Featured Articles

Rest In Peace, Johnny Bos

His skill at choosing a succession of opponents to help a boxer travel from professional point A to point B was immense. His skill at playing life as a politician, of tamping down his voracious need to speak truth to power, to broadcast his critiques of the sport of boxing, was not present to the same extent. Johnny Bos, a Sunset Park, Brooklyn-bred boxing lifer, died in his Clearwater, Florida residence on Saturday. He was 61 years old, and did it his way to the final day.

Bos (pronounced Boz) dealt with congestive heart failure for many years, and I think it’s fair to say that the news of his death, for many that knew him, and knew how deeply he felt the sting of not being in the big-league mix that his talent and acumen suggested he should be, was met with a mixed emotions.

This XL character–he was 6-4, north of 250 pounds, prone to wearing hip hop and pimp-ish gear– was something of a tortured soul. He had a pathological need to diagnose the ills he saw riddling the sport and broadcast his critiques to the world. At the same time, in more recent years, he wanted to be back on the big stage, in NYC, fashioning the paths of prospects to the big time. For a years, I’d try and gently counsel him to adjust his expectations and subvert his iconoclastic tendencies, so he might be accepted back into the club which he bitterly railed had spurned him.

“Johnny,” I’d say, “it makes it harder for the big shots to bring you back into the fold when you say controversial things, and are too honest.”

But he was pathologically incapable of self-censorship. The truth wasn’t something to be dispensed selectively. He couldn’t pick and choose his spots, modulate his delivery to minimize the damage to the ego of the guilty. He couldn’t, he wouldn’t, and for that he must be praised, and his passing must be lamented with more fanfare than his level of celebrity typically enjoys.

Johnny’s laundry list of the dirt in the game was nearly never ending, and his recitation of the ills kept him from rising back from club-show levels onto the A grade cards, with the A grade checks to go with it. Perhaps he knew that railing against the New York State Athletic Commission’s mishandling of the Arturo Gatti weigh-in prior to his February 26, 2000 fight against his guy Joey Gamache was a signed death warrant against his re-admission into the club, but that didn’t affect his outlook. And that was to his immense credit; in a sport which desperately needs healers willing to diagnose and attack the malignancies, Bos fit the bill–and he paid dearly for his candor.

Bos, with that immense frame and theatrical manner of conversing left the impression to new acquaintances unaware of his reason for being that perhaps professional wrestling was his ouevre. But no, boxing was his lasting love, and had been since he laid eyes on the sport which seduced him. Before he hit puberty, Bos was skipping school and instead roaming the dozens of fight gyms which dotted the boroughs. He went from super-fan, to news-sheet writer and hawker, and began making matches in 1977. He worked for Main Events, and Brit Mickey Duff, and steered the ship on the earliest voyages of Gerry Cooney and Mike Tyson. Bos knew which icebergs to steer clear of, and, pals knew, wasn’t shy about telling the world of his prowess. Perhaps he felt the need to inform or remind us of his skills because his circumstances, in later years, didn’t give a hint of his sagacity. To stay afloat, he’d sell memorabilia and you couldn’t blame the guy if he’d pointed to himself as Exhibit B in why the sport needed to be structured differently so lifers could have a pension to look forward to. I got the sense that it was probable that he never compromise his ways, and that he wouldn’t forgive or forget the transgressions of those that had wronged him. When a Facebook post indicated that he was counting down the days until his sentence was served, until he went to a better place, I’d shake my head, maybe, and wonder why he couldn’t steer out of that place. Sometimes, I’d ponder what my father told me about my own mom, someone who also had a hard time finding silver linings: “Mike, mom won’t be truly happy until she’s in heaven.”

Bos didn’t comprehend why, if he was the guy who’d developed more world champions that any soul on earth, as was his claim, the power brokers didn’t utilize his services. I told him a few times that was because he was too truthful and that such honesty, while admirable in the abstract, would hold him back. “Johnny, if you’re telling writers that the New York State Athletic Commission is a corrupt institution, than that makes it basically impossible for a promoter in this region to bring you on,” I’d say. He wouldn’t accept, at least not out loud, that his honesty could be the thing holding him down. And bless his soul for that. That is such a rare trait; the majority of us sell out on a daily basis, refusing to write about this scandal, or call out that dirtbag, because we fear ramifications, fear being marginalized, worry about being booted from the club. Johnny’s disgust at the way the game was played probably didn’t do anything for his longevity. Yes, those periodic posts on Facebook, promising comeuppance for those who’d wronged him in the past, left friends worrying somewhat for his state of mind. He seemed incapable of letting go, but when you dug down, and really thought about all the guys that ditched him at the altar when it came to get hitched, you realized that he had grounds for his rancor.

Friends would tell him to embrace the concept of the contract but he’d blow it off. I’d start to offer him the definition of insanity, lobby him to see that doing the same action again and again and expecting different results would continue to harden his heart, but as the years passed, my counseling waned, and then ended. Johnny was going to do what he was going to do, his compass was locked in, I realized, and couldn’t be budged.

He told us he’d been blackballed in New York, and none of us fought that assertion, I don’t think. No one needed to search for a smoking gun memo to prove his point. We knew that trying to sue Floyd Patterson for taking over his kid’s career after Bos did the steering, and later joining with Gamache in suing the state for botching the Gatti weigh in, that those actions would disqualify him from getting back in the New York groove. But his compass pointed toward truth, to his frequent detriment, and you got the sense that would be his direction till the end.

Opining that boxing was better off when the crooked nose crew ran the racket, even if he didn’t explicitly call out the worst actors in the highest echelons, meant that in later years, Bos would need to get by on low-money gigs for smaller fry promoters. I should have, looking back, allowed him a platform more often in recent years, given him the space and amplifier to inform or remind fans that it was shameful how wages have stagnated for boxers, how more money trickled down to the lesser lights when Carbo had a grip on the game, than today. People like me would nod and mouth unenthused agreement when he griped that onerous promotional deals were hurting the game. It could become repetitious…but that’s as it should have been, as it was our own damn fault we didn’t apply the salves he prescribed.

He’d say that managers were a dying breed, that promoters held all the cards, and you needed to play ball with them if you wanted to get along. Because promoters liked to match their guys soft, to get to a lofty place without bruising them along the way, that meant that his old-school style of matching guys tough went the way of the dinosaur. yes, Johnny was as subtle as a Brontosaurus and I should have given him the space to hear his roar much more often.

Other things Bos railed against, which should be mentioned, in deference to the man…He didn’t care for the lack of available facilities, those hole in the wall gyms which gave street kids an option other than the streets, in recent decades. The sport became an option for rich kids only, with the gym dues, necessary because of our national real estate bubble, becoming prohibitive, he’d say. Oh, and the gloves, they have less padding in them today, and that’s why you get more hand injuries. Really, there wasn’t an area of the sport where Bos didn’t see a hole that needed patching.

Bos actually struck a blow against mainstream societal ills which leave 98% of our citizens with a state of income inequality unseen since before the Great Depression. He saw that outsized medical bills for boxers needing to comply with commissions to get or re-apply for their license hit the have nots hard and acted as a deterrent to participation for many. The same scenario plagues have nots in the realm of higher education, you will note. Johnny’s prescriptions for betterment, I realize looking back, would well apply to the world as a whole, not just the world of boxing.

Johnny was a big fan of the Rage Against the Machine song “Killing in the Name,” which features the lyrics, “F–k you, I won’t do what ya tell me” repeated again and again. He lived the lyric, and didn’t care what toes he broke when he smashed his heels down for emphasis when discussing boxing’s moribund amateur scene. The lack of vitality there was a constant theme, as was the flattening of the globe. The fall of communism meant free enterprise opened up in Eastern Europe and that meant opportunities for Americans to travel overseas to earn a decent payday lessened, because Euros were willing to fight for a lesser fee. The big two, HBO and Showtime, were in Johnny’s bulls-eye all the time, as he believed they owned too much power, as they controlled the purse strings and thus were able call too many shots. They acted as promoter, matchmaker and broadcaster, he said, so guys like him lost their voice. And the promoters, back to them. They just took TV money now, didn’t have to hustle to put asses in seats, so they coasted, and the sport suffered. Bos knew there was no inducement to build the brand of boxing now, and as a result, the “boxing is dying” meme has been flourishing for 25 or more years.

Johnny would tell you he got stiffed more and more as the decades progressed, that while a handshake used to be good enough, that bond of flesh-and-word had disintegrated. In truth, as his power waned, people did indeed take advantage of his diminished stature. They know who they are, and Johnny would like it if their consciences would admit, at least in private, in the night when darkness allowed them cover to feel the guilt and shame, that they screwed him.

Maybe he didn’t present his ideas with the polish, with a political sheen that would have made them and him more palatable, but nobody with a heart could take issue with his frequent suggestion to put 1% of US revenue from the sport, especially from those mega-grossing pay-per-views, into a pot to help pay for the medical expenses of boxers down the line. If all of us listened to Johnny more, and applied the medicine he knew was needed to heal the ills of the game, the sport would be far better off. Sorry, Bos.

I’m sorry I sometimes tuned you out, because a diet of too much truth was hard to handle for me. That is to my discredit, my man. I will try and do my small part and rail about your pet peeves now and again, because you had it right. Our citizens, and the residents of Box Nation, often fall into a complacent state, and choose “serenity” and acceptance and a constant stream of rationalizations, instead of trafficking in truth and seeking necessary change. You were an influence on me more than I told you, and I apologize for not telling you that. Thanks for your predictions and anecdotes and rambling phone calls. The rambling was, looking back, delightful.

See ya!

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles2 days ago

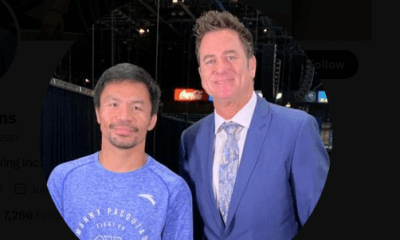

Featured Articles2 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons