Featured Articles

We Should Have PROOF Before We Label Marquez A Cheater…Shouldn’t We?

People smelled smoke, and assume that there is fire, and it was lit by Heredia, at Marquez’ behest. But…don’t we need more than circumstantial evidence to decide this is so? (Chris Farina-Top Rank)

Americans are big fans of conspiracy theories these days. Not a tremendous surprise; during tough times, some cling to religion, some to guns, and some to whacky, unproven narratives which help to tame the insecurities rife in their heads.

The other day, I was in my favorite coffee shop, talking with a young lady working behind the counter. The topic of guns, and the culture of violence, the casual acceptance of regular shootings, was being discussed.

The young lady dropped her voice and made an admission to me. “I think that shooting at that theater in Colorado, I think that guy was set up.”

“Wait…the killing of 12 innocents who went to see the new Batman movie in Aurora, Colorado in July by a nut named James Holmes…you think he didn’t do it, and was set up?”

Holmes was apprehended at the theater, in his warrior gear, and told cops, it was reported, that he’d booby trapped his apartment so they’d get blown up after he got locked up. He has not denied that he went on this murderous rampage.

Now, I wasn’t able to decipher why my barista friend is ignoring what looks like overwhelming evidence that Holmes was the lone gunman who committed this atrocious act. But this situation came to mind the day after Saturday’s KO shocker, win which 39 year-old Juan Manuel Marquez dropped and stopped Manny Pacquiao as if he tazed him at the MGM in Las Vegas.

Whispers turned to screams that this thing wasn’t on the up and up, that Marquez surely was juicing, that the result was tainted because…why, again? I waited for some evidence. I searched for a concrete, or even a semi concrete explanation why so many folks were fixated on PEDS in the aftermath of the fight of the year.

Instead of “concrete” I found and heard circumstantial chatter. Mostly, the “Marquez cheated” crew seems to focus on the presence of his strength and conditioning coach, Angel Heredia. The fighter hired Heredia before his third fight with Pacquiao, and has now used his services for three fights. The stern eyed crew points out that Heredia has a dirty–filthy, actually–past, as a peddler of steroids and other chemicals taken to improve performance during athletic events. When pinched for being a pusher to world class athletes, Heredia rolled over, received immunity from the Feds, and helped put away Trevor Graham, coach to elite sprinters Marion Jones and Tim Montgomery. Back then, Heredia was described as a Texas resident, and shot-putter who got roids in Mexico, and then doled them out to other athletes. Graham was described when that scandal blew up, in 2006, by his defenders as a whistleblower who sent a syringe of a designer PED dispensed by the notorious Victor Conte out of his BALCO shop in San Francisco to the US Anti-Doping Agency. That alert some said caused the investigation which snagged Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire and other MLB long-ball artists in a snare to snag cheaters.

Now, as far as circumstantial evidence goes, Heredia admittedly is a sweet target for smack talk. The guy is a rat, who gave up friends and associates, so he’d get off easier in the eyes of the law. When he re-appeared on radar screens as Marquez’ coach, he was using a different name, for cripes sake; he was calling himself “Angel Hernandez.” Memories were refreshed, and Conte spread the word that Heredia got off scot free, and did no time, while he was sent to jail for four months for his involvement in illegal chemical performance enhancers. MaxBoxing’s dogged anti-doping crusaders Gabriel Montoya before the fourth Pacquiao-Marquez fight alerted people to a German documentary which features Heredia injecting a PED into his own belly, on camera, and then going into a pharmacy in Mexico and buying PEDs over the counter and then concocting a syrup which will aid performance and then not get flagged by drug testers. (It is not clear what Heredia had to gain by pointing out how simple it is to score PEDs and administer them. Was he compensated to appear in the doc? Was he simply bragging, portraying himself as a mover and shaker in sports, someone who is tacitly responsible for the superior performances offered by our heroes? Was he trying to wake us all up to the overwhelming prevalence of PEDs in basically all big-time sports?)

Further circumstantial evidence offered by those who feel there is a humongous black cloud over the Marquez win? They point to the weak performance by Marquez in his loss to Floyd Mayweather in 2009, and the bulbous shoulder muscles and over-all sterling physique he now boasts. And as of Sunday morning, they point to a newfound level of power possessed by Marquez that wasn’t, they say, present before. That single shot, that right counter which felled Pacquiao, was just too good to be true, they are saying. Oh, and what about that acne on Marquez, they say, isn’t that damning?

How in God’s name could a 39-year-old man, 12 or so year’s after the average male’s physical gifts begin to deteriorate, improve so dramatically at such a late stage.

These are all good questions, great questions…but we need answers, in the form of proof, smoking gun level, irrefutable proof, before we smear Marquez, or Heredia.

Is it fishy that Marquez showed a heretofore unseen brand of power against Pacquiao? The true believer in me, the part of me who wants to believe in the goodness that is there, even if buried, in most souls, doesn’t want to leap to conclusions. I prefer to believe that Marquez doesn’t cheat, that hard work and overwhelming desire and clean methods in training him brought him to victory Sunday. Maybe I am naive; I admit that possibility must be explored. Maybe, after all the dirt that has been laid out, all the positives, all the seemingly ludicrous explanations offered by the boxers who were busted, maybe I need to wake up, smell the stink in the air, and assume that the majority of the top tier performers are using illegal performance enhancers to get ahead.

But I’d rather all of us stopped trafficking in theories, and instead focused on reality. Until PROVEN otherwise, I think we should assume that Marquez didn’t cheat. I think we should embrace the reaction of Team Pacquiao and Manny, who congratulated Marquez for a job well done. (Will some of you assume that Pacquiao is able to clap Marquez on the back because you think he too uses chemicals to aid his strength and stamina, and thus, he feels the two were on an even playing field at the MGM in their fourth fight? Yes. Can part of me understand that urge? Again, yes.)

I am not condemning anyone for yelling fire, really, because smoke has been wafting. But our society has become all too willing to substitute facts and theory and gut instincts for proof, and dispense those theories all over the world in 140 characters or less.

Happily, there are bulldogs like Montoya who have the time, energy, effort and principles to pursue this most pressing issue in our game. I do hope that the continuing investigations into the usage of PEDs in the sport yield facts that cannot be explained away, or dismissed with doctors’ “the dog ate my homework” type notes. Because this sort of black cloud that is dumping a toxic rain of doubt and cynicism on this Fight of the Year diminishes the impact and intensity of the drama. I can only urge the power brokers in the game, the HBOs, Showtimes, Arums, Schaefers, et al, to solve this issue, and embrace random testing for the biggest of the big bouts, so we can cease the whispering and dispel that cloud of suspicion which now helps erode the enjoyment we derive from watching the best athletes in the greatest sport known to man do their thing.

Readers, weigh in with your suggestions on how to solve the PED problem. Hey, maybe you think that PEDs should be allowed and regulated, assuming that the cheaters will always be ahead of the good guys and the testers, so we should capitulate to sad reality and proceed accordingly. Go to our Forum, and add your three cents.

Follow me on Twitter here https://twitter.com/#!/Woodsy1069.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThomas Hauser’s Literary Notes: Johnny Greaves Tells a Sad Tale

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoUndercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

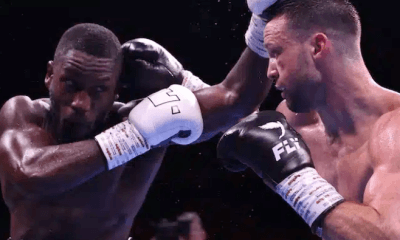

Featured Articles1 week agoEkow Essuman Upsets Josh Taylor and Moses Itauma Blasts Out Mike Balogun in Glasgow

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks ago“Breadman” Edwards: An Unlikely Boxing Coach with a Panoramic View of the Sport