Featured Articles

Shadow Boxing at the Golden Gate, Part 2

“Most men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them.”

—Henry David Thoreau

“Redcap” Eddie’s blitz began under a shadow of concern, particularly Eddie Muller’s. The writer openly wondered about his “long layoff” and thus underlined the difference between fighters then and fighters now: the lag time since Booker’s last bout was only seven months.

“Booker isn’t picking a soft one,” wrote Muller. Harry “Kid” Matthews had not been stopped in forty-three bouts and had a left hook that was turning all kinds of heads. It looked like a classic boxer versus puncher match-up with Booker as the boxer. Muller, who understood that a fighter with compromised vision had to make adjustments, saw things differently. He wrote that Booker will “do more punching than boxing” and will “make Matthews hustle at close quarters” and that is precisely what happened. Booker tore into his young opponent and smothered anything he tried to do while winging punches to the flank. When two short rights landed to his chin in the second round, Booker just “shook ‘em off” and soon landed a right uppercut that saw Matthews’ knees sag. The match was stopped in the fifth round.

After that beating, Matthews sought less violent settings and enlisted in the U.S. Army. He resumed his career in 1946 and won his next fifty-two fights.

Booker first met Holman Williams at Madison Square Garden in 1939 on the Joe Louis-John Henry Lewis undercard.The first of what would be three studies in skill and violence ended in a draw. Williams, a 2008 International Boxing Hall of Fame inductee and Eddie Futch’s pick as “the greatest pure boxer” he had ever worked with, was matched skill-for-skill and punch-for-punch.

The second time they met was four years later. Thanks to Muller, we know what happened. Williams was on wheels, a “hit-and-run artist” operating behind an educated jab while Booker practiced the dark arts of body-snatching. Booker was storming in while William’s jab and superior speed neutralized his attack. In the eighth and ninth, he was even making him miss wildly and outslugging him at close quarters. In the tenth, Booker shoveled in a right uppercut, hurt him and pinned him on the ropes. The fight was even. In the last round, both answered the bell with war-hats though Williams’ light artillery—the jab—reasserted itself to earn the judges’ nod.

Booker privately blamed the loss on sweating weight off shortly before the bout. Within two months he stepped into the ring at a comfortable 170 lbs against a heavyweight. Booker floored him twice before the referee spared his ribs by stopping the fight.

The Mongoose was next in line. The day after they fought to a draw in 1941, Archie Moore was raking leaves in his front yard when he suddenly felt like a “red-hot iron” had been thrust into his stomach. As he was lying there on the grass blaming Booker’s body shots, his aunt called an ambulance. “I was sure that I was dying,” he recalled. Doctors told him that he had suffered a perforated ulcer and emergency surgery was required to save his life. After eleven months he recovered, returned to the ring, and signed to face his nemesis again. With a license plate stuck inside the waistband of his no-foul protector, Archie barreled after Booker in the rematch, put him down—and barely got by with another draw.

After two contests, neither could claim superiority over the other. Booker later said that he knew how tough Moore was and informed his manager that he was in no hurry to meet him a third time. Moore wasn’t eager either, though back then reluctance wasn’t so synonymous with avoidance. Their third and final battle was scheduled for January 21st 1944.

Muller’s favorite fighter prepared himself by sparring with Pat Valentino, a San Francisco heavyweight. Muller was in the gym. Neither “held anything back,” he wrote, “and as a result, Booker was able to whip himself into tip top shape.”

The first four rounds of Booker-Moore III saw both men fighting on even terms as they sketched their strategic outlines with short punches inside. The crowd, art lovers none, was booing. Then Booker hit Moore with his easel. He landed a left hook in the fifth and down went Moore like a drop cover, barely beating the count when the round ended. The sixth and seventh rounds saw the Mongoose saved by the bell twice more. In the eighth, another left hook sent him down with plenty of time left in the round. Seconds later, Moore was sinking in slow motion when the referee thrust Booker’s hand in the air.

It was among the most decisive defeats of Moore’s long career; the first time he was stopped in over sixty bouts, and he was in his self-declared prime.

The victory prompted an Oakland promoter to try to sign Booker and Charley Burley for February 22nd or 23rd. It fell through. Booker may have welcomed a chance to avenge himself against Jack Chase, but the prognosis on his eye was getting steadily worse and there was unfinished business with Holman Williams.

The result of Booker-Williams III would either even up the score or see Williams win the series. Besides defeating Booker, Williams had also dominated Booker’s conqueror in Chase twice the previous month. The Chicagoan was installed as a 2-1 favorite, but Muller knew that Booker’s time was running out and smelled an upset. He knew the fury born of desperation.

As the fighters met in the middle of the ring at the Civic Auditorium, Williams immediately tried to re-establish that “snake like jab,” only this time, Booker was slipping it and ripping shots to the body. For the next three rounds Muller saw his man “charging in and banging away with lefts and rights” to the midsection; and in the third the crowd jumped to its feet when he smashed Williams with two rights to the jaw. Williams was forced to exchange and although he was outlanding the relentless body-snatcher and outsmarting him in close and at range, it was Booker’s guns that carried more force. The tenth could have been a candidate for “Round of the Year” as both “slugged it out for three full minutes without let-up.”

Muller’s penchant for suggesting strategy and then seeing his suggestions confirmed in the performance were on display. He insisted before the bout that Booker’s extra poundage will help if he “puts it to good use” and gets rough inside without getting careless. “Eddie must give his all,” Muller predicted, “he can’t afford to loaf at any time.” Eddie paid attention.

As his hand was raised at the final bell, the applause shook the rafters.

The war that was Booker-Williams III was talked about for days afterward around the Bay Area. Muller gave it a considerable amount of press and believed that the victory would place Booker in a position to demand a shot against Jake LaMotta if he came to San Francisco. The fight took in $11,972.15, which was good enough for a non-white main event to encourage the promoter to consider a fourth bout for early April.

April turned out to be a busy month for Murderers’ Row. LaMotta never did come west—so the Row went looking for him: On April 21st, hard-punching Lloyd Marshall, whom Booker had beaten so impressively, took a unanimous decision over the Bronx Bull in Cleveland. On the same day, Burley humiliated Moore almost as badly as Booker did in Hollywood. Chase lost to Burley on April 6th and three weeks later went the last seven rounds against Williams with a dislocated jaw and lost better.

Booker, twenty-seven and almost half-blind, was the odd man out. An ophthalmoscope saw that his gloves were hung on a hook.

Rated by The Ring in the welterweight, middleweight, and light heavyweight divisions from April 1939 through June 1944, he ascended to a career-high number two in the world after his last bout and finished with a record of 66-5-8. Fighters campaigning up and down the West Coast breathed easier when he retired. Burley, with five bouts at the auditorium under his belt, narrowly missed a collision with him and was lucky for it. He told a mutual sparring partner that Booker would have been his “hardest fight.”

He was right. Booker’s fateful decision to resume his career despite the risks unveiled a level of craft and character rarely seen. The golden blitz—those last frenzied fights over a seven-month stretch—were finishing touches to a monument that stood in the shadow of the Golden Gate Bridge.

It stands there still, under the dust of seven decades.

It stands despite the silence of seven decades.

Like travelers at the railroad station who barely noticed the redcap carrying their bags, who never saw the danger in those gnarled knuckles or the glint in that dying eye, the sport of boxing has failed to recognize Eddie Booker. Not long after his retirement, A.J. Liebling mentioned him as an opponent of Archie Moore who “left no footprints on the sands of time.” The Baltimore African American thought he was white.

Booker shrugged his shoulders and moved on, though not very far. He took time to train local amateurs who followed him through Golden Gloves tournaments and became a licensed corner man in the Bay Area. For twenty years he was the polite and unassuming clerk at Post Hardware on Sutter Street. The store was on the same street as his home and only a short walk from the Civic Auditorium.

Eddie Muller, our invaluable eyewitness for so many of his bouts, stayed close too. The San Francisco Examiner was located at the intersection of 3rd, Kearney, and Market, just a few blocks south of Sutter. Known as “Mr. Boxing,” Muller covered nothing but the Sweet Science in his column “Shadow Boxing.” It ran for forty-four years. He bore black and white witness to the quiet man’s wars, aged with him, and remembered him at the end.

Thirty years after his last great victory over a third Hall of Famer, Booker’s heart stopped and Muller—still there for him and for us—wrote his obituary.

It was fitting.

__________________

It is the strong opinion of this writer that both Eddie Booker and Eddie Muller are overdue for induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Details about Booker found among the papers of Hank Kaplan. Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Archive is located at the Brooklyn College Library. Special thanks to Harry Otty, Jahongir Usmanov of the Brooklyn College Archives, and Eddie Muller II, the illustrious son of “Mr. Boxing” and the author of two widely-acclaimed noir novels in The Distance and Shadow Boxer —both of which conjure the spirit and the times of Muller and Booker.

Springs Toledo can be contacted at scalinatella@hotmail.com.

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles2 days ago

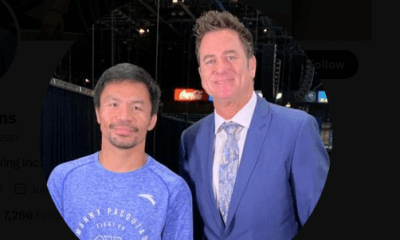

Featured Articles2 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons