Featured Articles

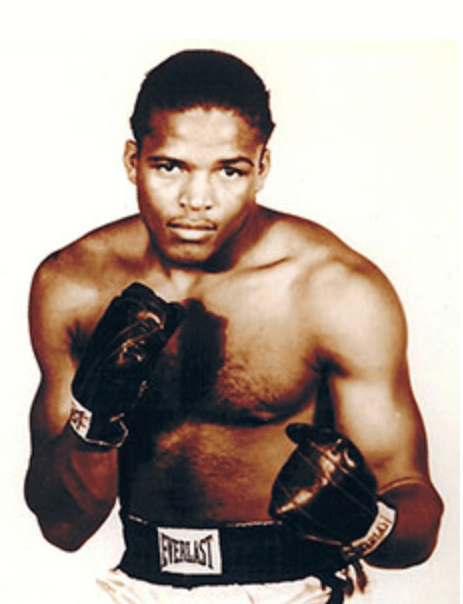

Philadelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

On July 7, 1952, a crowd of 39,025 turned out at Philadelphia’s Municipal Stadium to witness Kid Gavilan defend his world welterweight title against Gil Turner. According to some reports, the attendance was only a few hundred shy of the welterweight record set by Jimmy McLarnin and Barney Ross in their first meeting in 1934.

Gavilan, the Cuban Hawk, master of the polo bunch, was an 11/5 favorite, but 21-year-old Gil Turner had the crowd in his corner. He was Philadelphia born and bred, a boxer with a slew of amateur trophies who had stayed loyal to his amateur coach Willie Reddish, one of several good black heavyweights who were tread-milled during the title reign of Joe Louis.

Gil Turner turned pro on May 1, 1950, three weeks after steamrolling five opponents to win the National AAU welterweight tournament at Boston Garden. Before the year was out, he was 13-0, having chopped down 13 opponents in quick order with only one lasting beyond the third round.

In 1951, Turner had one of the best years ever by a boxer who was still new to the game. He was 14-0 that year, defeating such notables as Beau Jack (twice), Charley Fusari, Ike Williams, and Bernard Docusen. The Fusari and Williams fights were at Shibe Park, the home of the city’s two major league baseball teams, the Phillies and Athletics.

Beau Jack was the first of the quartet to suffer defeat at the hands of the phenom. Turner, appearing in his first 10-rounder and first main event, outclassed the former Augusta, Georgia bootblack, winning every round on one of the scorecards and eight rounds on the others. That was a nice feather in Turner’s cap. Cumulatively speaking, Beau Jack was the top draw in boxing during the World War II era, routinely drawing near-capacity crowds at Madison Square Garden.

There was really no need for a rematch. To sell it, promoter Herman Taylor’s minions amped up the hype. A writer for a small Pennsylvania paper, writing with one hand in Taylor’s pocket, wrote that the first meeting was such a corker that the promoter was bombarded with a thousand letters demanding a rematch.

But in hindsight, the rematch was hardly superfluous for Team Turner as Gil was able to stop Beau Jack, something an outstanding Philadelphia fighter, Bob Montgomery, was unable to accomplish in 55 rounds with Jack spread across a four-fight series.

Turner ended the match in the eighth round. After rocking Beau Jack with an uppercut, Turner let loose a barrage of punches that left Jack in such a bad way that the referee was forced to step in and stop it.

Turner’s stock soared higher when he KOed Charley Fusari in the 11th frame of a 12-round contest. Four months prior to meeting Turner, New Jersey’s Fusari, the “Irvington Milkman” (he bought his parents a milk route with his ring earnings), had gone 15 rounds with NBA welterweight titlist Johnny Bratton, losing a split decision, and he had been stopped only once previously, that coming in the final minute of a 10-round bout with Rocky Graziano, a fight that Fusari was winning.

Turner “beat Fusari to a pulpy wreck before putting him down for the count,” said the correspondent for the Philadelphia Evening News.

Ike Williams was recognized as a Philadelphia fighter although, akin to Fusari, he resided in neighboring New Jersey. Prior to meeting Gil Turner, Ike was 35-4-1 in Philadelphia rings including sixth-round stoppages of Beau Jack and Bob Montgomery when Ike was the best 135-pound boxer in the world.

Turner stopped the former world lightweight champion with 28 seconds remaining in the 10th and final round. He dominated the fight and had Williams out on his feet, held up by the ropes, when the fray was terminated.

His match with Bernard Docusen was even more one-sided. “So much leather was tossed [by Gil Turner] that you couldn’t keep track of the punches,” said the Associated Press correspondent who wrote that the Philadelphia phenom reminded him of Henry Armstrong.

Docusen retired on his stool after six frames. Three years earlier, the New Orleans cutie had gone 15 rounds with Sugar Ray Robinson in a failed bid for Robinson’s welterweight title.

Truth be told, these five wins over the four standouts – Jack, Fusari, Williams, and Docusen – warrant an asterisk. All four were in the twilight of their career. Beau Jack and Ike Williams — both part of the inaugural class of the International Boxing Hall of Fame — were especially shopworn. However, one could fairly say that Turner hastened their departures. Fusari fought only twice more after meeting Turner and Docusen had only five more fights before taking his leave but, chronologically speaking, both were mere pups compared with many modern-day gladiators when they shut things down. Fusari was 27; Docusen 25.

Turner finished off his glorious year headlining a show at Madison Square Garden. He won a wide decision over Connecticut journeyman Vic Cardell and then, after winning four more fights, came his big opportunity, a date with world welterweight champion Kid Gavilan.

Gil Turner and Kid Gavilan flank promoter Herman Taylor

Gavilan vs. Turner was competitive through the first 10 stanzas. Two of the judges had it even. However, the tide was turning in Gavilan’s favor and much to the chagrin of the locals, the defending champion ended matters in the 11th. Turner was sagging against the ropes with his mouthpiece dangling from his lips when the referee stopped it.

That was Turner’s first defeat after opening his career 31-0. Many more setbacks would follow, but there were some highs mixed among the lows and the erstwhile phenom, routinely matched tough, remained a formidable foe for any of the top dogs in his weight class.

Turner lost his first post-Gavilan fight, losing a split decision to 111-fight veteran Bobby Dykes, but rebounded to win five of his next six to climb back to the top of The Ring magazine ratings. That brought about a match with #2 contender Johnny Saxton at the Philadelphia baseball park (renamed Connie Mack Stadium), a compelling attraction that proved to be even better than advertised.

Saxton, raised in a Brooklyn orphanage, was a phenom himself, undefeated in 40 fights with one draw.

The two 22-year-old welterweights battled hammer-and-tongs for 10 lusty rounds. Turner was trailing through seven, but came on strong to win a razor-thin, but well-received, decision. (They fought again three years later in Chicago. Saxton won the 10-rounder on cuts when the ring doctor wouldn’t let Turner come out for the last round. By then, Johnny Saxton had won and lost the welterweight title.)

Turner’s ledger was spotty following his first encounter with Saxton. He was 20-16-2 from that point forward. He hit a rough patch in 1955 when he was out-pointed by Gene Fullmer, Carmen Basilio, and Isaac Logart in consecutive bouts, but things weren’t mellow on the home front and that may have been a contributing factor. A story in the May 18, 1955, issue of Jet magazine, said that his wife, the former Esther Handley, hit him over the head with a liniment bottle when he returned home late with lipstick on his collar.

Late in his career, Turner was on the verge of getting a second crack at the welterweight title after out-pointing future title-holder Virgil Akins. They met on Sept. 18, 1957, in Atlantic City during the National Convention of the American Legion with the winner promised a match with Vince Martinez for the title vacated by Carmen Basilio who had left the division to campaign as a middleweight.

Turner and Martinez clashed on Jan. 15, 1958 before an SRO crowd of 7,120 at the Philadelphia Arena. But this being boxing where promises are often fool’s gold, there was no title at stake. A tug-of-war between the New York State Athletic Commission and the National Boxing Association produced a compromise of sorts, a four-man tournament that reduced the Turner-Martinez fight to a semifinal. And for Gil Turner, that proved to be a moot point. The crafty Martinez out-pointed him, winning a majority decision that most in attendance thought should have been unanimous.

Turner soldiered on for five more fights, leaving the sport at age 28 after suffering a 10-round shutout at the hands of perennial contender Del Flanagan, a man he had defeated in each of their two previous bouts. “In true Philadelphia style,” writes British boxing writer Peter Silkov, “[Gil Turner] blazed bright, and burnt out young.”

—

In retirement, Gil Turner fell off the map. A rare sighting of him in the papers came in May of 1962 when an outburst in a Philadelphia courtroom prompted the presiding judge to order a psychiatric exam. Turner was charged with striking a policeman as he was being removed from his cell for fingerprinting. He was being held on a gambling charge after vice detectives raided his apartment and found a dice game in progress. (The charges were dropped.)

Turner died on May 13, 1996, and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Enter John DiSanto.

John DiSanto in a 2006 photo

In 2004, DiSanto founded the website PhillyBoxingHistory.com to preserve the memory of the fighters, many long forgotten, who contributed to Philadelphia’s rich boxing tradition. In his research, DiSanto discovered that many were buried in unmarked graves and he set about to rectify the situation. Through his efforts, and at considerable expense, tombstones have been placed over the graves of Matthew Saad Muhammad, Tyrone Everett, Gypsy Joe Harris, Garnet “Sugar” Hart, and Eddie Cool, the latter a Depression-era featherweight. In recent weeks, DiSanto renewed a crusade to add Gil Turner to that list.

In addition to dying without an estate to cover burial expenses, most of the recipients had lifestyle problems in retirement that eroded any sympathy for them, but DiSanto is not judgmental. Erratic behavior is all too common among men who once had jobs that involved taking punches to the head.

The first reporters to interview Gil Turner were impressed by the demeanor of the young man who grew up in North Philly in one of the city’s worst neighborhoods, but in a stable home. They described him as a class act, a person, mature beyond his years, who respected his elders and never bad-mouthed his opponents. Because we know little about Turner in his post-fighting days, this is the Gil Turner that we should remember.

“Even the smallest donation helps us make this goal a reality,” says John DiSanto of his latest project to erect a headstone over the grave of Gil Turner. He can be reached at johndisanto@comcast.net

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)