Featured Articles

Just Call New Champ Algieri “Hands of Stony Brook”

NEW YORK – In those 1960s Sergio Leone spaghetti Westerns, opportunistic gunslinger Clint Eastwood played the role of the Man With No Name. Going into Saturday night’s HBO-televised matchup with WBO junior welterweight champion Ruslan Provodnikov at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, Chris Algieri was the Man With No Nickname.

All that might be about to change after Algieri – who has a bachelor’s degree from Stony Brook University and a master’s degree from the New York Institute of Technology – overcame two first-round knockdowns and a rapidly closing right eye to score a major upset over WBO junior welterweight champion Ruslan Provodnikov, on a split decision that might be described as beauty in the one eye of the beholder.

“I knew I was winning each round,” said Algieri, 30, who was a world champion kickboxer before trying his hand, and not his feet, as a boxer in 2008, at the relatively advanced age of 24. “At the end, I really wasn’t too nervous about (the decision). I was just waiting to hear `And new …’”

Algieri got a fistful of dollars, a career-high $100,000, for challenging Provodnikov, and he figures to get quite a few dollars more for his next bout, be it a rematch with the dethroned “Siberian Rocky” or an even more lucrative date with Filipino superstar Manny Pacquiao, the WBO welterweight champion, who is scheduled to make his next title defense on Nov. 22 in Macau, China. Pacquiao’s promoter, Top Rank founder Bob Arum, has said that if Algieri were to defeat Provodnikov, he would get first dibs on the big-bucks, high-visibility gig with Pac-Man. Of course, words said today do not necessarily translate into signed contracts tomorrow. Still, the idea was intriguing to the well-lumped-up Algieri, who admits he switched from kickboxing to boxing because the paydays for those who succeed at the highest levels are significantly higher.

“It would be a great fight,” Algieri, who has a praying-mantis physique for a junior welter at 5-foot-10 and with a 72-inch reach, said of a possible pairing with Pacquiao. “Manny’s definitely a future Hall of Famer. Stylistically, I think it would be a good matchup. He’s another dangerous guy, but I think my style would match up well with his.”

Someone – a fellow Stony Brook alum, the guy noted — mentioned to Algieri that he probably is the first world boxing champion from Stony Brook (whose proper name is the State University of New York at Stony Brook), an academically prestigious institution on the north shore of Long Island. That distinction alone seemingly lends itself to the conferring of the nickname that Algieri previously has been without.

How does “Hands of Stony Brook” grab you?

Truth be told, Algieri’s hands are that of a relatively soft-punching ring tactician and aren’t nearly as hard as his resolve, which had been called into question by any number of skeptics, including Provodnikov, who wondered if an erudite college graduate and aspiring medical doctor from an affluent outer-ring suburb of New York City (Huntington) could withstand the pressure of a relentless, power-hitting champion who came up the way most elite boxers do, from poor and deprived circumstances. Greatness in the cruelest of sports usually is forged in the crucible of desperation, not in upper-middle-class comfort.

“It’s my competitive nature to want fights like this,” said Algieri, who improved to 20-0, with a modest eight victories inside the distance. “And that’s what kept me in this fight. You know, there were a lot of doubters about how much I really wanted it. Ruslan kept talking about how he would die in the ring, if necessary, and would I be willing to do that? But I think I showed that I belonged in there as well.

“I know I didn’t come from a torn, you know, childhood or upbringing. I came from the suburbs of Long Island. I don’t have to fight. I fight because I want to fight. If you didn’t see passion in those 12 rounds, I don’t know what you were looking at.”

Provodnikov (23-3, 16 KOs), who hails from the decidedly non-affluent town of Berezovo, which is in Siberia, the most frozen part of Russia, figures he didn’t deserve the chilly scorecard tabulations he got from judges Tom Schreck, from New York, and Don Trella, from Connecticut, both of whom saw Algieri as the winner by a 114-112 margin. The dissenting judge, Max DeLuca, who is from California, had Provodnikov running away with it to the tune of 117-109.

What it comes down to, as it always does when a bout ends in a disputed decision, is the perspective of three individuals who can be watching the same thing but seeing something entirely different. Punch statistics furnished by CompuBox are a useful tool, but only to a point; they do not account for how damaging those punches are. Therein lies the difference between amateur boxing, where a jab theoretically counts no more than a knockdown shot, and the pros, where quality often factors more into the equation than quantity.

The raw numbers say that Algieri landed 288 of 993 punches thrown, a 29 percent connect rate, to 205 of 776 (26 percent) for Provodnikov. But the pro-Provodnikov side argued that those two first-round knockdowns by the champion, and visual proof of what had happened, in the form of Algieri’s substantially more-damaged face, should have produced a more favorable outcome.

“Power punches win fights,” said Provodnikov’s chief second, the esteemed Freddie Roach, winner of six Trainer of the Year awards from the Boxing Writers Association of America. “(Algieri) outjabbed us, yes. But power punches? It was a thousand to one. We landed the most (effective) shots and that’s why I thought we deserved (to win) the fight.”

Provodnikov, who also earned a career-high purse ($750,000), had hoped that an impressive victory, which he had guaranteed, would vault him into boxing’s exclusive seven-figure club and further cement his burgeoning reputation as an action hero in the mold of a late, great pair of Hall of Famers, Arturo Gatti and Matthew Saad Muhammad. He said he hadn’t come to Brooklyn to enter a track meet or participate in a dance-hall recital.

“I haven’t seen the (replay) to make a judgment on the way it went, but to me it felt like he was running all night and just jabbing,” said Provodnikov. “You can see the way I look and the way he looks. To me, I don’t see how you can win a fight just running all night.

“I start falling asleep when the guy is just running all night. I’m catching him and he’s just running and running. If I started boxing him, you guys (the media) would be falling asleep. I took the fight to him and I made it exciting. I was the only one who made this fight exciting. HBO (commentators) gave, like, nine more rounds to me. One of the judges gave six or seven more rounds to me. The local judges gave it the other way. On top of that, (Algieri’s) eye was closed. It’s dangerous to fight like that. He could have gotten killed. If my eye was like that, they would have stopped the fight in the round that my eye started closing. I think it’s not fair.”

Whether the grumpy Provodnikov truly believes he was the victim of a stickup by pencil, or just perturbed not to have engaged in the sort of toe-to-toe slugfest that more suits his Gattiesque proclivities, only he can say for sure. But there isn’t much doubt he is disdainful of stick-and-move types who won’t engage him in the center of the ring, strength on strength, will against will.

“I said before (Algieri’s) style was not the best style for me,” he complained. “Runners are not my style. He just ran and touched me, just jabbed and touched me. This is the worst style for me. I like guys who are in front of me and fighting me.”

Fortunately for Provodnikov, HBO subscribers and ticket-purchasers like fighters who, as his promoter, Art Pelullo, noted, are “TV-friendly and fan-friendly. Ruslan fights like that all the time. He gets good ratings. I’m sure he’ll get good ratings for this fight. Right now (the HBO suits) are already talking about November or December, so he’ll be back on the network at the end of the year.”

Provodnikov is unquestionably fan-friendly, increasingly so in the United States, but, somewhat interestingly, he was not the rooting choice of the 6,218 spectators who were in the house and much more vocally supportive of Algieri, despite the fact that the Barclays Center is close to Brighton Beach, which is located in the southern portion of Brooklyn and is known for its high population of Russian-speaking immigrants. Every time Provodnikov backers started to chant “Ruslan! Ruslan! Ruslan!,” they were drowned out by louder chants of “Algieri! Algieri! Algieri!” or “USA! USA! USA!” Maybe that old Cold-War thing hasn’t thawed as much as had been supposed.

“I really heard it when I came out,” Algieri said of the support he received. “I heard it when they actually booed Ruslan a little bit, which I’m not happy about. But it did show my numbers were here. Then again, I had said that prior to the fight. People were asking me what the crowd was going to be like. I said it was going to be a pro-Algieri crowd.

“This is how I pictured me winning a world title – having it in New York and fighting like this. But I didn’t picture my face like this.”

No matter what side of the scoring fence anyone falls onto, Algieri deserves credit for displaying a brand of courage real fighters are sometimes asked to reveal. His right eye began to swell in the first round, after he was dropped by that Provodnikov left hook that clearly hurt him, and by fight’s end the hematoma was so massive that the eye was completely closed. It called to mind similar damage done to Carmen Basilio in his 1958 rematch with Sugar Ray Robinson and to Bobby Czyz in his 1987 bout with “Prince” Charles Williams. He did not deserve the shouted declarations of cowardice in Russian that some of Providnokov’s backers directed at him as he scratched back from the deep hole of that 10-7 first round.

In the other HBO-televised bout, which also served as something of a coming-out party, WBO junior middleweight champion Demetrius Andrade (21-0, 14 KOs) completely dominated British challenger Brian Rose (25-2-1, 7 KOs) en route to defending his title on a seventh-round stoppage.

“I’m the best in the world,” Andrade, a southpaw from Providence, R.I., who represented the U.S. at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, said after he did as he pleased against the willing but out-of-his-league Rose. “I was just taking my time. I knew my power was affecting him. I took Round 5 off to see openings. Round 6 I picked it up and in Round 7 he had to go.”

Not unexpectedly, Andrade spent his time at the microphone at the postfight press conference to call out Floyd Mayweather Jr., Canelo Alvarez and Miguel Cotto.

“I couldn’t keep him off me,” said Rose. “He’s better than I thought he would be. He may be one of the best out there in the game today.”

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

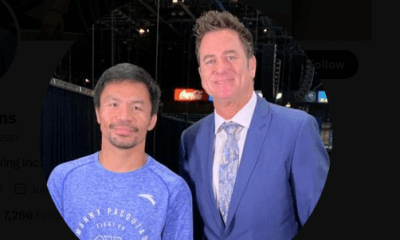

Featured Articles1 week agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 334: Back-to-Back Boxing Cards in the Big Apple