Featured Articles

Vinny Paz is Going into the Boxing Hall of Fame; Hey, Why Not Roger Mayweather?

Vinny Paz, formerly Vinny Pazienza, will be formally inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame under his adopted name on Sunday, June 8.

It’s a controversial pick. There’s a strong sentiment that Paz was permitted to jump the queue, so to speak, taking his place in line ahead of more worthy contemporaries who remain on the outside looking in. Philadelphia boxing trainer Stephen “Breadman” Edwards, a keen student of boxing history with an emphasis on the 1980s, submits that Meldrick Taylor, Chris Eubank Sr, Simon Brown, Nigel Benn, and Marlon Starling have stronger IBHOF credentials. Trainer Otis Pimpleton, a fixture at the Mayweather Boxing Club in Las Vegas since it opened in 2007, has been beating the drums for Roger Mayweather.

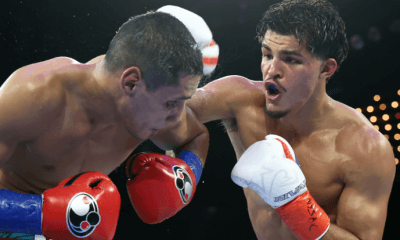

Vinny Paz

The “Pazmanian Devil,” the Pride of Rhode Island, was active from 1983 to 2004, finishing with a record of 50-10 (35 KOs) while answering the bell for 460 rounds. He won world titles at lightweight and at super welterweight and a passel of fringe titles at super middleweight.

Early in his career, Pazienza won two of three from Greg Haugen in a trilogy that consumed 40 rounds. Late in his career, he twice defeated the great Roberto Duran although it’s worth noting that Duran was then 43 years old. His best win, in hindsight, was his 10th-round stoppage of Lloyd Honeyghan. They met in Atlantic City on June 26, 1993, in a match contested at the catch-weight of 158 pounds.

True, Honeyghan, the former lineal welterweight champion – the first man to defeat Donald Curry – was getting a little long in the tooth and moving up in weight, but it didn’t figure that the fight would be the rout that it became. Vinny dominated from the opening bell until Honeyghan’s corner tossed in the towel in the 10th frame.

What made Pazienza’s showing more remarkable is that it came not quite 20 months after he suffered a broken neck in a horrific car accident that almost left him a quadriplegic. That he was able to resume his career and score several notable wins after his near-death experience became grist for a Hollywood filmmaker, begetting “Bleed for This,” a well-received, big screen biopic.

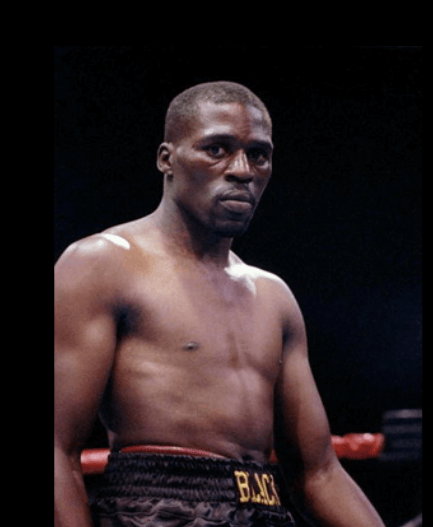

Roger Mayweather

Boxing’s original Black Mamba and the second-most prominent member of a famous fighting family, Roger Mayweather had a near-identical record to Pazienza (Roger finished 59-13 with 35 KOs) and, like Pazienza, won world titles in two weight classes. During the late 1980s, he was a big draw in Los Angeles at venues like the Olympic Auditorium and the LA Sports Arena where the locals turned out to see him lose to a Mexican opponent which he almost never did, earning him the sobriquet The Mexican (sic) Assassin and leaving it to Julio Cesar Chavez to restore the lost luster of his compadres.

Unlike the five boxers on Breadman Edwards list, Mayweather shared the ring with Vinny Pazienza. They fought on Nov. 7, 1988, at Caesars Palace in the overture to Sugar Ray Leonard’s match with Donny LaLonde.

Vinny taunted Roger throughout the 12-round fight, but all the while he was taking a beating. Mayweather wobbled him several times, knocked him down in the 11th, and won by margins of 7, 7, and 10 points. (Mayweather’s final punch was a right uppercut that left a bruise on the face of Pazienza’s hot-tempered trainer Lou Duva who barged into the ring and charged at Roger with his fist clenched after the two fighters exchanged punches after the final bell.)

Otis Pimpleton was seven years old when he first met Roger Mayweather. Their families lived around the block from each other in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Roger, six years older, was like a big brother to Otis. They worked out after school at the United Youth Boxing Club where the teenage Roger was such a gym rat that the managers of the facility gave him the keys to the gym.

When Otis moved to Las Vegas to pursue a pro career, Mayweather was waiting for him. “Roger made me spar with Horace Shufford [an established pro] as soon as I got off the plane,” recollects Pimpleton. “He didn’t tell me who I was fighting. That was Roger. Back home in Grand Rapids, he was always making matches in the gym.”

When Pimpleton thinks of Roger Mayweather in Hall of Fame terms, he thinks of Roger more as a trainer than a boxer. “He never got enough credit for what Floyd accomplished,” he says.

That’s an interesting point. The view from here is that if a boxer on the Hall of Fame bubble stays relevant in the sport after he retires, that ought to eventually push him over the hump.

James “Buddy” McGirt, who had his last fight in 1997, was named to the Hall with the class of 2019. Was McGirt a worthy honoree? Yes, but in my mind what clinched it is that he transitioned into a prominent trainer.

There’s a school of thought that Floyd Mayweather Jr was so good and so dedicated to his craft that he basically trained himself. There’s a kernel of truth in that, but Roger was there from the very beginning of his nephew’s pro career when Floyd’s father was in prison and Roger would be the chief voice in the corner for the vast majority of Floyd’s career including his megafight with Manny Pacquiao.

Roger honed the skills of several other prominent boxers, if only in a secondary role, but preferred working with kids. “I teach kids as young as 8 years old,” he told this reporter in an interview conducted three decades ago. “That’s where the real satisfaction comes in, seeing someone develop from scratch.”

Otis Pimpleton, mentored by Roger, carries on his legacy. He trains Andrew Tabiti, a former world title challenger at cruiserweight who returns to the ring on June 13 in Ghana on a show that will air on DAZN, but he doesn’t ignore the kids who show up at the gym after school lets out. And Roger’s influence goes beyond the mere physical. “When you did well, Roger would never give you the credit, but he would never speak bad about you to anyone; he always had your back,” says Pimpleton, who adds that Roger was no fool with his money. “Everybody thought Roger was broke, but that wasn’t so,” he says, while noting that Floyd Jr. stepped up and made certain that Uncle Roger had 24/7 care after Roger became lost in the fog of dementia. (Mayweather passed away in 2020 at age fifty-nine.)

In defense of Vinny Paz, he was one of the most exciting fighters of his era. Matt Andrzejewski believes that his induction was long overdue. “(Vinny) was must-watch TV,” wrote Andrzejewski in a story that appeared in these pages in 2018. “People watched – and not just those hooked on boxing; Paz had crossover appeal.”

In professional boxing, a young fighter’s perceived marketability carries more weight than his talent in the eyes of promoters. One could argue that a Hall of Fame for retired boxers should be free of this bias, but there’s more to the story and that’s a story best left for another day.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision