Argentina

The 50 Greatest Lightweights of all Time Part Three: 30-21

It is normal, in my experience, to whet the appetite of the reader with a short introduction to the top thirty that promises below a collection of brutal and cognitive fighters so wonderful as to reward even the lightest perusal with head-shaking disbelief at the collection of brilliance assembled outside of the top twenty. In the case of the lightweights there is no need. Already, in Part Two, we’ve run across all manner of genius and thunder. We passed that threshold early, and for all time.

So below, just a continuation, then. This is the most incredible thirty through twenty-one I have yet arrayed.

#30 – Jack “Kid” Berg

In 1931, Tony Canzoneri annihilated Jack “Kid” Berg in just three rounds with the lightweight title on the line; in the wake of this slaughter, Berg was much reduced as a lightweight force, losing even at the domestic level as his career wound down to welterweight mediocrity. During his 1926-1930 prime, however, Berg was a lethal lightweight who lost just once, to Billy Petrolle, a defeat he avenged. Smouldering with violence in these five calendar years he devastated two of the very finest fighters of the era in Kid Chocolate and Canzoneri himself.

This is the difference between Berg and and Beau Jack, who ranks at #31. Both men were lethal, aggressive swarming destroyers, but when Jack crashed into the brick wall that was Ike Williams he was stopped. Given two latter attempts at his great rival he still delivered no wins. Berg, on the other hand, although twice beaten by Canzoneri, handed him what the New York Times was content to call “the worst beating of [Canzoneri’s] career”. That this victory is supplemented by not one but two victories over Kid Chocolate, another fighter of the highest class but as different from the seething, vaporous, feinting style of Canzoneri as it is possible to imagine, speaks highly for his own brand of chaotic devastation. Supplementary wins over ranked men like Gustave Humery, Billy Wallace and vengeance over Billy Petrolle, sees him locked above Jack in my eyes.

#29 – Alexis Arguello (77-8)

If further illustration was required of the disgusting depth of boxing talent at the 135lb limit, here is Alexis Arguello, one of history’s greats, hanging around at #29.

Arguello, of course, stepped boldly across the barriers for weight divisions and the full extent of his brilliance was hardly spent at the poundage, but Arguello dispatched fewer ranked men than every fighter ranked above him (excluding those who boxed before cognitive rankings were available). More, his first significant foray into the lightweight division ended in defeat to Vilomar Fernandez.

Fernandez was no powderpuff but the year before he had been crushed by Roberto Duran and dropped a narrow decision to a green Vicente Mijares. Clearly the smaller, softer man, Fernandez exposed Arguello’s greatest weakness, namely a lack of fluidity when mobile; Fernandez showed astonishing discipline in remaining on the move for ten rounds and the decision in his favor was just.

Arguello returned to 130lbs for the next two years before returning to 135 but when he did so, it was with a vengeance. First he stopped Cornelius Boza-Edwards in eight, showing all the spite in his punches that had made him the menace of the featherweight and super-featherweight divisions. Next was Jose Luis Ramirez, in a classic and desperately close fight. Ramirez barrelled Arguello onto his trunks with a southpaw-left in the sixth and I scored it for Ramirez by that single point. This scare in conjunction with the Fernandez fight made plain to Arguello that he would have to be at his best in pursuit of lightweight glory, and so he was. He stopped good, ranked men like Ray Mancini, Andy Ganigan and Roberto Elizondo, but when it got hard and he had to go the distance in his title fight with the rock hard Scotsman Jim Watt, the lessons learned against Ramirez were applied; he held the line.

28 – Jimmy Carter (81-31-9)

If you can track it down or are in possession of it, it is worth revisiting Pete Ehrmann’s 2007 Ring Magazine article on Jimmy Carter, which is about as fine a summary of the difficulties in ranking him as you are ever likely to see. To say Carter was something of a controversial figure is to put it mildly.

His 1952 loss to Lauro Salas was viewed as suspect, his 1955 loss to Bud Smith, more so. In the Smith rematch, bizarre judging saw the fight result changed three times. In perhaps the worst refereeing performance of the decade, Carter was allowed to splatter a featherweight named Tommy Collins for ten minutes, scoring one knockdown a minute in a nationally televised championship fight which brought coast-to-coast condemnation from viewers and press alike. His career was an absurd mess – despite the fact that he was a three times champion of the whole world with some wonderful wins over top opposition under his belt.

The best of these wins was in his first for the title. It’s true that the all-time-great power-punching technician that was Ike Williams was struggling badly with the lightweight weight limit by 1951, but it is also true that no lightweight had beaten him in six years. Carter, “a relative unknown even in his own hometown” according to the Associate Press, decked Williams four times before the referee rescued him in the fourteenth round.

This is a wonderful win. Carter has more than a few of them. He beat top contenders like Tommy Campbell and George Araujo and he beat champions Paddy DeMarco and Lauro Salas. The problem is that he beat Salas and DeMarco only after having dropped the title to them before scooping it back up in rematches. There were some bold souls who named the Mafia man Carter was supposed to be taking instructions from, one Frankie Carbo (he is worth a Google if you are not acquainted).

It is a fact that Ike Williams claimed to have been offered a bribe to lose before matching Carter, a bribe he refused (to his regret, having been beaten). In the end though, Carter’s wins, particularly the most impressive of them, stand under fewer clouds than those suspect losses. Carter, a three-time champion, is therefore impossible to ignore; but it’s with more than a little trepidation that I ensconce him in the top thirty.

A quick word about all those losses; the majority took place outside the weight range we are interested in and of those we are interested in, he suffered many of them as he wound down his career, broke and eventually forcibly retired by at least one boxing commission.

#27 – Willie Ritchie (33-10-16; Newspaper Decisions 12-4-1)

Willie Ritchie was fast-handed, was never stopped at the lightweight limit, and was the lightweight champion of the world between two of the golden eras in the history of the division.

His early achievements are paled by his title run between 1912 and 1914 but a victory over future welterweight demi-god Jack Britton is nothing to be sniffed at, and it is fair to say that when Ritchie cornered Ad Wolgast in a title ring – he had already got the best of the champion over a short distance in 1912 – he made no mistake, lifting the title on a disqualification after sixteen hard rounds of fighting. This was Wolgast at his prime, the United Press noting that “only Ritchie’s cleverness held the wildcat off.” Ritchie was a clever fighter, and one who as a youngster had seen Joe Gans spar, leaving him determined to emulate the Old Master. Probably, that was an impossible goal, but just like his hero, he was the lightweight champion of the world. He defeated Wolgast again via a reasonably clear Newspaper Decision (a minority thought it a draw) early in 1914, in between taking a decision from Leach Cross and stopping Joe Rivers. Leach, one of the era’s more pre-eminent contenders, was inconsistent but would himself go on to defeat Wolgast, and was a fine scalp; Rivers was of a similar type but was coming off a win over Cross. These are good, solid wins, but Ritchie has a couple of spectacular results tucked away also.

Later in 1914 he defeated Tommy Murphy who held a victory over Wolgast and Cross as well as the great featherweight Abe Attell, future welterweight champion Mike Glover and Owen Moran; Ritchie left him “badly shattered and soundly beaten” after twenty masterful rounds. Even better is a victory the record books show for him in a no-decision bout over Freddie Welsh 1915. Welsh had separated Ritchie from his title in 1914 when the San Franciscan took the brave step of coming to Britain to match the brilliant lightweight. In reality though, their rematch, fought as a non-title bout, was a tepid affair and the two men were booed from the ring.

Still, they all count in one way or another, and Ritchie’s tame vengeance over his enemy spoke of his excellence.

#26 – Lew Tendler (59-11-2; Newspaper Decisions 86-5-6)

Lew Tendler numbers among the best lightweights never to have won even a strap during his storied career and is not the first fighter we have encountered whose dream broke on the rock that was Benny Leonard. Tendler met him twice, firstly in New Jersey in 1922 in a fight which sold itself. Tendler wasn’t seen as just another opponent but rather as a legitimate test for Leonard who had ruled for five years. It proved to be the case. Lefts to the body and snapping southpaw rights to the face had Leonard bleeding and four rounds down after four. A sharp-shooting comeback saved him, however, and Tendler had to live with the crushed lead, but a wonderful eighth round – in which he nearly overwhelmed and dropped the champion – set tongues wagging. It also made Tendler’s all-time great bones, at least in the eyes of many old-time historians who would go on to set him in their top tens in the weight division’s history. The rematch was nothing like as close and essentially ran Tendler from lightweight, but before his meeting with Leonard, Tendler gave his peers reason to name him one of the greatest lightweights never to win a title.

Tendler twice won newspaper decisions over Rocky Kansas, although he dropped the most important of the three fights they shared, the judges picking Rocky in their 1921 contender’s meeting; his domination of Rocky in their 1917 contest was, however, near complete. He got the better of famed featherweight Johnny Dundee in all three of their encounters (ranked #51, trivia fans). He stopped Jimmy Duffy in eight, KO Chaney in one with a wonderful hook, straight left combo and holds a total of five wins (four at the lightweight limit) over Sailor Friedman.

A firm puncher who was stopped just once in over 170 bouts, Tendler was noted for both his courage and his smarts. A champion in any other era then, but every era has its champion – Tendler, in the end, was second best.

Second best to Leonard is no shame though, and although I find his placement by Nat Fleischer at #9 all time more than a little difficult to understand, it should be noted that plenty of water – not to mention lightweight wonderment – has passed under the bridge since Nat made his list.

#25 – Jose Luis Castillo (66-13-1)

Castlillo lost just three fights at the lightweight limit, two to Floyd Mayweather and one to Diego Corrales – fascinatingly, none of them hurt him. Not one of these losses sees a reduction in Castillo’s ranking. He’s not treated as unbeaten for the purposes of the process, but none of the losses he suffered sees him take a step down at the weight. Dropping two to Floyd Mayweather, including a decision that could, perhaps should, have gone his way, and losing that savage masterpiece he put on with Diego Corrales (LTKO 10) in May of 2010 have no shame attached.

But it was winning that made him special.

Castillo arrived on the scene in earnest in 2000 with an unexpected majority decision over Stevie Johnston. Busy, aggressive, insistent and showing a maturity that belied his lack of title experience, Castillo squeezed out the closest of decisions against the world’s #1 lightweight contender. The rematch, in which Castillo was able to win the crucial eleventh off the ropes showing a breadth of skill he often does not receive credit for, Castillo did enough to hold onto his strap in a fight the judges scored a draw (I agreed with them). Castillo followed this up with a sixth round stoppage of the giant Cesar Bazan, who gave Johnston all he could handle in two fights, before matching Mayweather for that pair. That he lost the first controversially is a matter for the record now; I’ve scored it several times and have never been able to see Mayweather with more than a draw. I won’t bang that nail here, it’s already as well embedded as it could ever be, suffice to say that for his legacy, this decision had serious ramifications. After Mayweather, Castillo defeated Joel Casamayor, Juan Lazcano and Julio Diaz, ranked one, two and four respectively. Had he defeated Mayweather and slipped that perfect right hand Corrales hit him with, we would be talking about a fighter in line for consideration for the top ten.

But boxing is what it is; Corrales did land that punch. And for all that Castillo could reasonably have received the nod over Mayweather once, the fight was close enough that a Mayweather decision is – barely – acceptable too. So Castillo washes up in the mid-twenties, something of a nearly man for all that.

#24– Ismael Laguna (65-9-1)

Ismael Laguna had pushed no less a figure than Vicente Saldivar to the very edge below lightweight before his arrival at 135lbs and so was a widely respected boxer before his April 1964 crack at the legendary champion Carlos Ortiz.

It is said by some that Ortiz was unwell that night in Laguna’s home country of Panama, but he looked well enough early, raking his light-treading opponent with a left-handed attack. At no time, in fact, did I have Laguna leading this fight until the thirteenth round after which he saw off a tired Ortiz for a narrow decision. His style is fascinating in this fight. Perched over his lead left foot, he turns square, a terrible risk against Ortiz, and leads with his right, almost an absurdity against Ortiz. He inverts his combinations, trashes the champion with uppercuts all the while remaining fleet of foot and swift of shoulder. But it is his offense, not his defense that wins him the lightweight championship and the greatest scalp of his career.

Ortiz, being Ortiz, avenged himself upon Laguna twice, reclaiming his title. That title passed from Ortiz to Carlos Teo Cruz, to Mandos Ramos at which point Laguna fought for it once more. He tried the right against Ramos, but the punch that did the damage was the jab, with it, Laguna sliced open the champion above both eyes, forcing his withdrawal in the ninth; Laguna had joined the select group of men to become two-time lightweight champions of the world.

In addition, Laguna twice bested top lightweight Frankie Narvaez, knocked out, then out-pointed ranked man Lloyd Marshall, boxed a draw with Nico Locche down in Argentina in a fight he probably deserved to win; in the very twilight of his wonderful career he out-pointed the world’s #9 lightweight Chango Carmona.

A wonderful fighter, he was unfortunate to run into another one, who was just a little bit better.

#23 – Ken Buchanan (61-8)

As a Scotsman, and a proud one (there’s no other kind), it gives me deep joy to say that Ken Buchanan is that other fighter, but it’s also important to outline how Buchanan earned those laurels. In short, he did it by beating Laguna. Twice.

They first met for Laguna’s title in Puerto Rico in September of 1970 amid a stifling heat not conducive to the best efforts of a pale, skinny kid out of Northfield. The word was that Laguna’s people were looking for a soft touch, “a patsy”. Buchanan was incensed.

“A f***ing patsy? Is that what they think of me? Get me the fight, I’ll show these people just what us Scottish patsies are like.”

He did just that, squeezing Laguna out of his title by the narrowest of margins, despite soaring temperatures (which, to be fair, Laguna probably didn’t enjoy all that much either), despite a bad cut to his weak left eye, despite fighting the last two rounds “beyond the limit” of his physical endurance, despite being in with one of the few fighters at the weight whose jab and movement were perhaps the equal of his own.

The rematch took place in New York, and seemed to suit Buchanan better. Certainly his performance was better and despite cuts and swelling to that left eye, he overhauled Laguna’s early lead on the cards to stage his one and only successful title defense. The rally he staged in round fourteen is one of boxing’s greatest.

Of course Buchanan was most famous for neither of the Laguna wins, but rather for a loss, to the man who would take that title, Roberto Duran. Buchanan felt that he had only lost that fight because of a foul blow and felt cheated over what he claims was Duran’s failure to take the rematch, even flying to New York in the late nineties to look for him and stage an impromptu rematch. He probably made a few local legends but failed to track down his old foe. But Duran has spent the intervening years between that fight and this date showering compliments upon Buchanan, naming him the most skilled fighter he ever met, a man in possession of the best jab, fastest footwork and the best defense of anyone he ever shared the ring with. This is astonishingly high praise and give that Buchanan was also in possession of a granite-jaw (stopped only in the fight with Duran), near limitless stamina (see his first tough fight with Laguna in that sweltering heat) and great speed and technical acumen (see any), Buchanan is only deadly punching power away from being one of the most complete fighters in history.

But he’s a Scotsman; he needs a tragic flaw.

#22 – George McFadden (46-13-21; Newspaper Decisions 3-7-7)

After his 1902 tilt at Joe Gans’ lightweight title, George “Elbows” McFadden went downhill fast, winning just eight of his last twenty-eight fights. In his prime, he must be named one of the greatest lightweight contenders in history, “a champion in any other era” according to Nat Fleischer. His 1899 campaign was ludicrous in its intensity, and saw him match no fewer than three lightweight champions a total of five times.

His April match with Joe Gans was McFadden at his absolute prime. He became, on that night, the first man to stop Gans. Described, before that contest, as a “practical newcomer to the upperdom of the fistic art”, he was out-weighed by no fewer than six pounds against a fighter capable of beating men who were bigger, never mind men who were smaller. McFadden gave “the most remarkable display of blocking ever seen in a local ring” according to the St.Paul Globe. “Gans tried in every way to get it on the New Yorker, but was invariably stopped.” Defensively brilliant, McFadden used his forearms and elbows to cut Joe’s punches off in flight. “My elbows,” he explained when asked about his nickname, “keep their fists away from their face.” After a typically slow start, McFadden “cut loose, took a lead, and was never again headed.” By the twenty-third, Gans was described as “manifestly distressed” by one ringsider, and the reverse one-two to the chin that ended matters was probably something of a mercy.

McFadden would match Gans twice more that year, posting a draw and a loss and although Gans would go on to dominate him in their wonderful seven fight series, that astonishing knockout victory all but guarantees his place on this list. But McFadden didn’t stop there. Less than a month after his victory over Gans, he was matched with the wonderful Frank Erne. Erne, in his prime, just like Gans, proved too much by a tiny sliver, winning by almost nothing in a fight one newspaper reported “read like a draw.”

After his July battle with Gans, which was drawn, he took on the legendary puncher, George “Kid” Lavigne. Lavigne hit McFadden’s elbow so hard that he couldn’t get his suit on after the fight, such was the swelling, and hit him so hard on the top of the head that he felt he was “walking on air” for the rest of the fight, but McFadden battered him back and put on such a brutal showing in the nineteenth round that he was able, finally, to keep Lavigne down at the sixth time of asking. It was the first and only time Lavigne would hear the “10” in his storied career.

In one year, McFadden beat a future all-time great champion in Gans, the recently deposed champion and the era’s most feared puncher in Kid Lavigne, and dropped a desperately close decision to the very next champion in Erne, all within a few months.

He did other stuff in his career, much of it impressive, but why bother running that down?

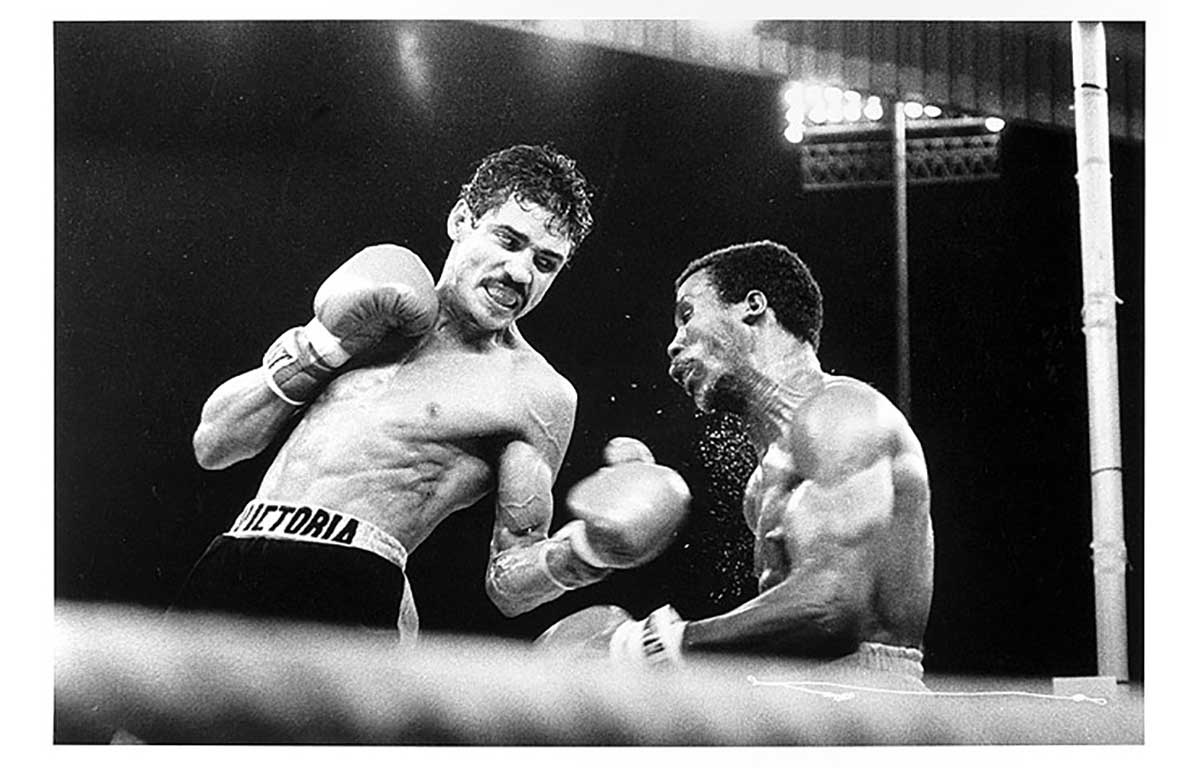

#21 – Esteban De Jesus (58-5)

Esteban De Jesus is most famous for being the only man to beat the animal, Roberto Duran at lightweight, but let’s begin by looking at his achievements outside of that astonishing victory.

First of all: five losses.

The first came against came in 1971 against Antonio Gomez. This loss occurred at featherweight (Gomez was a strap-holder). The second and fourth came against Duran; the third and fifth were against Antonio Cervantes and Saoul Mamby respectively; these losses were at the 140lb limit.

In other words, De Jesus lost to one man at lightweight and that was Duran. This is right next door to going all-together unbeaten at the weight.

As for those he bested, there were many and many of them were fine. Ray Lampkin was undefeated and ranked the best lightweight contender in the world when DeJesus matched him in his native Puerto Rico in 1973. DeJesus thrashed him, branded him with left hooks for two no-counts in the first and caught up to the reticent Lampkin again in the twelfth and last to seat him once more upon his behind. The rematch took place five months later and although no knockdowns occurred, DeJesus remained in control after an evenly contested opening third to take another decision. Lampkin wore the mark of the DeJesus left hook once more, his right eye sore and swollen.

Shortly after the Lampkin fight, DeJesus lost his rematch with Duran and then began to dabble with 140lbs, but when he returned to high level lightweight competition it was with a bang, against the warrior Guts Ishimatsu. Ishimatsu was then ranked #3 at lightweight, and DeJesus hardly lost a single minute of the fifteen rounds they contested. Feinting and moving the Japanese back early he was soon dominating him with a vast array of punches to both head and body, consistently keeping his opponent from settling. Fifteen round shutouts posted against quality opposition are rare indeed, but that was how I saw this fight, and also how it was seen by one of the judges in attendance. His brutal fluidity in the closing rounds after so much heavy punching early in the contest almost beggars belief. For his very next trick, he brutalized the #4 contender, Hector Julio Medina in seven. Medina had been 28-0.

Which returns us, neatly, to that victory over Duran. He, too, was undefeated when DeJesus stepped into the New York ring where he would rip that record from him via ten round decision. DeJesus was outstanding, unclenched, his timing delightful. His approach to boxing was simplicity itself: if you see a punching opportunity, punch. This leads to the extraordinary site of him landing lead right hands against the reigning lightweight champion of the world. Duran didn’t look his best in this fight, and there are those that claim he did not train properly for this fight. If that is true, more fool him – for Esteban DeJesus was a beast.

More beasts appear, over the horizon.

Check out The 50 Greatest Lightweights of all Time Part Two: 40-31.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles8 hours ago

Featured Articles8 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden