Featured Articles

Gennady Golovkin and Roman Gonzalez: Pound-For-Pound Showcase

On October 17, a sellout crowd of 20,548 filled Madison Square Garden for a fight card featuring Gennady Golovkin vs. David Lemieux and Roman Gonzalez vs. Brian Viloria. These were fight fans; not high-rollers who’d been comped to get them into a casino. They arrived early and stayed late.

Golovkin (who’s the consensus choice for #1 middleweight in the world) and Gonzalez (who reigns supreme in the 112-pound flyweight division) are technically sound ring predators. Each man dominates opponents with hard precision punching and a pressure assault. With Floyd Mayweather’s retirement, they rank first and second on wide range of pound-for-pound lists. Lemieux and Viloria (15-to-1 betting underdogs) were brought in as building blocks for the stardom of their presumed conquerors.

Gonzalez entered the ring with 43 wins, 0 losses, and 37 knockouts. He’s unknown to most sports fans. But in recent months, there has been a buzz about him in boxing circles.

Roman grew up in poverty on the outskirts on Managua and is Alexis Arguello’s successor as “The Pride of Nicaragua.”

“I used to fight in the neighborhood and in the streets,” Gonzalez told Diego Morilla of RingTV.com. “I was lucky to meet Alexis Arguello when he opened a gym in San Judas. My father’s fighting name was ‘Chocolate’. He used to fight in his younger years and traveled to Cuba a lot. When we went to the gym for the first time to see Alexis Arguello, there were many kids around. Alexis said, ‘So you’re Chocolate’s son? Then you must be ‘Chocolatito.’ It stuck after that. When he realized I had some talent, Alexis placed a lot of attention on me. He took me under his wing during my amateur career.”

Gonzalez compiled a reported 88-and-0 amateur record and turned pro in 2005. Now 28 years old, he’s 5-feet-3-inches tall. Several times a year, he weighs the flyweight maximum of 112 pounds (about the same as a thoroughbred horse jockey). He has a high-pitched voice and, in street clothes, would blend unnoticed into a crowd.

References to God are sprinkled throughout Gonzalez’s conversation. “It is a great pride to represent my country,” he says. “I am the only champion that Nicaragua has right now, and that’s my biggest motivation to continue training more and more. Hearing my name announced away from my country is an extra motivation. When I hear people say ‘Chocolatito’ in the streets, I feel that everyone in Nicaragua is watching my fights and sending their blessings.”

This is the first time in a long time that boxing fans have paid much attention to the flyweight division. Viloria (36-and-4 with 22 KOs) said all the right things leading up to the fight. “Roman has his accolades for a reason,” Brian noted. “But I’m relaxed. I’m confident. I know I’m ready.”

If one was looking for a peg that Viloria could hang his hopes on, it lay in the fact that, at a media sitdown two days before the fight, Gonzalez was chewing gum and spitting periodically into a nearby trash can; a sure sign that a fighter is struggling to make weight. The following afternoon, that peg was whittled down considerably when Roman weighed in at 111.4 pounds.

Fighting Gonzalez is like fighting a tornado. But in the ring, there’s no storm cellar for sanctuary. Viloria started aggressively, getting off first and winning round one on all three judges’ scorecards. He also earned the nod from two judges in the second stanza. But he wasn’t landing much of consequence, and one had the feeling that it was just a matter of time before the tables turned.

Gonzalez is a relentless non-stop punching machine, who throws three and four-punch combinations to the head and body with pinpoint accuracy. They’re sharp, punishing blows. In round three, a chopping right hand put Viloria on the canvas. Brian fought back bravely, but his cause was hopeless. By round six, his punches had lost their sting and the issue was how Gonzalez would end it, not if. Referee Benjy Esteves stopped the beating at the 2:53 mark of round nine. Gonzalez outlanded Viloria by a 335-to-186 margin, including a 315-to-161 advantage in power punches.

Sitting with a handful of reporters before the final pre-fight press conference, Gonzalez had talked about how Alexis Arguello taught him to throw punches in combination. Roman also recounted a conversation he had with his mentor about Arguello’s first fight against Aaron Pryor.

Arguello told Gonzalez, ‘I hit Pryor with my best righthand. With that hand, I knocked everybody down. And nothing happened. At that moment, I looked to the sky and said, ‘Ay, mamita!’”

When Viloria was being pummeled around the ring, he could have been forgiven for saying, “Ay, mamita!”

Gonzalez-Viloria was followed by Golovkin-Lemieux.

Golovkin had compiled a 33-and-0 record with 30 KOs, including knockout victories in his most recent twenty fights. He has never been on the canvas as an amateur or pro.

Outside the ring, Gennady has a gentle demeanor that masks how brutally he practices his trade. During fight week, he appears as relaxed as a man who’s readying to play an important tennis match at his country club on Saturday night. In the ring, he’s methodical and focused. He has mastered the art of controlling the distance between himself and his opponent. The opponent is always in danger.

“My plan is my plan,” Gennady said after beating Martin Murray earlier this year. “It doesn’t matter what he is doing. Step by step. Box. Then finish it.”

Light-heavyweight champion Sergey Kovalev, who has sparred with Golovkin, told Ryan Burton of BoxingScene.com, “When we had the same training camp, we sparred a lot of times. His punches are not heavy but make you feel pain. Heavy is like a ‘boom’. His punches are more sharp, even more than heavy. He is a very hard puncher.”

And Fredde Roach, who trains Manny Pacquiao and Miguel Cotto, opined, “Golovkin is a great fighter. He’s strong. He has good fundamentals. He cuts the ring off well. I’ve watched his ring generalship. It’s effing great. Ring generalship is a lost art, but Golovkin has it. Ninety-five percent of the time, he’s in the right position. If you do that, you win fights. He’s heavy-handed. He’s a nice kid. I’m a big fan.”

Any doubts that people might have regarding Golovkin’s ring prowess are based on fights he hasn’t had. To wit, the lack of elite opponents on his ring record. By contrast, Lemieux (34-2, 31 KOs) was shadowed by two abysmal past performances.

There was a time when Lemieux was hailed as the future of Canadian boxing. Then, in 2011, he wilted against journeyman Marco Antonio Rubio and was stopped in the seventh round. In his next outing, he was brought back soft and lost again, this time by decision to Joachim Alcine (who has won only three of eleven fights since December 6, 2009).

The selling point for Golovkin-Lemieux was David’s “power”. Lemieux had won nine fights in a row after losing to Alcine, including a decision victory over Hassan N’Dam to capture an alphabet-soup championship belt. David was said to have “a puncher’s chance.” Indeed, the promotion kept likening Golovkin-Lemieux to Marvin Hagler versus Thomas Hearns.

But Hagler-Hearns was a toss-up fight. And as Jimmy Tobin wrote, “Lemieux wields his power with the nuance of child learning to use a spoon. Golovkin may not be the fighter of his mystique. But he would have to fall impossibly short of it to lose to Lemieux.”

An honest pre-fight appraisal of Golovkin-Lemieux was, “It will be entertaining for as long as it lasts.”

“Every boxer has power,” Golovkin warned. “The question is, ‘How much?’ I know my job. I think the knockout streak is not finished yet.”

When the fight began, Lemieux fought more cautiously than he usually does, which made sense given the fact that he was fighting the equivalent of a Sherman tank that’s firing live ammunition. At times, David tried jabbing. That didn’t work. At times, he tried fighting more forcefully to back Golovkin up, which is like trying to back up a brick wall.

Through it all, Golovkin moved inexorably forward.

To again quote Jimmy Tobin, “The ground opponents give Golovkin is usually shoveled onto their graves. Those who fire on Golovkin wind up no better, and very often worse, than those who choose to flee.”

In round five, a hook to the body sent Lemieux to the canvas, either as a delayed reaction or, more likely, because David took a knee to compose himself. Gennady then landed right to the jaw while David’s knee was down. Referee Steve Willis should have warned Golovkin for what appeared to be an accidental foul and given Lemieux time to recover. He did neither.

Lemieux rose and continued to fight. Those who remember the first bout between Roy Jones and Montell Griffin appreciate how differently David, to his credit, handled the situation. Lemieux fought courageously, but his cause was hopeless. At 1:32 of round eight, with Golovkin battering him around the ring, Willis stopped the carnage. Golovkin won every round and outlanded his foe by a 280-to-89 margin with a 110-to-54 advantage in power punches.

As for the future; Golovkin and Gonzalez will add to their collection of belts. But that’s no longer the point. Each man is pursuing stardom.

Madison Square Garden was far and away Gonzalez’s biggest stage to date. Team Golovkin is now outfitted by Air Jordan, and Gennady is featured in a new commercial for Apple Watch. The issue of Sports Illustrated that hit the newsstands during fight week devoted five pages to him.

As for pound-for-pound; Andre Ward, by choice, hasn’t fought a credible opponent since facing a debilitated Chad Dawson three years ago. And given Dawson’s dismal ring record since then, one has to go back to 2011 (when Ward bested Carl Froch) to find a true inquisitor.

Gennady Golovkin is #1 on my pound-for-pound list with Roman Gonzalez in second place.

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at thauser@rcn.com. His next book – A Hurting Sport – will be published by the University of Arkansas Press in November.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThomas Hauser’s Literary Notes: Johnny Greaves Tells a Sad Tale

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRolly Romero Upsets Ryan Garcia in the Finale of a Times Square Tripleheader

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoUndercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

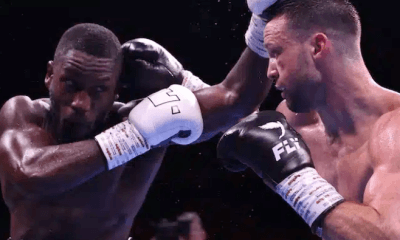

Featured Articles1 week agoEkow Essuman Upsets Josh Taylor and Moses Itauma Blasts Out Mike Balogun in Glasgow

1 Comment