Featured Articles

Atlantic City Gala Recalls Good Times Perhaps Lost Forever

The mostly middle-aged crowd at 23 East, a bar in Ardmore, Pa., on Philadelphia’s Main Line, was clearly into the live rock ’n’ of a stage show headlined by Tommy Conwell, the front man for a popular local group from the 1980s, Tommy Conwell & the Young Rumblers.

“The ’80s are coming back!” Conwell yelled into the microphone, to the approval of his relatively small but enthusiastic audience. And maybe that really can be the case to some degree. There always are going to be music lovers who choose to remain rooted in the sounds of their youth because, well, thinking of the Young Rumblers as still being young is a convenient way of forgetting the graying or thinning of their own hair, or the formation of spare tires around their waists and those worrisome crow’s feet around their eyes.

One night later and 65 miles to the East, there was a similar celebration of what was. The second annual Atlantic City All Stars Boxing Gala at Resorts Casino Hotel, in a sense, was like a gathering of members of the Flat Earth Society. There had been good times for boxing in the ’80s along the boardwalk, and plenty of them, but good times and those who helped make them happen have a way of slipping away with the passage of time. Aging boxers are in their own way like Young Rumblers whose rumbling now is mostly confined to memory. When the hits stop coming, what alternative is there but to recycle past glories?

“There are mixed emotions,” admitted Jonathan Diego, the former Atlantic City prosecutor who conceived the black-tie-optional event and serves as its chairman and foremost cheerleader. “`Bittersweet’ is a good word to describe it. It’s sweet that you can get 50 former champions , referees and judges in the same room. The bitter part is that we don’t have as many big fights, world championship fights, in Atlantic City as we once had.”

Ken Condon, the Sports and Entertainment consultant for Caesars Entertainment, has waved the banner for Atlantic City boxing even longer than Diego (he was there, in the marketing department, when Resorts became the first A.C. casino to open its doors in 1978), and just as passionately. He sees a pinpoint of light at the end of what for years had been an ever-darkening tunnel.

“Boxing is cyclical,” said Condon, one of a group of award recipients Saturday night that included, among others, former world champions Virgil Hill (who’ll be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame on June 9), Iran Barkley, William Joppy, Keith Holmes, Cory Spinks, DeMarcus Corley and contenders Chuck Wepner, Ivan Robinson, Jameel McCline and John Scully. “Atlantic City has always been receptive to good boxing. I think more (casino) properties are starting to add boxing to their marketing programs. Things are getting a little better in that respect. But we have a ways to go yet.”

If the rate of fight cards continues to hold through 2013, there is a strong likelihood double-digits will be reached, with the total number of shows topping out somewhere between 15 and 20. Even as honorees strode to the podium to accept their plaques from Diego and master of ceremonies Mike Mittman, less than a mile down the boardwalk there was a J Russell Peltz-promoted card headlined by junior welterweight Teon Kennedy’s 10-round unanimous decision over Carlos Vinan.

But while a 20-fight-card year might seem puny in comparison to the early- to mid-1980s, when Atlantic City averaged 130 shows from 1982 to 1985, when it was the site of a staggering 145 events, it is a damn sight better than the even punier five cards that were staged in the erstwhile capital of East Coast boxing in 2009, which marked the sport’s nadir down the shore.

So what happened? How could something so, well, great do an about-face and march backward toward near-irrelevance? Everyone has his own theory on the rise and fall of Atlantic City boxing.

“In the late 1970s, all through the ’80s and even into the ’90s, there was a level of success you almost couldn’t expect,” said Roy Foreman, George Foreman’s younger and shorter brother who for a quarter-century has split his time between his Texas and New Jersey residences. “We knew there would have to be a lull, eventually.

“I hope more people, influential people, begin to realize that boxing built Atlantic City. I don’t mean the actual buildings, but fight fans poured into this town for boxing matches. That’s why they came for, not just for the gambling. They came from New York, they came from Philadelphia, they came from Washington. And they didn’t just come to see superstars like Mike Tyson and George. A lot of fighters made their reputations here, and they developed their own followings.

“Now, the city is hurting. We have to find a way to do whatever it takes to bring it back to what it was, or somewhere near to what it was. The main problem is taxes. We need to get Gov. Christie and the legislature to give boxing some sort of tax break to make things more attractive to fighters and promoters. Guys would love to fight here more. Floyd Mayweather told me one of the best times he had was when he came here (to fight Arturo Gatti).”

Diego is mindful of the obstacles between the still-bleak current reality and a new dawn of progress. Not only is the economy gelatin-soft, but the cost of doing business is getting steeper, as is the competition from neighboring states that have legalized casino gambling to the detriment of Atlantic City’s 12 casinos, some of which are losing their battles with the bottom line. It’s hard to argue with such depressing facts as the 42 percent in lost casino revenues (from $5.2 billion to barely $3 billion) since 2006, at a time when casino revenue for the United States as a whole has increased 4.8 percent. Some 10,300 Atlantic City casino jobs have disappeared through layoffs and attrition, and the bad news could get worse when online gambling in Delaware goes into effect in the fall.

Joe Lupo, the senior vice-president of operations for one of Atlantic City’s glitziest casino properties, the Borgata, told the Philadelphia Inquirer that “the Jersey shore will never be quite the same due to the fact we are completely surrounded by gaming on all sides.”

So how boxing stage a comeback amid the overall chaos enveloping Atlantic City as a whole? Well, there are steps that might be taken, if only the powers that be choose to take them.

One is to identify a headliner, an Arturo Gatti type, who can become the city’s franchise fighter as was the late, great blood-and-guts brawler – who will be posthumously inducted into the IBHOF on June 9 – when he regularly packed Boardwalk Hall.

“In the ’80s boxing was at its height with Tyson and all those big stars that regularly appeared here,” Condon said. “I do think you’re going to see more and more boxing shows every year here. What I’ve tried to do is to find East Coast fighters who can develop a following and who want to make Atlantic City their boxing home. Obviously, we were able to do that very successfully with Arturo.

“Look, Mayweather-level fights are few and far between. They usually wind up in Vegas, anyway. We’re always hopeful we can find the next Arturo Gatti.”

To Diego, whose uncle is former middleweight contender Dave Tiberi, the solution could be as simple as giving up some money on the front end to make more on the back end.

“I don’t think some of these entertainment directors really understand the fight game and how boxing can benefit their properties,” he said. “Their predecessors did.

“A big part of the issue is cost. The reality is that staging boxing now costs a lot of money. Back in the day, you’d get a four-corner deal where a promoter would get the venue and hotel rooms for the fighters and their cornermen for free. The casinos just presumed they would get that money, and more, from fans (patronizing) their casinos and restaurants.

“Now those same properties are asking promoters to pay for everything. It’s cost-prohibitive for smaller- and medium-sized shows.”

The downside took some time to develop, just as the upside did. Casino gambling was approved by New Jersey voters in 1976, and Resorts – then known as Merv Griffin’s Resorts – opened with great fanfare on May 26, 1978. Two years later, French director Louis Malle’s 1980 film Atlantic City, starring Burt Lancaster and Susan Sarandon, depicted not only the extent of the resort town’s decades-long deterioration, but the steps taken to restore its former opulence with the erection of the gambling palaces that began to rise like so many steel skeletons. It was a transitional period from one era to the next, and with it the hope for a brighter tomorrow.

Make no mistakes, part of the vision was the realization of what boxing had meant to Las Vegas’ Caesars Palace, which opened in 1966, and to the neon-bathed desert outpost as a whole. Nudged by financier and casino owner Donald Trump, city fathers began to hype Atlantic City as the “boxing capital of the world.”

“It became very competitive between us and Vegas, maybe even a little contentious,” Larry Hazzard Sr., the chairman of the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board, from 1985 to 2007, said in 2009. “But we had the edge because we had Tyson.”

Mike Tyson, for those with short memories or are too young to remember, once was as big or bigger than basketball’s Michael Jordan or golf’s Tiger Woods. His status as an Atlantic City icon began modestly – with eight appearances mostly in ballroom settings when he was gaining notoriety as a young knockout artist – but it gained traction soon after Trump threw truckloads of money at him to become the marquee attraction in Boardwalk Hall, and the face of Trump’s ambitious boxing operation headquartered at Trump Plaza.

Tyson fought five times in Atlantic City after he became heavyweight champion for the first time, but the biggest night of all for him, and for boxing on the boardwalk, was June 27, 1988, when he squared off against fellow unbeaten Michael Spinks.

Let Spinks’ manager, the loquacious Butch Lewis (who was 65 when he died on July 23, 2011), explain just how wild a scene it was the night Atlantic City boxing reached its absolute apex.

“It was the biggest event in the world at that time – not just in this country or in boxing,” Lewis recalled in 2009. “I’m talking the whole bleepin’ world. If there was a Superdome in Atlantic City, we could have filled that sucker up twice over. The demand for tickets was just crazy. (The announced attendance was a sold-out 21,785.)

“I was getting calls from everybody you could think of – superstar athletes, big-time entertainers, politicians, right up to the White House. `Butch, you gotta get me in,’ they all said. But there wasn’t anything I could do. Ringside tickets had a face value of $1,500 – remember, this is 1988 dollars we’re talking about – and they were being scalped for more, a lot more, and that’s only if the people lucky enough to have ’em were willing to sell, which they weren’t.

“Anyway, Richard Pryor calls and tells me he’ll do anything to get in. Richard and me were close, so I had to try, right? I checked around, called in some favors and, somehow, I got him two tickets somewhere in the first three rows, right behind Magic Johnson.

“The fight happens. Slim (Spinks) gets knocked down in the first round. Even before he went down, Magic stood up. Boom, boom, the fight ends just like that (after an elapsed time of 91 seconds). Richard calls me later and says he never saw a punch, all he saw was Magic Johnson’s back.

“Richard is yelling, `Bleeper-bleeper, I could just as well have stayed home!’” Lewis, cracking himself up, said in replicating Pryor’s frantic, profane indignity. “But you know what? At least Richard was in the house. That was one night when you had to be there. And if you couldn’t actually be in the arena, you at least had to be in Atlantic City, taking in the wild scene. All the hotels had closed-circuit telecasts and those sold out, too.

“People who couldn’t get into Boardwalk Hall were milling around outside and offering hundreds of dollars for ticket stubs to the people who were coming out after the fight ended. They were willing to pay good money for stubs! I never saw or heard anything like that before. But, in a way, I understood. They wanted to be able to go back to wherever they came from and tell their friends and co-workers, `See, I was there.’”

But nothing lasts forever, not for Tommy Conwell or Mike Tyson, or for municipalities either. Not only did boxing begin to lose prominence in Atlantic City, but the Miss America Pageant relocated to Las Vegas in 2006. (Miss America 2014 will be crowned in Boardwalk Hall on Sept. 15, the first in a three-year return engagement in its ancestral home.) The famous diving horses at the Steel Pier stopped diving in 1978. Even finding a saltwater taffy shop along the boardwalk isn’t as easy as it once was.

So now those who would at least partially restore Atlantic City boxing peer into an uncertain future, aware of the impediments that still exist but steadfast in their shared belief that progress is being made, if incrementally. Diego insists the second annual Atlantic City All Star Boxing Legends Gala will not be the last.

“This really is a labor of love,” he said. “I’ve been a boxing fan since I was a preteen. In the ’70s and ’80s I watched guys like Ray Mancini, Livingstone Bramble, Sugar Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran, Marvin Hagler, Tommy Hearns. It was a classic era for boxing and fans got to see the best of the best.

“I was there when my uncle David fought James Toney for the middleweight title. He got robbed. All right, he was in trouble in the first and second rounds, but he dominated the rest of the way. He was the far busier and more effective fighter. That fight inspired me to become more involved in the sport.

“I remember when Uncle David used to hold his `Night of Champions’ in Wilmington, Delaware. He had guys like Smokin’ Joe Frazier come in. I went to a couple of those events and thought, `Why can’t we do something like that in Atlantic City, only bigger and better?’ And this is bigger and better. It’s going to keep getting bigger and better.”

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThomas Hauser’s Literary Notes: Johnny Greaves Tells a Sad Tale

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRolly Romero Upsets Ryan Garcia in the Finale of a Times Square Tripleheader

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

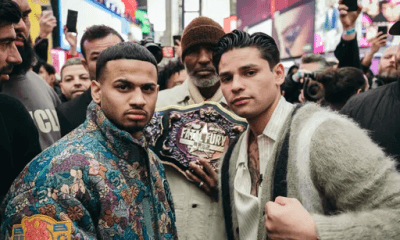

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 324: Ryan Garcia Leads Three Days in May Battles

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoUndercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More