Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Light-Heavyweights of All Time, Part 4 (No. 20-11)

Welcome to the jungle.

Although light-heavyweight surprised with its lack of depth in comparison to say, middleweight, the top twenty is monstrous. The fighters listed between twenty and eleven, in contrast with say, heavyweight, are a monumental threat to the fighters that make up the top ten. What separates the penultimate instalment from the ultimate isn’t necessarily quality of the light-heavyweight but the quality of the light-heavyweight that the fighter defeated, the length of time they spent in the division, or their level of dominance.

At #20 is a fighter who gave Harry Greb some of his toughest fights. At #18 is a stylistic foil so tricky that greater fighters may have succumbed to his deadly counterpunching stylistics; #17 and #16 between them, possibly, could defeat every fighter who will make up the top ten, the first slashing the rhythm of the very best boxers, the second surviving to out-point the deadly punchers. At #13 is a fighter that some people identify as something called the all-time head-to-head pound-for-pound greatest-of-all-time.

You get the point. These are some good fighters.

I hope you enjoy what I have written about them.

#20 – KID NORFOLK (83-23-6; Newspaper Decisions 28-4)

Kid Norfolk (born William Ward) made some decent money in fights in New York in 1921 and just handed it off to a charity that seems to have supported Irish children who didn’t have enough to eat. Four months later he found himself in Pittsburgh ring with the legendary and deadly Harry Greb landing, in the third, a booming right hand that left Greb neatly (if momentarily) deposited on the canvas. Norfolk got the better of the first five rounds of their ten rounder before Greb, being Greb, found his way back, generally being seen as having beaten Kid.

Norfolk and Greb were the same type of man. It was inevitable that they would meet again and when they did in 1924, Norfolk displayed a different side of his character. William Ward gave money to hungry children. Kid Norfolk was one of the most violent and brutal fighters in ring history. He hit Greb low. In the third he butted, or charged him. It was, according to the Pittsburgh Post, “the toughest, roughest, ugliest fight” ever seen. In the fourth the two men butted, hit each other low, elbowed, held and hit their way to the bell for the sixth…and then continued to fight. The referee disqualified Greb, absurdly, awarding the victory to Norfolk although it is not one that is held in any real regard for the purposes of this list.

Fortunately, Norfolk put in work in the light-heavyweight division of the 1920s for all that many of his best wins were earned in the heavyweight division and there is plenty more to recommend him. As well as perhaps the toughest pressure style of a tough era, he smashed Tiger Flowers, who defeated Greb, dominated a series with an ageing Jeff Clarke, gave Battling Siki the beating of his life, thrashed Gunboat Smith in a similar fashion, remorselessly battered Billy Miske and dominated the Jamaica Kid. Norfolk was Dwight Muhammad Qawi in an era better suited to his inherent ferociousness; it is fitting that he slips in here just in front of his descendent.

#19 – JACK DILLON (94-8-15; Newspaper Decisions 93-19-7)

Jack Dillon was the original giant-killer. Short, squat, with a pug’s face vanishing into a thick skull he was built for this kind of work, as a natural a freak as ever boxed. A title claimant at middleweight he was chased from the division by Frank Klaus in 1912, happily visiting it for money fights against name fighters but from the following year he was more likely to be seen tearing his way through the massed ranks of one of the deepest light-heavyweight divisions ever assembled.

Tearing is the right word – Dillon was a vicious and aggressive fighter, astonishing given his habit of giving away poundage to naturally larger men. Dillon, however, was not just a beast but a thinking beast, slippery, clever, difficult to hit clean despite his aggressive, rushing style. It was a terrifying combination and it made him one of the greatest of his era.

Terrifying, too, was his thirst for the ring. He was out thirty times in 1912 and included among his victories was a ten round newspaper decision over Jack “Twin” Sullivan, a light-heavyweight from the last generation who had made heavies sit up and take notice, a symbolic passing of the torch between two light-heavyweights feared by giants.

In 1913 he began his epic series with Battling Levinsky, a defensive genius with a superb left that would trace Dillon’s decline. In six consecutive battles from 1914 through to 1916, Dillon seems to have got the better of his nemesis, winning a mixture of newspaper decisions (in states where official renderings were not permitted) and referee’s decisions, with one draw. In the course of this series, Dillon began claiming the light-heavyweight championship of the world, a claim that today is generally recognised as true; but by the end of 1916, Levinsky had caught up to him and the title both, thrashing Dillon in a one-sided bought in October of that year in what would be their last contest. Dillon is recognised as the victor in their drawn-out series, going 5-2-2

Levinsky had overtaken Dillon only because he had slowed; Billy Miske and Harry Greb were among those to benefit, but still Dillon remained aggressive enough and good enough to dominate the likes of Gunboat Smith and Al McCoy. In his prime, he was a lethal combination of boxing and punching that rarely came unstuck even against the very best.

#18 – VICTOR GALINDEZ (55-9-4)

Victor Galindez fought at the very top of the light-heavyweight division for five long and tough years and lost only twice, to Mike Rossman in September of 1978, avenged, and to the rampant Marvin Johnson in November of 1979. Against this must be weighed the end of his prime and twenty-two victories, over consistently excellent opposition.

One criticism of his performances versus that excellent opposition is that he sometimes scraped home, winning only by the narrowest of margins, and to an extent this is true. When he met the superb Eddie Mustafa Muhammad over fifteen in 1977 he won only by virtue of the brilliant knockdown he scored in the fifth round, slipping and countering an unruffled Muhammad for a count. Galindez didn’t push though and soon the two were swapping rounds again sometimes just a punch between them. Galindez wasn’t bad, but he didn’t dominate, although it was rare to see a fighter do so against Eddie Mustafa Muhammad.

But Galindez was that type of fighter. He had brilliant economy and brilliant judgement. In his fight with Yaqui Lopez that same year, he was left needing to win the final round for the win once again – but he did that. When Lopez got the rematch he felt he deserved the following year, Galindez beat him again and again it was narrow. Watching Galindez though, one feels that he is generally in control of his own fate in these seemingly desperate encounters. Partly this sense is spurred by a sense that such domination would be necessary for his great success; you see Galindez is not really a light-heavyweight.

In terms of poundage, he spent almost his entire career within the range and there is a squatness to his frame that suggests a light-heayvweight’s power and strength packed into a much smaller fighter. At between 5’9 and 5’10 with a reach of just 73” inches he was considerably shorter in both height and length than compatriot and legendary middleweight Carlos Monzon. Everybody he fought was taller than him; everyone he fought outreached him.

He solved these problems with such wonderful elegance that it is easy to forget his stature when watching him box. For example, he rarely led with his jab, the reason being that this punch is almost as dangerous for him to throw as all the others; so he threw the others, showing even experienced opponents something new with a slippery, sliding counter-attack filled with feints and strikes that obeyed different rules to the ones built in the gym.

He missed out on John Conteh, and that hurts him as his status as the best light-heavyweight of the mid-seventies must remain in question, but most of the top men tumbled. I have a sense that had he met Conteh and perhaps Miguel Angel Cuello, a place in the top ten would have been a possibility; as it is he scrapes, barely, into the top twenty.

#17 – LLOYD MARSHALL (70-25-4)

Lloyd Marshall is one of the most fascinating fighters in history. A unique and bizarre style comprised of feints, leaps, sudden unexpected attacks but married to some genuinely technically astute boxing, all of it done with swift surety made him one of the most deadly boxers of the shadowed “Murderer’s Row” which has received so much publicity in the last ten to twelve years. In terms of legacy, Marshall has not profited. Charley Burley has been the poster-boy for that group of marginalised black fighters and I understand why, but Marshall was almost certainly just as good, a fact underlined by his defeat of the lauded Burley.

The injustices inflicted upon both of these men were many, but it is arguably Marshall who suffered more. A crack amateur, financial circumstance demanded he turn professional before the Olympic trials; sleeping under the bleachers at a baseball stadium he fell ill and couldn’t find work. When, finally, his career took off, Marshall found himself cornered by harsh reality and perhaps a certain moral weakness is rumoured to have become what was politely known in the lexicon of the time as a “business” fighter – a fighter paid to take an opponent the distance, or even to lose. While I may have personal suspicions regarding which fights specifically are tainted in this way there is no direct proof and as such these losses are treated as what they are – legitimate losses or possible quit jobs. Either way, Marshall’s “inconsistencies” count against him. Post-war, Marshall slipped badly. 1945 wasn’t an unreasonable year for him with his only two losses coming in hard-fought contests against the great Archie Moore, but by the end of the decade he was wavering dangerously close to becoming just an opponent, a tragedy.

Even more tragic was that Marshall never won the light-heavyweight title, despite the fact that he thrashed two champions in one sided contests. Anton Christoforidis was less than two years removed from his short title reign and had lost, in that intervening time, to only two fighters, Ezzard Charles and Jimmy Bivins. Bivins beat Christoforidis narrowly but Marshall hammered him, letting only two rounds of the ten round fight slip. The other championship victim that Marshall buried was Freddie Mills. Marshall crushed Mills, who was a year removed from the title, stopping him in just five, half the time it took the brutal Gus Lesnevich.

Precious, wonderful minutes of Marshall’s battle with Mills survive. He is a gunslinger of the highest order. Past-prime, hovering on the cusp of irrelevance, he is lethal. His short left-hook, especially to the body, is one of the very best punches of its kind, not just in the light-heavyweight division but in any division. Mills was so befuddled that at least once he appeared to square up to the referee.

Neither one of these wins are Marshall’s best. Marshall’s best win is over Ezzard Charles. Marshall is the only light-heavyweight ever to stop Charles. He dropped him between seven and nine times, stopping him in eight rounds. The fight was not competitive. The fight was another one-sided thrashing.

When Marshall was on he was almost unstoppable. There are too many losses for him to rank among the fifteen best at the weight, but he was probably good enough to test any of them and beat many of them and he beat as many ranked men as any but the quill and the long-standing belt-holders. He beat as many really good ones as almost any of them. Spotted throughout this series of articles are references to the all-time rankings of historians down the years, men who know the sport: not one of them, not a single one of them rates Lloyd Marshall top twenty. Witness:

Ezzard Charles, Nate Bolden, Joe Kahut, Curtis Sheppard, Anton Christoforidis, Shorty Hogue, Teddy Yarosz, Freddie Mills, Holman Williams, Bob Garner (stopped in one), Bob Karner (stopped in one).

There are guys who are routinely ranked above Marshall who never, ever get anywhere near besting this level of competition but appear on both the Boxing Scene list and the IBRO list. Why? Georges Carpentier is on the IBRO list! To be brutally frank, the record of light-heavyweight Lloyd Marshall embarrasses Carpentier’s record at light-heavyweight.

And you can quote me on that.

#16 BILLY CONN (64-11-1)

Seeing Sam Langford ranked in the low twenties was, I’m sure, something of a shock for the traditionalists among The Sweet Science’s readership – my guess is seeing Billy Conn outside the top ten will be an even bigger shock.

As a longtime boxing fan I’m familiar with lists and I’ve come to understand, like you, that criteria are everything. What the listmaker espies as crucial is what defines the standing of a given fighter on any list. Billy Conn appears at #10 on Boxing Scene’s top twenty-five at the weight, the same spot at which he was placed by Herb Goldman; he is in at #9 on the IBRO list. Here, he is lower by several spots and this needs to be explained. The primary difference here is criteria.

My criteria, as stated in the introduction to Part One, are concerned with fights contested at the 175lb limit. As I wrote then, fights “that were fought above the light-heavyweight limit will be considered…a heavyweight contest and will not be credited here.” Furthermore, “the weight class in question is always defined by the heavier fighter. If a 173lb man is fighting a 203lb man he is engaging in a heavyweight contest.” Provision is made for an old-fashioned “over-the-weight” meeting, of course, meaning that a fight between 177lb fighter and a 178lb fighter can still be a light-heavyweight contest – but this rule of thumb extends itself to divisions below, too. Conn, to put it bluntly, is caught in a perfect storm of criteria that inhibits his ranking at this weight.

Conn had no amateur experience and was blasted face first into professional competition in the mid-thirties, as a teenager, breaking into the world-class only a few years later; but he fought then as a middleweight, not a light-heavyweight. It was 1938 before he stepped into the bigger division in earnest and he preferred to do so against old middleweight rival Honey Boy Jones, a clean win in twelve; a decisive victory over journeyman Domenico Ceccarelli followed before a narrow squeeze past Eric Seeling and a raucous, foul-filled loss to old-foe, the 162lb Teddy Yarosz (Conn weighed 168lbs). “Too much Irish” was the call from boxing scribe Regis Welsh in the aftermath, a sentiment typical of the generally indulgent nature of the press when it came to Conn. This loss to Yarosz, however, was the only one Conn ever posted at light-heavyweight; in fact, he went unbeaten over nineteen contests before Joe Louis famously wiped him out in thirteen rounds of their 1941 heavyweight title fight. “What’s the point in being Irish if you can’t be stupid?” was how Conn explained his decision to duke it out with Louis with only minutes to go until he hoisted the title. That was his eighth consecutive battle at heavyweight. His decision to hunt Louis called for him to abandon the light-heavyweight title he had won against Melio Bettina in 1939. He defended against Bettina once more, later that same year, then twice beat Gus Lesnevich, and then he bid light-heavyweight adieu. He revisited it once more, for a fight with reigning middleweight champion Tony Zale (Conn weighed 175lbs), making Zale another in a long line of middleweights that Conn defeated at the weight; Zale joined a 160lb Fred Apostolini and a 166lb Solly Kreiger who had met a light-heavyweight Conn before he came to the title.

Conn enjoyed a size advantage over these men, but they were exceptional middleweights and Conn’s defeat of them at the heavier poundage does speak for him. That said, his adventures in heavyweight in combination with his determination to entertain old-time foes from the middleweight class rather than the ranked light-heavyweights of the era is what hurts him. By my count he defeated only a handful of legitimate 175 pounders.

This, then, is how Conn finds himself lower than is traditionally the case. Still, it is inaccurate to say that this system is hard on Billy – he finds himself ranked at #62 on my heavyweight list, and when the middleweight top fifty rolls around, he will be under consideration for that list, too, despite the enhanced competition.

For what Conn actually did at the weight though, he can’t find himself much higher than he is here.

#15 – MAXIE ROSENBLOOM (207-39-26; Newspaper Decisions 16-4-4)

Everyone beat Maxie Rosenbloom.

Considering only the men who made this top fifty, Joe Knight, John Henry Lewis, Mickey Walker, Tiger Jack Fox, Yong Stribling, Jack Delaney and Jimmy Slattery all owe a debt of gratitude. Many others were placed under consideration specifically because they, at one time or another, bested Rosenbloom: Tiger Flowers, Leo Lomski, Bob Olin, Bob Godwin, Lou Scozza, Tony Schucco, George Manley and Pete Latzo, for example, all hold victories over him. And yet here he is – firmly entrenched within the top twenty. Why?

In part, it is because of this attitude to big business. With the world-title on the line, he was a different beast and one that more often than not emerged triumphant from a skittish, rough, difficult fight. So Joe Knight was able to beat him, comprehensively according to some, in 1932 but come 1934 with the title on the line and Rosenbloom was able to scrape home to a draw and retain his championship. That same year, 1934, Rosenbloom dropped a decision to Mickey Walker over ten in a non-title fight, but the previous year in a confrontation for the championship of the world, Walker had managed to win perhaps as many as three out of fifteen rounds. Bob Godwin managed two draws over ten narrow rounds in his run up to his title-shot at Rosenbloom, but come that night he found himself in the ring with a different fighter, an aggressive, direct one who dropped Godwin twice in the first round and re-opened cuts the challenger had suffered in training to stop him in four.

Hardly a pushover in non-title affairs, he did manage to beat fighters as good as Lou Scozza and Leo Lomski without any gold on the line but it is a fact that he was better with a glittering motivation ringside. Nevertheless his title record is a less than overwhelming 7-1-2, the losses coming against Bob Olin, who dethroned him, and Jimmy Slattery, who repulsed him in his first shot at a title. Thrown in with his inconsistencies of form and occasional dis-interest in combat I can’t rank him at #11 as the IBRO did, or #9, his placement on the Boxing Scene list, but rather bang in the middle of the top twenty, the highest ranked of the division’s flawed geniuses.

#14 – JACK DELANEY (73-11-2; Newsapaper Decisions 2-0-0)

Occasionally, a king-killer comes along and just wipes out that decade’s royalty. A destroyer of champions, he often appears at an era crossroads to vanquish the faded kingpins of the last era and the coming giants of the next; which is to say that luck, usually, plays a part where the king-killer is concerned.

Despite this they tend to be the greatest of fighters; Henry Armstrong is a king-killer; Sugar Ray Robinson, too. Jack Delaney is such a fighter.

His luck came in the form of the timing of his victorious meeting with the great Tommy Loughran who he defeated over ten rounds in 1924 with an inexperienced Tommy listed at just 16-3-1 by Boxrec. But Delaney rematched Loughran the following year, a desperately narrow draw the ruling after some confusion with the scorecards. This makes Jack Delaney, with a record of 1-0-1, the only light-heavyweight in history to have a winning record against Loughran.

Paul Berlenbach, as documented in Part Three, was the major victim of Delaney’s brilliance, but former champion Mike McTigue, having lost his title only ten months earlier to Berlenbach, was another former champion to suffer domination at the hands of Delaney, beaten in just four rounds at a time when his safety first style was infamous. Maxie Rosenbloom, a champion of the future, followed shortly thereafter, dropping a ten round decision to a fighter who was picking of champions of the future and the past with equal appetite.

For these and the lesser tasks he performed in his superb career, Delaney utilised an excellent left hand, surprising, snappy, varied and hard, a crackling right-hand often thrown behind that covering left, fabulous strength often underappreciated but very apparent in the scant footage that survives of his second career up at heavyweight, and most of all an unassailable generalship that drew even brilliant opponents into his fight. More than that, his losses at 175lbs came against Berlenbach (who needed four tries, losing three of them), Jimmy Slattery, king of the six-rounder who twice beat him over that distance, and Young Fischer, who forced a corner stoppage after bouncing an inexperienced Delaney repeatedly off the canvas.

This aside, he often seemed invincible at the weight which made his departure for heavyweight such a great shame; there he was a failure, achieving some decent wins with organisation of his impressive boxing but generally out-gunned by the bigger men he was faced with.

One down, Delaney saw off more kings than almost every fighter to box at light-heavyweight.

#13 – ROY JONES JNR. (61-8)

Thankfully, Roy Jones is lacerating his wonderful legacy as a fighter up at cruiserweight with his determination to continue boxing despite a string of hideous knockout losses; at light-heavyweight we have only to consider his wonderful career between 1996 and 2009, which encapsulates both the searing brilliance of the invincible genius and the crash and burn of boxing’s most mercurial Icarus.

He stepped up from 168lbs where he may, literally, have been invincible, to a light-heavyweight division which probably was a little too big for him. Under 5’11 and with a reach of just 74” Jones was sized for the fifties, not the nineties, the day-before weigh-in allowing larger frames to squeeze into the 175lb weight limit. Of course, it didn’t matter. Jones was so brilliant at his peak that he operated almost independently of his opponent anyway.

Those opponents are the subject of some scrutiny, however, with many claiming that part of Roy’s unearthly appearance was due to the limited competition with which he shared the ring. To get the negatives out of the way, yes, Jones needed Dariusz Michalczewski in order to claim true domination over what was an era lacking true depth. That said, Jones thrashed, mostly in non-competitive bouts, so many contenders ranked by Ring Magazine as to reach double-figures. Of course, The Ring’s rankings are not infallible but the following two statements are fact: only a tiny handful of light-heavyweights of any era defeated ten or more men to have appeared in these rankings, and Roy tended to be in non-competitive bouts with his prey. The main point for me is that for every Glen Kelly there was a Clinton Woods and for every Clinton Woods there was a Virgil Hill.

Hill boxed well in the first round against Jones and he may even have won it. He looked huge in the ring in comparison with Roy and he used his size and that pinging jab to menace him while showing uncharacteristic aggression becoming of a bigger man. Roy studied it, read it, and in round two he timed it. But his timing wasn’t like the timing of Victor Galindez or Lloyd Marshall. In the main, this is because of the handspeed. No opponent could adjust to Roy’s incoming, they just had to absorb those punches; this allowed Jones to hit of such a narrow distance as to make him unfathomable. There was no “solving” him. Beating a prime Jones had nothing to do with defence and everything to do with durability and punching power. In the second, having moved Hill onto him with that double-step shuffle, he dipped to his own left, threw a single jab up the middle to the belly. Hill shaped himself to hit down, Jones extracted himself, moved his upper body around Hill’s outstretched left (the defence) and landed a full-bodied right hand over the top, all before Hill – who was quick – had the time to react to the first punch.

There are perhaps no other light-heavyweights who could have made this small move against Hill. Perhaps a feint to the belly followed by the right but to be honest, the risk probably doesn’t justify the reward. Jones did these things as a matter of course. The flashy combinations are the ones to attract the attention, of course, but it is these less stunning sequences that make him so unboxable. Note that “unboxable” isn’t really a word, but Jones stretches the lexicon (and Hill, who he stopped in the fourth with a titanic bodyshot. It was Hill’s only stoppage loss at the weight).

So why no top ten berth for Roy? Why does he languish below, say, Tommy Gibbons? In part it’s because, like Muhammad, Roy never attained lineage; he needed Michalczewski for that and he decided he had better things to do. That’s fair enough, but it means he can’t be credited as “the man” in this division in the way his fans might wish. Yes, we can suppose he is the best of his era, but it was never proven beyond hope of contradiction. That hurts him.

Antonio Tarver and Glen Johnson hurt him also. Both inflicted dangerous knockouts upon him calling his chin into question for all time. It may be that Jones was hurt by coming down in weight from the light-heavyweight’s bane, a trip up to heavyweight, or it may be that he carried with him a certain vulnerability that lay veiled due to his brilliance.

I seem to have given him the benefit of the doubt here because I’d happily see him below Delaney in terms of what he achieved and opposition bested; my suspicion that Jones would tend to have defeated him and tended to have done better against the field seems to have seen him slip in here at unlucky thirteen.

#12 – TOMMY GIBBONS (57-4-1; Newspaper Decisions 39-1-3)

A look down the list of the opposition belonging to Kid Norfolk will reveal a stunning list of fighters as good as just about anyone to have stepped into the ring. But it was Tommy Gibbons that Kid Norfolk picked out as the single best opponent of his glorious career, a man who “hit me with everything.” Not Harry Wills the monstrous heavyweight that beat him out in two in 1922; not Harry Greb, the intangible legend who, indeed, Gibbons went 2-2 with; not the terrifying Sam Langford who yo-yoed Norfolk off the canvas before stopping him in 1917; Gibbons, who busted him in six rounds in 1924.

Norfolk rated him for his offence but champion Battling Levinsky, one of the busiest fighters in history, ranked Gibbons the best defence specialist he faced – ever. Having been in with Gene Tunney, Young Stribling, Harry Greb and Jack Sullivan among literally hundreds of others, he ranked Gibbons the hardest to hit clean, the cleverest of them all.

If this combination of technically proficient snapping offence and incalculable defence may be thought by the reader to be a hamper to a young fighter’s ambition in getting matches, the reader would be right.

“Every fighter in the country wants to fight Dempsey, but none of them will fight Gibbons,” complained legendary promoter Tex Rickard when Gibbobs began in earnest to stalk the heavyweights. The Pittsburgh Press reported in November of 1924 that Gene Tunney, Harry Wills and Jack Renault, all contenders to Dempsey’s heavyweight crown, all found better things to do when the New York Commission came looking for a name opponent to put in the ring with Gibbons in December of that year. He was feared and he was fearless.

It should be noted that Norfolk was ageing when Gibbons thrashed him, but it should also be taken into account that Gibbons was past his own sweltering prime and just six months from retirement. Norfolk aside, he handed Georges Carpantier a ten-round thrashing, credited by some newspapermen with winning ten out of ten rounds against the plucky Frenchman, but his finest moment came some four years earlier against the great Greb. Although Greb was always small for a light-heavyweight, Gibbons had only weighed in a single pound heavier at 166lbs. Gibbons out-fought and even appeared to out-speed Greb as he completed the route by actually driving the perpetual aggressor back and away. By the end, Greb’s left eye was closed and he carried evidence of Tommy’s terrible body attack from hip to chest.

Greb avenged himself upon Gibbons on two occasions. He would remain the only man to defeat Gibbons at the poundage and the latest in a long line to name Gibbons one of the best he had ever faced.

Grotesquely underrated in the modern era, Gibbons has neither the top-to-toe resume or a the prolonged championship run to allow him to pierce the top ten, but he is as close to doing so and as deserving of inclusion and as special as anyone who lies outside it.

#11 HAROLD JOHNSON (76-11)

Perhaps the most underrated heavyweight in history, Harold Johnson boxed with a care that suited his near-perfect technique; small moves, calculated strikes fluid combination punching born of correct balance, something that was not easy for Johnson to maintain with a relatively short reach. At light-heavyweight, however, I think a certain over-confidence crept into his work. It is a fact that the huge-punching “Oakland” Billy Smith is not the mindless brawler some try to paint him in the light of his embarrassment on film by the immortal Charley Burley, and it is true that the feint Smith buys his devastating one-punch knockout of Johnson with was a thing of real beauty, but there is still something surprising about his being knocked out by Smith despite his defensive prowess, clear on film at heavyweight. His knockdown at the hands of another huge puncher, Bob Satterfield may have cost him in that split-decision loss.

Nevertheless, at his best, Johnson was the definitive technician at both light-heavyweight and heavyweight. If Lloyd Marshall is the clown-prince of jazz at 175lbs, Harold Johnson is a master pianist, whose genius is born of his perennial correctness. It is the type of style that can lead to the utter domination of world class opposition. In 1963, a light-heavyweight world-title challenger named Doug Jones stepped up to heavyweight to take on a prospect named Muhammad Ali and pushed him as hard as he would ever be pushed until Joe Frazier grabbed hold of him. Around ten months before that, Jones met Harold Johnson with the 175lb title on the line and Harold won as many as thirteen of the fifteen rounds contested between the two in defence of the title he was born to wear. He had been a professional boxer for sixteen consummate years.

Clearly slowing down, Johnson drew his opponent’s quicker jab into space he had once inhabited rather than the space he would inhabit with simple, stark footwork that wasted not a single step and left Jones hanging. Whenever he got hit, he knew exactly where to place his counterpunches to discourage aggression; he threw with volume but never without control; he walked Jones onto his own left over and over again; when Jones shows bravery in coming squarer to try to make his right a factor, he just made himself more available for Johnson’s jab, which he first doubled, then trebled.

It’s perfection and like much that is perfect, it is simple, but if the reader could teach it he would have seven world-class prospects on his hands. There are two different senses in which a man can be a natural fighter, and Johnson epitomises the version which stresses not aggression but timing. He was once asked why, when he so often had fights sewn up early, he didn’t press for the stoppage and he answered that he would feel a fool if he were to be dropped by a dominated opponent in the final rounds. One wonders how much money his perfectionism cost him.

He was robbed of the title he strived so long and so hard to lift against Willie Pastrano in 1963. As blatant a robbery as can be seen in a filmed title fight, this injustice put the lights out in Johnson and he rambled home to retirement in 1968 and then again after an aborted comeback in 1971. Looking over his shoulder, he probably considered his single ten round victory over nemesis Archie Moore to be the jewel in his crown rather than five victories he achieved in title fights, but it should be stressed that Moore defeated him on four other occasions. I said it in writing about Johnson on the occasion of his death earlier this year and I’ll say it again here: the terrible luck Johnson suffered in sharing an era with his stylistic nightmare who also happened to be one of the greatest fighters of all time is stark. Had Moore never been born, Johnson would be locked firmly within the top three in my opinion.

As it is, the perfectionist lies just outside the top ten.

Above, giants.

Featured Articles

At Long Last: Marvelous Marvin Hagler to Finally Get His Statue in the ‘City of Champions’

At Long Last: Marvelous Marvin Hagler to Finally Get His Statue in the ‘City of Champions’

Not much good news comes out of Brockton, Massachusetts these days but I’ve got some.

Former undisputed middleweight champion Marvelous Marvin Hagler will be posthumously honored in the city he helped keep on the boxing map with a life-sized bronze statue produced by Brodin Studios in Kimball, Minnesota. The statue of Hagler, “in an action stance” will be unveiled on June 13th at a small space near to where the old Petronelli Gym was once located.

According to Hagler’s widow Kay, the space is now called the Marvelous Marvin Hagler Park.

That date, June 13, 2024 will be on the 43-year anniversary of Hagler’s 1981 rematch with Vito Antuofermo at the Boston Garden. As the new champion, Hagler was making the second defense of the world title he won in 1980 from Alan Minter. Hagler’s first shot at the title came in 1979 against Antuofermo in Las Vegas and was ruled a draw. The rematch was a mismatch.

The unveiling, scheduled for Thursday June 13 at 11 am, will also fall on the 31-year anniversary of Hagler’s 1993 induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, NY. Will thousands show up to celebrate like they did when another Brockton boxer was remembered?

Back in 2012, when a 22-foot-tall Rocky Marciano statue was put up by the WBC, many asked why Hagler didn’t also have a statue in Brockton and would he ever get one? The answer is yes.

Somebody finally did something for Hagler. Before he died in 2023, longtime Marciano family friend Charlie Tartaglia told me the reason he put up a bronze plaque for Hagler at Massasoit College with his own money was because as he put it, “Nobody ever did nothin’ for Hagler.”

Brockton state representative Gerry Cassidy secured the $150,000 needed from the state to build and maintain the long overdue statue in tribute to Hagler who died in 2021 at the age of 66.

Hagler’s new sculpture will be on display approximately two miles away from Rocky’s. It won’t be as tall as Marciano’s towering memorial but that’s fine, Rocky was a heavyweight while Marvin was a middleweight.

“This testament to a true hometown sports and community icon will be a permanent monument to one of the greatest champions from our ‘City of Champions,’” said Brockton Mayor Robert F. Sullivan in a public statement announcing the marvelous news.

The legendary physique of Hagler in his prime is befitting of a likeness commemorating it. Somebody on Facebook wrote, “I guarantee his jaw and muscles were stronger than his statue is going to be.” Another Facebooker wrote, “A fitting tribute to a boxing great gone too soon.”

Hagler reigned as middleweight champion of the world from 1980 to 1987 and during this time he carved out a reputation as one of the greatest middleweight champions in the history of boxing. Hagler was a member of the “Four Kings” which also included Sugar Ray Leonard, Thomas “The Hitman” Hearns and Roberto Duran. Hagler beat Duran and Hearns but lost to Leonard.

One of the reasons it took so long for Hagler to be honored in this way is that despite his greatness in the boxing ring, Hagler had another reputation in Brockton and that was as somebody with the capacity for violence against women, most notably his ex-wife Bertha.

Domestic incidents between the pair were common and in her complaint against Hagler, Bertha alleged that she lived in fear of Marvin; that he put his hands on her and threw a large rock at her car. Regardless of all this, Brocktonians are happy and excited to see Hagler and his surviving family finally get what’s coming to him even if it will come three years after Hagler passed away.

Still, not everyone in the City of Champions is so pleased with the planned placement of the new statue. As mentioned, the Hagler memorial will be located a couple miles away from Marciano’s.

“Hagler’s statue belongs at Brockton High School,” says Mark Casieri, owner and caretaker of Rocky Marciano’s childhood home located at 168 Dover Street. Casieri knows a thing or two about Brockton boxing. “It belongs there alongside Rocky’s statue so that the youth coming up through the school system are able to know the sports heroes that came out of Brockton.”

Brockton High School has been in the news recently but for all the wrong reasons. Violence and debauchery at the high school has gotten so bad that politicians considered bringing in military units of the National Guard to quell the unprecedented unrest. It’s ironic but Brockton has become like Newark, NJ, the city that Hagler’s mother moved him away from to protect him.

As a young middleweight just starting out as a professional fighter, Hagler fought nine of his early bouts at the Brockton High School gym including his pro debut against Terry Ryan in 1973.

For the record, I reached out to Brodin Studios for some information about the statue (its official height and weight? What fight is the action poise from?) but they are playing it very close to the chest, saying only what an honor it was to build it for Hagler and the entire Brockton community.

The Marvelous One is finally getting his statue in the City of Champions. Better late than never.

Photo insert: Marvin Marvin and Vito Antuofermo (undated; circa 2010)

*** Boxing Writer Jeffrey Freeman grew up in the City of Champions, Brockton, Massachusetts from 1973 to 1987, during the Marvelous career of Marvin Hagler. JFree then lived in Lowell, Mass during the best years of Irish Micky Ward’s illustrious career. A former member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and a Bernie Award Winner in the Category of Feature Story Under 1500 Words, Freeman Covers Boxing for the Sweet Science in New England.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Fury vs. Usyk: Who Wins and Why? – The Official TSS Prediction Page

The heavyweight division, it has been said, is the engine that drives the sport of boxing. By this measure, Saturday’s match in Saudi Arabia between Tyson Fury and Oleksandr Usyk is the most important fight in decades.

Whenever a very big fight comes down the pike – assuming the odds are not too lopsided – we call upon our fine community of wordsmiths to get their thoughts. The participants in the poll are listed alphabetically.

—

Simply put size matters. Usyk has never fought anyone that weighed more than 225 pounds and given Fury’s recent history it seems safe to assume he should tip the scales north of 260. Eleven years ago, Fury fought another former cruiserweight champion in Steve Cunningham. Cunningham’s speed gave Fury problems early and Fury was even knocked down. But Fury used his size and weight to lean on Cunningham draining him of all his energy. Eventually a badly fatigued Cunningham was knocked out by Fury. I see something happening when Fury faces Usyk. Usyk has success early and maybe even scores a knockdown or two. But Fury leans on Usyk and uses that weight advantage to slowly wear down the smaller man. FURY TKO 10. – MATT ANDRZEJEWSKI

After a lackluster and controversial split decision win over Francis Ngannou, Fury looks fit as a fiddle and should handle the six-inch shorter Usyk by keeping his distance and landing more than enough big blows. In a fight filled with drama and excitement, it’s FURY by unanimous decision. – RICK ASSAD

Fury’s jab and straight right vs. Usyk’s straight left and right hook (think Cotto vs. Pacquiao), whichever two-punch combination is more effective will decide who controls the range and pace. I believe Usyk’s straight left along with his southpaw stance and movement will give Fury trouble, but Usyk doesn’t attack like other smaller heavyweights to the body (i.e. Tyson/Frazier). Like Lomachenko, he uses his footwork to get inside, which will give him enough moments to make a focused and in-shape Fury take it to another level. Fury also isn’t a big body puncher, but he will use his size to lean on Usyk after he lands clean shots to wear Usyk down and gain control of the fight. FURY by decision. – LUIS CORTES III

Oleksandr Usyk is a good little man but he’s in way over his head against a well-trained Tyson Fury who looks to be treating this fight with the respect it deserves. Usyk will puzzle Fury for a few rounds but once Tyson makes his adjustments, he will bring his superior size and power to bear on the smaller fighter, wearing him out to the body and grinding him down late. I pick FURY by TKO in the championship rounds. Usyk will be on his feet when the fight is stopped but nobody will be crying foul about it. – JEFFREY FREEMAN

FURY by stoppage late. He’ll be in condition this time (unlike the Ngannou debacle). And an in-shape Fury boxes well enough and is too big and strong for Usyk to deal with. – THOMAS HAUSER

There’s always a chance that a fight will be stopped on cuts. Of the two, the Gypsy King would seem to be more prone to this unfortunate happenstance. He overcame a terrible gash over his right eye to upend Swedish southpaw Otto Wallin and it was a cut over his right eye during a sparring session – a cut that reportedly required extensive stitching — that pushed back this fight from its originally scheduled date of Feb. 17. Since this fight has a rematch clause, the ring physician may feel less pressure to allow the fight to continue against his better judgment if it boils down to this. Regardless, USYK has lost fewer rounds as a pro and it’s easy to envision the Ukrainian banking enough rounds to stave off a late rally by Fury to cop the decision. – ARNE LANG

A lot of ink has been shed on the cut Tyson Fury suffered in sparring causing a postponement of this fight to this coming Saturday; it’s Tyson Fury’s elbows that interest me though. Fury fought in terrible pain in his third contest against Deontay Wilder in 2021, taking cortisone injections in both elbows prior to this fight. Wilder actually outjabbed Fury early and Fury threw three or fewer jabs in seven of the eleven rounds. Since, he has been inactive (only three fights since his late 2021 defeat of Wilder), unimpressive (especially against novice Francis Ngannou last year) and irrelevant (the world needed Chisora III like it needs more inflation). In short, this fight, which once seemed so clear cut to me, will now be decided by intangibles. Fury looks sleek, I’m interested to see his weight. Over 265lbs and he’s struggling to get the jab working and will be here to maul a fleet-footed Usyk. Under and he thinks his elbows are right and he will look to control the smaller man with his range. Based on the videos team Fury have been releasing, I’ll go for Fury to dominate until his stamina starts to slide at which point, Usyk will take over – I think that will be late enough for Fury to get home with a decision win. But nothing would surprise me now. – MATT McGRAIN

Since his high profile wins over Deontay Wilder, madhatter Tyson Fury has carried himself like a dilettante (admittedly, not the first time he has been guilty of that charge in his erratic career) and the effects showed last year against Francis Ngannou, a boxing newbie who nearly (and risibly) secured a place in prizefighting lore next to Buster Douglas. Fury will find his usual advantages—size, footwork, counter punching—negated by Oleksandr Usyk, who, despite being a converted cruiserweight, has proven he can not only outthink his opponents but outwork them as well. USYK via Split Decision – SEAN NAM

FURY uses size alone for a UD 12, with little drama barring a cut. Unless the distractions of Fury’s celebrity lifestyle have eroded his mauling focus (the wake-up call against Ngannou probably remedied that), I can’t see how Usyk can win this though he’s proved me wrong before. Fury’s mobility makes it very doubtful Usyk will be able to get in and out unscathed to score like he did against Joshua or Dubois, and even more unlikely he can outgun Fury toe to toe. Still, Usyk has perfected his southpaw style into a puzzle nobody has solved yet so Fury might have some early problems. — PHIL WOOLEVER

Editor’s Note: It’s a fair guess that Fury vs. Usyk will be the most heavily bet fight of all time, surpassing Mayweather-Pacquiao. As a rule, fights in the “pick-‘em” range attract the most action. At mid-week, although the action was tilting toward Fury, “11/10 and take your pick” was still readily available. In fact, at some houses, the action is so well-balanced that the operator reduced his vigorish (i.e., the house commission assuming balanced action), going from a 20-cent to a 10-cent line, confident that he could not lose.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

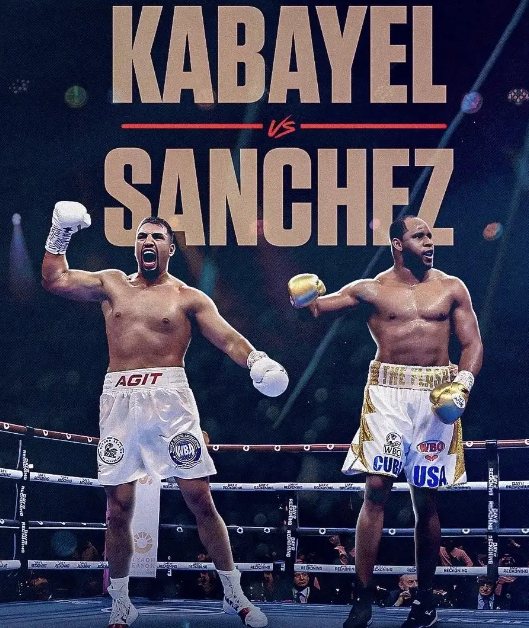

Will Kabayel vs Sanchez Prove to be the Best Heavyweight Fight This Weekend?

Will Kabayel vs Sanchez Prove to be the Best Heavyweight Fight This Weekend?

Tyson Fury and Oleksandr Usyk meet on Saturday at Kingdom Arena in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Barring a draw, the match will produce the first undisputed heavyweight champion in the four-belt era.

The bout is supported by an outstanding undercard that includes a heavyweight fight that may prove to be more entertaining than the headline attraction.

On paper, there’s little to separate Agit Kabayel and Frank Sanchez. Both are listed at 31 years old, arguably the optimal age for a heavyweight. Both are 24-0. Sanchez has 17 knockouts to his credit; one more than Kabayel. Both appeared in this ring on Dec. 23, so neither in theory has any rust.

Kabayel, born in Germany of Kurdish descent, upset the odds in a career-best performance, stopping Arslanbek Makhmudov in the fourth round. Heading in, the “Russian Lion,” who carried 262 pounds on his six-foot-six frame, was 18-0 with 17 knockouts, of which 12 came in the opening round.

This was no fluke knockout. Kabayal chopped him down, scoring three knockdowns with body punches until the fight was waived off.

On the same bill, Frank Sanchez scored a seventh-round stoppage of New Zealand’s Junior Fa. This fight took a long time to heat up, but when it did, the kiwi was outclassed.

Of the two, Sanchez is the smoother boxer. His signature win was a comprehensive 10-round decision over otherwise undefeated Efe Ajagba. He’s also taller than Kabayel who is generously listed at six-foot-three.

As an amateur, Sanchez was purportedly 214-6. And although that record was manufactured from thin air, there’s no doubt that the Cuban Flash, whatever his true amateur record (boxrec has it 43-12), was top-shelf in a pod replete with some of the world’s top amateurs.

By contrast, Agit Kabayel reportedly had only five amateur fights before turning pro.

Sanchez has been training at Eddy Reynoso’s compound in San Diego. That’s another “plus” for him on the handicapping checklist. However, Kabayel is the harder puncher and we suspect that Sanchez is actually older than his listed age, a common deception among Cuban athletes after they leave the island.

Kabayel will have more rooters, which may or may not affect the betting marketplace. His style is more fan-friendly and he’s had a harder road to get to this point in his career. After upsetting Derek Chisora in 2017, he fought only once in each of the next five years, a slowdown related to Covid, managerial issues, and fights falling out.

—

The WBC has sanctioned Kabayel vs Sanchez as an eliminator with the winner next in line to fight the winner of Usyk vs. Fury. But don’t hold your breath. The Fury-Usyk fight has a rematch clause and if the Gypsy King wins, Anthony Joshua will almost certainly leapfrog to the head of the queue.

History informs us that whoever wins the Usyk-Fury fight likely won’t stay undisputed for very long. One or more of the organizations will strip the title-holder for failing to fulfill his mandatory.

That’s what happened to Lennox Lewis after he won his rematch with Evander Holyfield. Nine months later, after Lewis demolished Michael Grant and Frans Botha, Holyfield won the vacant WBA world heavyweight title with a narrow decision over John Ruiz in the first of their three meetings.

In boxing, the more things change, the more they remain the same.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoIn a Massive Upset, Dakota Linger TKOs Kurt Scoby on a Friday Night in Atlanta

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoHaney-Garcia Redux with the Focus on Harvey Dock

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoIn a Shocker, Ryan Garcia Confounds the Experts and Upsets Devin Haney

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 281: The Devin Haney and Ryan Garcia Show

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRamirez Outpoints Barthelemy and Vergil Ortiz Scores Another Fast KO in Fresno

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoA Closer Look at Weslaco ‘Heartbreaker’ Brandon Figueroa and an Early Peek at Inoue vs Nery

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoHaney and Garcia: Bipolar Opposites

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRamon Cardenas Channels Micky Ward and KOs Eduardo Ramirez on ProBox