Featured Articles

Remembering Joe Frazier

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about Joe Frazier as the first anniversary of his death (November 7, 2011) approaches.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about Joe Frazier as the first anniversary of his death (November 7, 2011) approaches.

I met Joe at the Sahara Hotel in Las Vegas on December 1, 1988. I’d just signed a contract to become Muhammad Ali’s official biographer. Two days of taping were underway for a documentary entitled Champions Forever that featured Ali, Frazier, George Foreman, Ken Norton, and Larry Holmes. I was there to conduct interviews for my book.

On the first morning, I sat at length with Foreman; the pre-lean-mean-grilling-machine model. George was twenty months into a comeback that was widely regarded as a joke. Six more years would pass before he knocked out Michael Moorer to regain the heavyweight throne.

“There was a time in my life when I was sort of unfriendly,” George told me. “Zaire was part of that period. I was going to knock Ali’s block off, and the thought of doing it didn’t bother me at all. After the fight, for a while I was bitter. I had all sorts of excuses. The ring ropes were loose. The referee counted too fast. The cut hurt my training. I was drugged. I should have just said the best man won, but I’d never lost before so I didn’t know how to lose. I fought that fight over in my head a thousand times. Then, finally, I realized I’d lost to a great champion; probably the greatest of all time. Now I’m just proud to be part of the Ali legend. If people mention my name with his from time to time, that’s enough for me. That, and I hope Muhammad likes me, because I like him. I like him a lot.”

Then I moved on to Ken Norton, who shared a poignant memory.

“When it counted most,” Norton reminisced, “Ali was there for me. In 1986, I was in a bad car accident. I was unconscious for I don’t know how long. My right side was paralyzed; my skull was fractured; I had a broken leg, a broken jaw. The doctors said I might never walk again. For a while, they thought I might not ever even be able to talk. I don’t remember much about my first few months in the hospital. But one thing I do remember is, after I was hurt, Ali was one of the first people to visit me. At that point, I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to live or die. That’s how bad I was hurt. Like I said, there’s a lot I don’t remember. But I remember looking up, and there was this crazy man standing by my bed. It was Ali, and he was doing magic tricks for me. He made a handkerchief disappear; he levitated. I said to myself, if he does one more awful trick, I’m gonna get well just so I can kill him. But Ali was there, and his being there helped me. So I don’t want to be remembered as the man who broke Muhammad Ali’s jaw. I just want to be remembered as a man who fought three close competitive fights with Ali and became his friend when the fighting was over.”

Larry Holmes held out for cash, so our conversation was short: “I’m proud I learned my craft from Ali,” Larry said. “I’m prouder of sparring with him when he was young than I am of beating him when he was old.”

End of conversation.

That left Joe.

Frazier wouldn’t talk with me because I was “Ali’s man.” But at an evening party after the second day of taping, Joe approached me. He’d been drinking. And the vile spewed out:

“I hated Ali. God might not like me talking that way, but it’s in my heart. First two fights, he tried to make me a white man. Then he tried to make me a nigger. How would you like it if your kids came home from school crying because everyone was calling their daddy a gorilla? God made us all the way we are. He made us the way we talk and look. And the way I feel, I’d like to fight Ali-Clay-whatever-his-name-is again tomorrow. Twenty years, I’ve been fighting Ali, and I still want to take him apart piece by piece and send him back to Jesus.”

Joe saw that I was writing down every word. This was a message he wanted the world to hear.

“I didn’t ask no favors of him, and he didn’t ask none of me. He shook me in Manila; he won. But I sent him home worse than he came. Look at him now. He’s damaged goods. I know it; you know it. Everyone knows it; they just don’t want to say. He was always making fun of me. I’m the dummy; I’m the one getting hit in the head. Tell me now; him or me, which one talks worse now? He can’t talk no more, and he still tries to make noise. He still wants you to think he’s the greatest, and he ain’t. I don’t care how the world looks at him. I see him different, and I know him better than anyone. Manila really don’t matter no more. He’s finished, and I’m still here.”

Twenty-one months later, when I finished writing Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, I journeyed to Ali’s home in Berrian Springs, Michigan. Lonnie Ali (Muhammad’s wife), Howard Bingham (Ali’s longtime friend and personal photographer), and I spent a week reading every word of the manuscript aloud. By agreement, there would be no censorship. Our purpose in reading was to ensure the factually accuracy of the book.

In due course, Lonnie read Frazier’s quote aloud.

There was a silent moment.

“Did you hear that, Muhammad?” Lonnie asked.

Ali nodded.

“How do you feel, knowing that hundreds of thousands of people will read that?”

“It's what he said,” Muhammad answered.

Ali’s thoughts ended that chapter of the book.

“I’m sorry Joe Frazier is mad at me. I’m sorry I hurt him. Joe Frazier is a good man. I couldn’t have done what I did without him, and he couldn’t have done what he did without me. And if God ever calls me to a holy war, I want Joe Frazier fighting beside me.”

On the final day of our reading, Muhammad, Lonnie, Howard, and I signed a pair of boxing gloves to commemorate the experience. I took one of the gloves home with me. Howard took the other.

The following spring, I was in Philadelphia for a black-tie gala celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the historic first fight between Ali and Frazier. This was Joe’s night. It was a fight he’d won. But his hatred for all things Ali was palpable.

Early in the evening, Howard suggested that I pose for a photo with Muhammad and Joe. I stood between them. Joe wrapped his arm around my waist in what I thought was a gesture of friendship. Then, just as Howard snapped the photo, Joe dug his fingers into the flesh beneath my ribs.

It hurt like hell.

I tried to pry his hand away.

You try prying Joe Frazier’s hand away.

When Joe was satisfied that he’d inflicted sufficient pain, he smirked at me and walked off.

Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times was published in June 1991. Joe decided that I’d treated him fairly. In the years that followed, when our paths crossed, he was warm and friendly. A ritual greeting evolved between us.

Joe would smile and say, “Hey! How’s my Jewish friend?”

I’d smile and say, “Hey! How’s my Baptist friend?”

Fast-forward to January 7, 2005. Joe was in my home. We were eating ice cream in the kitchen.

Three boxing gloves were hanging on the wall. The first two were worn by Billy Costello in his victorious championship fight against Saoul Mamby. That fight has special meaning to me. It’s the subject of the climactic chapter in The Black Lights, my first book about boxing.

The other glove bore the legend:

Muhammad Ali

Lonnie Ali

Howard L. Bingham

Thomas Hauser

9/10 – 9/17/90

Joe asked about the gloves. I explained their provenance. Then he said something that surprised me.

“Do you remember that time I gave you the claw?”

“I remember,” I said grimly.

“I’m sorry, man. I apologize.”

That was Joe Frazier. He remembered every hurt that anyone ever inflicted upon him. With regard to Ali, he carried those hurts like broken glass in his stomach for his entire life.

But Joe also remembered the hurts he’d inflicted on other people. And if he felt he’d done wrong, given time he would try to right the situation.

There’s now a fourth glove hanging on the wall of my kitchen. It bears the inscription:

Tom, to my man

Right on

Joe Frazier

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at thauser@rcn.com. His most recent book (And the New: An Inside Look at Another Year in Boxing) was published by the University of Arkansas Press.

Featured Articles

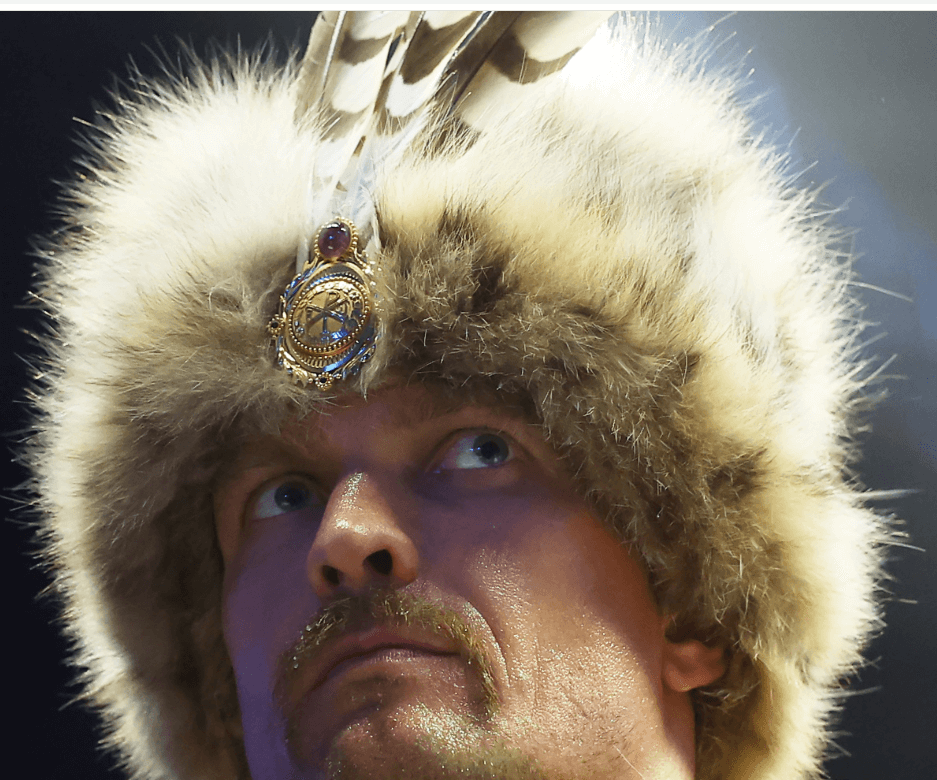

Oleksandr Usyk is the TSS 2024 Fighter of the Year

Six years ago, Oleksandr Usyk was named the Sugar Ray Robinson 2018 Fighter of the Year by the Boxing Writers Association of America. Usyk, who went 3-0 in 2018, boosting his record to 16-0, was accorded this honor for becoming the first fully unified cruiserweight champion in the four-belt era.

This year, Usyk, a former Olympic gold medalist, unified the heavyweight division, becoming a unified champion twice over. On the men’s side, only two other boxers, Terence Crawford (light welterweight and welterweight) and Naoya Inoue (bantamweight and super bantamweight) have accomplished this feat.

Usyk overcame the six-foot-nine goliath Tyson Fury in May to unify the title. He then repeated his triumph seven months later with three of the four alphabet straps at stake. Both matches were staged at Kingdom Arena in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Fury was undefeated before Usyk caught up with him.

In the first meeting, Usyk was behind on the cards after seven frames. Fury won rounds 5-7 on all three scorecards. It appeared that the Gypsy King was wearing him down and that Usyk might not make it to the finish. But in round nine, the tide turned dramatically in his favor. In the waning moments of the round, Usyk battered Fury with 14 unanswered punches. Out on his feet, the Gypsy King was saved by the bell.

In the end the verdict was split, but there was a strong sentiment that the right guy won.

The same could be said of the rematch, a fight with fewer pregnant moments. All three judges had Usyk winning eight rounds. Yes, there were some who thought that Fury should have been given the nod but they were in a distinct minority.

Usyk’s record now stands at 23-0 (14). Per boxrec, the Ukrainian southpaw ended his amateur career on a 47-fight winning streak. He hasn’t lost in 15 years, not since losing a narrow decision to Russian veteran Egor Mekhontsev at an international tournament in Milan in September of 2009.

Oleksandr Usyk, notes Paulie Malignaggi, is that rare fighter who is effective moving backwards or forwards. He is, says Malignaggi, “not only the best heavyweight of the modern era, but perhaps the best of many…..At the very least, he could compete with any heavyweight in history.”

Some would disagree, but that’s a discussion for another day. In 2024, Oleksandr Usyk was the obvious pick for the Fighter of the Year.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

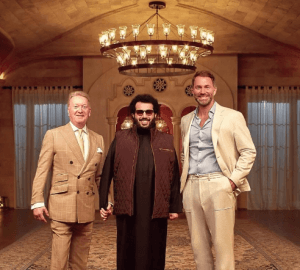

A No-Brainer: Turki Alalshikh is the TSS 2024 Promoter of the Year

Years from now, it’s hard to say how Turki Alalshikh will be remembered.

Alalshikh, the head of Saudi Arabia’s General Entertainment Authority, isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. Some see him as a poacher, a man who snatched away big fights that would have otherwise landed in places like Las Vegas, New York, and London, and planted them in a place with no prizefighting tradition whatsoever merely for the purpose of “sportswashing.” If that be the case, Alalshikh’s superiors, the royal family, will turn off the spigot once it is determined that this public relations campaign is no longer needed, at which time the sport will presumably recede into the doldrums from whence it came.

Be that as it may, there is no doubt that boxing is in much better shape today than it was just a few years ago and that Alalshikh, operating under the rubric of Riyadh Season, is the reason why.

One of the most persistent cavils lobbied against professional boxing is that the best match-ups never get made or else languish on the backburner beyond their “sell-by” date, cheating the fans who don’t get to see the match when both competitors are at their peak. This is a consequence of the balkanization of the sport with each promoter running his fiefdom in his own self-interest without regard to the long-term health of the sport.

With his hefty budget, Alalshikh had the carrot to compel rival promoters to put down their swords and put their most valuable properties in risky fights and he seized the opportunity. All of the sport’s top promoters – Frank Warren and Eddie Hearn (pictured below), Bob Arum, Oscar De La Hoya, Tom Brown, Ben Shalom, and others – have done business with His Excellency.

The two most significant fights of 2024 were the first and second meetings between Oleksandr Usyk and Tyson Fury. The first encounter was historic, begetting the first undisputed heavyweight champion of the four-belt era. Both fights were staged in Saudi Arabia as part of Riyadh Season, the months-long sports and entertainment festival instrumental in westernizing the region.

The Oct. 12 fight in Riyadh between undefeated light heavyweights Artur Beterbiev and Dmitry Bivol produced another unified champion. This wasn’t a great fight, but a fight good enough to command a sequel. (Beterviev, going the distance for the first time in his pro career, won a majority decision.) The do-over, buttressed by an outstanding undercard, will come to fruition on Feb. 22 in Riyadh.

Turki Alalshikh didn’t do away with pay-per-view fights, but he made them more affordable. The price tag for Usyk-Fury II in the U.S. market was $39.99. By contrast, the last PBC promotion, the Canelo vs. Berlanga fight on Amazon Prime Video, carried a tag of $89.95 for non-Prime subscribers.

Almost half the U.S. population resides in the Eastern Time Zone. For them, the main event of a Riyadh show goes in the mid- to late-afternoon. This is a great blessing to fight fans disrespected by promoters whose cards don’t end until after midnight, and that goes double for fight fans in the U.K. who can now watch more fights at a more reasonable hour instead of being forced to rouse themselves before dawn to catch an alluring match anchored in the United States.

In November, it was announced that Alalshikh had purchased The Ring magazine. The self-styled “Bible of Boxing” was previously owned by a company controlled by Oscar De La Hoya who acquired the venerable magazine in 2007.

With the news came Alalshikh’s assertion that the print edition of the magazine would be restored and that the publication “would be fully independent.”

That remains to be seen. One is reminded that Alalshikh revoked the press credential of Oliver Brown for the Joshua-Dubois fight on Sept. 21 at London’s iconic Wembley Stadium because of comments Brown made in the Daily Telegraph that cast a harsh light on the Saudi regime.

There were two national anthems that night, “God Save the King” sharing the bill, as it were, with the Saudi national anthem. Considering the venue and the all-British pairing, that rubbed many Brits the wrong way.

The Ring magazine will always be identified with Nat Fleischer who ran the magazine from its inception in 1922 until his death in 1972 at age 84. It was written of Fleischer that he was the closest thing to a czar that the sport of boxing ever had. Turki Alalshikh now inherits that mantle.

It’s never a good thing when one man wields too much power. We don’t know how history will judge Turki Alalshikh, but naming him the TSS Promoter of the Year was a no-brainer.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

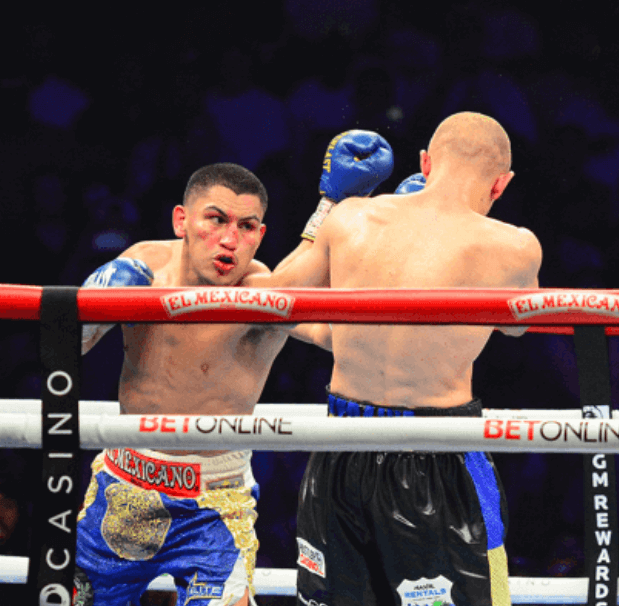

The Ortiz-Bohachuk Thriller has been named the TSS 2024 Fight of The Year

The Aug. 10 match in Las Vegas between Knockout artists Vergil Ortiz Jr and Serhii Bohachuk seemingly had scant chance of lasting the 12-round distance. Ortiz, the pride of Grand Prairie, Texas, was undefeated in 21 fights with 20 KOs. Bohachuk, the LA-based Ukrainian, brought a 24-1 record with 23 knockouts.

In a surprise, the fight went the full 12. And it was a doozy.

The first round, conventionally a feeling-out round, was anything but. “From the opening bell, [they] clobbered each other like those circus piledriver hammer displays,” wrote TSS ringside reporter David A. Avila.

In this opening frame, Bohachuk, the underdog in the betting, put Ortiz on the canvas with a counter left hook. Of the nature of a flash knockdown, it was initially ruled a slip by referee Harvey Dock. With the benefit of instant replay, the Nevada State Athletic Commission overruled Dock and after four rounds had elapsed, the round was retroactively scored 10-8.

Bohachuk had Ortiz on the canvas again in round eight, put there by another left hook. Ortiz was up in a jiff, but there was no arguing it was a legitimate knockdown and it was plain that Ortiz now trailed on the scorecards.

Aware of the situation, the Texan, a protégé of the noted trainer Robert Garcia, dug deep to sweep the last four rounds. But these rounds were fused with drama. “Every time it seemed the Ukrainian was about to fall,” wrote Avila, “Bohachuk would connect with one of those long right crosses.”

In the end, Ortiz eked out a majority decision. The scores were 114-112 x2 and 113-113.

Citing the constant adjustments and incredible recuperative powers of both contestants, CBS sports combat journalist Brian Campbell called the fight an instant classic. He might have also mentioned the unflagging vigor exhibited by both. According to CompuBox, Ortiz and Bohachuk threw 1579 punches combined, landing 490, numbers that were significantly higher than the early favorite for Fight of the Year, the March 2 rip-snorter at Verona, New York between featherweights Raymond Ford and Otabek Kholmatov (a win for Ford who pulled the fight out of the fire in the final minute).

Photo credit: Al Applerose

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoR.I.P Israel Vazquez who has Passed Away at age 46

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoA Shocker in Tijuana: Bruno Surace KOs Jaime Munguia !!

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFighting on His Home Turf, Galal Yafai Pulverizes Sunny Edwards

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoThe Ortiz-Bohachuk Thriller has been named the TSS 2024 Fight of The Year

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIntroducing Jaylan Phillips, Boxing’s Palindrome Man

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 306: Flyweight Rumble in England, Ryan Garcia in SoCal

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoUsyk Outpoints Fury and Itauma has the “Wow Factor” in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

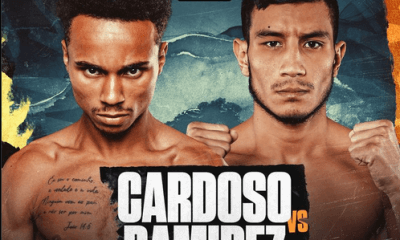

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCardoso, Nunez, and Akitsugi Bring Home the Bacon in Plant City