Featured Articles

THE TECHNICAL BREAKDOWN: Sugar Ray Robinson

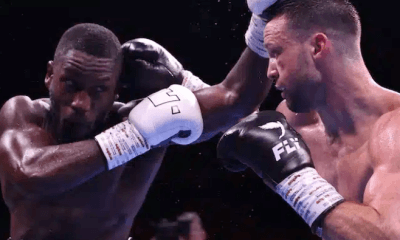

Robinson wasn't above the odd kidney shot or “errant” launch, as he tossed against LaMotta, here. Of course, his mastery of kosher techniques, along with God-given attributes, are what make him arguably the top pound for pounder for the ages.

Robinson wasn't above the odd kidney shot or “errant” launch, as he tossed against LaMotta, here. Of course, his mastery of kosher techniques, along with God-given attributes, are what make him arguably the top pound for pounder for the ages.

The general feeling among the boxing fraternity is that nobody's ever quite ascended to the same plateau of greatness, or was as virtuosic along the way, as Sugar Ray Robinson. There haven't been but a handful of athletes in any sport, whether it be in football, baseball, you name it, whose ability was deemed so extraordinarily good that comparisons to his/her peers seems like a pointless exercise; the man born Walker Smith Jr., the consensus greatest pound for pound boxer to have ever lived, is considered to have been one of those rare exceptions.

And yet, despite much having been written chronicling his life and times, I've found there to be a distinct lack of detail and, I believe, truth when it comes to describing the techniques that Robinson employed between the ropes.

“He could end a fight any time he chose to, with either hand!”

“He was perfection personified, utterly flawless”.

“Defensively, he was masterly”.

In terms of technical analysis on Sugar Ray Robinson, the above is about as in-depth as I've seen on him.

Needless to say, because Sugar Ray Robinson has attained almost God-like status as a fighter over the years, certain realities regarding his in ring tendencies seem to have been replaced by mythology; tap the name Sugar Ray Robinson into your search engine and watch the folklore regarding his style and technique unfold. There's no debating that Ray Robinson wasn't an exceptional fighter. He most certainly was. Any all-time pound for pound list that has Robinson's name outside of the top three, quite frankly, shouldn't be taken very seriously. Worst case scenario? Sugar Ray Robinson is, with his 175-19-6 {109} record, at the very least, the third greatest fighter who ever lived. What is open for debate, however, is the misconception that when it comes to how he actually operated in the ring as a fighter, Sugar Ray Robinson's genius is often attributed to his God-given talent, which, clearly wasn’t the case. I believe it does Ray Robinson a major disservice to put his success in the ring down to nothing else but things he was born into.

And so, rather than simply regurgitate what's already out there regarding Ray Robinson's life story and accomplishments, I'd like for this to be thought of as a kind of case study detailing what it was exactly that made him so formidable as a fighter. Robinson's accolades have been well documented elsewhere so basically, you're not going to find much else apart from Sugar Ray Robinson's fighting style and techniques mentioned here.

For the purpose of this article then, I’ve broken Robinson's attributes down into two categories: physical and technical. Both Robinson's physical and technical attributes aided one another perfectly, but I feel that it's important to mention them both separately, so that the reader has a clear understanding of just how important each were to Ray's dominance in the ring.

Physical

Height and reach:

One of the biggest misconceptions about Robinson is that he spent most of his career facing “larger” men. As I'm sure most of you reading this will be aware, Ray Robinson, who began his professional career as a lightweight before fighting mostly as a welterweight, eventually went on to compete at middleweight and even once at light heavyweight. I feel the area that is taken for granted the most when discussing Robinson's dominance in the ring as a welterweight is the size advantage he must have enjoyed over almost all of his opponents. At 5'11″ and with a 73″ reach –big for a welterweight, even by today’s standards- Ray Robinson must have possessed a size advantage over many of his lightweight and welterweight opponents not unlike that of Thomas Hearns. What's interesting when you see Ray on film is that he's nearly always the bigger man in the ring even though most of the footage that exists is of him fighting as a middleweight against perceived larger men.

Take a look at the size of Ray next to Bobo Olson, Rocky Graziano, Jake Lamotta, Randy Turpin and Gene Fullmer -all middleweights, all of them shorter than Ray. Even when Robinson fought for the light heavyweight crown against Joey Maxim, who at 6'1″ and with a 71″ reach, pretty much shared the same physical dimensions with Robinson. It's safe to say that even without any of his other attributes –of which I'll get to in a moment- Robinson's advantages in size and length would have always been tough to overcome for many of his welterweight opponents.

As I've already stated, the footage we have of Ray is mostly of him fighting as a middleweight, so one can only imagine how he would have matched up physically against other welterweights of his time. For a modern visual, I think the physical advantages that Robinson had over his opponents as a welterweight would have been similar to those owned by Nonito Donaire over his flyweight opponents; some of Donaire's victories over stellar opposition at flyweight rank among the most one sided and nonchalant that I've ever seen in a boxing ring. Donaire’s opponents have been rather negative lately, but you have to concede that he isn't nearly as dominant these days now he's facing men of a similar size.

Remember, apart from his one fight with Jake Lamotta, in which the Bronx Bull held a 16 pound weight advantage, Ray Robinson was undefeated before moving up to middleweight. His record at that time stood at 110-1-2. The two draws on Robinson’s record to Jose Basora and Henry Brimm were also against middleweights. Incidentally, Robinson knocked out Brimm inside the opening minute of the opening round in the rematch and he had also previously won a decision over Basora.

Size alone is a difficult obstacle to overcome in a boxing ring. Unless an opponent is quick enough and knows how to get inside on a taller opponent, then size will usually come out on top. I'd argue with anyone that it is in fact the Klitsckho brother’s advantages in size, not skill and technique that make them nigh on impossible to handle for their generally smaller heavyweight opponents. I believe that because Robinson was always so much bigger than most of his welter/middleweight opponents, some of his success, especially as a welterweight, can be attributed to his sheer size.

Strength:

If you take a look at Robinson's fight with Joey Maxim, you'll see him easily controlling the bigger man during the clinches. Even though Maxim had a 17 pound weight advantage over Robinson, he could never get the better of him on the inside once the distance was closed. During the fight, Robinson showed his strength by tying up Maxim's arms and in controlling his biceps. Eventually, the 104 degree heat got the better of Robinson on that day, but not before he showed that he could not only out-slick, but out-muscle a natural light heavyweight. Now, if you consider how Robinson was able to manoeuvre someone weighing 173 pounds around, it's no wonder he was able to do the same with many of his welterweight and middleweight opponents. At some time or another during their numerous fights, Robinson always managed to control the likes of Maxim, Fullmer, Basilio, Lamotta and Olson on the inside. Remember, Ray's objective in there was to separate himself from his opponent so that he could get off his rapid fire combinations. Inside fighting may not have been his forte, but similarly to Muhammad Ali, he clearly knew how to tie up and control a fighter at close quarters should they be successful in breeching his optimum fighting distance.

Speed:

Despite what legend will have you believe, Ray Robinson wasn't the owner of the quickest pair of hands ever. Going one step further, I'd state with confidence that from what I've seen on film, Ray Leonard, Meldrick Taylor, Terry Norris, Hector Camacho, Thomas Hearns, Roy Jones Jr., Floyd Mayweather Jr.and Manny Pacquiao all had/have faster hands. In fact, it's possible that even far bigger men like Muhammad Ali, Floyd Patterson and Mike Tyson may have had faster hands. However, if we're narrowing it down, between the period of 1940-1965, which was Robinson's entire professional career, then there weren't many fighters who competed around at that time period or who fought in or around the same weight division, with the exception of Kid Gavilan and Charley Burley, who could compare to Ray in the hand speed department. Which means, of course, Ray would have always held an advantage in hand speed over almost every opponent he ever faced.

Something else that must be accounted for when watching Ray in full flow is that he always tried to hurt his opponents with nearly every punch he threw. If you compare a combination thrown by Meldrick Taylor with one thrown by Ray Robinson, you'll see apples and oranges in terms of where their intentions lay. Yes, Meldrick's combinations were undoubtedly faster, but Ray's were more explosive with more emphasis placed on hurting a man as opposed to impressing some judge. When watching Ray, I feel he jeopardized some of his speed in favour of more spite and precision. One of the biggest differences between fighters these days and those of yesteryear is that winning a decision seemed to be the last thing on a fighter's mind back then. Nowadays, fighters seem all too happy to take turns in firing away blindly at arms and gloves, racking up points as they go. Back when Ray Robinson plied his trade, creating and exploiting openings was first and foremost on a fighter's agenda. Back then, fighters were far more focused on ending a fight within the distance.

It wasn't only Robinson's hands that were notably faster than many of his opponents. He also enjoyed a significant advantage in foot speed over most of them too. Most of the time, Ray fought off his back foot, behind the jab where his foot speed allowed him to maintain his preferred fighting distance. Again, there are fighters on film who appear to be quicker than Ray was in moving around the ring. In my view, Ray Leonard, Hector Camacho, Orlando Canizales, Roy Jones Jr. and Manny Pacquiao were all quicker than Robinson in getting to their positions. However, Robinson was a lot bigger than any of these men in correlation with his often smaller opposition. It's very unusual for a fighter to be so much taller and longer than his opponent while also having faster hands and feet than them as well. Thinking of fighters who've been so much bigger and so much faster than their opponents, only Muhammad Ali and a flyweight Nonito Donaire come to mind. The fact that Ray Robinson held advantages over his opponents in not only size, but in hand and foot speed too, goes a long way towards showing why he was so formidable as a welterweight and even as a middleweight.

Power:

For my money, Robinson's power has been slightly blown out of proportion over time. By that, I mean I'm pretty sure he wasn't capable of ending a fight anytime he chose to like most accounts would have you believe. Yes, Ray Robinson was a powerful puncher, but I don't think he packed the natural wallop that men like Julian Jackson or Thomas Hearns did, who often knocked men unconscious with even glancing blows. Robinson's knockouts came on the back of excellent technique and timing, as opposed to brute force.

No, Ray wasn't like George Foreman, who was a murderous puncher even though his punches seemed to lack true technique. Robinson's technique, particularly in his short hooks and uppercuts, was every bit as good as Joe Louis's from what I've seen of both men. Don't get me wrong here, I'm not suggesting that Robinson couldn't punch, because he clearly could. All I'm saying is that I believe Robinson's knockouts came about more from speed, precision, timing and technique as opposed to “his dynamite fists”. Ray was more like Archie Moore -the leading knockout artist in boxing history- who wasn't a huge puncher either as he relied more on strategy and skill to find openings and take advantage of his opponent’s mistakes. Conversely, Ernie Shavers is someone who I'd consider to have had a ridiculous amount of power behind his punches but with little in the way of true punching technique. Ray Robinson was most definitely a thoughtful puncher.

Chin:

I'll keep this short and sweet. Ray Robinson, even though he was dropped numerous times throughout his career, was never stopped in more than 200 fights. Yes, his overwhelming offense may have had plenty to do with that, but as he slowed as he got older, Ray became a lot more hittable and his chin had to serve him well. Along with his size and athleticism, Robinson’s punch resistance is probably the only other attribute that wasn’t manufactured and could be considered “God-given”.

Now that we've covered Ray Robinson's physical prowess, I think we can agree that by looking at the film that's available, Robinson's advantages in height and length combined with his tremendous hand and foot speed would’ve been a tough obstacle for any fighter from welterweight to middleweight to overcome. His strength on the inside, on show in the fights against the likes of Jake Lamotta, Joey Maxim and Carmen Basilio, shows that inside fighters wouldn't have been able to have their way with him could they have managed to close the distance and on the outside, with his speed, length and punching accuracy, anyone who lacked above average defense or who utilized good head movement would have found themselves walking onto Robinson's combinations for as long as they were able to stand.

Even without his technical expertise, which I'll be going over in a moment, Sugar Ray Robinson was an excellent fighter based on physicality alone; excellent hand and foot speed, great length, good strength, above average punching power and a world class chin.

Technical

Circling Behind the Jab, Robinson Style:

Ray Robinson's stance was very similar to that of Joe Louis, in that his head was slightly away from the centre line and off to his right, which made him tough to hit with a right hand. However, unlike Joe, who kept his right glove out in front of him in a parrying position to block against the left jab and his left elbow tucked in close so that his jab was coming from chest height, Robinson kept his right glove close to his chin and in position to catch any of his opponent's right or left handed attacks while his left hand, his jabbing hand, was almost down by his waist. You see, whereas Louis preferred to use feints and take small advancing steps in an attempt to lure his opponent into opening up, Robinson was more like Ali in that he preferred to circle counter clockwise behind his jab and into his often orthodox opponent's power hand, which seems counter intuitive, but it worked well for Ray because of his stance, which was designed to avoid getting hit by an orthodox fighter’s power hand. Strategically, there was a resemblance between what Robinson and Ali did with the jab. The biggest difference between the two, though, was that Ali seemed to rely exclusively on a jab, jab, right hand combination aimed at the head as he circled left, whereas Ray was very versatile with not only the punches he threw after the jab, but in the execution of the jab itself. If you look at the Jake Lamotta fight, you'll see Ray repeatedly back up while mixing up his jab to the head and body, sometimes with authority, other times as a set up shot, followed by just about every single punch in the book. On that night, against a crouching pressure fighter in Lamotta, Ray's uppercuts thrown from his waist –the same starting point for his jab- were almost indefensible. On other occasions, like against Carmen Basilio, you'll notice Ray back peddling diagonally behind his jab and onto Carmen's trailing hand. Once Carmen opens up in an attempt to land his over hand right, Robinson immediately steps forward and to Carmen’s right and throws his left hook inside of Basilio's wide right hand. Ray Robinson's jab was his bread and butter punch which he used to control his opponents or set up just about every other punch he threw.

If you go on YouTube and click on any one of Ray Robinson's fights, it doesn't matter which, you'll notice him; ~Circling left with his left shoulder slightly raised. ~His head away from the centre line and slightly off to the right. ~His front foot planted with his back foot slightly raised. ~His right glove open and by the left side of his chin. ~His left hand relatively low -this is the signature Ray Robinson stance. No matter how late it got in a fight, Robinson never lost sight of his shape or form and never stopped circling behind his jab. Robinson was very methodical and never strayed away from boxing’s most basic and cultivated punch, which he mastered.

Footwork:

Following on from circling behind the jab, Robinson's footwork was impeccable. The best example of Robinson's sublime movement on film can be found in his fight with Bobby Dykes. Throughout, you'll see Ray move in, slide out and circle his target, all the while staying perfectly balanced and in position to punch. One of the most famous sayings regarding Ray Robinson is “he could throw knockout blows going backwards”. Basically, this statement alludes to Ray's footwork being so good that despite him moving away so quickly, his feet never came together which meant he always remained well balanced, allowing him to generate good power off of his back foot. Ray Robinson's multi-dimensional footwork, despite its aesthetics, was purposeful in that he could hurt an opponent in pursuit or in retreat. It was also his first line of defense, of which I’ll get to shortly.

The Left Hook/combinations:

As you all know, there’s a certain Ray Robinson left hook that is now legendary. But what may surprise you, is that it isn't going to get a mention here. Well, not yet anyway. I think it fits in much better elsewhere in this article.

Robinson's go-to left hook was basically the one he threw in threes and fours. Robinson's ability to double and even triple up on his left hook is what made him so unpredictable on offense. If you look at the Luc Van Dam fight, you'll see Ray circling left while throwing two left hooks to the body followed by a third left hook upstairs. All three shots are thrown in quick succession and the final blow comes from a ridiculous angle, which made it very difficult to detect. Most fighters are trained to expect punches to be thrown in a chain sequence; for example, right, left, right, left. Because Ray doubled and even tripled up on his shots, which was pretty revolutionary for his time, many of his opponents couldn't anticipate what shot was coming next.

My all-time favourite Sugar Ray Robinson moment/knockout illustrates this technique perfectly. In the final sequence of the Rocky Graziano fight, you'll see Sugar Ray Robinson in a nutshell. First, Robinson is typically circling behind the jab, pivoting clockwise off his lead foot. Then, as Graziano attempts to land a straight left, Robinson circles out and away from the ropes. With Graziano's back now up against the ropes, Robinson moves in for the kill. Ray throws a hook and they fall into a clinch. As they break away, Ray lands a short uppercut, followed by two quick left hooks, followed by a right cross which results in Graziano's mouthpiece flying out of the ring along with his senses. When you first look at this knockout, you'll probably think it's all about the jolting right hand that Ray ends the fight with that's the focal point here. But when you look again, closely, you'll soon realize that it's the two left hooks prior to the right hand that are the real fight-ending blows. As Ray catches Rocky twice with the left, you'll see Rocky begin to adjust his guard slightly in anticipation of a third, leaving himself open for a right hand, which Robinson capitalized on. All of this takes place within the blink of an eye and it really is elite level stuff. That’s why it's my favourite knockout from possibly the greatest fighter who ever lived.

In my view, Sugar Ray Robinson is right up there with Joe Louis and Julio Cesar Chavez Sr. as the best combination puncher ever seen on film. The accuracy, variety and unpredictable patterns of Robinson's combinations are what made his punches so hard to defend against for his opponents. Again, looking at the Jake Lamotta fight, you'll see Lamotta in a state of confusion every time Ray moves in to attack. Ray’s combinations thrown at Lamotta over the course of those thirteen rounds were scintillating. He doubled and tripled up on hooks, uppercuts and straights which were always thrown in alternating patterns and in different rhythms. Robinson's punch variety was of the highest order. What also made Robinson’s combinations so effective was that every punch was thrown as a precursor to the next, as the knockout of Rocky Graziano illustrates so vividly.

Ring intelligence:

Now, the reason why Ray Robinson's left hook decapitation of Gene Fullmer wasn’t mentioned when I was describing his go-to left hook is because I believe it was lightning in a bottle. This wasn't the typical Ray Robinson left hook that he doubled up or tripled up on in almost every fight. No, this was something else. What I find more rewarding that the actual knockout blow in the Fullmer fight was the way he set it up. Hence, I've chosen to detail it under “Ring Intelligence” instead of under “The Left Hook”. Firstly, Gene Fullmer was a known puncher with the right hand and he had used it extensively against Robinson in their first fight. Robinson was aware of this so he set about drawing the right hand out in order to counter it. Backing up, Ray stepped in and landed a right hand to Fullmer's body. Robinson then repeated the action -back stepping, before dropping his level and stepping in with a right hand to the body. Because Fullmer thought Ray was going to repeat this a third time, he set himself to throw a right hand as Ray would be stepping in. Aware of Fullmer's intentions, Robinson faked right but instead twisted back across and connected with a picturesque left hook that knocked -the never before or since- Gene Fullmer out. For my liking, as was the case in the Rocky Graziano knockout, the actual knockout blow is only half the story here. The bigger picture is that of Robinson's ability to set a trap. Robinson's uncanny ability to think not one, but three moves ahead is what earned him what has been labelled the greatest knockout of all time.

Defense:

Going against the grain once more, I'd like to detail some of Robinson's better defensive traits by describing his two knockouts of Carl “Bobo” Olson. In both knockouts, which are on film, Olson gets himself into an exchange with Robinson. At first, it's easy to think that Robinson's speed in a shootout is what results in Olson being sprawled across the canvas on both occasions. However, I believe what lands Robinson his knockouts -apart from his accuracy- is his evasiveness while punching. As both men are firing at each other, contrast Robinson's head movement with that of Olson's. On both occasions, Robinson is almost rolling with his own punches as he's letting his hands go. His head never remains stationary as he's punching. Olson, on the other hand, is rooted to the spot. His head remains central and in the line of fire. Even if Robinson's eyes are closed as he's unloading, there's a good chance he's going to connect because Olson's head hasn't moved away from the centre line. Even when Ray Robinson was on the offensive, he always remained defensively responsible.

In terms of defending against his opponents when he wasn't on the offensive, Robinson really shouldn't be considered among the elite. Robinson was tagged often and was sent to the canvas numerous times during his career. Defensive masters like Willie Pep, Pernell Whitaker, Nicolino Locche, Wilfred Benitez, Roberto Duran, James Toney and Floyd Mayweather were/are far more proficient when it comes to making an opponent miss. As his legs began to erode later on in his career, Ray began falling back to the ropes where he would often defend himself by rolling with punches. At his best though, Ray's first line of defense was his footwork, which he used to establish distance between himself and his opponents through lateral and lineal movement. Although he was by far the better technician, Robinson’s elusiveness in the ring was more reminiscent to that of Roy Jones and Muhammad Ali, in that they seldom remained in the pocket, looking to slip and counter. When Robinson wasn’t attacking, he always utilized plenty of footwork to avoid being hit. It must be said though, because Robinson was always looking for the knockout, he was always going to get hit more often as he left more openings -a fighter is at his most vulnerable in the ring as he’s punching. This isn’t a knock on Robinson, but despite what some people may have been told, Ray Robinson was not a defensive savant. According to reports, Robinson struggled with the jab of both Tommy Bell and Kid Gavilan and as the film shows, Robinson also struggled with Randy Turpin’s jab in their first meeting and was hit regularly by Ralph Jones.

Infighting:

Similarly to Muhammad Ali, I don't think infighting was one of Ray Robinson's best assets. Sure, he was more rounded on the inside than Ali, but it was never his intentions to let the fight take place there. Robinson was at his best at mid/long range, keeping his opponent on the end of the jab before allowing them to walk onto power shots, or shortening up the distance allowing him to land his mid-range hooks. Although he preferred to avoid the inside, Ray was more than proficient once an opponent got inside on him. Like Ali, he knew how to control a fighter by clamping down on the back of their neck or by tying them up and controlling their biceps. Ray wasn’t the best as far as inside fighting goes. Fighters like Henry Armstrong, Roberto Duran, Joe Frazier, James Toney and Julio Cesar Chavez Sr were much more formidable at this range, both offensively and defensively. However, because Robinson knew how to prevent a fighter from getting inside on him, and could more than hold his own should anyone manage to smother him, he clearly wasn't the fish out of water that Amir Khan is once an infighter is successful in closing the distance on him.

Right hook to the kidney:

Illegal or not, this was one of Ray Robinson's signature shots. Even though he was once disqualified for using it against German fighter Gerhard Hecht, it was always a punch that featured in many of his fights. In fact, it can be seen in nearly every Ray Robinson fight that was ever captured on film. Firstly, this punch worked for Ray because of its unpredictability. The conventional punch that is usually thrown immediately after a jab is usually another jab or a right cross. What Ray would sometimes do, was shoot his jab high and then immediately drop low where he then threw wide his right hook. Ray threw his right hook to the side/kidney differently from most. As he stepped in and to the left with it, he turned it over more, ensuring his thumb was almost pointed to the floor and his right arm was arced away from his body, so that his weight was transferred on to his front foot. Notice in many of Robinson's fights how once an opponent bent at the waist and presented Ray with their back, he thought nothing of corkscrewing his unorthodox right hand around their sides and into their kidney. Again, this was a signature punch of Robinson that he used in nearly all of his fights.

Conclusion

For me, there was no magic involved. I believe objective reasons are behind Sugar Ray Robinson's genius in the ring. Strip away all of the myths and legends which surround him and you're left with a consummate boxer-puncher, who, during his prime as a welterweight and even during the twilight of his career as a middleweight, was taller than most, faster than most, hit harder than most, and had a better chin than almost anyone ever. He also learned on the job, facing seasoned pros like Fritzie Zivic, Marto Servo and Henry Armstrong very early in his career, before even being considered for a shot at the welterweight title against Tommy Bell -contrast Robinson’s learning curve with Saul Alvarez and Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. Unlike them, Robinson was seasoned by the time he became champion.

No, Ray Robinson wasn't a perfect fighter, no fighter ever will be, but he was an extremely well rounded one. Sure, there’ve been faster, there’ve been harder hitters, there’ve been better counterpunchers and defenders who were tougher to find in the ring than Robinson, but I'm not sure that I've ever seen a fighter who could combine everything -offense/defense, speed, power, timing, rhythm, coordination- and put it all together the way Robinson did.

Even as an aging middleweight, Ray Robinson’s brilliance was obvious and he remains one of the very best fighters ever captured on film, he was past his prime. By using the footage that exists and trying to extrapolate from it, I think it’s safe to assume that Sugar Ray Robinson at welterweight must have been about as good as it gets.

Writer's Note: Thanks for taking the time to read such a long piece, readers. All the fights that have been mentioned in this article are available on YouTube and are of Ray Robinson fighting as middleweight only. Sadly, there's no clear footage of Ray Robinson performing during in his prime. The closest we've got to it is grainy footage of his fights with Tony Riccio, Charley Fusari, Sammy Agnott, Cliff Beckett and Bernard Docusen, which are also available on YouTube. Unfortunately, the quality of those fights is really poor.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoEkow Essuman Upsets Josh Taylor and Moses Itauma Blasts Out Mike Balogun in Glasgow

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNewspaperman/Playwright/Author Bobby Cassidy Jr Commemorates His Fighting Father

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 326: A Hectic Boxing Week in L.A.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoHiruta, Bohachuk, and Trinidad Win at the Commerce Casino

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDavid Allen Bursts Johnny Fisher’s Bubble at the Copper Box

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoItaly Mourns the Death of Legendary Boxer Nino Benvenuti