Articles

Fathers and Sons

Youngstown, Ohio played an important role in my childhood memories: it stood as the rough halfway point for two-day drives between Deerfield, Illinois, where I grew up, and New York, where both my parents had relatives. Youngstown meant the end of Day One’s drive, a swim in a hotel pool, and all the other minor excitements kids find in travel.

Youngstown, Ohio played an important role in my childhood memories: it stood as the rough halfway point for two-day drives between Deerfield, Illinois, where I grew up, and New York, where both my parents had relatives. Youngstown meant the end of Day One’s drive, a swim in a hotel pool, and all the other minor excitements kids find in travel.

In June 1982, it also meant a phone call to Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini.

Actually, it was my brother who made the call. We were surprised to find a Mancini listed in the Youngstown phonebook; if memory serves, the listing was for Ray’s father, Lenny “Boom Boom” Mancini. The old man answered. Is Ray there? My brother asked. No, said the old man, who’s calling? In the background, my brother thought he heard a voice—Ray’s—asking, Who is it?

He identified himself and told Lenny that he was calling to congratulate Ray on winning the WBA lightweight championship from Arturo Frias a month earlier. Lenny thanked him, said he’d pass the message on to Ray, and hung up.

Pretty forgettable, unless you’re a teenager. We talked about it for days.

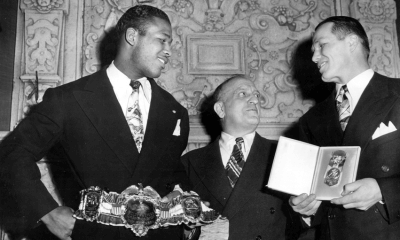

Back in 1982, everyone was talking about Ray Mancini. The 21-year-old lightweight was becoming one of the biggest names in boxing. He had it all: a crowd-pleasing style, in which he often threw in excess of 100 punches per round; a personal story, involving his love for his father and his desire to win the championship for him, that would put Rocky to shame; and boxing’s oldest marketing lubricant—ethnicity. Mancini was a throwback to great Italian fighters of decades past, when the “white ethnics”—especially the Irish and Italians—dominated the lower weight divisions.

Lenny Mancini was ready to join that lineage in the early 1940s, but World War II short-circuited his career. He was injured in combat near Metz in France and never got his title shot, settling down to family life in blue-collar Youngstown. By the time Ray Mancini entered the boxing spotlight, Youngstown had fallen on hard times and badly needed a rallying point. Mancini was marketing gold: his fights were televised on CBS, and Madison Avenue wanted to sign him up.

“It was like Leave it to Beaver,” says Gina Andriolo, who handled Mancini’s contracts. “Except Beaver was knocking guys out.” Mancini’s lone defeat, to Alexis Arguello in 1981, had only ennobled him: just 20 years old, he had fought the great Nicaraguan nearly to a standstill before the fight was stopped in the 14th round. The two men’s post-fight embrace seemed to exemplify what was good in boxing.

Just as Mancini’s popular appeal was cresting in November 1982, Sugar Ray Leonard announced his retirement (he’d later reconsider), and boxing had an opening for the job of Top Star. In a sport dominated by black and Hispanic fighters, Mancini—“symbolically potent, demographically perfect,” as Mark Kriegel writes—seemed to be the guy. Then fate intervened.

Kriegel’s new biography, The Good Son, tells all of this with an intimacy of detail and a minimum of editorializing, and the result is a book that brings the Boom Boom saga alive in all of its bloody, intergenerational passion. It’s the story of Lenny, a brawler so fierce that Rocky Graziano avoided him, telling him decades later: “Boom Boom, you were the only guy got pissed off when someone swung and missed you.” It’s the story of Lenny’s two sons: Leonardo, the bad-boy, howling rebel who ends up dying young from an errant pistol shot; and Raymond, the good son of Kriegel’s title, an eight-year-old who so adores his father that he tracks him down in Youngstown bars to bring him home, and who pores over Lenny’s old boxing scrapbooks. It’s the story of mobbed-up, deindustrialized Youngstown, rife with crime, unemployment, and broken lives. And it’s the story of Duk Koo Kim, Young Mee, and their son Jiwan, not yet born when his father dies in November 1982 after losing a championship match against Mancini.

Kriegel is steeped in boxing and has talked to just about anyone who could tell him anything about the Mancinis, about Youngstown, and about boxing in its last golden era. For Kriegel, Mancini’s story is also about our need for stories, especially those we make out of our own lives. Winning the lightweight title for his father was a fable Ray Mancini wrote in his head as a little boy and then set out to make real. But Mancini isn’t the only person in The Good Son determined to star in his own redemption tale.

Duk Koo Kim was a poor, fatherless Korean boy born to a mother he called “a woman of great misfortune.” His earliest memories were of hunger and wandering. He slept under bridges, peddled pens on Korean buses, and seemed marked out for a life of poverty and invisibility. Yet he developed a vision of himself as a man of consequence. Somewhere deep down, he knew that he was worth a damn, that he deserved respect and dignity and love. Imagine that. What really set Duk Koo apart was that he was willing to go to extraordinary lengths to prove it. So powerful is Kriegel’s portrait of Kim that at times he rivals the book’s main character.

Mancini, who came into every fight in physical condition few, if any, opponents could match—he carried 70-pound sandbags up hills and was an early adopter of weightlifting—had watched films of his challenger’s bouts and knew what many boxing scribes did not: that Kim was “going to be a headache.” On the lampshade in his Las Vegas hotel room, Kim scrawled a message in Korean that translated to “live or die” or perhaps “kill or be killed.” Through his dressing-room walls before entering the ring, Mancini heard Kim pounding the lockers and screaming—“war cries,” Mancini remembered.

The Mancini-Kim fight would become, in Kriegel’s chilling phrase, “a stubborn accrual of brutalities.” At the bell for the first round, Kim ran across the ring and hit Mancini flush in the mouth, and the battle was on. The crowd ringside and the CBS broadcast team of Tim Ryan, Gil Clancy, and the just-retired Ray Leonard marveled at the bombs both fighters were throwing. Kim was outmatched but unyielding; Mancini scored heavily in the first half of each round, but Kim would roar back before the bell. Gradually, Mancini’s superior physical strength began to tell. In the 13th round, Mancini looked ready to put Kim away, but in the last minute the challenger rallied yet again. The stage seemed set for a dramatic finish, but when Mancini charged off his stool for the 14th, Kim finally wilted, going down from one last Mancini combination. Using the ropes, Kim somehow pulled himself up—the late Ralph Wiley, writing then for Sports Illustrated, called it “one of the greatest physical feats I had ever witnessed”—but he could barely stand, and the referee stopped the fight. Not learning of Kim’s condition until later, Mancini celebrated his hardest victory.

Kim was taken out of the ring in a stretcher, and it was soon clear that his condition was hopeless. “There is severe brain swelling,” the physician who operated on him told reporters. “The pressure will go up and up, and that will be it. He'll die.” Kim’s mother, Sun-Nyo Yang, flew in from South Korea in time to sit by his bedside, where a consultation among other family members resulted in agreement that, in a doctor’s words, Kim “belong[ed] with the dead.” His life support was disconnected. Three months later, Sun-Nyo killed herself by swallowing pesticide. Kriegel tells us that she did so before she could receive a letter—even then in transit—from Mancini’s mother, in which she offered Sun-Nyo a home with the Mancini family. In July 1983, the bout’s referee, Richard Green, was found dead of an official suicide (disputed by some).

With a body count like that, the Mancini-Kim fight will never be forgotten, but its casualties didn’t end with the dead. A sensitive and religious man, Mancini was devastated, and he went through the motions in subsequent fights. The ad men skulked away from his door; Madison Avenue’s business model rests on denying death, not confronting it. The Kim fight and its aftermath, Kriegel writes, cost Mancini “his standing as an All-American boy, his legitimacy as a suitor for both Miss Ohio and Coca-Cola.” And for many, the fight’s long-term victim was boxing itself, which began to lose its mainstream appeal, especially on TV. “The ratings dropped like a rock after that,” then-CBS boxing head Mort Sharnik tells Kriegel. “After a few years, boxing was no longer on the networks.” The fight also prompted the eventual shortening of championship fights from 15 rounds to 12, the standard today.

When Mancini rebounded in January 1984, stopping the formidable Bobby Chacon in three incendiary rounds, some saw a flash of the old Boom Boom, but it was not to be. He’d never win again. In June of that year, Mancini lost his title in an upset to Livingstone Bramble, a counterpunching Rastafarian with a penchant for boa constrictors and curses. Bramble fostered bad blood prefight by calling Mancini a “murderer,” correctly sensing that it would drive the champion out of his head. But it was a clash of heads in the first round that threatened Mancini’s title, causing a wicked cut over his right eyelid. His brilliant cutman, Paul Percifield, kept it contained, however, and Mancini entered the 14th round—that round again—with the lead on two scorecards. That’s when Bramble stunned him with a combination that took his legs away and left him defenseless along the ropes. The referee moved in.

The loss to Bramble meant the shelving of several big-money fights for Mancini, including a match against Hector Camacho and an irresistible Battle of Ohio against Cincinnati’s Aaron Pryor. Instead, he took on Bramble again, losing a decision by a one-point margin on all three scorecards despite fighting the better half of the bout with cuts that looked sure to land him in an emergency room. (As Warren Zevon’s homage to Boom Boom put it: “If you can’t take the punches, it don’t mean a thing.”) The bitter adversaries embraced at last—Bramble is full of praise for Mancini in The Good Son—and Mancini waved to the crowd like a winner. He’d come back twice more, as champions do, and lose, as champions must.

Kriegel’s final chapters have a familiar ring: the ex-fighter’s need to hear the roar of the crowd once again; the emptiness and bafflement of “normal” life, for which he has no training; and the toll boxing exacts on body, mind, and spirit. “One way or another, those intimate with violence were corrupted or imperiled by it,” Kriegel writes, chronicling the somber fates of many of Mancini’s peers. “They go from being famous and adored to being nobodies,” says Mancini’s ex-wife, Carmen Vazquez. “Boxers, I think, have really sad lives.”

Mancini’s story has had its share of that sadness, but he remains among the rarest of ex-fighters, with money in the bank and apparently good health. He manages a film production company and moves in circles that include the playwright and screenwriter David Mamet. Best of all, through Kriegel’s efforts, he has been blessed with the chance to meet with Duk Koo Kim’s survivors—his fiancée Young Mee and Jiwan, the boy she was carrying when her prospective husband died in the ring. Jiwan gives Mancini the absolution not even God could afford him: “I think it was not your fault…Maybe now your family will be more happy.”

Maybe. But happiness is never really the goal.

Articles

2015 Fight of the Year – Francisco Vargas vs Takashi Miura

The WBC World Super Featherweight title bout between Francisco Vargas and Takashi Miura came on one of the biggest boxing stages of 2015, as the bout served as the HBO pay-per-view’s co-main event on November 21st, in support of Miguel Cotto vs Saul Alvarez.

Miura entered the fight with a (29-2-2) record and he was making the fifth defense of his world title, while Vargas entered the fight with an undefeated mark of (22-0-1) in what was his first world title fight. Both men had a reputation for all-out fighting, with Miura especially earning high praise for his title defense in Mexico where he defeated Sergio Thompson in a fiercely contested battle.

The fight started out hotly contested, and the intensity never let up. Vargas seemed to win the first two rounds, but by the fourth round, Miura seemed to pull ahead, scoring a knock-down and fighting with a lot of confidence. After brawling the first four rounds, Miura appeared to settle into a more technical approach. Rounds 5 and 6 saw the pendulum swing back towards Vargas, as he withstood Miura’s rush to open the fifth round and the sixth round saw both men exchanging hard punches.

The big swinging continued, and though Vargas likely edged Miura in rounds 5 and 6, Vargas’ face was cut in at least two spots and Miura started to assert himself again in rounds 7 and 8. Miura was beginning to grow in confidence while it appeared that Vargas was beginning to slow down, and Miura appeared to hurt Vargas at the end of the 8th round.

Vargas turned the tide again at the start of the ninth round, scoring a knock down with an uppercut and a straight right hand that took Miura’s legs and sent him to the canvas. Purely on instinct, Miura got back up and continued to fight, but Vargas was landing frequently and with force. Referee Tony Weeks stepped in to stop the fight at the halfway point of round 9 as Miura was sustaining a barrage of punches.

Miura still had a minute and a half to survive if he was going to get out of the round, and it was clear that he was not going to stop fighting.

A back and forth battle of wills between two world championship level fighters, Takashi Miura versus “El Bandido” Vargas wins the 2015 Fight of the Year.

WATCH RELATED VIDEOS ON BOXINGCHANNEL.TV

Articles

Jan 9 in Germany – Feigenbutz and De Carolis To Settle Score

This coming Saturday, January 9th, the stage is set at the Baden Arena in Offenburg, Germany for a re-match between Vincent Feigenbutz and Giovanni De Carolis. The highly anticipated re-match is set to air on SAT.1 in Germany, and Feigenbutz will once again be defending his GBU and interim WBA World titles at Super Middleweight.

The first meeting between the two was less than three months ago, on October 17th and that meeting saw Feigenbutz controversially edge De Carolis on the judge’s cards by scores of (115-113, 114-113 and 115-113). De Carolis scored a flash knock down in the opening round, and he appeared to outbox Feigenbutz in the early going, but the 20 year old German champion came on in the later rounds.

The first bout is described as one of the most crowd-pleasing bouts of the year in Germany, and De Carolis and many observers felt that the Italian had done enough to win.

De Carolis told German language website RAN.DE that he was more prepared for the re-match, and that due to the arrogance Feigenbutz displayed in the aftermath of the first fight, he was confident that he had won over some of the audience. Though De Carolis fell short of predicting victory, he promised a re-vamped strategy tailored to what he has learned about Feigenbutz, whom he termed immature and inexperienced.

The stage is set for Feigenbutz vs De Carolis 2, this Saturday January 9th in Offenburg, Germany. If you can get to the live event do it, if not you have SAT.1 in Germany airing the fights, and The Boxing Channel right back here for full results.

Articles

2015 Knock Out of the Year – Saul Alvarez KO’s James Kirkland

On May 9th of 2015, Saul “Canelo” Alvarez delivered a resonant knock-out of James Kirkland on HBO that wins the 2015 KO of the Year.

The knock-out itself came in the third round, after slightly more than two minutes of action. The end came when Alvarez delivered a single, big right hand that caught Kirkland on the jaw and left him flat on his back after spinning to the canvas.Alvarez was clearly the big star heading into the fight. The fight was telecast by HBO for free just one week after the controversial and disappointing Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao fight, and Alvarez was under pressure to deliver the type of finish that people were going to talk about. Kirkland was happy to oblige Alvarez, taking it right to Alvarez from the start. Kirkland’s aggression saw him appear to land blows that troubled the young Mexican in the early going. Alvarez played good defense, and he floored Kirkland in the first round, displaying his power and his technique in knocking down an aggressive opponent.

However, Kirkland kept coming at Alvarez and the fight entered the third round with both men working hard and the feeling that the fight would not go the distance. Kirkland continued to move forward, keeping “Canelo” against the ropes and scoring points with a barrage of punches while looking for an opening.

At around the two minute mark, Alvarez landed an uppercut that sent Kirkland to the canvas again. Kirkland got up, but it was clear that he did not have his legs under him. Kirkland was going to try to survive the round, but Alvarez had an opportunity to close out the fight. The question was would he take it?

Alvarez closed in on Kirkland, putting his opponent’s back to the ropes. Kirkland was hurt, but he was still dangerous, pawing with punches and loading up for one big shot.

But it was the big shot “Canelo” threw that ended the night. Kirkland never saw it coming, as he was loading up with a huge right hand of his own. The right Alvarez threw cracked Kirkland in the jaw, and his eyes went blank. His big right hand whizzed harmlessly over the head of a ducking Alvarez, providing the momentum for the spin that left Kirkland prone on the canvas.

Saul “Canelo” Alvarez went on to defeat Miguel Cotto in his second fight of 2015 and he is clearly one of boxing’s biggest stars heading into 2016. On May 9th Alvarez added another reel to his highlight film when he knocked out James Kirkland with the 2015 “Knock Out of the Year”.

Photo by naoki fukuda

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoMekhrubon Sanginov, whose Heroism Nearly Proved Fatal, Returns on Saturday

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 322: Super Welterweight Week in SoCal

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

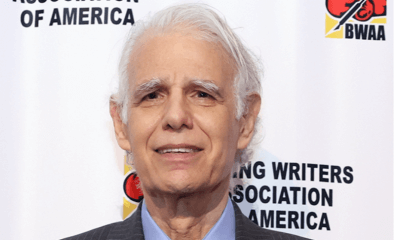

Featured Articles4 weeks agoTSS Salutes Thomas Hauser and his Bernie Award Cohorts

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoGabriela Fundora KOs Marilyn Badillo and Perez Upsets Conwell in Oceanside

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks ago‘Krusher’ Kovalev Exits on a Winning Note: TKOs Artur Mann in his ‘Farewell Fight’

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFloyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The First Boxing Writers Assoc. of America Dinner Was Quite the Shindig

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More