Featured Articles

Who’s Really ‘The Greatest’ Heavyweight Champion Ever?

Boxing writers like to make lists. It’s sort of what we do. I suppose it’s been officially that way ever since promoter Tex Rickard and publisher Nat Fleisher devised the original Ring Magazine ratings policy back in the 1920s, but it was likely a part of boxing long before that. I can picture fans of the old-time, pioneer pugilists listing and rating the great champions of their day, too, if not with the written word then at least with each other in heated barroom debates.

To me, there is no more intriguing debate in the genre than the ranking of all-time great heavyweight champions. In fact, I’ve spent an embarrassing amount of time in my life thinking about the topic. There is so much to consider on the subject, and it seems as if every boxing historian in the world has given his or her two cents on the matter to boot.

Still, there seems to be a good enough consensus across the board to say there are really only a handful of legitimate contenders for the high honor of laying claim to the very top spot: the greatest.

Here’s a little bit of information on each fighter to help you decide who you think should get the nod. I’ve listed them below in chronological order: the five definitive fighters of the heavyweight division.

Jack Johnson

“The Galveston Giant” was heavyweight boxing’s first great defensive fighter. He was a master of slips, parries, arm blocks and jams, and his ring generalship was said to be without equal. Johnson was the first black heavyweight champion. He defeated Tommy Burns in 1908 and held the title until he lost to giant slugger Jess Willard in 1915. Johnson later claimed to have thrown the fight at the behest of his promoters, but there’s never been a definitive call on the matter. Jack Dempsey called Johnson, “the greatest catcher of punches that ever lived…he could fight all night. He was a combination of Jim Corbett and [Joe] Louis. I’m glad I didn’t have to fight him.”

Ring Magazine founder and longtime editor Nat Fleisher considered Johnson the best heavyweight he ever saw, which included other men on this list like Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis and a young Muhammad Ali.

Jack Dempsey

Dempsey was the roughest sort of hobo you could imagine. He made his way around the world by train long before he hit it big as a prizefighter, but not like those highfalutin hobos who rode inside the cars. No, Jack Dempsey rode the rails by snagging a ride beneath the train, laying himself atop thin metal bars between the undercarriage of the carts and the train track, between life and death.

When a man such as this gets to town, he heads to the only place he can: a bar. There, Dempsey would make himself a few dollars by fighting anyone and everyone who cared to tussle that night. In short, Jack Dempsey was a badass.

Dempsey was an offensive juggernaut. He had punishing power in both hands, and he used them with ferocious intent. He won the heavyweight championship in 1919 by brutalizing the giant Jess Willard over three one-sided rounds in a fight that was over almost as soon as it started. Right before the bout was set to begin, Dempsey learned he had a substantial amount of money to gain if he knocked Willard out in the first round because of a side bet his manager, Jack Kearns, made on his behalf. What followed was perhaps the most brutal, one-sided, first round beatdown in boxing history. Despite it, Dempsey lost the bet. Willard was saved by the bell, and after some confusion that lead Jack to believe he had already won the fight, was remarkably deemed okay to continue by Referee Ollie Pecord. Dempsey had to come back to the ring, and then he finished the big lug off in round three.

Dempsey held the title for almost seven years, fighting sparingly, until he was bested by careful technician Gene Tunney, who had made it his life’s missions to defeat the Great Jack Dempsey, and then did so.

Boxing writer Ted Carroll said Dempsey “possessed the natural gifts of unusual quickness, inborn savagery, ruggedness and punching power…his attack was tigerlike [sic] in its intensity.” It’s no wonder, then, that fans dubbed him the “Manassas Mauler.”

Rocky Marciano

For being the only man on this list to retire unbeaten, Rocky Marciano seems to be consistently underrated by most historians today. The “Brockton Blockbuster” was as tough as they come. He’d come forward, slipping and catching as many punches as he could until he put himself in position to land his devastatingly hard punches.

The Rock won the heavyweight crown in 1952 by defeating Jersey Joe Walcott in classic fashion. Walcott dropped Marciano in the first round, then steadily built a point advantage until he got knocked out in round thirteen round by Marciano’s signature “Suzie Q” overhand right. Marciano held the title until he retired in 1955, besting hall-of-famers Ezzard Charles and Archie Moore along the way.

Perhaps Marciano’s greatest attribute was simply his grit and determination. Our own Springs Toledo notes Marciano would be “unlikely to ever lose a test of wills” and that “he seemed to get stronger as fights wore on and opponents wore out.”

And Marciano wore all of them out. All of them.

Joe Louis

Truth be told, I happen to be of the opinion that God made one perfect heavyweight prizefighter, and that it was Joe Louis. It’s a sentiment shared by many notable boxing historians, though the bulk of the balance might lean towards Muhammad Ali.

“The Brown Bomber” put together the most impressive championship reign in the history of the sport. He kept the heavyweight crown on his head for almost 12 years, defending it a record 25 times before he retired. He was a remarkable 58-1 at the time, having avenged his only loss (Max Schmeling) by first round knockout. It was a picture perfect display of his unparalleled power, speed and technical precision. Louis was devastatingly accurate and wielded beautifully mechanical combination punches with frightening ease. He wasn’t just a monster in the ring. Louis was a machine.

In 2003, Ring Magazine praised him as the greatest puncher of all-time. Our resident historical expert, Frank Lotierzo, calls Louis “the most faultless heavyweight fighter in history.” Moreover the International Boxing Research Organization ranks Louis the top heavyweight in history according to its most recently updated member poll in 2006.

Boxing.com’s Matt McGrain hails Louis “as capable a combination puncher as ever lived, his hands were lightning, devastatingly accurate, he punched with huge power and maximum economy…who could force the attack with horrifying results.”

Muhammad Ali

Many ring historians consider Muhammad Ali one of the top heavyweight champions ever, most often being placed in either the first or second position. Ring Magazine ranked him number one among all-time heavyweight champions in 1998, while the International Boxing Research Organization ranked him second under the same criteria in 2006.

While the weight of certain criteria may be debatable, less so is the stature of his resume in the sports’ grandest division. There is simply no heavyweight champion in history that defeated as many top contenders and fellow all-time greats as Ali.

Ali was tall for a heavyweight, but he patterned his style after the little guys. His “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” tactic mesmerized his opponents when he was young. He’d pop his pristine jab to their jaws and follow it up with hard right crosses almost at will, all the while avoiding a return with his tremendously fast feet.

When Ali slowed down a bit in the later years, he showed he had an all-time great chin to go along with his already impressive repertoire. His three encounters with Joe Frazier, in which he went 2-1, included moments that were some of the best in boxing history. His 1974 upset of the previously undefeated George Foreman ranks among the greatest upsets in boxing history, and he’s the only man to win the lineal heavyweight championship three times.

Through Ali’s title reigns, 1964-1970, 1974-1978 and 1978-1979, he amassed a total of 19 successful title defenses.

The Other Guys

Other men may have claim for consideration, too, but none quite make the grade completely. Sticking to chronological order, James J. Jeffries comes to mind. He was probably the biggest and the best of the old-timers, and he retired undefeated before foolishly trying his hand against Jack Johnson over five years and fifty pounds later. George Foreman and Joe Frazier were great, but neither solidified himself as the best of his era. To that end, wherever you come out on the Mike Tyson, Evander Holyfield and Lennox Lewis debate, you might think that person has a shot at the list. But the fact that it’s a lively debate at all leaves enough mystery to leave all of them out. Finally, Wladimir Klitschko may be on his way there someday, but his career still has a ways to go and finding top notch competition will remain tough as ever.

So who’s really the greatest heavyweight champion of all-time?

That’s for you to decide, TSS readers. Tell us who you think is really ‘The Greatest’ heavyweight champion ever. Leave a comment in our forum, or tweet us at @TSSBoxingNews using the hashtag #Greatest. Is there someone else that should be on this list? Is there someone here that doesn’t belong? Let us know!

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

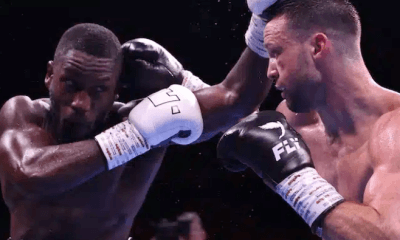

Featured Articles3 weeks agoEkow Essuman Upsets Josh Taylor and Moses Itauma Blasts Out Mike Balogun in Glasgow

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNewspaperman/Playwright/Author Bobby Cassidy Jr Commemorates His Fighting Father

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoSam Goodman and Eccentric Harry Garside Score Wins on a Wednesday Card in Sydney

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 326: A Hectic Boxing Week in L.A.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoHiruta, Bohachuk, and Trinidad Win at the Commerce Casino

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDavid Allen Bursts Johnny Fisher’s Bubble at the Copper Box