Featured Articles

Battle Hymn – Part 5: Blind Tiger

Until the middle of World War II, San Francisco was among the most integrated cities in the United States. Unlike Chicago and other big cities, there were no ghettoes; no plans to stack black people on top of each other to keep them at a distance and conserve space. Sociologists believe this was because they had not yet arrived en masse to threaten the status quo.

Aaron Wade was one of thousands of single African American men trickling into San Francisco before World War II. He and they mixed in with other groups emigrating from outside the United States to create a truly cosmopolitan city where cultural traits from cuisine to speech patterns were regularly exchanged. This was especially so in the Fillmore section of the city: “Day or night,” said the WPA’s guide to the city in 1940, “pass laughing Negroes, dapper Filipino boys, pious old Jews on their way to schule, sturdy-legged Japanese high school girls, husky American longshoremen out for a quiet stroll with the wife and kids.”

This idyllic multiculturalism was put to the wind like pixie dust after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941. To the dismay of many then and now, President Franklin Roosevelt proved to be no friend to Japanese citizens. He signed an executive order authorizing the physical removal of all of them from the West Coast. Signs were posted around San Francisco setting the deadline for April 7. On the foggy morning of April 8, the area between Geary and Pine Streets known as “Little Osaka” and “Japantown” looked like the Rapture. Japanese businesses were boarded up and empty houses loomed on empty streets. The residents were bussed to “war relocation centers” in Topaz, Utah.

In 1940, Wade was one of only 4,846 African Americans living in San Francisco. After Roosevelt gave Japanese Americans the federal boot, throngs in the old slave states packed their things and headed west. They were encouraged by a surplus of freed-up real estate and the bright prospect of finding work in wartime industry. By 1950 there were 43,460 blacks in the city, an increase of nearly 800%.

Wade was still renting his room on McAllister Street in the Fillmore in the early forties. Then known as “second-hand row,” McAllister Street was “spicy with the odors of delicatessen shops, bakeries, and restaurants,” according to the WPA, and merchants and customers parleyed in any number of languages all day. It was “a gourmet’s paradise” which proved to be one reason why the Little Tiger got “roly-poly.” He married Gertrude “Jenny” Johnson and a son, Harvey Dexter Wade, was born in September. Wade soon moved his new family into larger quarters a few blocks closer to Fillmore Street. He should have went in the other direction. Fillmore Street was where the action was —and where a family man shouldn’t be.

When the sun went down, old gospel songs would drift out of church windows and Wade, passing merrily by, might have had his conscience poked. But probably not. Despite the fact that he was only two generations removed from slavery, he hadn’t a care in the world or concern about the next. He was headed toward the entertainment scene, where Jazz Clubs like Jimbo’s Bop City had jam sessions that lasted into the wee hours and featured guests like Count Basie and Ella Fitzgerald. His hang-outs were creep joints that catered to carousers with too much time on their hands and no reason to get up early.

It wasn’t always fun.

A little before midnight on December 26, 1943, a gunshot sent patrons at an all-night café on Fillmore Street scrambling for the door. Wade stepped out of a booth gripping his left shoulder, which was bleeding. Jack Chase had shot him. The police arrived to the café to find Chase swearing it was accidental; he said his gun discharged when he reached into his coat for cigarettes. His live-in girlfriend and Wade both supported the story, but Chase was arrested and held at city prison for assault with intent to commit murder, possession of a deadly weapon, and filing the serial numbers off his .32 caliber pistol. Wade went to the hospital.

Six months later the two drinking buddies were in opposite corners of an Oakland ring. “Chase elected to stand and slug it out with Wade for eight rounds,” said the Oakland Tribune. “It was a mistake.” He was thrashed like a rag doll until the last round when he landed a punch to Wade’s eye and Wade, temporarily blinded, twisted and began pawing at it. Surrender came in the last round. The ringside physician later said that his optic nerve had been paralyzed. Chase had either landed a lucky punch or “heeled” him, that is, rubbed the laces of his glove on Wade’s eyes. Wade’s sight returned after a little while, though the damage proved permanent.

Chase did not emerge unscathed; Muller said he “wasn’t right” for weeks afterward. Chase seldom said much about his opponents, but Wade’s power astonished him. He would say that no one ever hit him harder. “That boy can really punch,” Chase said. “No one can take chances with him. If they do, they may regret it.”

Wade found himself neck-deep in Murderers’ Row over the next four months. He broke even; but before anyone would think his partying days were over, he took his purse money and opened a night club. Located at 1640 Post Street, the “Gay Paree” was on the site of the now-vacant Fuji Transfer Company and featured an orchestra and plenty of booze. It opened in October 1944—on Friday the 13th. Three days later it was raided by the police for operating without a liquor license. Wade appeared in court and paid a fine; then the real trouble began.

Word on the street said that gamblers had been approaching main event fighters with bribes to fix fights. Wade was subpoenaed.

On April 11, 1945, he appeared before the grand jury to testify about what he knew. The following day he showed up at the district attorney’s office unannounced. It wasn’t the first time.

District Attorney Edmund “Pat” Brown had an office at the Hall of Justice on Kearney Street. Alan Wade told me that Brown was a boxing fan who went to the fights at the Winterland and the Bucket of Blood and had a soft spot for the Little Tiger. When Wade ran out of money, which was often, he would head over to Brown’s office for a loan. Eventually, Brown had to shut him off for nonpayment.

When Wade showed up at Brown’s office on April 12, it wasn’t for a handout. He had a proposition that was, said Brown, “the most remarkable one I have received since I have been district attorney.”Wade said that “if the investigation of the crooked fights was dropped,” he would “guarantee there would be no more ‘fixed fights’ on this side of the bay.” Brown turned it down cold and informed the fighter that the investigation would continue. He might have also told him to walk it off.

“He was always a drinker, but it got worse around mid-career,” Alan told me. He’d go on binges, sometimes when he should have been training. In a sport that attracted gamblers with bank rolls and every other kind of shark and hustler—in a racket where you had to be sharp to protect your money, reputation, and future, Wade’s judgment was regularly impaired. Given that he had a family to support, co-owned a club that was springing leaks, and had a tough time getting enough fights to support his night life, he was an easy mark to begin with. Whether Wade was directly involved in fixing fights is unknown. Was his proposition to the district attorney made on behalf of a third party? Was it a booze-induced delusion? The record is as hazy as the fighter on a Saturday night.

We know that others beside him were summoned to appear before the grand jury. One witness, also a boxer, admitted that he had received threatening phone calls. “They tell me I had better get out of town,” he said under oath, “or change my testimony.” A main-eventer like Wade certainly knew what was going on behind the scenes. He also knew the risks of singing about it. When he testified under oath, he said nothing worth reporting, but then he went to Brown’s office and said too much. When it hit the papers, he may have panicked.

On April 17, the San Francisco Chronicle reported Wade as “missing from his usual haunts.”

In May, a black trainer and the white owner of the Brown Bomber Dance Hall in the Fillmore District were indicted. Brown had evidence that they had acted on behalf of shadowy figures from Brooklyn who had come to San Francisco to put fights in the bag.

Soon after those indictments were announced, Wade left his family behind and hightailed it east.

Pioneer Urbanites: A Social and Cultural History of Black San Francisco by Douglas Henry Daniels (Univ. of CA Press, 1990), pp. 98-99, 100 and San Francisco in the 1930s: The WPA Guide to The City by the Bay (1940), pp. 282-285;Wade’s build and avoidance issue in San Francisco Examiner 6/29/40 and 6/20/43; Chase-Wade bouts found in San Francisco Chronicle 6/28/44, Los Angeles Times 12/28/43; San Francisco Examiner 12/27/43, 7/1, 4, 18, 19/44; 8/10/44; UP 6/29/44; Gay Paree in San Francisco Examiner, 10/13/44 and 3/3/45; Chase’s warning in Oakland Tribune 10/9/44; Edmund “Pat” Brown’s investigation of fixed fights covered in San Francisco Examiner from March through May 1945; Oakland Tribune, 4/15/45.

Special thanks to Alan Roy Wade.

Springs Toledo can be contacted at scalinatella@hotmail.com .

Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 326: Top Rank and San Diego Smoke

Avila Perspective, Chap. 326: Top Rank and San Diego Smoke

Years ago, I worked at a newsstand in the Beverly Hills area. It was a 24-hour a day version and the people that dropped by were very colorful and unique.

One elderly woman Eva, who bordered on homeless but pridefully wore lipstick, would stop by the newsstand weekly to purchase a pack of menthol cigarettes. On one occasion, she asked if I had ever been to San Diego?

I answered “yes, many times.”

She countered “you need to watch out for San Diego Smoke.”

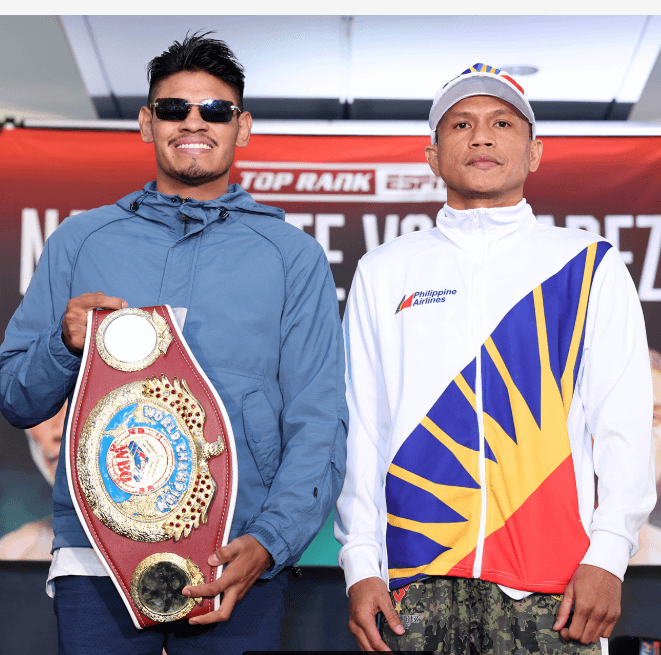

This Saturday, Top Rank brings its brand of prizefighting to San Diego or what could be called San Diego Smoke. Leading the fight card is Mexico’s Emanuel Navarrete (39-2-1, 32 KOs) defending the WBO super feather title against undefeated Filipino Charly Suarez (18-0, 10 KOs) at Pechanga Arena. ESPN will televise.

This is Navarrete’s fourth defense of the super feather title.

The last time Navarrete stepped in the boxing ring he needed six rounds to dismantle the very capable Oscar Valdez in their rematch. One thing about Mexico City’s Navarrete is he always brings “the smoke.”

Also, on the same card is Fontana, California’s Raymond Muratalla (22-0, 17 KOs) vying for the interim IBF lightweight title against Russia’s Zaur Abdullaev (20-1, 12 KOs) on the co-main event.

Abdullaev has only fought once before in the USA and was handily defeated by Devin Haney back in 2019. But that was six years ago and since then he has knocked off various contenders.

Muratalla is a slick fighting lightweight who trains at the Robert Garcia Boxing Academy now in Moreno Valley, Calif. It’s a virtual boot camp with many of the top fighters on the West Coast available to spar on a daily basis. If you need someone bigger or smaller, stronger or faster someone can match those needs.

When you have that kind of preparation available, it’s tough to beat. Still, you have to fight the fight. You never know what can happen inside the prize ring.

Another fighter to watch is Perla Bazaldua, 19, a young and very talented female fighter out of the Los Angeles area. She is trained by Manny Robles who is building a small army of top female fighters.

Bazaldua (1-0, 1 KO) meets Mona Ward (0-1) in a super flyweight match on the preliminary portion of the Top Rank card. Top Rank does not sign many female fighters so you know that they believe in her talent.

Others on the Top Rank card in San Diego include Giovani Santillan, Andres Cortes, Albert Gonzalez, Sebastian Gonzalez and others.

They all will bring a lot of smoke to San Diego.

Probox TV

A strong card led by Erickson “The Hammer” Lubin (26-2, 18 KOs) facing Ardreal Holmes Jr. (17-0, 6 KOs) in a super welterweight clash between southpaws takes place on Saturday at Silver Spurs Arena in Kissimmee, Florida. PROBOX TV will stream the fight card.

Ardreal has rocketed up the standings and now faces veteran Lubin whose only losses came against world titlists Sebastian Fundora and Jermell Charlo. It’s a great match to decide who deserves a world title fight next.

Another juicy match pits Argentina’s Nazarena Romero (14-0-2) against Mexico’s Mayelli Flores (12-1-1) in a female super bantamweight contest.

Nottingham, England

Anthony Cacace (23-1, 8 KOs) defends the IBO super featherweight title against Leigh Wood (28-3, 17 KOs) in Wood’s hometown on Saturday at Nottingham Arena in Nottingham, England. DAZN will stream the Queensberry Promotions card.

Ireland’s Cacace seems to have the odds against him. But he is no stranger to dancing in the enemy’s lair or on foreign territory. He formerly defeated Josh Warrington in London and Joe Cordina in Riyadh in IBO title defenses.

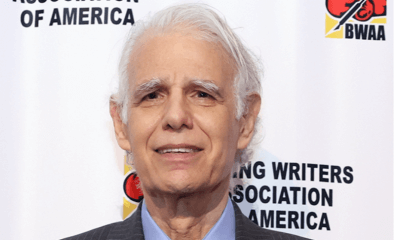

Lampley at Wild Card

Boxing telecaster Jim Lampley will be signing his new book It Happened! at the Wild Card Boxing gym in Hollywood, Calif. on Saturday, May 10, beginning at 2 p.m. Lampley has been a large part of many of the greatest boxing events in the past 40 years. He and Freddie Roach will be at the signing.

Fights to Watch (All times Pacific Time)

Sat. DAZN 11 a.m. Anthony Cacace (23-1) vs Leigh Wood (28-3).

Sat. PROBOX.tv 3 p.m. Erickson Lubin (26-2) vs Ardreal Holmes Jr. (17-0).

Sat. ESPN 7 p.m. Emanuel Navarrete (39-2-1) vs Charly Suarez (18-0); Raymond Muratalla (22-0) vs Zaur Abdullaev (20-1).

Photo credit: Mikey Williams / Top Rank

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

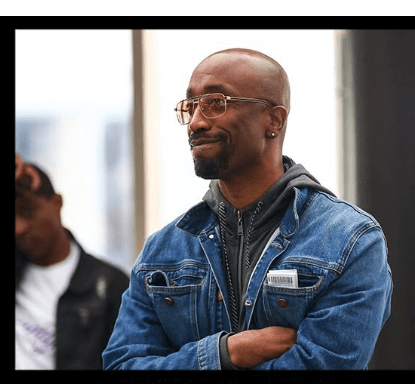

“Breadman” Edwards: An Unlikely Boxing Coach with a Panoramic View of the Sport

Stephen “Breadman” Edwards’ first fighter won a world title. That may be some sort of record.

It’s true. Edwards had never trained a fighter, amateur or pro, before taking on professional novice Julian “J Rock” Williams. On May 11, 2019, Williams wrested the IBF 154-pound world title from Jarrett Hurd. The bout, a lusty skirmish, was in Fairfax, Virginia, near Hurd’s hometown in Maryland, and the previously undefeated Hurd had the crowd in his corner.

In boxing, Stephen Edwards wears two hats. He has a growing reputation as a boxing coach, a hat he will wear on Saturday, May 31, at Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas when the two fighters that he currently trains, super middleweight Caleb Plant and middleweight Kyrone Davis, display their wares on a show that will air on Amazon Prime Video. Plant, who needs no introduction, figures to have little trouble with his foe in a match conceived as an appetizer to a showdown with Jermall Charlo. Davis, coming off his career-best win, an upset of previously undefeated Elijah Garcia, is in tough against fast-rising Cuban prospect Yoenli Hernandez, a former world amateur champion.

Edwards’ other hat is that of a journalist. His byline appears at “Boxing Scene” in a column where he answers questions from readers.

It’s an eclectic bag of questions that Breadman addresses, ranging from his thoughts on an upcoming fight to his thoughts on one of the legendary prizefighters of olden days. Boxing fans, more so than fans of any other sport, enjoy hashing over fantasy fights between great fighters of different eras. Breadman is very good at this, which isn’t to suggest that his opinions are gospel, merely that he always has something provocative to add to the discourse. Like all good historians, he recognizes that the best history is revisionist history.

“Fighters are constantly mislabled,” he says. “Everyone talks about Joe Louis’s right hand. But if you study him you see that his left hook is every bit as good as his right hand and it’s more sneaky in terms of shock value when it lands.”

Stephen “Breadman” Edwards was born and raised in Philadelphia. His father died when he was three. His maternal grandfather, a Korean War veteran, filled the void. The man was a big boxing fan and the two would watch the fights together on the family television.

Edwards’ nickname dates to his early teen years when he was one of the best basketball players in his neighborhood. The derivation is the 1975 movie “Cornbread, Earl and Me,” starring Laurence Fishburne in his big screen debut. Future NBA All-Star Jamaal Wilkes, fresh out of UCLA, plays Cornbread, a standout high school basketball player who is mistakenly murdered by the police.

Coming out of high school, Breadman had to choose between an academic scholarship at Temple or an athletic scholarship at nearby Lincoln University. He chose the former, intending to major in criminal justice, but didn’t stay in college long. What followed were a succession of jobs including a stint as a city bus driver. To stay fit, he took to working out at the James Shuler Memorial Gym where he sparred with some of the regulars, but he never boxed competitively.

Over the years, Philadelphia has harbored some great boxing coaches. Among those of recent vintage, the names George Benton, Bouie Fisher, Nazeem Richardson, and Bozy Ennis come quickly to mind. Breadman names Richardson and West Coast trainer Virgil Hunter as the men that have influenced him the most.

We are all a product of our times, so it’s no surprise that the best decade of boxing, in Breadman’s estimation, was the 1980s. This was the era of the “Four Kings” with Sugar Ray Leonard arguably standing tallest.

Breadman was a big fan of Leonard and of Leonard’s three-time rival Roberto Duran. “I once purchased a DVD that had all of Roberto Duran’s title defenses on it,” says Edwards. “This was a back before the days of YouTube.”

But Edwards’ interest in the sport goes back much deeper than the 1980s. He recently weighed in on the “Pittsburgh Windmill” Harry Greb whose legend has grown in recent years to the point that some have come to place him above Sugar Ray Robinson on the list of the greatest of all time.

“Greb was a great fighter with a terrific resume, of that there is no doubt,” says Breadman, “but there is no video of him and no one alive ever saw him fight, so where does this train of thought come from?”

Edwards notes that in Harry Greb’s heyday, he wasn’t talked about in the papers as the best pound-for-pound fighter in the sport. The boxing writers were partial to Benny Leonard who drew comparisons to the venerated Joe Gans.

Among active fighters, Breadman reserves his highest praise for Terence Crawford. “Body punching is a lost art,” he once wrote. “[Crawford] is a great body puncher who starts his knockouts with body punches, but those punches are so subtle they are not fully appreciated.”

If the opening line holds up, Crawford will enter the ring as the underdog when he opposes Canelo Alvarez in September. Crawford, who will enter the ring a few weeks shy of his 38th birthday, is actually the older fighter, older than Canelo by almost three full years (it doesn’t seem that way since the Mexican redhead has been in the public eye so much longer), and will theoretically be rusty as 13 months will have elapsed since his most recent fight.

Breadman discounts those variables. “Terence is older,” he says, “but has less wear and tear and never looks rusty after a long layoff.” That Crawford will win he has no doubt, an opinion he tweaked after Canelo’s performance against William Scull: “Canelo’s legs are not the same. Bud may even stop him now.”

Edwards has been with Caleb Plant for Plant’s last three fights. Their first collaboration produced a Knockout of the Year candidate. With one ferocious left hook, Plant sent Anthony Dirrell to dreamland. What followed were a 12-round setback to David Benavidez and a ninth-round stoppage of Trevor McCumby.

Breadman keeps a hectic schedule. From Monday through Friday, he’s at the DLX Gym in Las Vegas coaching Caleb Plant and Kyrone Davis. On weekends, he’s back in Philadelphia, checking in on his investment properties and, of greater importance, watching his kids play sports. His 14-year-old daughter and 12-year-old son are standout all-around athletes.

On those long flights, he has plenty of time to turn on his laptop and stream old fights or perhaps work on his next article. That’s assuming he can stay awake.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Arne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

Arne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

It’s old news now, but on back-to-back nights on the first weekend of May, there were three fights that finished in the top six snoozefests ever as measured by punch activity. That’s according to CompuBox which has been around for 40 years.

In Times Square, the boxing match between Devin Haney and Jose Carlos Ramirez had the fifth-fewest number of punches thrown, but the main event, Ryan Garcia vs. Rolly Romero, was even more of a snoozefest, landing in third place on this ignoble list.

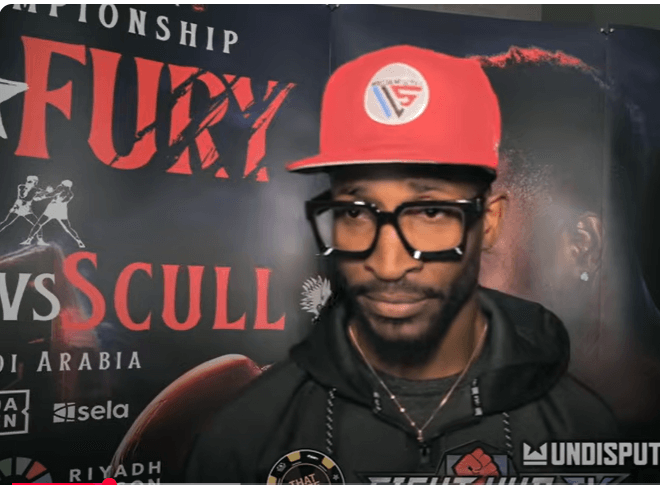

Those standings would be revised the next night – knocked down a peg when Canelo Alvarez and William Scull combined to throw a historically low 445 punches in their match in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 152 by the victorious Canelo who at least pressed the action, unlike Scull (pictured) whose effort reminded this reporter of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” – no, not the movie starring Paul Newman, just the title.

CompuBox numbers, it says here, are best understood as approximations, but no amount of rejiggering can alter the fact that these three fights were stinkers. Making matters worse, these were pay-per-views. If one had bundled the two events, rather than buying each separately, one would have been out $90 bucks.

****

Thankfully, the Sunday card on ESPN from Las Vegas was redemptive. It was just what the sport needed at this moment – entertaining fights to expunge some of the bad odor. In the main go, Naoya Inoue showed why he trails only Shohei Ohtani as the most revered athlete in Japan.

Throughout history, the baby-faced assassin has been a boxing promoter’s dream. It’s no coincidence that down through the ages the most common nickname for a fighter – and by an overwhelming margin — is “Kid.”

And that partly explains Naoya Inoue’s charisma. The guy is 32 years old, but here in America he could pass for 17.

Joey Archer

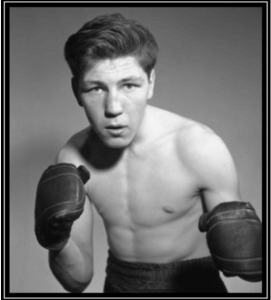

Joey Archer, who passed away last week at age 87 in Rensselaer, New York, was one of the last links to an era of boxing identified with the nationally televised Friday Night Fights at Madison Square Garden.

Joey Archer

Archer made his debut as an MSG headliner on Feb. 4, 1961, and had 12 more fights at the iconic mid-Manhattan sock palace over the next six years. The final two were world title fights with defending middleweight champion Emile Griffith.

Archer etched his name in the history books in November of 1965 in Pittsburgh where he won a comfortable 10-round decision over Sugar Ray Robinson, sending the greatest fighter of all time into retirement. (At age 45, Robinson was then far past his peak.)

Born and raised in the Bronx, Joey Archer was a cutie; a clever counter-puncher recognized for his defense and ultimately for his granite chin. His style was embedded in his DNA and reinforced by his mentors.

Early in his career, Archer was domiciled in Houston where he was handled by veteran trainer Bill Gore who was then working with world lightweight champion Joe Brown. Gore would ride into the Hall of Fame on the coattails of his most famous fighter, “Will-o’-the Wisp” Willie Pep. If Joey Archer had any thoughts of becoming a banger, Bill Gore would have disabused him of that notion.

In all honesty, Archer’s style would have been box office poison if he had been black. It helped immensely that he was a native New Yorker of Irish stock, albeit the Irish angle didn’t have as much pull as it had several decades earlier. But that observation may not be fair to Archer who was bypassed twice for world title fights after upsetting Hurricane Carter and Dick Tiger.

When he finally caught up with Emile Griffith, the former hat maker wasn’t quite the fighter he had been a few years earlier but Griffith, a two-time Fighter of the Year by The Ring magazine and the BWAA and a future first ballot Hall of Famer, was still a hard nut to crack.

Archer went 30 rounds with Griffith, losing two relatively tight decisions and then, although not quite 30 years old, called it quits. He finished 45-4 with 8 KOs and was reportedly never knocked down, yet alone stopped, while answering the bell for 365 rounds. In retirement, he ran two popular taverns with his older brother Jimmy Archer, a former boxer who was Joey’s trainer and manager late in Joey’s career.

May he rest in peace.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoJaron ‘Boots’ Ennis Wins Welterweight Showdown in Atlantic City

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective Chap 320: Boots Ennis and Stanionis

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDzmitry Asanau Flummoxes Francesco Patera on a Ho-Hum Card in Montreal

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMekhrubon Sanginov, whose Heroism Nearly Proved Fatal, Returns on Saturday

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 322: Super Welterweight Week in SoCal

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTSS Salutes Thomas Hauser and his Bernie Award Cohorts

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoGabriela Fundora KOs Marilyn Badillo and Perez Upsets Conwell in Oceanside