had been cheated. Len Harvey, the British and Commonwealth champion was next for a tilt at the title, but before travelling to London to master him, Lewis found the time to dust off Tony Shucco, Al Gainer and former strapholder Bob Godwin, his level of competition remaining outrageously high.

His next defence was a little softer, granting faded ex-champion Bob Olin the rematch he craved and putting him away in eight rounds. “He is the perfect boxer…the best boxer in the world,” Olin later said of his old foe. “He’s fast on his feet with full knowledge of all the scientific departments of the game.” Presumably Emilio Martinez would have agreed with him, succumbing in four rounds, before the perennially ranked Al Gainer pushed him harder over fifteen late in 1938. A late rally protected his title and ensured that he would retire the undefeated light-heavyweight champion of the world. Lewis didn’t just go unbeaten as champion though; he went undefeated at 175lbs. He was never beaten in a match made within 5lbs of the light-heavyweight limit. He was invincible there, dominating a tough era with speedy boxing, a superb left hand and an innate toughness that was only ever beaten from him by heavyweight champion Joe Louis, who stopped him for the first and only time in his career in 1939. Lewis retired shortly thereafter, his eyesight failing him.

One imagines the division let out a collective sigh of relief. Lewis had terrorised it.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Al Gainer (#38), Tiger Jack Fox (#25), Maxie Rosenbloom (#15)

#06 – TOMMY LOUGHRAN (90-25-10; Newspaper Decisions 32-7-3)

A thread has run through this series on the greatest 175lb fighters of all time and that thread is my regular disagreement with history. Whether it’s Sam Langford, the great men of the pre 175lb era generally counted lightheavies by traditionalists or the thorny issues of Billy Conn and Battling Levinsky, I’ve found myself on the rough side of apparent historical truth on numerous occasions. Here, at the sharpest of sharp ends, my trickle of truth finds its way to history’s raging torrent. I add my modest voice to a chorus of more famous names in saying:

Tommy Loughran was one of the greatest pugilists of all time.

Nat Fleischer ranks him at #4, all time, as did legendary boxing man Charley Rose; the IBRO ranks him #6. He appeared at #6, too, on Boxing Scene’s top twenty-five and that is where he is ranked here. This kind of greatness lies on a distant shore and Loughran inarguably belongs there. Simply put, it is impossible to have a list of ten light-heavyweights without placing Loughran somewhere upon it. He was that special, and he proved it.

He proved it first with his record of note standing at just nineteen years old when he was slung in against the immortal Harry Greb. Loughran lost, inevitably, over eight rounds but he won admirers in doing so and impressed with his performance in the opening two rounds and in a sudden desperate rally in the last. He even managed to cut Greb, who spoke in glowing terms of the prospect.

So Loughran matched Gene Tunney.

Again, he did so over eight rounds in a fight generally held to be a draw in 2015. “Not many boxers could outbox Tunney at this stage of his career,” wrote Tunney biographer Jack Cavanaugh. “But Loughran was one of them.”

This statement is far from inarguable but it bears examination. Tunney was one of the very best boxers of his era and is regarded to this day as one of the finest boxers of all time; Loughran, on the other hand, was a teenager. But he was a teenager with perhaps the most cultured, brilliant left hand in history. I’ll say that again: it is possible that the fighter blessed with a better left than Tommy Loughran is yet to be born.

Whatever the details it is a fact that once Loughran made it out of his teens and into his prime, Gene Tunney took nothing more to do with Tommy Loughran. One man who never shirked a challenge, however, was Harry Greb. Loughran fought Greb on a further four occasions, going 1-1-2, defeating him over ten rounds in October of 1923 in a rough contest from which Loughran emerged with the decision via a stern and consistent body-attack.

Most of the other luminaries of the era fell to him too, including Mike McTigue (from whom he took the light-heavyweight title), Jimmy Delaney, Georges Carpantier, Jimmy Slattery, Young Stribling, Leo Lomski, Pete Latzo, Jim Braddock, at which point, as the reader will be unsurprised to hear, the heavyweights got him.

But not before Loughran had staged the fifth of his six victorious world-title fights against Mickey Walker. This was not just a special fight because Walker was so outstanding but also because readily available film survives. Walker, a nightmare for boxers even up at heavyweight, was handled by Loughran. Mickey’s strategy against his timeless jab was to dip and bulldoze but Loughran just tucks his right hand in behind the former middleweight champion’s elbow, adding a superb body attack to his effortless outside game. So successful is this strategy that Loughran begins to feint with the jab to open up the body, and soon Mickey is moving back; Loughran adjusts, re-arranges his jab, throws it, and opens up Mickey’s body again.

Loughran has no qualms about holding Walker while he hits him, he was no saint, but when Walker dips and lifts driving his head into Loughran’s, chin he makes no complaints. He was a shotgun stylist, a renaissance painter who made art with a surgeon’s blade.

Let’s meet the men who keep him from the top five.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Mickey Walker (#36), Jimmy Slattery (#34), Young Stribling (#23), Jimmy Delaney (#14), Harry Greb (Top 10).

#05 – MICHAEL SPINKS (31-1)

As I wrote in Part Four, when contenders passed Dwight Muhammad Qawi they did so on tiptoe, and holding their breath. He was a monster. Two months before Spinks was to take to the ring with this monster, his common-law wife and the mother of his young daughter was killed in a car accident. Just days before the fight he wept openly in front of members of the press – and on the night of the fight?

Nothing.

No glimmer of emotion. Here was a man in absolute control of himself, a professional.

“I live the life of a fighter. I program myself as a fighter.”

Spinks assumed absolute control in the ring, and when his control was challenged he had the tools to equalise the situation with extreme prejudice. Marvin Johnson challenged him, as Marvin Johnson was wont to do, in March of 1981, directly attacking Spinks, and arguably winning all three of the opening rounds in doing so. Spinks backed up, appraised his man, and then delivered an uppercut so brutal that Johnson was unable to continue in its wake. This is the same Marvin Johnson, it should be remembered, that Matthew Saad Muhammad was unable to lay low with three dozen flush power-punches.

So Spinks could be as destructive as he was brilliant, and he was certainly brilliant. When he got to the ring containing Qawi in March of 1983, at stake, the lineal light-heavyweight championship of the world, not only did he show no fear but he showed that brilliance. He dominated Qawi with his jab, and if that brutal sawn-off shotgun of a fighter had his successes against Spinks, there was only one winner. From distance he crackled jabs around Qawi’s head, and when Qawi drew close he found clubbing right hands from an elevated position and a guard-splitting uppercut that snapped the smaller man’s head back repeatedly.

But most of all he controlled Qawi, he forced Qawi to fight his fight, he forced Qawi to jab with him by making himself unavailable for other punches, with cunning, beautifully judged distancing. Malleable in the extreme, his style appeared to be that of a technician, but he had a disjointed approach to building momentum that left rhythm-breakers useless and made learned skills of no practical value to a certain kind of fighter. There are few clues as to what Spinks will throw next.

This occasionally made opponents cautious and led to boring matches where Spinks neglected to take unnecessary chances and his opponents neglect to take any. But he was as capable of the explosive and unexpected as he was of the prosaic.

He staged four defences of the lineal title he finessed and clubbed from Qawi before abandoning it for the heavyweight division, undefeated at 175lbs. There is no company in which Spinks need bow his head – there are other light-heavyweights in his class, but none in excess of it. In some imaginary light-heavyweight maelstrom of greatness, a division made up of the top ten described here, he would excel – if I were betting a single coin on who would emerge as the champion, I might just put it on Spinks.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Dwight Muhammad Qawi (#21), Marvin Johnson (#27), Eddie Mustafa Muhammad (#32).

#04 – GENE TUNNEY (65-1-1; Newspaper Decisions 14-0-3)

I’m not convinced, entirely, that Gene Tunney belongs above the likes of Michael Spinks and Tommy Loughran. What tipped the balance in the end is their respective paper records. Loughran slipped up a few times. Tunney was defeated just once.

And that defeat could hardly be deemed “a slip up.” Tunney lost to Harry Greb, past his absolute prime but still phenomenally dangerous and on the night of the first of five meetings between the two, Greb thrashed Tunney as brutally as he ever thrashed any man; both boxers and the referee finished the contest covered in Tunney’s blood.

The blood was not blue. Tunney’s beginnings were typically working class. But he would raise himself, partly through boxing, all the way to the summit of what passed for American aristocracy, the walking embodiment of the American Dream. Tunney knew that what the US loved most was a winner – this meant that Tunney had to find a way to do the seemingly impossible: he had to find a way to defeat Harry Greb.

He got his first chance to do so nine months later in Madison Square Garden, the site of his ritual slaughter in the first fight, and the officials thought he did enough – Tunney was awarded a split decision victory over fifteen rounds. The result remains one of the most controversial in boxing history. One time trainer of the legendary John Sullivan and the first chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission William Muldoon named the decision “unjustifiable.” Of twenty-three newspapermen polled at ringside, only four found for Tunney; the New York herald went further than many naming the decision “the most outrageous ever awarded in New York.” It is arguable that Tunney did not, then, achieve an unfettered victory in the first rematch, but in the second rematch, their third fight, at the end of 1923, Tunney achieved victory. In September of 1924 the two boxed a draw in their fourth and final fight at the light-heavyweight limit.

Tunney was a Rolls-Royce of a fighter, beautifully balanced with an exquisite left, a digging right (he scored a sizeable number of knockouts with that punch at the weight), he was a solid body-puncher and a world-class counter-puncher. It was a combination that saw him defeat every light-heavyweight he ever met, bar none, Leo Houck, Battling Levinsky, Fay Kesier, Jimmy Delaney and Georges Carpantier among them.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Battling Levinsky (#27), Jimmy Delaney (#14), Harry Greb (Top 10).

#03 – HARRY GREB (107-8-3; Newspaper Decisions 155-9-15)

I suspect that Harry Greb’s high placement above, even, Gene Tunney, may cause some consternation among readers. The internet is awash with accounts of his thousand-glove attack and his supernatural speed, so allow me, instead, to take a purely statistical approach in defence of Greb’s placement.

There are forty-nine other men listed on this top fifty at 175lbs. Greb beat ten of them. In other words, he defeated 20% of the men on this list – nobody, nobody listed above and nobody listed below come anywhere near this statistically. Nor is it the case that Greb cornered past or pre-prime versions of these men. On the contrary, he fought, for the most part, series with each of them over the course of their careers. He gave Jack Dillon two chances at him, beating him firmly the first time and thrashing him the second; Jack Delaney got a second chance but ran 2-0; Tommy Loughran, who shared Greb’s prime, was rewarded with five shots at the great man and for the most part he was beaten firmly. Battling Levinsky received no fewer than six shots at Greb, mostly in no decision contests and in every one of them the newspapermen in attendance favoured the Pittsburgh man. Harry Greb may have been the most dominant fighter in history, and he did a huge swathe of his best work at light-heavyweight.

As for his losses at 175lbs, despite meeting the highest level of competition of any light-heavyweight in history, they were few and far between and often inflicted in what may politely be referred to as “circumstances.” He met the deadly Kid Norfolk on two occasions, getting the best of him first time around only to find himself disqualified in a second contest marred by brutal fouling by both men – eye-witness accounts almost universally decry the disqualifying of Greb but not Norfolk as ridiculous. As we have seen, Gene Tunney holds a legitimate victory over him, winning their December 1923 contest by most sources, but his victory from February of that year is disputed.

Greb twice defeated Tommy Gibbons within the 175lbs limit, but did also drop a decision to him; Loughran managed to win one out of six against “The Pittsburgh Windmill.” He has three legitimate losses at the weight all against all-time greats listed in the top twelve here, men who he also defeated. In total, he holds wins against seven men from the top twenty.

What is disturbing about Greb’s body of work at 175lbs is that even if you removed for some obscure reason his five most significant wins, he would still be bound to the top twenty by his resume, which would very probably remain superior to that of Matthew Saad Muhammad or Roy Jones. Small for a light-heavyweight and famously a fighter of whom no film appears to have survived, his head-to-head ability is inferred by his overwhelmingly positive results against all-time greats, including those of a very modern appearance, like Tommy Loughran and Tommy Gibbons.

Rather than questioning whether or not Greb belongs in the top three, I submit that his absence from the top two is a better cause for curiosity.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Billy Miske (#44), Jimmy Slattery (#34), Battling Levinsky (#27), Kid Norfolk (#20), Jack Dillon (#19), Maxie Rosenbloom (#15), Jimmy Delaney (#14), Tommy Gibbons (#12), Tommy Loughran (Top Ten), Gene Tunney (Top Ten).

#02 – ARCHIE MOORE (185-23-10)

There’s a two-pronged response to the question as to Greb’s placement outside the top two, and the first part of that answer is “Ancient” Archie Moore, the Mongoose. Of course, he wasn’t always ancient but Moore served his lengthy and extreme apprenticeship in the middleweight division before dual losses to the legendary Charley Burley and the mercurial Eddie Booker sent him scampering north to the light-heavyweight division aged twenty-eight. Holman Williams, one of the true monsters of the Murderer’s Row that haunted Moore, elected to follow him and took from him the narrowest of decisions; Moore showed the determination that would carry him to the absolute outer reaches of what is possible for a fighting man in re-matching Williams and becoming only the second man to score a stoppage over one of the best pure-boxers of that or any other era. Moore, as we recognise him today, had arrived.

He became the second man, too, to score a knockout over Jack Chase, another shadowy destroyer from the absurd depths of the middleweight division that now lay below him, defeated Billy Smith, the monster who dispatched Harold Johnson with a single punch – Moore’s own domination of the great Johnson began shortly thereafter. There were disasters, too – the one round knockout loss to Leonard Morrow, although avenged, is hurtful and there were DQ losses that leads one to question what would become one of the great ring temperaments, but it is a fact that Moore had yet to summit at 175lbs. Arguments about whether or not he would actually improve as a fighter are for another day, but what is inarguable fact is that Moore did not come to the light-heavyweight title until late 1952. He was thirty-six years old.

The key, I think, to Moore’s emergence from a pack of fighters to whom he did not prove his inherent superiority (Charley Burley, Holman Williams, Jack Chase, et al) was his ability, perhaps unparalleled, to mount campaigns at heavyweight and light-heavyweight simultaneously. From almost the moment he stepped up to light-heavy he was making matches, too, north of that weight. Moore was using the heavyweights as a tool, I suspect, to enhance his standing as a light-heavyweight, as well as one by which to procure cash.

Whatever the details, his strategy worked and once Moore finally succeeded in getting his opponent into the ring he did not let him off the hook. Maxim fought with astonishing heart, but it is likely that the only round he won was the fourth, awarded to him by the referee after Moore landed a low-blow. That low blow aside, it was a perfect performance and one of the best title-winning efforts on film. Down the years Moore has somehow become perceived by many as a counter-puncher, a fighter who fought in a shell rather like James Toney, waiting for and then pouncing upon chances created by his opponent’s mistakes. Nothing could be further from the truth. Moore was aggressive, marauding but never cavalier. Maxim, easy to hit but hard to hit clean, was just target practice for the Mongoose. He found the gaps that represented half-chances for other fights and made fulsome opportunities of them. His left hook, as short a punch of its kind as can be seen, became a cover for his step in, an industrial elevator of a punch starting at the hip and terminating – well, anywhere, in a singular swift motion. His sneak right which in the first round was a clipping, careful punch, was, by the end of the fight, a steaming dynamo of a punch and one that left the granite-chinned Maxim reeling. Inside, Moore dominated with sniping uppercuts and a savage two-handed body-attack.

By the end, Maxim was desperate. Chewed upon the inside, stiffened by winging punches on the outside, it is great testimony to his heart that he survived the championship rounds. The reign of the greatest ever light-heavyweight champion had begun.

His reign lasted nine years and spanned ten title fights in which Moore went 10-0. These included his astonishing defeat of Yvon Durelle in which he was battered to the canvas three times in the first round and once more in the fifth; of course he survived, of course he stopped Durelle in the eleventh – he had the heart of a lion and the soul of an antique lighthouse. He was in his forty-fourth year. At the time of his final defence against Giulio Rinaldi, he was in his forty-sixth. Moore did not carry out this miracle, like the astonishing Bernard Hopkins, in an era of universal healthcare for fighters who went out twice a year. He did it in an era during which African-American pugilists spent the night before their latest fight in the barn-loft of a local promoter and went out nine times in a year, as Moore did in 1945.

His astounding longevity in tandem with the greatest reign in light-heavyweight history has him near the very pinnacle of this list. All that keeps him from the #1 spot is his very own demon.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Joey Maxim (#33), Lloyd Marshall (#17), Harold Johnson (#11), Jimmy Bivins (Top Ten).

#01 – EZZARD CHARLES (95-25-1)

Moore didn’t like to talk about Ezzard Charles. He loved to talk about Charley Burley. He often expressed his admiration for Rocky Marciano and Eddie Booker and his dislike of Jimmy Bivins. But he did not talk much about Ezzard Charles.

Telling ghost stories is no fun if you live in a haunted house.

The two met first in the spring of 1946 in a fight which was not particularly competitive. Charles was so much better than Moore that referee Ernie Sesto scored the fight ten rounds to zero in Ezzard’s favour; each of the judges found a single round for the Mongoose. It was skill that did it that night and a jab that Moore must have found himself trying to slip in his sleep.

Almost a year to the day after their first meeting they clashed again. Between their first and second meeting they had defeated, between them, Billy Smith, Jack Chase, Jimmy Bivins, Lloyd Marshall and a clutch of other decent fighters. They were untouchable, but to one another. The rematch was closer, so close that Moore could almost touch the win but the result was a majority decision loss, one judge favouring the draw. The deciding factor was likely a single punch, a left hook to the body which dropped Moore in the seventh and caused him to stall thereafter.

Moore was a giant of a fighter but nothing beat larger or stronger within him than his heart. Inevitably he would seek out a third shot at Charles and inevitably Charles would accommodate him. Here was Moore’s moment and he was determined not to let it slip. He began cautiously, boxing defensively, leading at the beginning of the eighth in the main because Charles had two rounds taken from him due to borderline low-blows, but in that fatal three minutes, he opened up in earnest. He jabbed to Ezzard’s mouth and Charles began to bleed. He whipped over that sneaky left hook to Ezzard’s ear and Charles was staggered. That crackling right-hand whipped through and Ezzard was staggered again.

On the cusp of defeat, Charles rescued himself and sealed his greatness forever. Some will even tell you that what followed was nothing less than the springing of a trap that called for him first to be hit and hurt. The two piece that he landed in desperate retort began with a left hook to the temple but the right-hand that followed was described by Pittsburgh journalist Harry Keck as “seeming to travel a complete circle” before it cracked home on Archie’s chin. It was a punch that Moore later claimed he had not seen, and knew nothing of, except darkness.

So there he stands, Ezzard Charles, close to darkness himself, wide-eyed over the quivering form of a detonated nervous system that will in a matter of moments belong again to Archie Moore, unassailable in his greatness. Three times Moore stepped to him and three times Charles defeated him. In the second and third confrontations this difference was arguably a single punch, the fine line between #1 and #2, no more and no less than that.

For despite Moore’s incredible age-defying title reign, he cannot be placed here above Charles. Imagine for a second what it would mean for Joe Louis had he three times defeated Muhammad Ali. There would be no more arguments about which of these two belongs at the top of the heavyweight tree. It is true that Charles did not achieve all that Moore did in the light-heavyweight division. In the aftermath of his knockout of Moore he was labelled a certainty to receive a title shot but Lesnevich, naturally, ducked. In a sense he can hardly be blamed. The single fight film to have emerged of the light-heavyweight Charles is terrifying. Fast, poised, deadly, with a body attack even more savage than Moore he appears unboxable. A fighter as special as Lloyd Marshall seems a boy to a man.

So inevitably, the heavyweights beckoned for the denied light-heavyweight contender and he excelled there too becoming the heavyweight champion of the world, but not before he had defeated, mostly in a dominant fashion, the great names amassed in the greatest light-heavyweight division, including Teddy Yarosz, former middleweight titlist Ken Overlin, light-heavyweight champion Joey Maxim, light-heavyweight champion Anton Christoforidis, the legendary Lloyd Marshall, Jimmy Bivins, Oakland Billy Smith and a swathe of other contenders.

He did not show the spooky longevity of Moore and nor was he permitted to lay a claim to the light-heavyweight title so many great men would throw aloft before and after him, but he did prove beyond all hope of contradiction his inarguable superiority to Archie Moore. This, in tandem with the other fighters he laid low at the weight, is enough to make him the greatest exponent of the fistic art ever to weigh in at 175lbs.

For those of you who have taken the time to read this series of articles from the first word to the last: I thank you.

Other top fifty light-heavyweights defeated: Anton Christoforidis (#48), Joey Maxin (#33), Llloyd Marshall (#17), Jimmy Bivins (Top Ten), Archie Moore (Top Ten).

Featured Articles

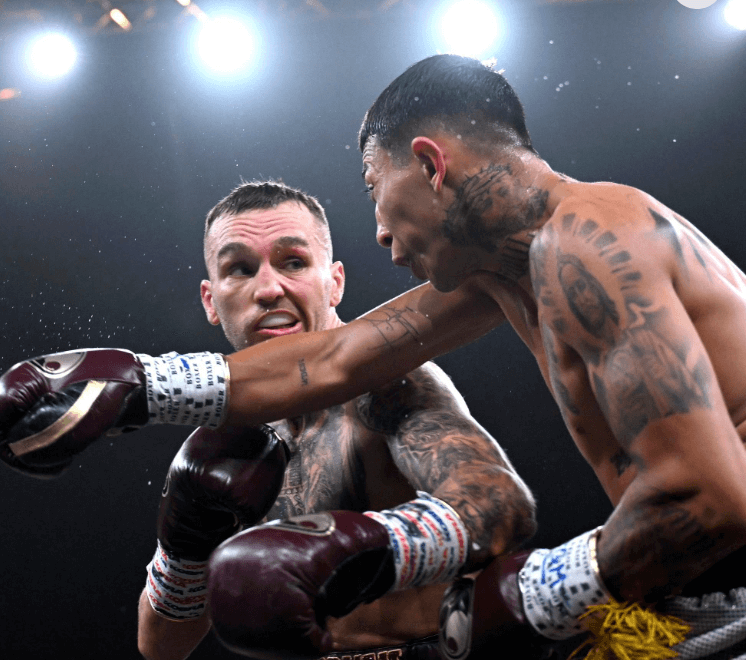

Sam Goodman and Eccentric Harry Garside Score Wins on a Wednesday Card in Sydney

Australian junior featherweight Sam Goodman, ranked #1 by the IBF and #2 by the WBO, returned to the ring today in Sydney, NSW, and advanced his record to 20-0 (8) with a unanimous 10-round decision over Mexican import Cesar Vaca (19-2). This was Goodman’s first fight since July of last year. In the interim, he twice lost out on lucrative dates with Japanese superstar Naoya Inoue. Both fell out because of cuts that Goodman suffered in sparring.

Goodman was cut again today and in two places – below his left eye in the eighth and above his right eye in the ninth, the latter the result of an accidental head butt – but by then he had the bout firmly in control, albeit the match wasn’t quite as one-sided as the scores (100-90, 99-91, 99-92) suggested. Vaca, from Guadalajara, was making his first start outside his native country.

Goodman, whose signature win was a split decision over the previously undefeated American fighter Ra’eese Aleem, is handled by the Rose brothers — George, Trent, and Matt — who also handle the Tszyu brothers, Tim and Nikita, and two-time Olympian (and 2021 bronze medalist) Harry Garside who appeared in the semi-wind-up.

Harry Garside

Harry Garside

A junior welterweight from a suburb of Melbourne, Garside, 27, is an interesting character. A plumber by trade who has studied ballet, he occasionally shows up at formal gatherings wearing a dress.

Garside improved to 4-0 (3 KOs) as a pro when the referee stopped his contest with countryman Charlie Bell after five frames, deciding that Bell had taken enough punishment. It was a controversial call although Garside — who fought the last four rounds with a cut over his left eye from a clash of heads in the opening frame – was comfortably ahead on the cards.

Heavyweights

In a slobberknocker being hailed as a shoo-in for the Australian domestic Fight of the Year, 34-year-old bruisers Stevan Ivic and Toese Vousiutu took turns battering each other for 10 brutal rounds. It was a miracle that both were still standing at the final bell. A Brisbane firefighter recognized as the heavyweight champion of Australia, Ivic (7-0-1, 2 KOs) prevailed on scores of 96-94 and 96-93 twice. Melbourne’s Vousiuto falls to 8-2.

Tim Tsyzu.

The oddsmakers have installed Tim Tszyu a small favorite (minus-135ish) to avenge his loss to Sebastian Fundora when they tangle on Sunday, July 20, at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

Their first meeting took place in this same ring on March 30 of last year. Fundora, subbing for Keith Thurman, saddled Tszyu with his first defeat, taking away the Aussie’s WBO 154-pound world title while adding the vacant WBC belt to his dossier. The verdict was split but fair. Tszyu fought the last 11 rounds with a deep cut on his hairline that bled profusely, the result of an errant elbow.

Since that encounter, Tszyu was demolished in three rounds by Bakhram Murtazaliev in Orlando and rebounded with a fourth-round stoppage of Joey Spencer in Newcastle, NSW. Fundora has been to post one time, successfully defending his belts with a dominant fourth-round stoppage of Chordale Booker.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

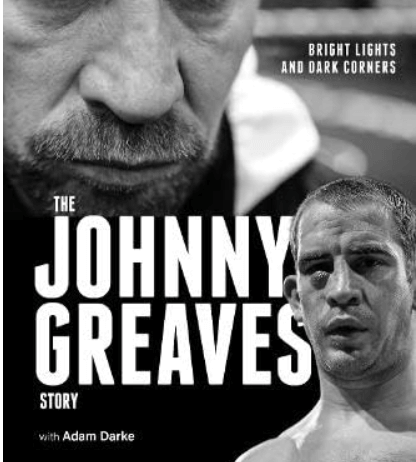

Thomas Hauser’s Literary Notes: Johnny Greaves Tells a Sad Tale

Johnny Greaves was a professional loser. He had one hundred professional fights between 2007 and 2013, lost 96 of them, scored one knockout, and was stopped short of the distance twelve times. There was no subtlety in how his role was explained to him: “Look, Johnny; professional boxing works two ways. You’re either a ticket-seller and make money for the promoter, in which case you get to win fights. If you don’t sell tickets but can look after yourself a bit, you become an opponent and you fight to lose.”

By losing, he could make upwards of one thousand pounds for a night‘s work.

Greaves grew up with an alcoholic father who beat his children and wife. Johnny learned how to survive the beatings, which is what his career as a fighter would become. He was a scared, angry, often violent child who was expelled from school and found solace in alcohol and drugs.

The fighters Greaves lost to in the pros ran the gamut from inept local favorites to future champions Liam Walsh, Anthony Crolla, Lee Selby, Gavin Rees, and Jack Catterall. Alcohol and drugs remained constants in his life. He fought after drinking, smoking weed, and snorting cocaine on the night before – and sometimes on the day of – a fight. On multiple occasions, he came close to committing suicide. His goal in boxing ultimately became to have one hundred professional fights.

On rare occasions, two professional losers – “journeymen,” they’re called in The UK – are matched against each other. That was how Greaves got three of the four wins on his ledger. On September 29, 2013, he fought the one hundredth and final fight of his career against Dan Carr in London’s famed York Hall. Carr had a 2-42-2 ring record and would finish his career with three wins in ninety outings. Greaves-Carr was a fight that Johnny could win. He emerged triumphant on a four-round decision.

The Johnny Greaves Story, told by Greaves with the help of Adam Darke (Pitch Publishing) tells the whole sordid tale. Some of Greaves’s thoughts follow:

* “We all knew why we were there, and it wasn’t to win. The home fighters were the guys who had sold all the tickets and were deemed to have some talent. We were the scum. We knew our role. Give some young prospect a bit of a workout, keep out of the way of any big shots, lose on points but take home a wedge of cash, and fight again next week.”

* “If you fought too hard and won, then you wouldn’t get booked for any more shows. If you swung for the trees and got cut or knocked out, then you couldn’t fight for another 28 days. So what were you supposed to do? The answer was to LOOK like you were trying to win but be clever in the process. Slip and move, feint, throw little shots that were rangefinders, hold on, waste time. There was an art to this game, and I was quickly learning what a cynical business it was.”

* “The unknown for the journeyman was always how good your opponent might be. He could be a future world champion. Or he might be some hyped-up nightclub bouncer with a big following who was making lots of money for the promoter.”

* “No matter how well I fought, I wasn’t going to be getting any decisions. These fights weren’t scored fairly. The referees and judges understood who the paymasters were and they played the game. What was the point of having a go and being the best version of you if nobody was going to recognize or reward it?”

* “When I first stepped into the professional arena, I believed I was tough. believed that nobody could stop me. But fight by fight, those ideas were being challenged and broken down. Once you know that you can be hurt, dropped and knocked out, you’re never quite the same fighter.”

* “I had started off with a dream, an idea of what boxing was and what it would do for me. It was going to be a place where I could prove my toughness. A place that I could escape to and be someone else for a while. For a while, boxing was that place. But it wore me down to the point that I stopped caring. I’d grown sick and tired of it all. I wished that I could feel pride at what I’d achieved. But most of the time, I just felt like a loser.”

* “The fights were getting much more difficult, the damage to my body and my psyche taking longer and longer to repair after each defeat. I was putting myself in more and more danger with each passing fight. I was getting hurt more often and stopped more regularly. Even with the 28-day [suspensions], I didn’t have time to heal. I was staggering from one fight to the next and picking up more injuries along the way.”

* “I was losing my toughness and resilience. When that’s all you’ve ever had, it’s a hard thing to accept. Drink and drugs had always been present in my life. But now they became a regular part of my pre-fight preparation. It helped to shut out the fear and quieted the thoughts and worries that I shouldn’t be doing this anymore.”

* “My body was broken. My hands were constantly sore with blisters and cuts. I had early arthritis in my hip and my teeth were a mess. I looked an absolute state and inside I felt worse. But I couldn’t stop fighting yet. Not before the 100.”

* “I had abused myself time after time and stood in front of better men, taking a beating when I could have been sensible and covered up. At the start, I was rarely dropped or stopped. Now it was becoming a regular part of the game. Most of the guys I was facing were a lot better than me. This was mainly about survival.”

* “Was my brain f***ed from taking too many punches? I knew it was, to be honest. I could feel my speech changing and memory going. I was mentally unwell and shouldn’t have been fighting but the promoters didn’t care. Johnny Greaves was still a good booking. Maybe an even better one now that he might get knocked out.”

* “Nobody gave a f*** about me and whether I lived or died. I didn’t care about that much either. But the thought of being humiliated, knocked out in front of all those people; that was worse than the thought of dying. The idea of being exposed for what I was – a nobody.”

* “I was a miserable bastard in real life. A depressive downbeat mouthy little f***er. Everything I’ve done has been to mask the feeling that I’m worthless. That I have no value. The drinks and the drugs just helped me to forget that for a while. I still frighten myself a lot. My thoughts scare me. Do I really want to be here for the next thirty or forty years? I don’t know. If suicide wasn’t so impactful on people around you, I would have taken that leap. I don’t enjoy life and never have.”

So . . . Any questions?

****

Steve Albert was Showtime’s blow-by-blow commentator for two decades. But his reach extended far beyond boxing.

Albert’s sojourn through professional sports began in high school when he was a ball boy for the New York Knicks. Over the years, he was behind the microphone for more than a dozen teams in eleven leagues including four NBA franchises.

Putting the length of that trajectory in perspective . . . As a ballboy, Steve handed bottles of water and towels to a Knicks back-up forward named Phil Jackson. Later, they worked together as commentators for the New Jersey Nets. Then Steve provided the soundtrack for some of Jackson’s triumphs when he won eleven NBA championships as head coach of the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers.

It’s also a matter of record that Steve’s oldest brother, Marv, was arguably the greatest play-by-play announcer in NBA history. And brother Al enjoyed a successful career behind the microphone after playing professional hockey.

Now Steve has written a memoir titled A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Broadcast Booth. Those who know him know that Steve doesn’t like to say bad things about people. And he doesn’t here. Nor does he delve into the inner workings of sports media or the sports dream machine. The book is largely a collection of lighthearted personal recollections, although there are times when the gravity of boxing forces reflection.

“Fighters were unlike any other professional athletes I had ever encountered,” Albert writes. “Many were products of incomprehensible backgrounds, fiercely tough neighborhoods, ghettos and, in some cases, jungles. Some got into the sport because they were bullied as children. For others, boxing was a means of survival. In many cases, it was an escape from a way of life that most people couldn’t even fathom.”

At one point, Steve recounts a ringside ritual that he followed when he was behind the microphone for Showtime Boxing: “I would precisely line up my trio of beverages – coffee, water, soda – on the far edge of the table closest to the ring apron. Perhaps the best advice I ever received from Ferdie [broadcast partner Ferdie Pacheco] was early on in my blow-by-blow career – ‘Always cover your coffee at ringside with an index card unless you like your coffee with cream, sugar, and blood.’”

Writing about the prelude to the infamous Holyfield-Tyson “bite fight,” Albert recalls, “I remember thinking that Tyson was going to do something unusual that night. I had this sinking feeling in my gut that he was going to pull something exceedingly out of the ordinary. His grousing about Holyfield’s head butts in the first fight added to my concern. [But] nobody could have foreseen what actually happened. Had I opened that broadcast with, ‘Folks, tonight I predict that Mike Tyson will bite off a chunk of Evander Holyfield’s ear,’ some fellas in white coats might have approached me and said, ‘Uh, Steve, could you come with us.'”

And then there’s my favorite line in the book: “I once asked a fighter if he was happily married,” Albert recounts. “He said, ‘Yes, but my wife’s not.'”

“All I ever wanted was to be a sportscaster,” Albert says in closing. “I didn’t always get it right, but I tried to do my job with honesty and integrity. For forty-five years, calling games was my life. I think it all worked out.”

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His next book – The Most Honest Sport: Two More Years Inside Boxing – will be published this month and is available for preorder at:

https://www.amazon.com/Most-Honest-Sport-Inside-Boxing/dp/1955836329

In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

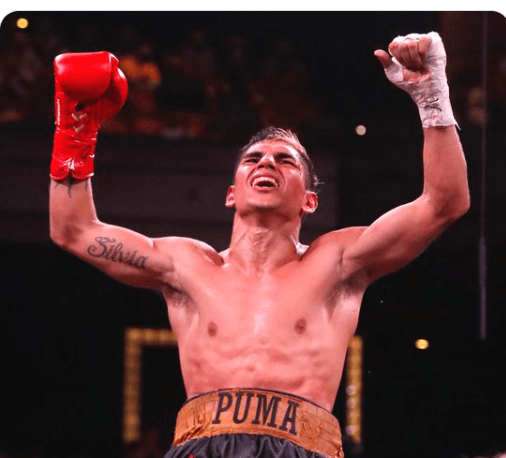

Argentina’s Fernando Martinez Wins His Rematch with Kazuto Ioka

In an excellent fight climaxed by a furious 12th round, Argentina’s Fernando Daniel Martinez came off the deck to win his rematch with Kazuto Ioka and retain his piece of the world 115-pound title. The match was staged at Ioka’s familiar stomping grounds, the Ota-City General Gymnasium in Tokyo.

In their first meeting on July 7 of last year in Tokyo, Martinez was returned the winner on scores of 117-111, 116-112, and a bizarre 120-108. The rematch was slated for late December, but Martinez took ill a few hours before the weigh-in and the bout was postponed.

The 33-year-old Martinez, who came in sporting a 17-0 (9) record, was a 7-2 favorite to win the sequel, but there were plenty of reasons to favor Ioka, 36, aside from his home field advantage. The first Japanese male fighter to win world titles in four weight classes, Ioka was 3-0 in rematches and his long-time trainer Ismael Salas was on a nice roll. Salas was 2-0 last weekend in Times Square, having handled upset-maker Rolly Romero and Reito Tsutsumi who was making his pro debut.

But the fourth time was not a charm for Ioka (31-4-1) who seemingly pulled the fight out of the fire in round 10 when he pitched the Argentine to the canvas with a pair of left hooks, but then wasn’t able to capitalize on the momentum swing.

Martinez set a fast pace and had Ioka fighting off his back foot for much of the fight. Beginning in round seven, Martinez looked fatigued, but the Argentine was conserving his energy for the championship rounds. In the end, he won the bout on all three cards: 114-113, 116-112, 117-110.

Up next for Fernando Martinez may be a date with fellow unbeaten Jesse “Bam” Rodriguez, the lineal champion at 115. San Antonio’s Rodriguez is a huge favorite to keep his title when he defends against South Africa’s obscure Phumelela Cafu on July 19 in Frisco, Texas.

As for Ioka, had he won today’s rematch, that may have gotten him over the hump in so far as making it into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. True, winning titles in four weight classes is no great shakes when the bookends are only 10 pounds apart, but Ioka is still a worthy candidate.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoMekhrubon Sanginov, whose Heroism Nearly Proved Fatal, Returns on Saturday

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 322: Super Welterweight Week in SoCal

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoTSS Salutes Thomas Hauser and his Bernie Award Cohorts

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoGabriela Fundora KOs Marilyn Badillo and Perez Upsets Conwell in Oceanside

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks ago‘Krusher’ Kovalev Exits on a Winning Note: TKOs Artur Mann in his ‘Farewell Fight’

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFloyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The First Boxing Writers Assoc. of America Dinner Was Quite the Shindig

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More