Featured Articles

TAPIA DOCUMENTARY Debuts TONIGHT on HBO

In a purely boxing sense, Johnny Tapia’s greatest victory was his July 18, 1997, points nod over fellow Albuquerque fighter Danny Romero. His worst defeat would have to be the first fight he ever lost as a pro, to Paulie Ayala on June 26, 1999, a somewhat controversial decision which was replicated, and even more hotly disputed, in their rematch on Oct. 7, 2000.

But many boxers understand that the toughest fights don’t always take place in the ring. Life on the street can be daunting, and even more so when daily battles continue inside someone’s mind, against unseen demons that intrude with such regularity that they become so much harder to conquer than any flesh-and-blood human being in the opposite corner.

As a fighter, Johnny Tapia was so driven that he could not abide even the notion of defeat. As a child and then as a man, he could not escape the memory of the murder/rape of his mother, a traumatic event which so tortured him that he sought relief from cocaine, which only worked until he required the next high that would again allow him to escape from reality.

In “Tapia,” which makes its debut Tuesday (TONIGHT) at 11 p.m. EST on HBO, viewers again see the many sides of Johnny Tapia, a five-time world champion in three weight classes who was just 45 when his tortured heart finally gave out on May 27, 2012. In 60 compelling minutes, during which Tapia and his steadfast manager-wife, Teresa, tell their stories of public triumph and personal tragedy, viewers will come to understand, as much as possible, the forces that prompted one man’s frequent journeys to hell and back. The good Johnny – devoted husband, loving father of three sons, fierce competitor inside the ropes – was a fleeting presence in the lives of those he cared about, often replaced by a drug-addled stranger whose addiction proved stronger than the more admirable shadings of his nature.

“I was a broken puzzle, ready to be fixed,” Tapia, his voice anguished, says of Teresa’s refusal to give up on him, when arguably the sensible and prudent thing would have been for her to run away as far and as fast as she could. “I have put her through hell more than anybody. She went through all the downs I went through, and she went through all the ups that I had. She should have left a long time ago, but she knew that there was a better Johnny in me.”

Perhaps that “better Johnny” would have emerged sooner, and to stay, had his mom, Virginia Tapia Gallegos, decided not to go dancing one fateful night in May 1975. Just eight years old, her son had a premonition that something terrible might happen.

“It was a Friday afternoon,” Tapia recalled. “My momma said that I was going to my grandma’s house ’cause she was going to go dancing. She liked to go dancing on Fridays and Saturdays. I didn’t want her to go. I begged her not to go. And she never came back. “They found some of her jewelry. About three days later, they said she was in the hospital. Four days later they said she was dead. It’s not like she got hit with a car. I wish it would have happened that way, (rather) than her being stabbed 22 times with an ice pick and raped. I still remember waiting at that door for my mom to come and pick me up. Let’s just say I still wait at the front door for her. But she’s never going to come back.”

The heinous crimes that resulted in Virginia’s death went unsolved for 24 years because key evidence against the perpetrator was misplaced, and lingering questions about the case lit a fire inside Tapia that burned hotly the rest of his life. Even when the assailant was identified with enough certainty that he surely would have been convicted, it was too late to bring him to justice; he had been killed by a hit-and-run driver eight years after his unspeakable violation of Tapia’s mother.

“There was a closure, in my heart, in my soul,” Tapia said. “They finally found out. I was kind of pissed off it took so long, so many years when they had the right guy right there.

“I wanted at him first. I was going to hurt him. But he died. A car ran over him three times. Maybe it was for the best. I’d have stabbed the s— out of him like nobody’s business. I still think about him. I would have (spent) the rest of my life in prison, no problem. Just knowing that I got him. Nobody ever touches my momma. I don’t care who you are, what you are, how you are. Nobody puts their hands on my mom. That’s the love of my life. That’s my queen.

“The saddest part of my life is outliving my mother. I tried to kill myself so many times. I always seemed to come back. I struggle with that every day. I want my mom. I can’t have her today.”

Taken in by his grandparents, the young Tapia lived in abject poverty, which often is the breeding ground of elite fighters. His grandfather, a former boxer, was “a real rugged, tough macho man,” according to Tapia, which made it all the easier for him to gravitate toward boxing and the discovery of a natural gift that was fueled in part by pain and rage.

But, even as he turned pro and began to rise in prominence, the meaner streets of Albuquerque – hey, every city has them – began to divert him, with the lure of gangs and drugs that sink their hooks into so many desperate youths.

“The first time I did (cocaine) I was, like, wow,” Tapia said. “I enjoyed it. That’s why I kept doing it. It was my mistress.”

And a most possessive one at that. Tapia was becoming a fixture of televised boxing and nearing a world title shot when he failed his first drug test in June 1990, setting into motion more such positive tests and, eventually, his arrest by Albuquerque police. Another arrest – for threatening to kill a witness in the murder trial of his cousin – came at the same time the New Mexico boxing commission was calling a news conference to announce Tapia’s suspension after he had failed still another drug test, and thus was revoking the conditional boxing license it only recently had granted him.

The raft of legal problems kept Tapia out of boxing for 3½ years, but that didn’t prevent him from fighting. He helped make ends meet by being paid $300 a pop for bloody scraps in which he took on all comers in a seedy bar’s oversized cooler, with almost all rules of pugilistic civility set aside.

Fortunately for Tapia, during his suspension from boxing he met a 20-year-old beauty, Teresa Chavez. They soon married, and it wasn’t long before her own resilience was tested, to the max.

“She was a source of stability for the troubled fighter to grab a hold of,” narrator Liev Schrieber intones. Which was good, because Tapia was anything but stable.

“She didn’t know I was a bad drug addict,” Tapia said. “I hid it from her. A couple of guys told her, `If you want to know where Johnny is, go to the restroom.’ She caught me. She was mad, mad, mad. But she didn’t know the real me. That night, I ended up dying on her. That’s how it started out for her as Teresa Tapia.”

Nine months later, Teresa—who took on the role of her husband’s manager in 1995 — locked him inside their small, rented house to help him quit drugs, cold turkey. For three weeks, he was a basket case, breaking everything in the house. But Teresa didn’t waver.

“She said, `Go ahead and break it. You’re going to fight pretty soon, you’re going to pay for everything.’ She said, `You can break everything, but I’m still going to stay here.’”

Tapia did go on to fight again, and very well, the “Baby-Faced Assassin,” as he was then known, capturing the vacant WBO super flyweight belt from Henry Martinez on an 11th-round stoppage on Oct. 12, 1994, in Albuquerque. There would be many other such good nights within the relative safety of the boxing cocoon, Tapia continuing to excel there even as he occasionally and predictably slipped in his ongoing struggle with cocaine.

Tapia’s re-emergence as Albuquerque’s hometown hero more or less coincided with the rise of another fighter from the same city, Danny Romero, who was seven years younger and cloaked in a squeaky-clean image that had never fit Tapia.

“I was already kicked out of boxing and he was coming up,” Tapia noted. “I was the bad guy, he was the good guy. I did the drugs and went to jail. He did everything good, you know? I came back into boxing, I was taking his spotlight. That’s when he started calling me out.”

It took nearly three years for the Tapia-Romero fight to be made, and when it took place, it was at the Thomas and Mack Center in Las Vegas instead of Albuquerque because of fears a venue in New Mexico’s largest city might be disrupted by the presence of gang members who wanted in on the action. With a heavy security presence in the arena, Tapia dispatched Romero in a humdinger of a fight, by scores of 116-112 (twice) and 115-113, in the process claiming Romero’s IBF super flyweight championship to go with the WBO version he already held.

Tapia’s new trainer, Freddie Roach – one of 11 trainers Tapia employed at one time or another – knew all about his troubled past, which, to his way of thinking, made his assignment all the more intriguing.

“He’s one of the greatest fighters in the world today,” Roach said of Tapia. “He’s probably the most exciting fighter in the world today also. He wouldn’t be Johnny Tapia without those demons, I guess. He’s just a strait-laced, real nice guy. He probably wouldn’t be as good as he is.”

But the demons Tapia had always been able to displace on fight night, or at least use to his advantage, deserted him in his first confrontation with Ayala. He entered the ring at the Mandalay Bay in Las Vegas with a 46-0-2 record, but left with his first “L” and bereft of his WBA bantamweight title.

“I gave it my all,” Tapia said, which obviously was true as that bout, as disappointing as it was to him, was named “Fight of the Year” by The Ring magazine. “Hey, everybody loses. That’s not a problem. But you don’t have to steal it from me.”

Tapia said he was more upset about the loss for Teresa’s sake than for his own. The only place he had never disappointed her was on fight night, and now he had.

“She keeps me going in life,” he said. “She keeps me strong. What I seen in her eyes, I let her down. I have before, quite a few times. But in the ring, I would never do that.”

Shortly after Ayala had smudged his previously undefeated ring record, Tapia had two mental breakdowns, and was diagnosed with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), bipolar disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. There were now explanations for his erratic behavior, if not necessarily excuses, but even prescriptions for symptom-alleviating medications could not rid him of his forever-present demons. He was getting older, not better, and, despite being paid a career-high $2 million for his Nov. 2, 2002, bout with Marco Antonio Barrera, he suffered a lopsided, unanimous-decision setback that again sent him careening to the edge of disaster. Another drug overdose left him in a coma. Again, he recovered. But he and Teresa must have sensed there are only so many comebacks anyone can make before that person runs out of miracles.

“Every time I look at Johnny, every minute we spend, I constantly will catch myself memorizing lines on his face and the way that he smiles because I always think that’s the last time I’ll see him,” Teresa said. “I’ve made it a habit, being married to him, not to think of tomorrow. You just don’t.

“And Johnny will tell you, `Never think of tomorrow because it may never come, and don’t think of yesterday because it’s gone. You have to live in today.’ That’s what I’ve learned to do with him.”

Perhaps there is no easily identifiable straw which broke the figurative camel’s back for Tapia, but if there were, it might have come while he was hospitalized after the Barrera fight. Robert Gutierrez, Tapia’s best friend, brother-in-law (he was Teresa’s brother) and nephew (he had married Tapia’s niece) was killed in an automobile accident as he sped to Albuquerque to be at Tapia’s bedside.

“That was my best friend,” a teary Tapia, no longer the “Baby-Faced Assassain,” said of still another heartbreak he had had to endure. “I felt that I killed him because I was in the coma. If I could take all that back, I would … I miss him.”

The heart failure that finally lifted Tapia from his earthly misery came one day after the 37th anniversary of his mother’s death. Call it a coincidence if you will, but the timing of his passing at least suggests that Tapia was simply ready to be greeted at heaven’s gate by the angel who had left him far too soon.

“I think if my mom was alive, I probably would have never fought,” Tapia said of the path onto which circumstances had steered him. It is a theory that can’t be proven, of course, but he leaves this mortal coil with indisputable words of caution for all who might be tempted to make some of the same mistakes he did.

“My message to the kids all over the world is, if you’ve never tried drugs, don’t do it,” he said. “The first time is a mistake, the second time’s a habit. Please, don’t do it.”

Kudos to those who make HBO Sports’ documentaries so compelling – executive producer Rick Bernstein and narrator Liev Schrieber, as well as fellow executive producers Lou DiBella and Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson and director Eddie Alcazar, who recognized a story that needed telling, and told it well.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThomas Hauser’s Literary Notes: Johnny Greaves Tells a Sad Tale

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

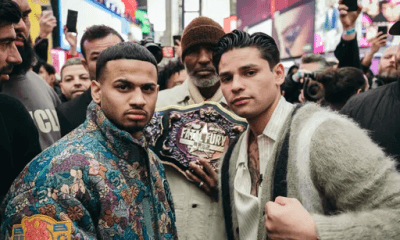

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRolly Romero Upsets Ryan Garcia in the Finale of a Times Square Tripleheader

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 324: Ryan Garcia Leads Three Days in May Battles

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

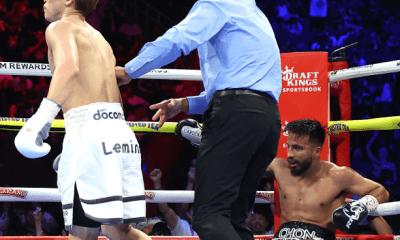

Featured Articles4 weeks agoUndercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More