Featured Articles

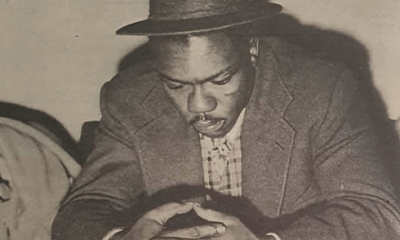

Dreamland Ring Wars: Rocky Marciano vs. Joe Louis: A Peak-for-Peak Analysis

After Rocky Marciano bludgeoned his way to the heavyweight throne in 1952, trainer Charley Goldman reportedly claimed him as his second heavyweight champion. Twelve years earlier, Arturo Godoy used a low-crouching, crowding style that Goldman had taught him to embarrass Joe Louis for fifteen rounds. Godoy lost a split decision, though one judge gave him all but five rounds and many agreed that a new champion should have been crowned that night. “The way he fights he was too hard to hit,” Louis explained. “I could’ve hurt my hands hitting the top of his head.”

“It was my worst fight,” he added.

The rematch was different. Seconds after the opening bell, Godoy rushed into range and Louis planted his feet and fired uppercuts. He positioned his hands inside of the grabbing gloves to find the middle, landing hard shots that sap the spirit. By the seventh round, Godoy could only stumble forward, blinded by his own blood, and Louis knew exactly what to do. He stepped backward and pivoted around with perfect uppercuts and short hooks to bring an artful end to an erstwhile annoyance.

“That was the worst beating I ever gave a man,” he said afterward. The copy editors had a field day coming up with headlines: “Louis, Back in Business as Murder, Inc” said one. “Beating of Godoy Resembled a Bull Fight” said another, more to the point.

CROWD CONTROL

In 1940, while the Louis camp was busy repelling and reanalyzing the odd style of Godoy, sixteen-year-old Rocco Marchegiano was playing baseball at the James Edgar Playground in Brockton, Massachusetts. He was a catcher who batted clean-up. Seven years later, he walked into Stillman’s Gym in Manhattan and clobbered a professional in the second round as Goldman and Godoy watched. Goldman took a look at his tree trunk legs and taught him the same low-crouching, crowding style he had taught Godoy.

By the time Marciano faced a comebacking Louis in 1951, his curious pose would thwack nostalgic to the ex-champion. Louis was thirty-seven and sporting a bald spot that said it all. He was diminished in every category save one—his physical strength, and yet Marciano, despite being outweighed by twenty-five pounds, bulled him to the ropes as easily as Godoy had. Louis was in trouble from the opening bell. He no longer had the timing and reflexes of his youth but with two decades of experience behind him, he could detect patterns and adjust accordingly. In the third round, he began stepping back after punching and Marciano’s fearsome “Suzie Q” became a whistling wind. When he saw Marciano’s habit of slipping to the outside of jabs, he turned his jab over into a hook to meet the predictable slip. Despite these adjustments and despite the fact that he won two of the first five rounds, Louis showed signs of breaking down early.

The fourth round is a snapshot of the quandary that was Marciano. Louis may have won the round on all three judges’ scorecards but the film shows him constantly forced backward and on the defensive. He’s not dictating the pace, he’s not in control; he’s not even the puncher. He’s fighting like a man trying to hold off a crowd—valiant and doomed. At one point he tries to shove Marciano back, but Marciano’s legs are spread and he doesn’t move. And that’s the story: Marciano’s attack was as psychological as it was inexorable. Old Joe survives until the eighth round, when he is unceremoniously knocked through the ropes and lay frozen in time; his head hanging over the ring apron, his right foot dangling daintily on the bottom rope. All at once, cameras explode, the fight is called, and hands appear from everywhere to help the fallen hero.

When great, aging fighters crash down, the world seems to stop. It is they themselves who break the silence; and they tend to say the same thing. “I saw the right coming,” said Louis in the dressing room, “but I couldn’t do anything about it.”

A peaking version of Louis (circa 1939-1941) would have done something about it. He would have fired more counter shots and combinations while managing to avoid most of the overhands that Marciano was slinging throughout the first half of the Fifties. The quandary, though, would remain. Trainer Jack Blackburn, who died in 1942, made critical adjustments for the Godoy rematch in 1940; however, it’s a stretch to assume these adjustments would have been successful against Marciano. Godoy weakened by the seventh round. Marciano wouldn’t weaken. Unlikely to ever lose a test of wills, he seemed to get stronger as fights wore on and opponents wore out. Louis would have been faster and with Blackburn in his corner, better informed, and yet a good handicapper would set odds against him anyway.

ZOOMING IN

As technically proficient as he was at every range, Louis would not be the dominant force in close. Marciano had a way of leaning into his opponent like some fabled strong man pushing a boulder over a cliff, or a fighter over a hill. He’d use his arms as barriers to prevent escape and lock his gloves inside the crook of the arm to stop offense —all the while pushing, pushing forward. Louis did not and would not try to outmuscle Marciano; the trainer who built him insisted on economy of motion and cautioned against wasting energy. This explains why Louis can be seen with his back on the ropes punching with discipline or spinning out against Godoy; he was a machine programmed for a strict, one-track purpose. He does not wrestle. Against Marciano, he would allow himself to be moved backward to the ropes and squared up, which would make him a wider target and compromise his offense. It’s a dangerous concession.

Louis’s best chance would be to command center-ring while taking full steps backwards. He’d have to rely on his balance to make those steps launching pads for counters, and those counters should be horizontal instead of vertical. In other words, uppercuts, though lethal when thrown by such a puncher, are not advisable here. They tend to leave a rather large window unshuttered and Marciano knew how to put a rock through it: he anticipated them and was ever-ready to counter over the top. Louis’s willingness to open up on Godoy to “bring him up” from his crouch would be riskier against Marciano, who was at his best in exchanges —particularly when the chin he was aiming for was something less than his own. However, Marciano was less prepared for short left hooks. With his head low and his right hand positioned more to the front of his chin, he had trouble seeing and blocking them as he pushed forward. Louis would want to pivot off the hook to his left to get outside of the looping right, set up his own straight right, and work in a circle.

Zeroing-in on Marciano is easier said than done. Besides presenting a low target and burrowing under stand-up fighters and their line of fire, he was given an array of subtle skills that could only have come from one of boxing’s true masterminds. He was taught to anticipate the return after punching and move his head automatically and accordingly to get into position to counter the counter shot. He learned to ride incoming jabs by shifting his weight backward onto his right leg and then spring in with a counter that felt like a kitchen sink. Awkward, short-armed, and prone to throw wildly from too far away, Goldman taught him to shift his weight forward with the momentum of a missed shot and then follow up with something harder from somewhere closer. This is better than mere balance-recovery because Marciano’s missed shots—his mistakes—could conceivably double the impact of what was coming next.

Goldman reminded everyone that Marciano hit considerably harder than Godoy. “The great thing about this kid is he’s got leverage,” he told A.J. Liebling. “He takes a good punch and he’s got the equalizers.” Joe Rein watched Marciano spar at Stillman’s. “To see him punch,” he told Sports Illustrated, “it was like he was lobbing paving stones.” Indeed, that deep weave wasn’t simply to get under an opponent’s offense; it powered-up his own enough to send much larger men reeling backward. It’s a critical point. Before the opponent could recover either his wits or his balance, Marciano would be at his chest grinding away and throwing right hooks to the flank and left uppercuts to the sternum. Few men anywhere near his weight would have the strength to resist his low-centered power thrusts and fewer still would have the speed of foot to step back out of range, counter, and then spin off before he pinned them on the ropes.

Joe Louis isn’t among them. He was not stronger than Marciano and his mobility was efficient, deliberate—and not fast enough. He was a thinking fighter who worked off the jab and tried to blast through the back of an opponent’s head. It made for a compelling spectacle when he was stalking opponents and closing the distance on his own terms, but Marciano would concede nothing. Marciano was too stingy a fighter to allow either room to punch or time to mull things over. “It is very hard to think,” cutman Freddie Brown quipped, “when you are getting your brains knocked out.”

Boxing historians and fans watch clips of Louis’s knockouts, compelling spectacles all, and are rightfully astonished. Many are astonished enough to deny an odds-busting truth of boxing: Styles make fights. To be sure, Louis had the ability to handle almost any style. He could be counted on to overcome modern giants, flatten punchers, and, contrary to popular myth, search out and destroy mobile boxers. “If he runs, will you chase him?” Louis was asked before his rematch with Billy Conn. His classic response (“He can run, but he can’t hide”) isn’t just a good cutline, it rings with truth. Louis had trouble with one style in particular and he knew it: “I had a bad weakness I kept hid throughout my career. I didn’t like to be crowded, and Marciano always crowded his opponents. That’s why I say I could never have beaten him.” For a man who said Muhammad Ali would have been just another “bum of the month,” this admission reveals much.

Peak-for-peak, Rocky Marciano should be favored to defeat Joe Louis by late round stoppage.

X FACTORS

Boxing is a party often crashed by unforeseen circumstances. There are several that could skew or even reverse the result of this match, including the following:

1) The timing of the bout. After his first clash with Godoy, it was plain to everyone that Louis was unsure of just how to penetrate or cope with the unfamiliar style in front of him. “We found out this one got to be handled different,” Blackburn admitted. “We know now.” Marciano’s attack only appeared to be similar to Godoy’s; it was far more debilitating and allowed no learning curve. If a prime Louis fights Marciano and isn’t sharp, he loses badly. If he fights him at any point on or before the night he first faced Godoy, his chance of winning would be further diminished.

2) The referee. If the referee finds Marciano’s inside maneuvering and mauling tactics distasteful enough to break them up, then Louis will have a distinct advantage. Marciano needs the inside to grind Louis down. Although the belief here is that he’d be landing heavily on the way in, he would do most of the damage once he was there. He would be outpunched from the other ranges.

3) Cuts. A friend from Brockton named Charlie Petti remembered the winter of 1950-51 when the temperature in the city dropped to ten below zero for days. Marciano ran his eight miles faithfully anyway, and said “the cold air toughens my skin and I won’t cut so easy.” Louis’s corkscrew bombs made a red mess of Godoy’s face. If Louis manages to do the same to Marciano, there is a considerable risk that the fight would be stopped despite the preventative efforts of the fanatical fighter and the quick-fix coagulants of his cut man.

4) A perfect shot, followed by a series. Marciano’s fabled endurance, chin, and conditioning are true assets, but Louis was arguably the greatest finisher in heavyweight history. If Marciano makes enough mistakes to get himself badly hurt, no intangible is certain to save him.

____________________

Matt McGrain, a boxing historian and analyst of the first order, provided a welcome impetus for this analysis with a gentleman’s challenge. References include “’Godoy Just a Clown’, Says Joe” by Art Carter in The Afro American, 2/17/40; “Remembering the Champ,” by Charlie Petti, 1970; “Weill Almost Missed Out Entirely on His Meal Ticket —Marciano” by Evans Kirkby, Milwaukee Journal, 8/25/68; AP 10/27/51; Charley Goldman and Freddie Brown quotes as told to Liebling in his essay, “Charles II,” in The Sweet Science.

Special thanks to Cameron Burns, the talent behind the graphic opening this essay. He can be reached at cameronburns13@gmail.com.

Springs Toledo can be reached at scalinatella@hotmail.com.

Featured Articles

Chris Eubank Jr Outlasts Conor Benn at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

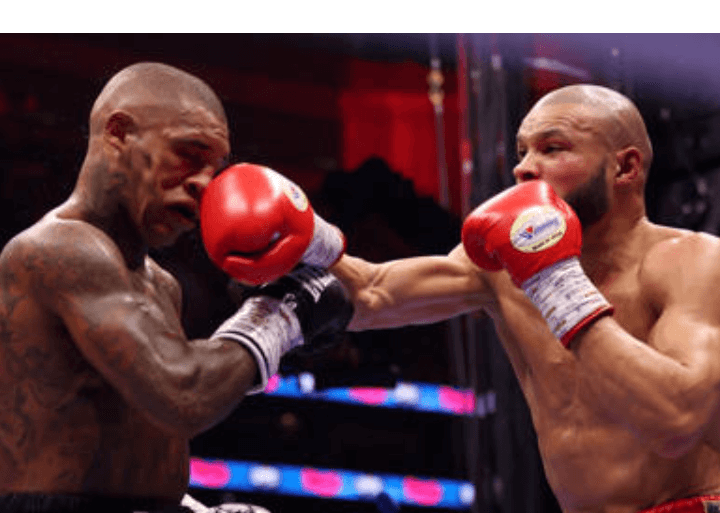

Feudal bragging rights belong to Chris Eubank Jr. who out-lasted Conor Benn to

emerge victorious by unanimous decision in a non-title middleweight match held in

London on Saturday.

Fighting for their family heritage Eubank (35-3, 26 KOs) and Benn (23-1, 14 KOs)

continued the battle between families started 35 years ago by their fathers at Tottenham

Hotspur Stadium.

More than 65,000 fans attended.

Though Eubank Jr. had a weight and height advantage and a record of smashing his

way to victory via knockout, he had problems hurting the quicker and more agile Benn.

And though Benn had the advantage of moving up two weight divisions and forcing

Eubank to fight under a catch weight, the move did not weaken him much.

Instead, British fans and boxing fans across the world saw the two family rivals pummel

each other for all 12 rounds. Neither was able to gain separation.

Eubank looked physically bigger and used a ramming left jab to connect early in the

fight. Benn immediately showed off his speed advantage and surprised many with his

ability to absorb a big blow.Chris Eubank Jr Outlasts Conor Benn at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

Benn scrambled around with his quickness and agility and scored often with bigcounters.

It took him a few rounds to stop overextending himself while delivering power shots.

In the third round Benn staggered Eubank with a left hook but was unable to follow up

against the dangerous middleweight who roared back with flurries of blows.

Eubank was methodic in his approach always moving forward, always using his weight

advantage via the shoulder to force Benn backward. The smaller Benn rocketed

overhand rights and was partly successful but not enough to force Eubank to retreat.

In the seventh round a right uppercut snapped Benn’s head violently but he was

undeterred from firing back. Benn’s chin stood firm despite Eubank’s vaunted power and

size advantage.

“I didn’t know he had that in him,” Eubank said.

Benn opened strong in the eighth round with furious blows. And though he connected

he was unable to seriously hurt Eubank. And despite being drained by the weight loss,

the middleweight fighter remained strong all 12 rounds.

There were surprises from both fighters.

Benn was effective targeting the body. Perhaps if he had worked the body earlier he

would have found a better result.

With only two rounds remaining Eubank snapped off a right uppercut again and followed

up with body shots. In the final stanza Eubank pressed forward and exchanged with the

smaller Benn until the final bell. He simply out-landed the fighter and impressed all three

judges who scored it 116-112 for Eubank.

Eubank admitted he expected a knockout win but was satisfied with the victory.

“I under-estimated him,” Eubank said.

Benn was upset by the loss but recognized the reasons.

“He worked harder toward the end,” said Benn.

McKenna Wins

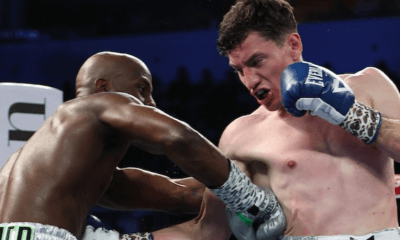

In his first test in the elite level Aaron McKenna (20-0, 10 KOs) showed his ability to fight

inside or out in soundly defeating former world champion Liam Smith (33-5-1, 20 KOs)

by unanimous decision to win a regional WBA middleweight title.

Smith has made a career out of upsetting young upstarts but discovered the Irish fighter

more than capable of mixing it up with the veteran. It was a rough fight throughout the

12 rounds but McKenna showed off his abilities to fight as a southpaw or right-hander

with nary a hiccup.

McKenna had trained in Southern California early in his career and since that time he’s

accrued a variety of ways to fight. He was smooth and relentless in using his longer

arms and agility against Smith on the outside or in close.

In the 12 th round, McKenna landed a perfectly timed left hook to the ribs and down went

Smith. The former champion got up and attempted to knock out the tall

Irish fighter but could not.

All three judges scored in favor of McKenna 119-108, 117-109, 118-108.

Other Bouts

Anthony Yarde (27-3) defeated Lyndon Arthur (24-3) by unanimous decision after 12 rounds. in a light heavyweight match. It was the third time they met. Yarde won the last two fights.

Chris Billam-Smith (21-2) defeated Brandon Glanton (20-3) by decision. It was his first

fight since losing the WBO cruiserweight world title to Gilberto Ramirez last November.

Viddal Riley (13-0) out-worked Cheavon Clarke (10-2) in a 12-round back-and-forth-contest to win a unanimous decision.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

Next generation rivals Conor Benn and Chris Eubank Jr. carry on the family legacy of feudal warring in the prize ring on Saturday.

This is huge in British boxing.

Eubank (34-3, 25 KOs) holds the fringe IBO middleweight title but won’t be defending it against the smaller welterweight Benn (23-0, 14 KOs) on Saturday, April 26, at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium in London. DAZN will stream the Matchroom Boxing card.

This is about family pride.

The parents of Eubank and Benn actually began the feud in the 1990s.

Papa Nigel Benn fought Papa Chris Eubank twice. Losing as a middleweight in November 1990 at Birmingham, England, then fighting to a draw as a super middleweight in October 1993 in Manchester. Both were world title fights.

Eubank was undefeated and won the WBO middleweight world title in 1990 against Nigel Benn by knockout. He defended it three times before moving up and winning the vacant WBO super middleweight title in September 1991. He defended the super middleweight title 14 times before suffering his first pro defeat in March 1995 against Steve Collins.

Benn won the WBO middleweight title in April 1990 against Doug DeWitt and defended it once before losing to Eubank in November 1990. He moved up in weight and took the WBC super middleweight title from Mauro Galvano in Italy by technical knockout in October 1992. He defended the title nine times until losing in March 1996. His last fight was in November 1996, a loss to Steve Collins.

Animosity between the two families continues this weekend in the boxing ring.

Conor Benn, the son of Nigel, has fought mostly as a welterweight but lately has participated in the super welterweight division. He is several inches shorter in height than Eubank but has power and speed. Kind of a British version of Gervonta “Tank” Davis.

“It’s always personal, every opponent I fight is personal. People want to say it’s strictly business, but it’s never business. If someone is trying to put their hands on me, trying to render me unconscious, it’s never business,” said Benn.

This fight was scheduled twice before and cut short twice due to failed PED tests by Benn. The weight limit agreed upon is 160 pounds.

Eubank, a natural middleweight, has exchanged taunts with Benn for years. He recently avenged a loss to Liam Smith with a knockout victory in September 2023.

“This fight isn’t about size or weight. It’s about skill. It’s about dedication. It’s about expertise and all those areas in which I excel in,” said Eubank. “I have many, many more years of experience over Conor Benn, and that will be the deciding factor of the night.”

Because this fight was postponed twice, the animosity between the two feuding fighters has increased the attention of their fans. Both fighters are anxious to flatten each other.

“He’s another opponent in my way trying to crush my dreams. trying to take food off my plate and trying to render me unconscious. That’s how I look at him,” said Benn.

Eubank smiles.

“Whether it’s boxing, whether it’s a gun fight. Defense, offense, foot movement, speed, power. I am the superior boxer in each of those departments and so many more – which is why I’m so confident,” he said.

Supporting Bout

Former world champion Liam Smith (33-4-1, 20 KOs) tangles with Ireland’s Aaron McKenna (19-0, 10 KOs) in a middleweight fight set for 12 rounds on the Benn-Eubank undercard in London.

“Beefy” Smith has long been known as one of the fighting Smith brothers and recently lost to Eubank a year and a half ago. It was only the second time in 38 bouts he had been stopped. Saul “Canelo” Alvarez did it several years ago.

McKenna is a familiar name in Southern California. The Irish fighter fought numerous times on Golden Boy Promotion cards between 2017 and 2019 before returning to the United Kingdom and his assault on continuing the middleweight division. This is a big step for the tall Irish fighter.

It’s youth versus experience.

“I’ve been calling for big fights like this for the last two or three years, and it’s a fight I’m really excited for. I plan to make the most of it and make a statement win on Saturday night,” said McKenna, one of two fighting brothers.

Monster in L.A.

Japan’s super star Naoya “Monster” Inoue arrived in Los Angeles for last day workouts before his Las Vegas showdown against Ramon Cardenas on Sunday May 4, at T-Mobile Arena. ESPN will televise and stream the Top Rank card.

It’s been four years since the super bantamweight world champion performed in the US and during that time Naoya (29-0, 26 KOs) gathered world titles in different weight divisions. The Japanese slugger has also gained fame as perhaps the best fighter on the planet. Cardenas is 26-1 with 14 KOs.

Pomona Fights

Super featherweights Mathias Radcliffe (9-0-1) and Ezequiel Flores (6-4) lead a boxing card called “DMG Night of Champions” on Saturday April 26, at the historic Fox Theater in downtown Pomona, Calif.

Michaela Bracamontes (11-2-1) and Jesus Torres Beltran (8-4-1) will be fighting for a regional WBC super featherweight title. More than eight bouts are scheduled.

Doors open at 6 p.m. For ticket information go to: www.tix.com/dmgnightofchampions

Fights to Watch

Sat. DAZN 9 a.m. Conor Benn (23-0) vs Chris Eubank Jr. (34-3); Liam Smith (33-4-1) vs Aaron McKenna (19-0).

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Floyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

Floyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

In any endeavor, the defining feature of a phenom is his youth. Philadelphia Phillies outfielder Bryce Harper was a phenom. He was on the radar screen of baseball’s most powerful player agents when he was 14 years old.

Curmel Moton, who turns 19 in June, is a phenom. Of all the young boxing stars out there, wrote James Slater in July of last year, “Curmel Moton is the one to get most excited about.”

Moton was born in Salt Lake City, Utah. His father Curtis Moton, a barber by trade, was a big boxing fan and specifically a big fan of Floyd Mayweather Jr. When Curmel was six, Curtis packed up his wife (Curmel’s stepmom) and his son and moved to Las Vegas. Curtis wanted his son to get involved in boxing and there was no better place to develop one’s latent talents than in Las Vegas where many of the sport’s top practitioners came to train.

Many father-son relationships have been ruined, or at least frayed, by a father’s unrealistic expectations for his son, but when it came to boxing, the boy was a natural and he felt right at home in the gym.

The gym the Motons patronized was the Mayweather Boxing Club. Curtis took his son there in hopes of catching the eye of the proprietor. “Floyd would occasionally drop by the gym and I was there so often that he came to recognize me,” says Curmel. What he fails to add is that the trainers there had Floyd’s ear. “This kid is special,” they told him.

It costs a great deal of money for a kid to travel around the country competing in a slew of amateur boxing tournaments. Only a few have the luxury of a sponsor. For the vast majority, fund raisers such as car washes keep the wheels greased.

Floyd Mayweather stepped in with the financial backing needed for the Motons to canvas the country in tournaments. As an amateur, Curmel was — take your pick — 156-7 or 144-6 or 61-3 (the latter figure from boxrec). Regardless, at virtually every tournament at which he appeared, Curmel Moton was the cock of the walk.

Before the pandemic, Floyd Mayweather Jr had a stable of boxers he promoted under the banner of “The Money Team.” In talking about his boxers, Floyd was understated with one glaring exception – Gervonta “Tank” Davis, now one of boxing’s top earners.

When Floyd took to praising Curmel Moton with the same effusive language, folks stood up and took notice.

Curmel made his pro debut on Sept. 30, 2023, at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas on the undercard of the super middleweight title fight between Canelo Alvarez and Jermell Charlo. After stopping his opponent in the opening round, he addressed a flock of reporters in the media room with Floyd standing at his side. “I felt ready,” he said, “I knew I had Floyd behind me. He believes in me. I had the utmost confidence going into the fight. And I went in there and did what I do.”

Floyd ventured the opinion that Curmel was already a better fighter than Leigh Wood, the reigning WBA world featherweight champion who would successfully defend his belt the following week.

Moton’s boxing style has been described as a blend of Floyd Mayweather and Tank Davis. “I grew up watching Floyd, so it’s natural I have some similarities to him,” says Curmel who sparred with Tank in late November of 2021 as Davis was preparing for his match with Isaac “Pitbull” Cruz. Curmell says he did okay. He was then 15 years old and still in school; he dropped out as soon as he reached the age of 16.

Curmel is now 7-0 with six KOs, four coming in the opening round. He pitched an 8-round shutout the only time he was taken the distance. It’s not yet official, but he returns to the ring on May 31 at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas where Caleb Plant and Jermall Charlo are co-featured in matches conceived as tune-ups for a fall showdown. The fight card will reportedly be free for Amazon Prime Video subscribers.

Curmel’s presumptive opponent is Renny Viamonte, a 28-year-old Las Vegas-based Cuban with a 4-1-1 (2) record. It will be Curmel’s first professional fight with Kofi Jantuah the chief voice in his corner. A two-time world title challenger who began his career in his native Ghana, the 50-year-old Jantuah has worked almost exclusively with amateurs, a recent exception being Mikaela Mayer.

It would seem that the phenom needs a tougher opponent than Viamonte at this stage of his career. However, the match is intriguing in one regard. Viamonte is lanky. Listed at 5-foot-11, he will have a seven-inch height advantage.

Keeping his weight down has already been problematic for Moton. He tipped the scales at 128 ½ for his most recent fight. His May 31 bout, he says, will be contested at 135 and down the road it’s reasonable to think he will blossom into a welterweight. And with each bump up in weight, his short stature will theoretically be more of a handicap.

For fun, we asked Moton to name the top fighter on his pound-for-pound list. “[Oleksandr] Usyk is number one right now,” he said without hesitation,” great footwork, but guys like Canelo, Crawford, Inoue, and Bivol are right there.”

It’s notable that there isn’t a young gun on that list. Usyk is 38, a year older than Crawford; Inoue is the pup at age 32.

Moton anticipates that his name will appear on pound-for-pound lists within the next two or three years. True, history is replete with examples of phenoms who flamed out early, but we wouldn’t bet against it.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRingside at the Fontainebleau where Mikaela Mayer Won her Rematch with Sandy Ryan

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoWilliam Zepeda Edges Past Tevin Farmer in Cancun; Improves to 34-0

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoHistory has Shortchanged Freddie Dawson, One of the Best Boxers of his Era

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 320: Women’s Boxing Hall of Fame, Heavyweights and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from Las Vegas where Richard Torrez Jr Mauled Guido Vianello

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFilip Hrgovic Defeats Joe Joyce in Manchester

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoWeekend Recap and More with the Accent of Heavyweights

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Hall of Fame Boxing Trainer Kenny Adams