Featured Articles

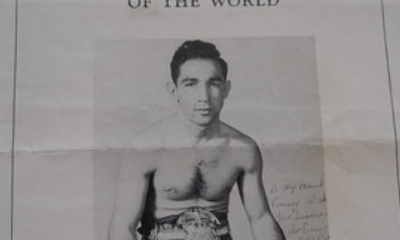

Aaron Pryor (1955-2016): How ‘The Hawk’ Learned How to Soar Again

Aaron Pryor – True greatness in boxing almost always comes in measured doses. The best of the best shine brightly in the ring for just so long, but, if they stay too long in the cruelest sport, their luminescence begins to ebb, sometimes with startling rapidity. The decline of a special fighter’s gifts might owe to the natural aging process, or to accumulated wear-and-tear on his body. Occasionally, though, it can be attributed to the same temptations that can wreck the lives of anyone else: drugs, booze, gambling, the wrong sexual partners or some combination thereof.

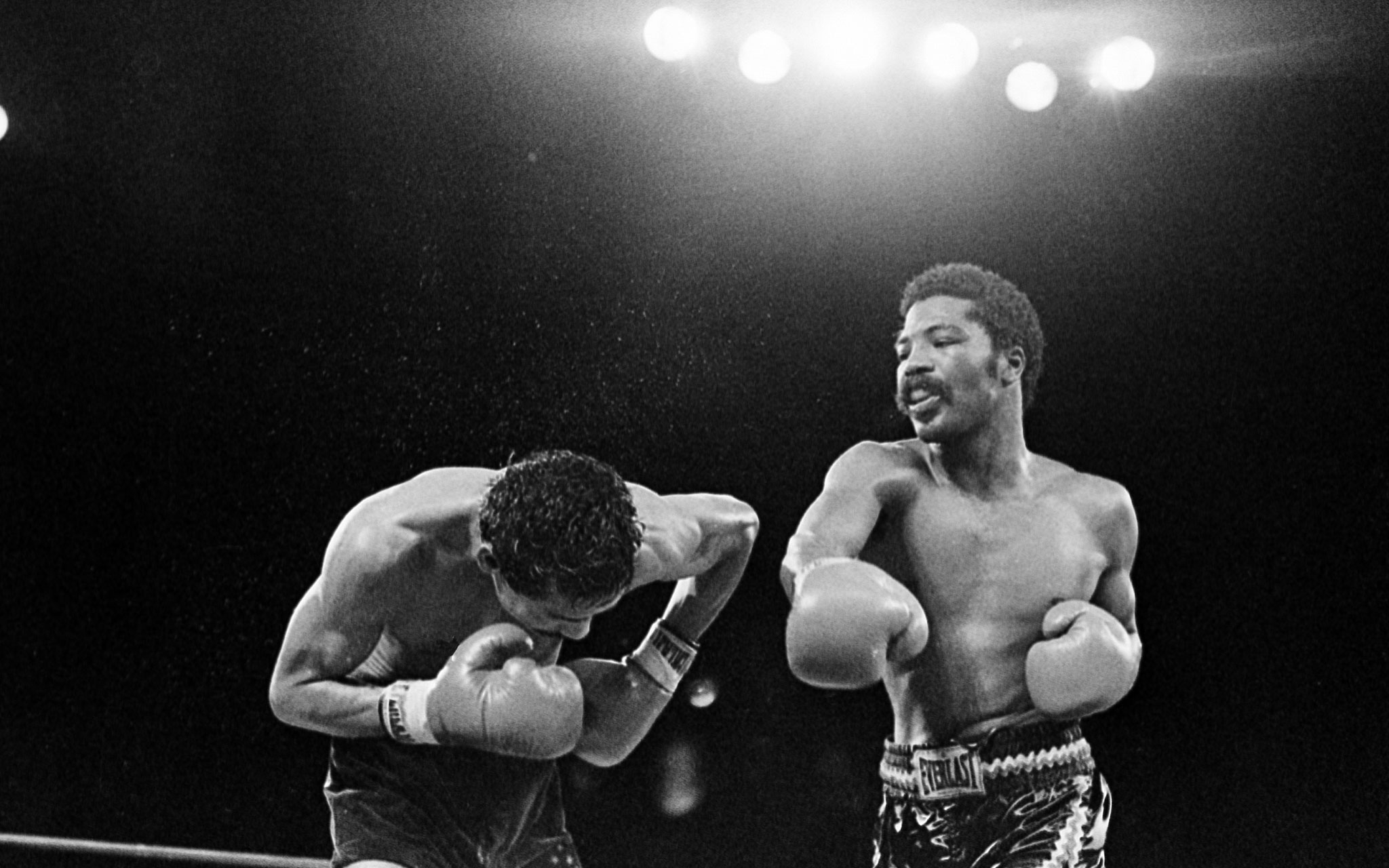

Two-time former junior welterweight champion Aaron “The Hawk” Pryor failed to make it to his 61st birthday by 11 days, passing away Sunday at his home in Cincinnati, Ohio, at 5:57 a.m. The cause of death officially was listed as a loss on points to a persistent foe, the heart disease he had battled for a number of years. But those who knew him or were aware of his glorious yet tragic story know better. Perhaps the most dominating 140-pound boxer the world has ever known, Pryor began to die in increments the moment he first succumbed to the siren song of cocaine in September of 1983, just days after he had knocked out Alexis Arguello in 10 rounds in a more dominating rematch of their certifiable classic of a first meeting. In that memorable test of skill and wills, “The Hawk” finally put away the rawhide-tough Nicaraguan superstar with a barrage of punches in the 14th round on Nov. 12, 1982, at Miami’s Orange Bowl Stadium. So furious was Pryor’s final assault that it was a full four minutes before an out-cold Arguello regained consciousness.

“It was like a miniature `Thrilla in Manila,’” lead promoter Bob Arum said of a war widely considered to be the top fight of the 1980s, and one of the most exciting ever in the annals of boxing. “It went one way, then the other way.”

After Pryor defended his WBA junior middleweight title for a seventh time, on a seventh-round stoppage of Sang Hyun Kim on April 2, 1983, in Atlantic City, N.J., his no-doubt-about-it demolition of Arguello in the much-anticipated rematch should have had him at the top of the world. Personal contentment, though, had always been more elusive to Pryor than success inside the ropes, no matter how many members of his unwieldy entourage were around to stroke his fragile ego. Even as he rose to the peak of his profession, Pryor – who grew up as one of society’s outcasts, and who left his dysfunctional family at the age of 14 in search of the love he had never known – was sinking into a morass of recriminations and self-loathing. He took his first hit of the insidious white powder in the aftermath of the second Arguello fight, in his adopted hometown of Miami, where pharmaceutical escapes from reality were as much a part of the landscape as palm trees and white-sand beaches. The career slide Pryor might have avoided entirely or delayed for at least several years became a free-fall into which he lost not only most of his material possessions, but, more importantly, his pride at what he had accomplished and his sense of self.

Although Pryor, who had vacated his WBA junior middle title because of inactivity, won the vacant IBF version of the championship on a 15-round unanimous decision over Nick Furlano on June 22, 1984, in Toronto, and defended it on a split decision over Gary Hinton on March 2, 1985, in Atlantic City, his life had become one hot mess. As his addiction, taxes and alimony from two failed marriages ate away at ring earnings that seemed downright modest when compared to those amassed by such contemporaries as Sugar Ray Leonard and Roberto Duran, the hangers-on began to drift away and Pryor was reduced to a shell of his former prominence in every way.

“After Buddy (LaRosa, his estranged manager) took his half, the government took its half (of what was left),” Pryor said in 1995. “Then after that, my wife at the time had to have her half. After everybody got their half, I didn’t have half of nothing.’”

Pryor’s fall from grace was spectacular in its totality. He was sentenced to prison on a drug conviction in 1991, and the following year he was a homeless crack addict living on the streets of his hometown of Cincinnati, shadowboxing in alleyways for handouts that might allow him to score his next drug hit. At one point his weight had dwindled to 100 or so pounds, although he was too ashamed to step on a scale, and more than once he considered suicide as a means of ending his misery. He spoke of putting a gun to his head and a knife to his chest, but the man who was so absolutely fearless when it came to trading punches with world-class fighters admitted to lacking the courage to pull a trigger or plunge a blade into his broken heart.

The story did not end on that despairing note, of course. Like any number of fallen fighters who went before him or have since, Pryor decided enough still remained of what had made him dangerous to attempt a comeback. But there was no evidence that any trace of the once-spectacular Pryor existed when he was stopped in seven rounds by a fair-to-middling welterweight, Bobby Joe Young, on Aug. 8, 1987, in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. It was Pryor’s only defeat in a career in which he would finish 39-1, with 35 knockout victories.

But Pryor pressed on nonetheless, stopping ham-and-eggers Hermino Morales, Darryl Jones and, finally, Roger Choate before stepping away from the ring for good in December 1990. It was for the Jones fight, on May 16, 1990, that I made the trip to Madison, Wisc., to chronicle what had by then become for Pryor a quest that was in equal parts sad and curious.

Pryor’s bid to be granted boxing licenses in Nevada, New York and California had been rejected on medical grounds that he was legally blind in his left eye, having undergone surgeries to repair a detached retina and to remove cataracts. With nowhere else to turn, he sought redress in Wisconsin, a state that has long viewed itself as a bastion of progressive politics and protector of civil liberties. In short, Pryor believed he would be allowed to fight in that state because he met the standards of being a handicapped person, which afforded certain protections under Wisconsin’s tough anti-discrimination statutes.

“This is bad for boxing and bad for the state of Wisconsin,” said Dr. James Nave, the then-chairman of the Nevada State Athletic Commission which had voted, 4-1 the month before against licensing Pryor to box in that state. “We spent a tremendous amount of time researching this case and I don’t think Wisconsin looked at what we did before coming to a decision.”

Taking a somewhat different viewpoint was Marlene Cummings, secretary of regulation licensing in Wisconsin, who said she had no choice but to approve applications submitted by Pryor and clearly diminished former heavyweight contender Jerry Quarry.

“Everyone has due process in this state,” Cummings said. “Aaron Pryor and Jerry Quarry met all the standards required to be allowed to box here. I’m certainly aware that officials of other states have arrived at other decisions, but I am obligated to follow the laws of Wisconsin. I can’t take one law and hold it out by itself. We’re very serious about being fair in this state.”

The Pryor-Jones bout drew approximately 400 spectators in the 1,200-seat Masonic Hall, still another reminder of just how far Pryor had tumbled from that magical night in Miami when he and Arguello electrified 23,800 on-site fight fans and a nationwide HBO audience by reaching deep inside themselves and finding whatever it is that can elevate a boxing match to heights of courage and determination seldom glimpsed in any athletic arena.

But his trips to Madison and Norman, Okla., where he stopped Choate, were not the figurative end for Aaron Pryor, nor was his descent into the drug-induced haze with an 800-pound gorilla on his back that he either couldn’t or wouldn’t toss aside for so long. There would be another triumph for “The Hawk,” maybe one even more significant than his twin batterings of Arguello, with whom he is destined to forever be linked.

There would, finally, be love, in the arms of his third wife, the former Frankie Wagner, herself a recovering cocaine addict. Pryor was cleansed, as much as anyone can hope to be, of his drug cravings and any lingering demons, when he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1996. He would return to Canastota, N.Y., for IBHOF induction weekends 20 times in all, the most recent in June of this year, to soak in the adulation he had earned with his fighting heart and perpetual-motion style.

“It’s like a dream that comes true every time I’m here,” a fitter, happier Pryor told me in 2013. “You can get hooked. If you come once, you’re probably going to come year after year after year.

“To me, it’s one of the greatest feelings you could ever have to come to this special place. I look forward to it like a little kid looks forward to Christmas. The fans just take you in. They embrace you. If the Hall of Fame was in, say, New York City, I don’t think it would feel the same. Too many different things to do or see there. Here, it’s all about boxing for four days.”

It is a remarkable thing, witnessing two legendary adversaries like Pryor and Arguello bonding years later as the result of the respect each earned from the other on a roped-off swatch of canvas. And when Arguello, 57, died on July 1, 2009, reportedly by his own hand (although many continue to believe foul play was involved), Pryor admitted to still being shaken 11 months later during his next trip to the IBHOF. It was as if a part of him had died, too, with the part that remained awaiting summoning to the other side of the celestial divide.

Gen. George Patton once observed that “all glory is fleeting,” but that is not always the case. Lives end, but for a select few glory endures beyond the grave. It is destined to be that way for Muhammad Ali, who also departed this mortal coil in 2016, and within the strictures of boxing, it as likely to be that way on a lesser scale for Aaron Pryor, who found redemption in the ring and, ultimately, outside of it.

“Aaron was known around the world as `The Hawk’ and delighted millions of fans with his aggressive and crowd-pleasing boxing style,” Frankie Pryor said in announcing her husband’s passing. “But to our family, he was a beloved husband, father, grandfather, brother, uncle and friend.”

Pryor is survived by his sons Aaron Pryor Jr., Antwan Harris, daughter Elizabeth Wagner and grandsons Adam, Austin and Aaron Pryor III.

Thanks for the memories, Hawk.

Aaron Pryor / Check out more boxing news and videos at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave