Featured Articles

Catching Up with Wayne McCullough Thirty Years After His Historic Win in Japan

We are approaching the 30th anniversary of one of the proudest moments in Irish boxing history. On July 30, 1995, Wayne McCullough wrested the WBC world bantamweight title from Yusuei Yakushiji in Nagoya, Japan.

The heavily favored Yakushiji, fighting in his hometown, was making his fifth title defense. The decision was split, but if the nod had gone to the local fighter, it would have been a grave injustice. The Pocket Rocket (the nickname McCullough carried over from his amateur days) won by 8 points on one of the scorecards.

There would be no rematch. Yakushiji retired and embarked on a successful career as an actor.

A two-time Olympian, McCullough was already a star in the Emerald Isle where amateur boxing is big. At the 1988 Summer Games in Seoul, the mighty-mite from Belfast’s troubled Shankill Road district was picked to be the flag bearer for the Irish Olympic delegation although at age 18 he was the youngest member of the team. Four years later in Barcelona, he won a silver medal, losing to Cuba’s Joel Casamayor in the finals. Between those two Olympiads, McCullough won gold in the flyweight division at the Commonwealth Games in New Zealand.

McCullough was a hot commodity coming out of the Barcelona Games. The best guess is that he would sign with Belfast’s Barney Eastwood who had guided the career of Wayne’s hero Barry McGuigan until McGuigan and Eastwood had a bad falling out, but he cast his lot with an upstart, wealthy Denver businessman Mat Tinley who founded a company called America Presents and steered him to Las Vegas-based trainer Eddie Futch. (In an interview with The Guardian, Tinley said he was sold on Wayne’s potential after having pizza and beers with a couple of Belfast guys, one of whom, Paul Hewson — better known as Bono from the rock group U2 — was a big McCullough supporter.)

Wayne was reluctant to leave Northern Ireland, but jumped at the chance to be coached by Futch, the fabled trainer whose former fighters included Joe Frazier and Ken Norton, the only men to defeat Muhammad Ali through the first 57 bouts of Ali’s career.

Futch was then 81 years old and contemplating retirement. Watching tape of McCullough convinced him to hang around a bit longer, but what sealed the deal was the Irishman’s demeanor. Futch had no tolerance for loudmouths. “[I’d heard about] this rough, tough little kid from Belfast,” he said. “I met him and he was a nice, soft-spoken little fella. I thought to myself, ‘I heard he was rough. Where is it?”

—

McCullough took Cheryl Rennie, his 19-year-old fiancée, soon to be his wife, with him when he moved to Nevada. He acknowledges that without her he likely wouldn’t have stayed in Las Vegas very long.

In Belfast, he lived in a government-subsidized home with six siblings who shared one bathroom in the gritty Shankhill Road neighborhood, an area scarred by sectarian violence. “I saw things that would make your toes curl,” he says. “In Las Vegas, Cheryl and I were set up in a luxury apartment complex with a pool, but yet I was homesick. Sundays were the worst because the gyms were closed.”

Little by little, Las Vegas grew on him. He and Cheryl and their daughter Wynona, a professional singer and songwriter (she competed in the Irish version of American Idol), currently reside in the southwest edge of the city in a 3,000-square foot home with a four-car garage converted into a boxing gym. More about that later.

—

Eddie Futch prioritized defense, but didn’t tamper with McCullough’s fan-friendly, in-your face style. To prepare for Yakushiji, Futch removed McCullough from the hustle and bustle of Las Vegas, establishing a camp in bucolic St. George, Utah, and then a camp in Honolulu before the three of them – Wayne and Futch and Futch’s chief assistant Thell Torrence – continued on to Nagoya.

McCullough defended his title twice, stopping Denmark’s Johnny Bredahl in eight before a raucous home crowd in Belfast and then edging Jose Luis Bueno in Dublin. The Mexican was a hard nut to crack, leaving McCullough with a busted eardrum that knocked him out of a fight with European bantamweight champion Luigi Camputaro. It would have been the co-feature underneath De La Hoya-Chavez I in the big outdoor arena at Caesars Palace and one of Wayne’s regrets as he looks back on his career is that he never got to perform at that storied venue.

McCullough was outgrowing the bantamweight division. After a tune-up in Denver, he challenged WBC 122-pound kingpin Daniel Zaragoza. A three-time title-holder in two weight classes, the grizzled veteran from Mexico City would saddle the Pocket Rocket with his first defeat.

McCullough came on strong and thought he did enough to win it. Eddie Futch thought so too, as did the referee, Joe Cortez, but in the eyes of two of the judges (and most ringside observers) it was too little, too late.

The big gun in the next weight class up was Naseem Hamed. When McCullough fought him, the southpaw from Sheffield was 30-0 and riding a 19-fight knockout streak, the last 11 in world title fights. To casual fans, the flamboyant featherweight may have been best known for his elaborate ring entrances concluding with a backflip onto the canvas. “It is not unusual for the entrance to take longer than the fight,” wrote Mark Kriegel in the New York Daily News.

There was bad blood between them. Two years earlier, Hamed had defended his title against Manuel Medina in Dublin. McCullough, back in Ireland for a short holiday, crashed the weigh-in and he and Hamed exchanged insults. During the Hamed-Medina fight, the crowd chanted McCullough’s name with the Pocket Rocket egging them on from his ringside seat.

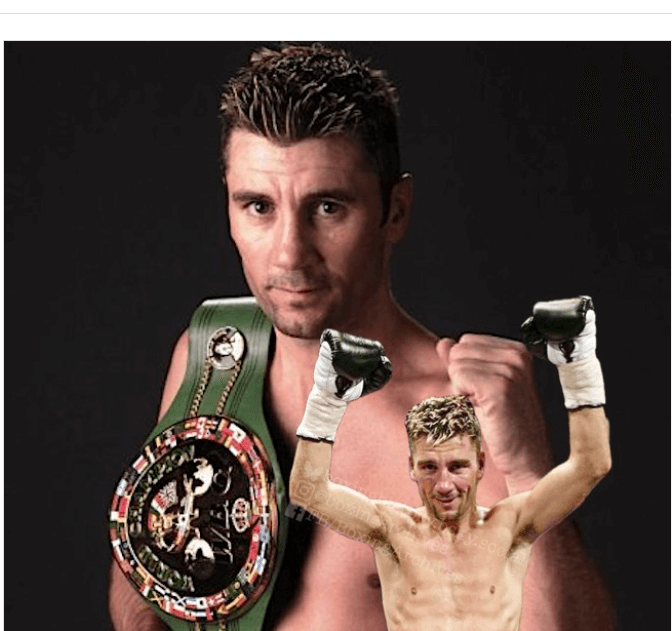

British boxing writers said that McCullough vs. Hamed could fill a soccer stadium, but the bout landed in Atlantic City where it played out in an unexpected fashion. McCullough, who was walked into the ring by the famous dancer and choreographer Michael Flatley, the “Nureyev of Irish folk dancing,” chased Hamed around the ring for 12 rounds but lost a unanimous decision that was greeted with a chorus of boos.

Wayne and his friend Michael Flatley

This was McCullough’s first pro fight without Eddie Futch in his corner. The venerated trainer, then 84 years old, had retired to spend more time with his devoted wife Eva, a 38-year-old Swedish masseuse.

McCullough’s post-Futch career was spotty. He won only five of his final 10 fights, the first setback coming in a failed bid to win the WBC 122-pound world title held by the brilliant Erik Morales (a fight pushed back five months when McCullough suffered a back injury in training) and the last when he returned to boxing after a 3 ½-year hiatus for a bout in the Cayman Islands where ring rust and assorted injuries left him a shadow of his former self. (Before his final fight, he had a match in Belfast with European super bantamweight champion Kiko Martinez that was cancelled when Martinez came in overweight at the weigh-in.)

Wayne’s last two fights before his ill-advised Cayman Island swan song were with WBC 122-pound kingpin Oscar Larios, then recognized as the best fighter to come out of Guadalajara (a distinction he would yield to Canelo Alvarez).

Their first meeting, staged at an Indian Casino in California’s San Joaquin Valley, was a tempestuous affair that was in the running for Fight of the Year until eclipsed by the barnburner between Diego Corrales and Jose Luis Castillo. The SRO crowd was top-heavy with Mexican agricultural workers, an edge to Larios who won a unanimous decision.

The rematch in Las Vegas on July 16, 2005, was almost as lusty. The combatants were credited with throwing a combined total of 2,317 punches before McCullough was pulled out after 10 rounds by Freddie Roach. On the advice of ringside physician Dr. Margaret Goodman, Wayne was slapped with an indefinite suspension. McCullough was never off his feet – not in this fight, not ever — but Goodman felt that he had simply taken too many punches over the course of his career and if he continued to box, he was destined to develop serious neurological problems.

McCullough spent thousands of dollars of his own money on an extensive battery of tests and passed them all, compelling the Nevada commission to lift the suspension which it did on Feb. 1, 2006, but he never fought in the Silver State again.

—

Wayne McCullough has a wealth of memorabilia from his boxing career plastered on the walls of his gym and in his living room. Among other things, there are two signed drawings from his admirer Bono.

When we stopped by the other day, Wayne was working with the Tyndall brothers from Bray (hometown of Katie Taylor), 22-year-old Matthew (7-1 as a pro) and 19-year-old Sean (1-0). “Irish fighters, in the main,” he said, “know how to punch with authority, but lack defense. They come to me to improve their defense.”

How ironic. In his fighting days, Wayne was a whirlwind. In his prime, he wore his opponents down with non-stop aggression. Eddie Futch once compared him to Henry Armstrong. The word “defense” hardly jumps to mind when picturing his style, but perhaps it made sense – think of all the hitting coaches in baseball who weren’t good hitters.

—

In 2019, Wayne McCullough was one of three living inductees ushered into the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame in the Nevada Resident category. The others were Hasim Rahman and Cuban defector Joel Casamayor, a world title-holder at 130 and 135 pounds. Twenty-seven years after their gold medal match in Barcelona, McCullough and Casamayor stood on the same podium once again.

“I remember sitting next to Joel on a couch in the drug testing room after we fought. We spoke different languages, so we didn’t carry on a conversation. But now when I see him, we are old friends,” says McCullough. “We have that bond for life.”

The big Hall of Fame, the one in Canastota, has yet to honor Wayne, and that’s a sore spot with him. True, his final record, 27-7, isn’t up to snuff, but six of his seven setbacks, all but the last, came in world title fights, three against future Hall of Famers (Zaragoza, Hamed, and Erik Morales). In the ring he was a ball of fire and he had one of the best chins in boxing – the very best chin according to a 2000 story in The Ring magazine. And then there’s all those medals he won in international competitions as an amateur, which Wayne thinks ought to count for something. Before turning pro, he stopped Arturo Gatti and defeated two others who would go on to win world titles.

The call from Canastota may never come, but Wayne can take satisfaction in knowing he had a memorable career, has retained all his faculties, and that life after boxing has been good to him.

Patrick Myler, the noted Irish boxing writer and author, had his misgivings.

“[The McCulloughs] have been careful with their money,” wrote Myler in a 1999 story for the Dublin Evening Herald. “They say they have enough saved to live comfortably on the interest. But, even if the main attractions of the world’s gaming capital are not their scene, it can’t be cheap living there…With no special skills apart from what he does with his fists, he will find it hard to sustain a comfortable lifestyle.”

Not to worry, Mr. Myler. Wayne McCullough and the missus and their lovely daughter are doing just fine.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend