Featured Articles

Battle Hymn – Part 7: Sugar On The Sidewalk

Chuck Burroughs’ sixty years in the Peoria, Illinois boxing scene began in the crowded backseat of Jack Beaty’s reo. A Golden Gloves champion who later became a referee, ring announcer, corner man, journalist, author, and local historian, Burroughs kept tabs on his old teammates long after their fighting days ended. When he died, several of his scrapbooks were donated to the Peoria Public Library. I tracked them down, hoping to unearth more about the Little Tiger. Burroughs didn’t disappoint.

He had chronicled Peoria’s Golden Gloves history and devoted a long paragraph to “Peoria’s first Negro Golden Glove Champ” Aaron Wade. There is a curious scrap of information midway through it that says Wade was “chief sparring partner for Sugar Ray when he was welterweight champ.” Robinson, of course, was a Harlemite. I knew Wade had been living in New York since 1945. After the embarrassing loss to Wylie Burns in 1947, Wade had no income and one marketable skill; Burroughs’ detail shines a light on where he wandered off to after that loss.

Robinson was scheduled to face Steve Belloise on December 9, 1948. His workouts were held at the Uptown Gymnasium at 252 W. 116th Street and Wade was a sparring partner. On the morning of the fight, national newspapers announced that the bout was cancelled “due to an injury Robinson is reported to have suffered in training.” The write-ups were heavy on details, but neither the Belloise camp nor the boxing beat was buying it.

Already lauded as perhaps “the greatest boxer in history,” Robinson was also despised by many insiders for what they saw as imperiousness. He had a history of mistreating sparring partners. He ran out on contracts. He postponed bouts. The Belloise bout had already been postponed from its original date and ticket sales were lagging when Robinson’s injury was announced. The event, said the New York Herald-Tribune, cost $40,000 though “less than $15,000 was in the till.” It was suspicious enough to force a public explanation from the champion: “It happened in the last minute of my three-round workout with Tiger Wade here on Monday,” Robinson said. “Wade’s a 170-pounder. He hit me with a right uppercut down here. I felt like he stabbed me with a knife.”

Doctors were marched out to reassure a doubting press that Robinson had indeed suffered a separation between the sixth and seventh ribs. Reporters were invited to feel the egg-sized lump under his heart for further proof. Many did, and the fact of his injury had to be accepted. Given the fact that the sparring partner who did it was a once-feared puncher, Robinson’s explanation of how he was injured was likewise accepted.

But Robinson was lying.

Two years ago, boxing historian J.J. Johnston told me about a rumor he had heard. The rumor said that the Little Tiger had once knocked down Robinson outside of a Boston gym. I spent weeks sifting for more leads only to find that the past had pulled the shade. I filed the rumor away. About a month ago I was flipping through pages of Burroughs’ Peoria scrapbook and my eyes darted to a glittering sentence: “Whipped Sugar Ray in a street fight over some money Sugar owed him.” Now that’s independent corroboration, which makes a rumor more than a rumor. However, it still wasn’t enough to justify publishing it—Robinson’s name is like thunder in the boxing world, even today. I needed confirmation, and found it on microfilm at the Boston Public Library.

The Boston Post folded in 1956. Its circulation was in a free-fall in the forties, though it still had at least one shoe-leather reporter in Gerry Hern. As news of Robinson’s so-called sparring injury and the fight cancellation hit the stands, Hern was turning up primary sources. One of them was unnamed but was almost certainly Little Tiger Wade, and Wade had a tale to tell.

“There was nothing accidental about Robinson’s rib separation,” Hern revealed in an article published Friday, December 10,1948. “It was the result of trying to shave the overhead a little bit, his own personal overhead, for the fight.” Here’s what happened: Robinson and Wade sparred the previous Tuesday at the Uptown Gymnasium. Robinson, feeling the pinch of the lagging ticket sales for his fight Thursday, told Wade that he would have to accept less money than promised. Wade objected at first, then relented. “What can I do about it,” he said. “You’re the boss. I’ve got to take it.”

Wade left the gym, but changed his mind and waited for the champion on the sidewalk. When Robinson came out, Wade confronted him. “I want all the dough or none,” he said. “I’m just a punk in this business but I want my money.” Robinson, said Hern, starting telling “his broken-down sparring partner that he would be lucky to get anything—but he didn’t finish. Wade fired his Sunday punch that knocked Robinson to the sidewalk and then gave him a brisk going-over.”

The spectacle of a member of Murderers’ Row finally closing the distance on Robinson and punishing him is startling. Is it poetic justice? Robinson later wrote an article for Ebony magazine defending his business acumen. “A broke fighter is a pitiful sight,” he said. “I’ve seen too many of them not to have learned a lesson or two. Great boxing skill is no sure guarantee that a fighter won’t end up hungry and raggedy. Most fighters end up broke.” Then he offered a little advice. “A fighter these days must express himself, must speak up when he thinks he’s being shoved around.”

It could be said that Wade ‘expressed himself’ on behalf of many; on behalf of many on Murderers’ Row.

The pair would have another ill-fated encounter in February 1950. Robinson was scheduled for a main event in Savannah, Georgia, when his scheduled opponent got shot in New Orleans. The local promoter, Buster White, was desperate to find a substitute; a black substitute, to be precise, because southern law prohibited fair fights between the races. Robinson’s manager remembered that Aaron Wade always needed a buck. For all intents and purposes, Wade had been retired for 793 days; he needed a few bucks.

The doors to the Municipal Auditorium opened at 8:30pm on February 15. “Ladies and gentleman, tonight you will see one of the greatest champions of all time,” the program said. “Robinson could easily become a triple champion if given the opportunity to fight for the middleweight and light-heavyweight titles.” Two thousand black and white citizens streamed in by separate entrances. The blacks were seated in the balcony, the whites around the ring. During the main event, they were booing together.

“Ray battered his stocky, keg-like foe savagely,” said the Savannah Morning News. “Mostly he put on a beautiful combination of foot-work and body weaving which left the Tiger shadow boxing.” Robinson’s “favorite stunt” was to grab the rope with his right glove and leave his left free to “tantalize and punish Wade by smearing that hand all over the Tiger’s face and body.” It was an artistic display. It seemed a little too artistic. Wade fell five times in the second round. The first time seemed more like a slip. The second time saw him “dumped on his rear end through the ropes.” The third time Wade went down, “it looked for certain that the glove missed Wade’s face altogether and caught him in the shoulder instead. At any rate, he went down again.”

The crowd was wild between the second and third round, more “at Wade’s taste for canvas than in appreciation for Ray’s aptitude.” Before the bell, Robinson stood up and gestured that he would bring the fiasco to a conclusion. When the third round began, he set out to do so and, reads the article, “Wade seemed willing to cooperate.”

The Savannah Evening Press was also suspicious. “The Tiger—let’s call him Aaron—,” it said, “began hitting the canvas for apparently no reason at all. As Robinson moved within firing range the husky Wade repeatedly fell to the canvas.” Waldo Spence, sports editor for the Press, got right to the point: “Robinson never during the evening hit Wade with a solid punch.”

Years later, Wade privately confirmed what many thought they saw that night. He told his son he had taken a dive. When Alan told me, a shadow crossed my mind. I had to ask “—did Robinson know?” It turns out that he had asked his father that very question. His father shook his head. “Robinson had nothing to do with it.”

“Who approached your father?” I asked Alan. “It was the promoters,” he said. “They told him to go down in three rounds for a few hundred dollars.”

Alan had one other detail he could recall. Wade, he said, had asked the promoters if he could go “five or six rounds.” It was, I suppose, an attempt to salvage whatever scrap of pride he had left. But they turned him down. “Three,” they said.

I found it a little sad.

“WhyI’m the Bad Boy of Boxing,” by Sugar Ray Robinson (Ebony, November 1950); Savannah Morning News 2/22, 23/50; New York Times 2/23/50; Savannah Evening Press, 2/23/1950; Behind the Moss Curtain by Murray Silver (2002), pp. 238-239.

Special thanks to J.J. Johnston.

Springs Toledo can be contacted at scalinatella@hotmail.com .

Featured Articles

Arne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

Arne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

It’s old news now, but on back-to-back nights on the first weekend of May, there were three fights that finished in the top six snoozefests ever as measured by punch activity. That’s according to CompuBox which has been around for 40 years.

In Times Square, the boxing match between Devin Haney and Jose Carlos Ramirez had the fifth-fewest number of punches thrown, but the main event, Ryan Garcia vs. Rolly Romero, was even more of a snoozefest, landing in third place on this ignoble list.

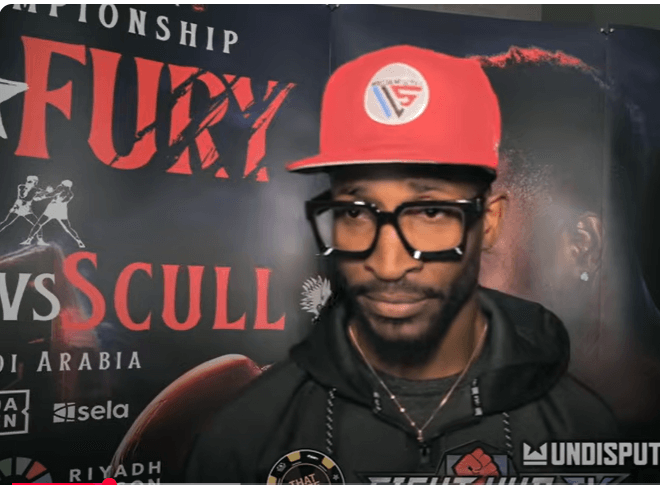

Those standings would be revised the next night – knocked down a peg when Canelo Alvarez and William Scull combined to throw a historically low 445 punches in their match in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 152 by the victorious Canelo who at least pressed the action, unlike Scull (pictured) whose effort reminded this reporter of “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” – no, not the movie starring Paul Newman, just the title.

CompuBox numbers, it says here, are best understood as approximations, but no amount of rejiggering can alter the fact that these three fights were stinkers. Making matters worse, these were pay-per-views. If one had bundled the two events, rather than buying each separately, one would have been out $90 bucks.

****

Thankfully, the Sunday card on ESPN from Las Vegas was redemptive. It was just what the sport needed at this moment – entertaining fights to expunge some of the bad odor. In the main go, Naoya Inoue showed why he trails only Shohei Ohtani as the most revered athlete in Japan.

Throughout history, the baby-faced assassin has been a boxing promoter’s dream. It’s no coincidence that down through the ages the most common nickname for a fighter – and by an overwhelming margin — is “Kid.”

And that partly explains Naoya Inoue’s charisma. The guy is 32 years old, but here in America he could pass for 17.

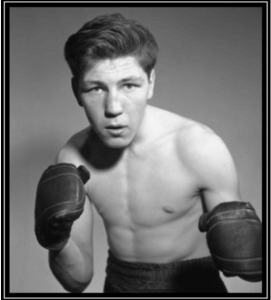

Joey Archer

Joey Archer, who passed away last week at age 87 in Rensselaer, New York, was one of the last links to an era of boxing identified with the nationally televised Friday Night Fights at Madison Square Garden.

Joey Archer

Archer made his debut as an MSG headliner on Feb. 4, 1961, and had 12 more fights at the iconic mid-Manhattan sock palace over the next six years. The final two were world title fights with defending middleweight champion Emile Griffith.

Archer etched his name in the history books in November of 1965 in Pittsburgh where he won a comfortable 10-round decision over Sugar Ray Robinson, sending the greatest fighter of all time into retirement. (At age 45, Robinson was then far past his peak.)

Born and raised in the Bronx, Joey Archer was a cutie; a clever counter-puncher recognized for his defense and ultimately for his granite chin. His style was embedded in his DNA and reinforced by his mentors.

Early in his career, Archer was domiciled in Houston where he was handled by veteran trainer Bill Gore who was then working with world lightweight champion Joe Brown. Gore would ride into the Hall of Fame on the coattails of his most famous fighter, “Will-o’-the Wisp” Willie Pep. If Joey Archer had any thoughts of becoming a banger, Bill Gore would have disabused him of that notion.

In all honesty, Archer’s style would have been box office poison if he had been black. It helped immensely that he was a native New Yorker of Irish stock, albeit the Irish angle didn’t have as much pull as it had several decades earlier. But that observation may not be fair to Archer who was bypassed twice for world title fights after upsetting Hurricane Carter and Dick Tiger.

When he finally caught up with Emile Griffith, the former hat maker wasn’t quite the fighter he had been a few years earlier but Griffith, a two-time Fighter of the Year by The Ring magazine and the BWAA and a future first ballot Hall of Famer, was still a hard nut to crack.

Archer went 30 rounds with Griffith, losing two relatively tight decisions and then, although not quite 30 years old, called it quits. He finished 45-4 with 8 KOs and was reportedly never knocked down, yet alone stopped, while answering the bell for 365 rounds. In retirement, he ran two popular taverns with his older brother Jimmy Archer, a former boxer who was Joey’s trainer and manager late in Joey’s career.

May he rest in peace.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Bombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs

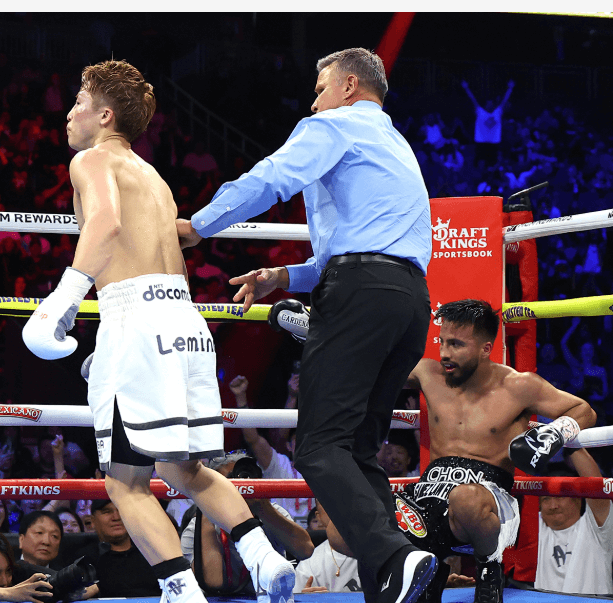

Japan’s Naoya “Monster” Inoue banged it out with Mexico’s Ramon Cardenas, survived an early knockdown and pounded out a stoppage win to retain the undisputed super bantamweight world championship on Sunday.

Japan and Mexico delivered for boxing fans again after American stars failed in back-to-back days.

“By watching tonight’s fight, everyone is well aware that I like to brawl,” Inoue said.

Inoue (30-0, 27 KOs), and Cardenas (26-2, 14 KOs) and his wicked left hook, showed the world and 8,474 fans at T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas that prizefighting is about punching, not running.

After massive exposure for three days of fights that began in New York City, then moved to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and then to Nevada, it was the casino capital of the world that delivered what most boxing fans appreciate- pure unadulterated action fights.

Monster Inoue immediately went to work as soon as the opening bell rang with a consistent attack on Cardenas, who very few people knew anything about.

One thing promised by Cardenas’ trainer Joel Diaz was that his fighter “can crack.”

Cardenas proved his trainer’s words truthful when he caught Inoue after a short violent exchange with a short left hook and down went the Japanese champion on his back. The crowd was shocked to its toes.

“I was very surprised,” said Inoue about getting dropped. ““In the first round, I felt I had good distance. It got loose in the second round. From then on, I made sure to not take that punch again.”

Inoue had no trouble getting up, but he did have trouble avoiding some of Cardenas massive blows delivered with evil intentions. Though Inoue did not go down again, a look of total astonishment blanketed his face.

A real fight was happening.

Cardenas, who resembles actor Andy Garcia, was never overly aggressive but kept that left hook of his cocked and ready to launch whenever he saw the moment. There were many moments against the hyper-aggressive Inoue.

Both fighters pack power and both looked to find the right moment. But after Inoue was knocked down by the left hook counter, he discovered a way to eliminate that weapon from Cardenas. Still, the Texas-based fighter had a strong right too.

In the sixth round Inoue opened up with one of his lightning combinations responsible for 10 consecutive knockout wins. Cardenas backed against the ropes and Inoue blasted away with blow after blow. Then suddenly, Cardenas turned Inoue around and had him on the ropes as the Mexican fighter unloaded nasty combinations to the body and head. Fans roared their approval.

“I dreamed about fighting in front of thousands of people in Las Vegas,” said Cardenas. “So, I came to give everything.”

Inoue looked a little surprised and had a slight Mona Lisa grin across his face. In the seventh round, the Japanese four-division world champion seemed ready to attack again full force and launched into the round guns blazing. Cardenas tried to catch Inoue again with counter left hooks but Inoue’s combos rained like deadly hail. Four consecutive rights by Inoue blasted Cardenas almost through the ropes. The referee Tom Taylor ruled it a knockdown. Cardenas beat the count and survived the round.

In the eighth round Inoue looked eager to attack and at the bell launched across the ring and unloaded more blows on Cardenas. A barrage of 14 unanswered blows forced the referee to stop the fight at 45 seconds of round eight for a technical knockout win.

“I knew he was tough,” said Inoue. “Boxing is not that easy.”

Espinoza Wins

WBO featherweight titlist Rafael Espinosa (27-0, 23 KOs) uppercut his way to a knockout win over Edward Vazquez (17-3, 4 KOs) in the seventh round.

“I wanted to fight a game fighter to show what I am capable,” said Espinoza.

Espinosa used the leverage of his six-foot, one-inch height to slice uppercuts under the guard of Vazquez. And when the tall Mexican from Guadalajara targeted the body, it was then that the Texas fighter began to wilt. But he never surrendered.

Though he connected against Espinoza in every round, he was not able to slow down the taller fighter and that allowed the Mexican fighter to unleash a 10-punch barrage including four consecutive uppercuts. The referee stopped the fight at 1:47 of the seventh round.

It was Espinoza’s third title defense.

Photo credit: Mikey Williams / Top Rank

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

Featured Articles

Undercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

The curtain was drawn on a busy boxing weekend tonight at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas where the featured attraction was Japanese superstar Naoya Inoue appearing in his twenty-fifth world title fight.

The top two fights (Inoue vs. Roman Cardenas for the unified 122-pound crown and Rafael Espinoza vs. Edward Vazquez for the WBO world featherweight diadem) aired on the main ESPN platform with the preliminaries streaming on ESPN+.

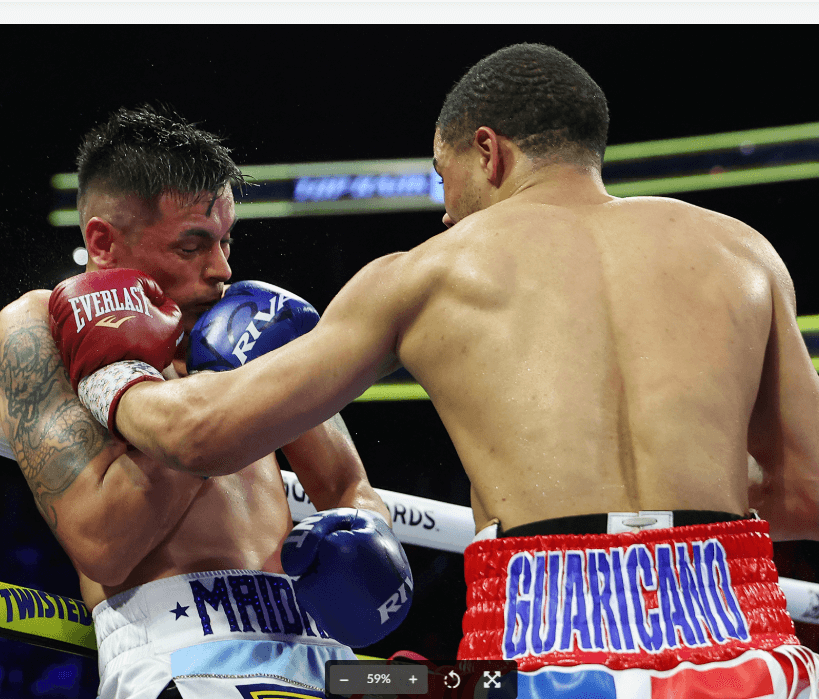

The finale of the preliminaries was a 10-rounder between welterweights Rohan Polanco and Fabian Maidana. A 2020/21 Olympian for the Dominican Republic, Polanco was a solid favorite and showed why by pitching a shutout, punctuating his triumph by knocking Maidana to his knees late in the final round with a hard punch to the pit of the stomach.

Polanco improved to 16-0 (10). Argentina’s Maidana, the younger brother of former world title-holder Marcos Maidana, fell to 24-4 while maintaining his distinction of never being stopped.

Emiliano Vargas, a rising force in the 140-pound division with the potential to become a crossover star, advanced to 14-0 (12 KOs) with a second-round stoppage Juan Leon. Vargas, who turned 21 last month, is the son of former U.S. Olympian Fernando Vargas who had big money fights with the likes of Felix Trinidad and Oscar De La Hoya. Emiliano knocked Leon down hard twice in round two – both the result of right-left combinations — before Robert Hoyle waived it off.

A 28-year-old Spaniard, Leon was 11-2-1 heading in.

In his U.S. debut, 29-year-old Japanese southpaw Mikito Nakano (13-0, 12 KOs) turned in an Inoue-like performance with a fourth-round stoppage of Puerto Rico’s Pedro Medina. Nakano, a featherweight, had Medina on the canvas five times before referee Harvey Dock waived it off at the 1:58 mark of round four. The shell-shocked Medina (16-2) came into the contest riding a 15-fight winning streak.

Lynwood, California junior middleweight Art Barrera Jr, a 19-year-old protégé of Robert Garcia, scored a sixth-round stoppage of Chicago’s Juan Carlos Guerra. There were no knockdowns, but the bout had turned sharply in Barrera’s favor when referee Thomas Taylor intervened. The official time was 1:15 of round six.

Barrera improved to 9-0 (7 KOs). The spunky but outclassed Guerra, who upset Nico Ali Walsh in his previous outing, declined to 6-2-1.

In the lid-lifter, a 10-round featherweight affair, Muskegon Michigan’s Ra’eese Aleem improved to 22-1 (12) with a unanimous decision over LA’s hard-trying Rudy Garcia (13-2-1). The judges had it 99-01, 98-92, and 97-93.

Aleem, 34, was making his second start since June of 2023 when he lost a split decision in Australia to Sam Goodman with a date with Naoya Inoue hanging in the balance.

Check back shortly for David Avila’s recaps of the two world title fights.

Photo credit: Mikey Williams / Top Rank

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

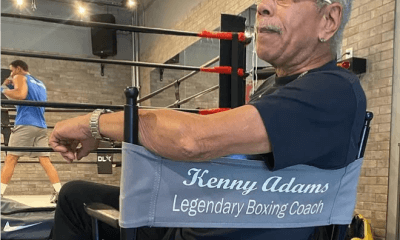

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Hall of Fame Boxing Trainer Kenny Adams

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoJaron ‘Boots’ Ennis Wins Welterweight Showdown in Atlantic City

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective Chap 320: Boots Ennis and Stanionis

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

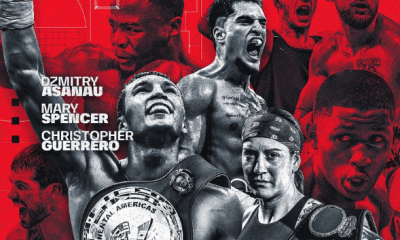

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDzmitry Asanau Flummoxes Francesco Patera on a Ho-Hum Card in Montreal

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMekhrubon Sanginov, whose Heroism Nearly Proved Fatal, Returns on Saturday

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 322: Super Welterweight Week in SoCal

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

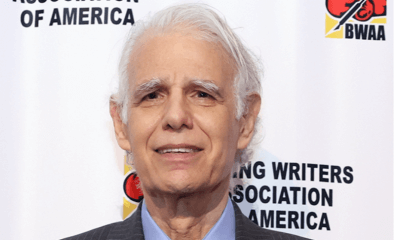

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTSS Salutes Thomas Hauser and his Bernie Award Cohorts