Featured Articles

John Joe Nevin Fought For More Than A Medal

“Can I have four tickets to whatever event is on here now?” asks a German tourist at the ticket office outside London’s Excel Arena.

“Can I have four tickets to whatever event is on here now?” asks a German tourist at the ticket office outside London’s Excel Arena.

“You mean the boxing? Not a chance, mate,” says the man behind the counter, unable to withhold a smirk. Tickets for the 10,000 seat arena are sold out for the Olympic semi-finals, just as they have been every day over the last two weeks.

Difficulties in viewing the competition aren’t limited to London. Across the sea in the Irish town of Mullingar the family of John Joe Nevin gather to watch the boxer in a local pub moments before he meets Cuba’s Lázaro Álvarez in the Olympic bantamweight silver medal contest. They enter the pub but are told to leave. Arguments ensue, accusations are made. Other pubs in the town shut their doors, not wanting the group’s business. Nevin’s family have to venture six miles outside Mullingar to find somewhere that will let them in to watch the bout.

***

It’s been a difficult few years for Ireland. The once heralded “Celtic Tiger” economy dramatically collapsed in 2008, with the nation subsequently forced to accept external financial aid as thousands of young jobseekers emigrate in search of work. The lack of opportunity in people’s lives has stymied their own ambition and seen an increased unity behind the national sporting teams; essentially anything that can distract from the perpetual headlines detailing rising unemployment and economic stagnation.

The teams haven’t obliged, with the much-hyped rugby squad underperforming at the world cup late last year, while the soccer team was pitifully out-classed this summer at its first appearance in the European championships in 24 years. Those disappointments left a lot of scope for the Olympic boxers to capture public attention. Before London 2012, Ireland had won a total of four medals in all sports over the last three Games, and three of them were in boxing. Katie Taylor duly obliged public expectation and won the female competition and John Joe Nevin was seen as the best hope of emulating Michael Carruth to win Ireland’s first male gold since 1992.

John Waters of the Irish Times recently explained Ireland’s obsession with sport: “An Olympic medal, or a creditable appearance by an Irish team in the finals of some international competition, is proposed as something fundamental, rather than a mere passing cause for celebration. And it is indeed as if such successes occur to provide a kind of hope by proxy for the entire population, for whom more enduring forms of hope are nowadays culturally inaccessible.”

Nevin, 23, has been regarded as the best Irish male amateur since 2008. After being eliminated in his second contest at the Beijing Games, he later won two bronze medals at world championships. A relaxed counter-puncher in the ring, he boxes with a confident style, typically avoiding punches by a deft move of the head, putting himself in a position with strike with a sharp right cross. Yet in the months leading up to London his performances slumped. He was beaten by opponents that should have been routine tune-ups. Several members of the Irish team said the pressure was getting to Nevin. “He told me a few months ago that he wanted to pull out of the Games,” said 2008 Olympic silver medallist Kenny Egan. “He didn’t want to go through with it.”

In addition to dealing with the expectations of a success-starved nation, Nevin’s distinct heritage has brought additional difficulties. He is part of the Travelling community, a traditionally nomadic group considered a distinct ethnic minority in Ireland and Great Britain. The Traveller population in Ireland nears 30,000 and in recent years the group have become more integrated into the broader society, with many living in fixed houses and attending public schools. But the relationship between the communities is uneasy. The Traveller culture suffers from stigmas of violence and crime not helped by the portrayal of their idiosyncratic customs with a voyeuristic curiosity in the mainstream media via “exposé” documentaries on bare-knuckle boxing and reality shows like My Big Fat Gypsy Wedding. As with many minorities, the actions of a few taint an entire community.

Few Travellers have been depicted as positive role models. Former boxer Francis Barrett is the most notable exception. Barrett competed for Ireland at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics and the popularity of his story saw him carry the nation’s flag at the Games’ opening ceremony. The gesture was expected to be a major breakthrough moment for the Travelling community. It wasn’t.

“Six weeks after I came back from the Olympic Games, I was turned away from a bar,” recalled Barrett. “I wouldn't say all Travellers are good. Some cause fights, drunken arguments and break places up, but you should not paint them all with the one brush.”

Sixteen years later Nevin’s family had to journey miles outside their hometown to find a public place that would allow them watch their next of kin approach the zenith of his vocation.

“It is wrong,” said Barrett of the apparent discrimination that faced Nevin’s family on the day of his semi-final bout. “If African or Polish people were not served in pubs because of their nationality there would be big trouble and so there should be. It is a disgrace that these pub landlords closed the door of the pubs. By rights they should be proud; John Joe is fighting for his country.”

Nevin’s cousin Martin said John Joe learned of the situation just moments before his contest with Cuba’s Álvarez. “He really took it personally,” claimed Martin. “He asked me was there a problem with him, whether the local people unhappy with his performance at the Olympics. He was really upset because he thought it was about him. He was in tears.”

But the anguish seemed to stir Nevin into the greatest performance of his career, culminating in a 19-14 points win over Álvarez. Nevin became the first Traveller to win an Olympic medal and expectations were high that he could beat Great Britain’s Luke Campbell to win gold the following Saturday night.

***

The strains of Queen’s “We Will Rock You” bring the crowd to its feet, with John Joe Nevin emerging into the arena first. Significantly less Irish fans are here than for Katie Taylor’s bouts earlier in the week, but those in attendance do their best to make themselves heard. Decked out in red vest and shorts, Nevin bounces on his toes, wearing a broad smile. Accompanied by coaches Billy Walsh and Zaur Anita in resplendent green tracksuits, Nevin raises his gloves to the crowd, signalling a contentment with the task in hand. He may be genuinely at ease, or putting on a front, but in a few minutes it won’t matter; attempts at illusion are quickly dispelled in the ring. Bounding up the steps and through the ropes, Nevin skirts the ring’s perimeter before briefly settling in front of his opponent’s corner where he wipes the soles of his shoes on the canvas as if marking his territory. He moves to his own red corner where Walsh affixes a headguard that will protect from superficial injury, but can do little to diffuse the concussive blows of an Olympic opponent.

As Luke Campbell comes into view the noise of the crowd reaches new decibels. The Irish fans gallantly respond with soccer-style chants but are soon drowned out by the locals’ booming repetition of “Campbell, Campbell”. There’s sincerity in Campbell’s approach; head down, he walks quickly with purpose to the ring. His face expressionless, he seems tense, as he should be. At the foot of the ring’s steps he jumps in the air, bringing his knees into his chest in an effort to shake out the nerves that likely make his legs feel like lead.

With introductions underway, the boxers prepare for nine minutes of combat dissected into three rounds in which they hope the judges at ringside will acknowledge every punch they land by pressing an electronic button.

As the round starts Nevin, boxing from an orthodox stance, immediately looks to assert himself by stepping firmly onto his southpaw opponent’s lead foot. He does this several more times, but the referee is quick to issue a caution. Campbell, the taller, rangier boxer, seeks to keep the fight at a distance by constantly moving while launching long, straight punches. Nevin has a sturdier look about him and is prepared to stand flat-footed and lean away before quickly throwing looping right hands. Each man tries to impose his will, hoping to draw the other away from their well-rehearsed strategy.

Billy Walsh sits ringside gulping back water. He’s fidgeting, crossing his legs, cracking knuckles, trying to subdue the adrenaline. Nevin seems to be almost trying too hard, with his eagerness to score compelling him move forward instead of boxing off the back foot. He gets caught by Campbell’s long right hand through the round and as the bell sounds the Irishman is behind 5-3.

In the second, Walsh forgets his restraint, snapping out right hand– left hook combinations. Nevin lands a solid right and Walsh leaps off his chair, pumping his fist. The punch gives Nevin momentum and by round’s end the deficit is reduced at 8-9. Behind by one score, Nevin knows he has to press the action. Desperation leads him to chase Campbell, who midway through the round smoothly steps back and catches an onrushing Nevin with a hard right hook. Nevin falls to the canvas. He recovers his senses quickly and unleashes a flurry of combinations through the remainder of the round. Some blows appear to connect, while others are deflected off Campbell’s gangly arms.

As the contest ends Nevin stands in the ring’s center. He blesses himself and looks skyward, praying that the oft-erratic scoring will go in his favour. When the final result of 14-11 is announced for Campbell there are no complaints from the Irish contingent. As the arena lets out a thunderous roar, Nevin fulfils the obligatory congratulations for his triumphant opponent. After leaving the ring, Walsh puts a red robe onto Nevin’s listless body and a white towel over his bowed head.

Nearly half an hour later the boxers are summoned back into the ring for the medal ceremony. Nevin is cleaned-up and dressed in a green Irish tracksuit, but his face remains solemn. Just three punches landed or blocked and he could be standing up where Campbell is, allowing the Irish fans to wave their tricolours to “Amhrán na bhFiann” instead of enduring the deep bellows of “God Save the Queen”.

After descending from the podium the boxers make their way from the ring. Nevin gives Campbell a final pat on the shoulder, but it goes unnoticed as the gold medallist is quickly surrounded by a horde of cameras and reporters. Nevin circumvents the gathering toward a small gathering of Irish media. He says a few words, has his picture taken with the tricolour and walks alone into the bowels of the arena.

***

Back in Mullingar applause resonates around the town center where a crowd of 5,000 [one quarter of the town’s population] has just watched the ceremony on a specially erected 13-foot outdoor screen. While Nevin’s immediate family decided to stay away from the town, many of his extended clan are among the spectators. Yet it is difficult to tell people apart; most blend together in a sea of green and gold. The town center belongs to no one and everyone, each person sharing common ground without disagreement or unrest; a community brought together by a young man’s sporting endeavours.

“I’m glad of Mullingar, what they done for John Joe,” said Nevin’s mother Winnie later that night. “I was watching it on television and there was a queer [astonishing] atmosphere in Mullingar at the Market Square, and fair play to the Mullingar people, but not the pubs, the pubs is a disgrace.”

Around the country 1.2 of the 5 million population tuned into the bout on television, with many more venturing to pubs and other pubic venues. The following Monday an estimated 7,000 people lined the streets of Mullingar to welcome back Nevin as he was paraded on an open-top bus.

“Today it’s a dream come true for me to come back and get represented by such a big crowd,” said Nevin at his homecoming. “It’s great to see all my family here. I was devastated to lose the final but saying that, I’ve gotten so far and a month ago I was talking about not going [to the Olympics].”

That Nevin didn’t win gold is insignificant. He ultimately absorbed the expectation of country and community and as part of the most successful boxing team in Ireland’s Olympic history he showed that the small island can still compete with the best. Whether rich or poor, Traveller or settled, few can be untouched by the success of the Olympian that runs on their town’s roads, trains at a nearby gym and breathes the same damp Irish air.

Nevin’s success won’t see the masses flock to boxing clubs, nor will it wholly change broad perceptions of the Travelling community. But when the youth of Ireland are discouraged by the shortage of opportunity or fearing immigration, maybe in the coming months they will think of how Nevin had his own setbacks before he achieved on the grandest stage. He has provided a flicker of inspiration to a generation in danger of losing the ability to dream.

Ronan Keenan can be contacted at ronankeenan@yahoo.com

Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 326: A Hectic Boxing Week in L.A.

The Los Angeles area is packed with boxing.

Japan’s Mizuki “Mimi” Hiruta, Ukraine’s Serhii Bohachuk, and the indefatigable Jake Paul are all in the Los Angeles area this week.

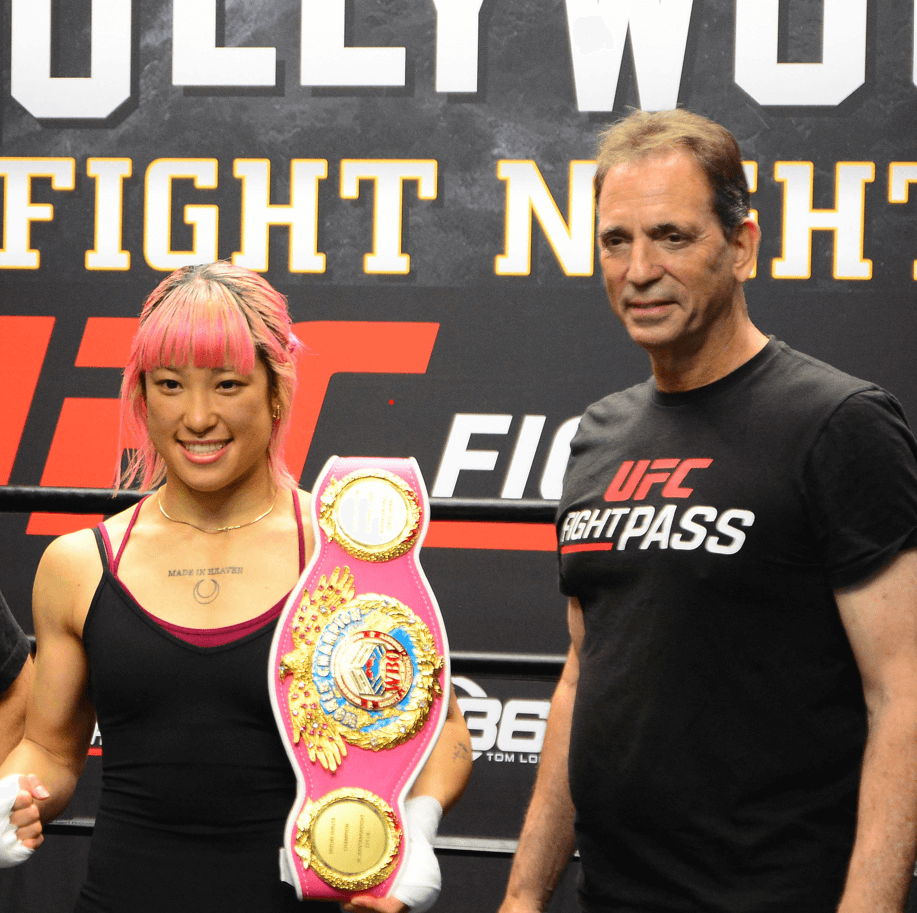

First, Hiruta (7-0, 2 KOs) defends the WBO super flyweight title against Argentina’s Carla Merino on Saturday May 17, at Commerce Casino. The 360 Boxing Promotions card will be streamed on UFC Fight Pass.

Voted Japan’s best female fighter, Hiruta faces a stiff challenge from Merino who traveled thousands of miles from Cordoba.

360 Promotions is one of the top promotions especially when it comes to presenting female prizefighting. Two of their other female fighters, Lupe Medina and Jocelyn Camarillo, will also be fighting on Saturday.

They are not only promoting female fighters. They have several top male champions including Bohachuk and Omar “Trinidad performing this Saturday.

Don’t miss this show at Commerce Casino.

“This card is one of the deepest cards we’ve promoted in Southern California which has been proven by the rush for tickets and the wealth of media interest. Serhii, Omar and Mizuki are three of the top fighters in their respective weight classes and it’s a great opportunity for fans to see a full night of action,” said Tom Loeffler of 360 Promotions.

Jake and Chavez Jr. in L.A.

Jake Paul took time off from training in Puerto Rico to visit Los Angeles to hype his upcoming fight against former world champion Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. next month.

“The fans have wanted to see this, and I want to continue to elevate and raise the level of my opponents,” said Paul, 28. “This is a former world champion, and he has an amazing resume following in his dad’s footsteps.”

Paul, who co-owns Most Valuable Promotions with Nakisa Bidarian, last staged a wildly successful boxing card that included Amanda Serrano versus Katie Taylor and of course his own fight with Mike Tyson.

It set records for viewing according to Netflix with an estimated 108 million views.

Paul (11-1, 7 KOs) is set to face Chavez (54-6-1, 34 KOs) in a cruiserweight battle at the Honda Center in Anaheim, Calif. on June 28. DAZN pay-per-view will stream the Golden Boy Promotions and MVP fight card that includes the return of Holly Holm to the boxing world after years in MMA.

No one should underestimate Paul who does have crackling power in his fists. He is for real and at 28, is in the prime of his boxing career.

Yes, he is a social influencer who got into boxing with no amateur background, but since he engaged fully into the sport, Paul has shown remarkable improvement in all areas.

Is he perfect? Of course not.

But power is the one attribute that can neutralize any faults and Paul does have real power. I witnessed it when I first saw him in the prize ring in Los Angeles many years ago.

Chavez, 39, the son of Mexico’s great Julio Cesar Chavez, is not as good as his father but was talented enough to win a world title and hold it until 2012 when he was edged by Sergio Martinez.

The son of Chavez last fought this past July when he defeated former UFC fighter Uriah Hall in a boxing match held in Florida. He has been seeking a match with Paul for years and finally he got it.

“I need to prepare 100%. This is an interesting fight. It might not be easy, but I’m going to do the best I can to be the best person I am, but I think I’m going to take him,” said Chavez.

Paul was not shy about Chavez’s talent.

“This is his toughest fight to date, and I’m going to embarrass him and make him quit like he always does,” said Paul about Chavez Jr. “I’m going to expose and embarrass him. He’s the embarrassment of Mexico. Mexico doesn’t even claim him, and he’s going to get exposed on June 28.”

Also on the same fight card is unified cruiserweight champion Gilberto “Zurdo” Ramirez (47-1, 30 KOs) who defends the WBA and WBO titles against Yuniel Dorticos (27-2, 25 KOs).

In a surprising addition, former boxing champion Holm returns to the boxing ring after 12 years away from the sport. Can she still fight?

Holm (33-2-3, 9 KOs) meets Mexico’s Yolanda Vega (10-0, 1 KO) in a lightweight fight scheduled for 10 rounds. Holm is 43 and Vega is 29. Many eyes will be looking to see the return of Holm who was recently voted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Wild Card Honored by L.A. City

A formal presentation by the Los Angeles City Council to honor the 30th anniversary of the Wild Card Boxing Club takes place on Sunday May 18, at 1:30 p.m. The ceremony takes place in front of the Wild Card located at 1123 Vine Street, Hollywood 90038.

Along with city councilmembers will be a number of the top first responder officials.

Championing Mental Health

A star-studded broadcast team comprised of Al Bernstein, Corey Erdman and Lupe Contreras will announce the boxing event called “Championing Mental Health” card on Thursday May 22, at the Avalon Theater. DAZN will stream the Bash Boxing card live.

Among those fighting are Vic Pasillas, Jessie Mandapat and Ricardo Ruvalcaba.

For more information including tickets go to www.555media.com/tickets.

Fights to Watch

Sat. UFC Fight Pass 7 p.m. Mizuki Hiruta (7-0) vs Carla Merina (16-2).

Thurs. DAZN 7 p.m. Vic Pasillas (17-1) vs Carlos Jackson (20-2).

Mimi Hiruta / Tom Loeffler photo credit: Al Applerose

Featured Articles

Sam Goodman and Eccentric Harry Garside Score Wins on a Wednesday Card in Sydney

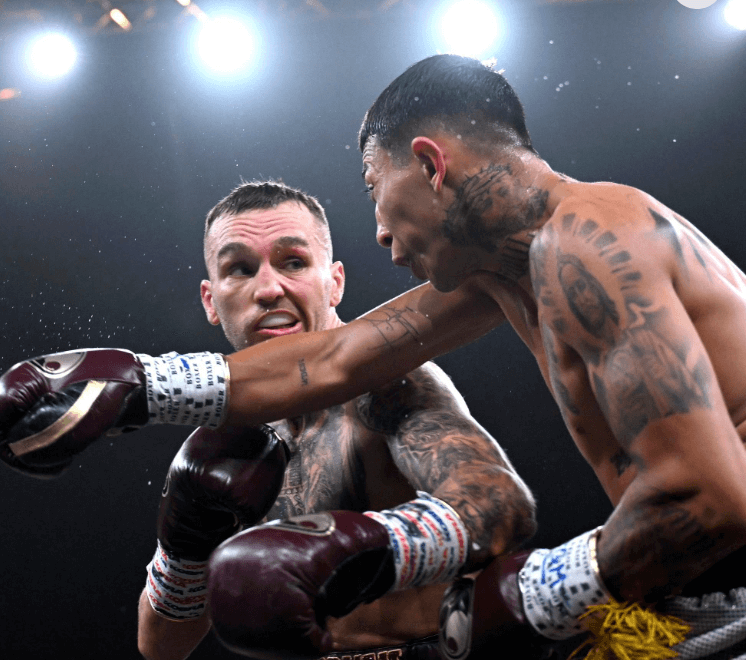

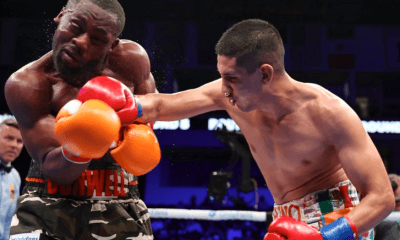

Australian junior featherweight Sam Goodman, ranked #1 by the IBF and #2 by the WBO, returned to the ring today in Sydney, NSW, and advanced his record to 20-0 (8) with a unanimous 10-round decision over Mexican import Cesar Vaca (19-2). This was Goodman’s first fight since July of last year. In the interim, he twice lost out on lucrative dates with Japanese superstar Naoya Inoue. Both fell out because of cuts that Goodman suffered in sparring.

Goodman was cut again today and in two places – below his left eye in the eighth and above his right eye in the ninth, the latter the result of an accidental head butt – but by then he had the bout firmly in control, albeit the match wasn’t quite as one-sided as the scores (100-90, 99-91, 99-92) suggested. Vaca, from Guadalajara, was making his first start outside his native country.

Goodman, whose signature win was a split decision over the previously undefeated American fighter Ra’eese Aleem, is handled by the Rose brothers — George, Trent, and Matt — who also handle the Tszyu brothers, Tim and Nikita, and two-time Olympian (and 2021 bronze medalist) Harry Garside who appeared in the semi-wind-up.

Harry Garside

Harry Garside

A junior welterweight from a suburb of Melbourne, Garside, 27, is an interesting character. A plumber by trade who has studied ballet, he occasionally shows up at formal gatherings wearing a dress.

Garside improved to 4-0 (3 KOs) as a pro when the referee stopped his contest with countryman Charlie Bell after five frames, deciding that Bell had taken enough punishment. It was a controversial call although Garside — who fought the last four rounds with a cut over his left eye from a clash of heads in the opening frame – was comfortably ahead on the cards.

Heavyweights

In a slobberknocker being hailed as a shoo-in for the Australian domestic Fight of the Year, 34-year-old bruisers Stevan Ivic and Toese Vousiutu took turns battering each other for 10 brutal rounds. It was a miracle that both were still standing at the final bell. A Brisbane firefighter recognized as the heavyweight champion of Australia, Ivic (7-0-1, 2 KOs) prevailed on scores of 96-94 and 96-93 twice. Melbourne’s Vousiuto falls to 8-2.

Tim Tsyzu.

The oddsmakers have installed Tim Tszyu a small favorite (minus-135ish) to avenge his loss to Sebastian Fundora when they tangle on Sunday, July 20, at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

Their first meeting took place in this same ring on March 30 of last year. Fundora, subbing for Keith Thurman, saddled Tszyu with his first defeat, taking away the Aussie’s WBO 154-pound world title while adding the vacant WBC belt to his dossier. The verdict was split but fair. Tszyu fought the last 11 rounds with a deep cut on his hairline that bled profusely, the result of an errant elbow.

Since that encounter, Tszyu was demolished in three rounds by Bakhram Murtazaliev in Orlando and rebounded with a fourth-round stoppage of Joey Spencer in Newcastle, NSW. Fundora has been to post one time, successfully defending his belts with a dominant fourth-round stoppage of Chordale Booker.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Thomas Hauser’s Literary Notes: Johnny Greaves Tells a Sad Tale

Johnny Greaves was a professional loser. He had one hundred professional fights between 2007 and 2013, lost 96 of them, scored one knockout, and was stopped short of the distance twelve times. There was no subtlety in how his role was explained to him: “Look, Johnny; professional boxing works two ways. You’re either a ticket-seller and make money for the promoter, in which case you get to win fights. If you don’t sell tickets but can look after yourself a bit, you become an opponent and you fight to lose.”

By losing, he could make upwards of one thousand pounds for a night‘s work.

Greaves grew up with an alcoholic father who beat his children and wife. Johnny learned how to survive the beatings, which is what his career as a fighter would become. He was a scared, angry, often violent child who was expelled from school and found solace in alcohol and drugs.

The fighters Greaves lost to in the pros ran the gamut from inept local favorites to future champions Liam Walsh, Anthony Crolla, Lee Selby, Gavin Rees, and Jack Catterall. Alcohol and drugs remained constants in his life. He fought after drinking, smoking weed, and snorting cocaine on the night before – and sometimes on the day of – a fight. On multiple occasions, he came close to committing suicide. His goal in boxing ultimately became to have one hundred professional fights.

On rare occasions, two professional losers – “journeymen,” they’re called in The UK – are matched against each other. That was how Greaves got three of the four wins on his ledger. On September 29, 2013, he fought the one hundredth and final fight of his career against Dan Carr in London’s famed York Hall. Carr had a 2-42-2 ring record and would finish his career with three wins in ninety outings. Greaves-Carr was a fight that Johnny could win. He emerged triumphant on a four-round decision.

The Johnny Greaves Story, told by Greaves with the help of Adam Darke (Pitch Publishing) tells the whole sordid tale. Some of Greaves’s thoughts follow:

* “We all knew why we were there, and it wasn’t to win. The home fighters were the guys who had sold all the tickets and were deemed to have some talent. We were the scum. We knew our role. Give some young prospect a bit of a workout, keep out of the way of any big shots, lose on points but take home a wedge of cash, and fight again next week.”

* “If you fought too hard and won, then you wouldn’t get booked for any more shows. If you swung for the trees and got cut or knocked out, then you couldn’t fight for another 28 days. So what were you supposed to do? The answer was to LOOK like you were trying to win but be clever in the process. Slip and move, feint, throw little shots that were rangefinders, hold on, waste time. There was an art to this game, and I was quickly learning what a cynical business it was.”

* “The unknown for the journeyman was always how good your opponent might be. He could be a future world champion. Or he might be some hyped-up nightclub bouncer with a big following who was making lots of money for the promoter.”

* “No matter how well I fought, I wasn’t going to be getting any decisions. These fights weren’t scored fairly. The referees and judges understood who the paymasters were and they played the game. What was the point of having a go and being the best version of you if nobody was going to recognize or reward it?”

* “When I first stepped into the professional arena, I believed I was tough. believed that nobody could stop me. But fight by fight, those ideas were being challenged and broken down. Once you know that you can be hurt, dropped and knocked out, you’re never quite the same fighter.”

* “I had started off with a dream, an idea of what boxing was and what it would do for me. It was going to be a place where I could prove my toughness. A place that I could escape to and be someone else for a while. For a while, boxing was that place. But it wore me down to the point that I stopped caring. I’d grown sick and tired of it all. I wished that I could feel pride at what I’d achieved. But most of the time, I just felt like a loser.”

* “The fights were getting much more difficult, the damage to my body and my psyche taking longer and longer to repair after each defeat. I was putting myself in more and more danger with each passing fight. I was getting hurt more often and stopped more regularly. Even with the 28-day [suspensions], I didn’t have time to heal. I was staggering from one fight to the next and picking up more injuries along the way.”

* “I was losing my toughness and resilience. When that’s all you’ve ever had, it’s a hard thing to accept. Drink and drugs had always been present in my life. But now they became a regular part of my pre-fight preparation. It helped to shut out the fear and quieted the thoughts and worries that I shouldn’t be doing this anymore.”

* “My body was broken. My hands were constantly sore with blisters and cuts. I had early arthritis in my hip and my teeth were a mess. I looked an absolute state and inside I felt worse. But I couldn’t stop fighting yet. Not before the 100.”

* “I had abused myself time after time and stood in front of better men, taking a beating when I could have been sensible and covered up. At the start, I was rarely dropped or stopped. Now it was becoming a regular part of the game. Most of the guys I was facing were a lot better than me. This was mainly about survival.”

* “Was my brain f***ed from taking too many punches? I knew it was, to be honest. I could feel my speech changing and memory going. I was mentally unwell and shouldn’t have been fighting but the promoters didn’t care. Johnny Greaves was still a good booking. Maybe an even better one now that he might get knocked out.”

* “Nobody gave a f*** about me and whether I lived or died. I didn’t care about that much either. But the thought of being humiliated, knocked out in front of all those people; that was worse than the thought of dying. The idea of being exposed for what I was – a nobody.”

* “I was a miserable bastard in real life. A depressive downbeat mouthy little f***er. Everything I’ve done has been to mask the feeling that I’m worthless. That I have no value. The drinks and the drugs just helped me to forget that for a while. I still frighten myself a lot. My thoughts scare me. Do I really want to be here for the next thirty or forty years? I don’t know. If suicide wasn’t so impactful on people around you, I would have taken that leap. I don’t enjoy life and never have.”

So . . . Any questions?

****

Steve Albert was Showtime’s blow-by-blow commentator for two decades. But his reach extended far beyond boxing.

Albert’s sojourn through professional sports began in high school when he was a ball boy for the New York Knicks. Over the years, he was behind the microphone for more than a dozen teams in eleven leagues including four NBA franchises.

Putting the length of that trajectory in perspective . . . As a ballboy, Steve handed bottles of water and towels to a Knicks back-up forward named Phil Jackson. Later, they worked together as commentators for the New Jersey Nets. Then Steve provided the soundtrack for some of Jackson’s triumphs when he won eleven NBA championships as head coach of the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers.

It’s also a matter of record that Steve’s oldest brother, Marv, was arguably the greatest play-by-play announcer in NBA history. And brother Al enjoyed a successful career behind the microphone after playing professional hockey.

Now Steve has written a memoir titled A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Broadcast Booth. Those who know him know that Steve doesn’t like to say bad things about people. And he doesn’t here. Nor does he delve into the inner workings of sports media or the sports dream machine. The book is largely a collection of lighthearted personal recollections, although there are times when the gravity of boxing forces reflection.

“Fighters were unlike any other professional athletes I had ever encountered,” Albert writes. “Many were products of incomprehensible backgrounds, fiercely tough neighborhoods, ghettos and, in some cases, jungles. Some got into the sport because they were bullied as children. For others, boxing was a means of survival. In many cases, it was an escape from a way of life that most people couldn’t even fathom.”

At one point, Steve recounts a ringside ritual that he followed when he was behind the microphone for Showtime Boxing: “I would precisely line up my trio of beverages – coffee, water, soda – on the far edge of the table closest to the ring apron. Perhaps the best advice I ever received from Ferdie [broadcast partner Ferdie Pacheco] was early on in my blow-by-blow career – ‘Always cover your coffee at ringside with an index card unless you like your coffee with cream, sugar, and blood.’”

Writing about the prelude to the infamous Holyfield-Tyson “bite fight,” Albert recalls, “I remember thinking that Tyson was going to do something unusual that night. I had this sinking feeling in my gut that he was going to pull something exceedingly out of the ordinary. His grousing about Holyfield’s head butts in the first fight added to my concern. [But] nobody could have foreseen what actually happened. Had I opened that broadcast with, ‘Folks, tonight I predict that Mike Tyson will bite off a chunk of Evander Holyfield’s ear,’ some fellas in white coats might have approached me and said, ‘Uh, Steve, could you come with us.'”

And then there’s my favorite line in the book: “I once asked a fighter if he was happily married,” Albert recounts. “He said, ‘Yes, but my wife’s not.'”

“All I ever wanted was to be a sportscaster,” Albert says in closing. “I didn’t always get it right, but I tried to do my job with honesty and integrity. For forty-five years, calling games was my life. I think it all worked out.”

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His next book – The Most Honest Sport: Two More Years Inside Boxing – will be published this month and is available for preorder at:

https://www.amazon.com/Most-Honest-Sport-Inside-Boxing/dp/1955836329

In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 322: Super Welterweight Week in SoCal

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoGabriela Fundora KOs Marilyn Badillo and Perez Upsets Conwell in Oceanside

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks ago‘Krusher’ Kovalev Exits on a Winning Note: TKOs Artur Mann in his ‘Farewell Fight’

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFloyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The First Boxing Writers Assoc. of America Dinner Was Quite the Shindig

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoChris Eubank Jr Outlasts Conor Benn at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoJorge Garcia is the TSS Fighter of the Month for April