Argentina

The Rise and Fall of the People’s Republic of Al Haymon

The year of 2016 was a rocky one for Al Haymon and his PBC outfit. And 2017 appears to hold a lot of gray clouds in the horizon, according to the latest forecasts.

Reports abound about the depletion of his war chest, the growing complaints by formerly pampered and overpaid fighters who feel abandoned by Haymon, the threat of lawsuits by fellow promoters and managers as well as from disappointed investors, and much more.

And because of this, perhaps now more than ever, there are more questions than answers about the dealings of boxing’s self-appointed almighty ruler. Is he out to monopolize boxing altogether in a UFC-style chokehold, or is he the guy who will free boxing from the shackles of its current business model to make it more profitable for fighters and more affordable for the fans? Did we expect too much from him or did he set himself up for something that he was unable to achieve?

Is the scheme working?

For an in-depth analysis, let’s allow the hand of history take us through a journey of enlightenment in our search for clues about the possible outcome of what is already considered the most ambitious power grab in all of boxing.

Chapter One: (Not Just) Another Brick in the Wall

Legend has it that the Jiayuguan Pass, one of the most magnificent gateways of the Great Wall of China built during the Ming Dynasty, was designed by an extremely meticulous architect who calculated that exactly 99,999 bricks would be needed to complete the project. Upon receiving his request for materials, his supervisor scolded him for his arrogance and told him that, if his calculations were short or long by as much as one brick, he would personally condemn the architect to three years of hard labor.

Here, the legend takes two different directions. One says that the architect stood by his calculation and, upon finding out that there was an extra brick left, placed it on a cornice to be seen by the supervisor and told him that a supernatural force had instructed him to place it there, in order to magically stabilize the entire building. Another version, however, says that the architect did indeed respond to his supervisor’s admonition by adding just one more brick to his request, and that after completing the building he left the extra unused brick on the cornice as a proof of his acumen.

In both versions, however, the brick remained on the cornice many years after they died – and it still does today.

___________________________________________________________________________

As true or not as this story can be, we can assume that nobody really bothered to count the bricks or to truly ascertain the architect’s arrogance in any other way. But we are in a different environment today, and Haymon’s bricks are being counted, one by one, as if boxing’s future depended on it.

The final count, as it turns out, might take some time. Just as in old-school masonry, Haymon has sought to keep his trade secrets in the hands of the architects, but a few lawsuits and public documents have given a few clues about the elusive Haymon’s business dealings. And the numbers, in some cases, don’t seem to add up.

Regardless of the final tally, it would now appear that the entire Haymon magic castle of the 99,999 bricks is indeed a Jenga game in which one or two missing bricks could cause a collapse of gigantic proportions. The problem is (and still is) that only Haymon seems to know which one of the bricks is going to cause his empire to collapse and which are the ones holding it together.

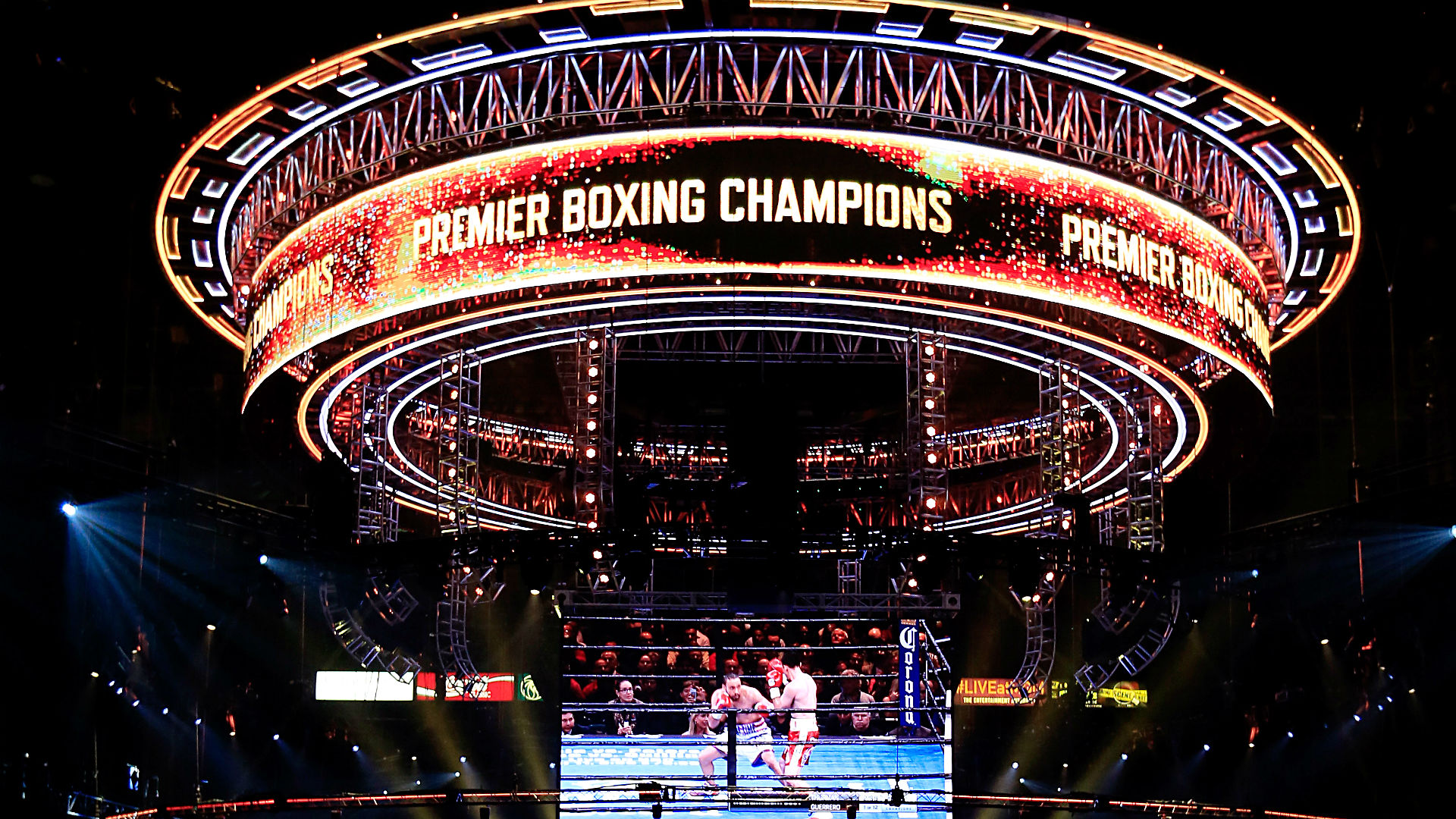

Since its inception in March of 2015, Premier Boxing Champions became a unique proposal with very few parallels in boxing history. No belts from any organization are shown or announced in the ring, especially since they removed the ring announcer altogether. A huge screen in the background provides information on both combatants as the fight goes on, a savvy promotional tool when it comes to building up young fighters. The ring area looks extremely neat, with blue and red enclosures preventing entourages and ringsiders into the work area of each fighter. And no entourages or other side shows are allowed into the ring at any time.

The aesthetic changes, of course, paled in comparison with the deeper changes brought along by Haymon and his crew. Boxing made a triumphant return to free network television, with multiple shows on NBC, FOX, ESPN, CBS and as many as six to eight other networks. Fighters began making significantly better paydays than in their previous engagements, and they retained their ability to pick their opponent. Participants were mandated to take Olympic-style drug tests and periodic medical exams as part of their contract. Life was good.

But the problems would begin to surface soon enough. To some, the whole thing was missing a brick. To others, there was one brick too many in the already extensive new secret rulebook that exists only in the mind of boxing’s new Demiurge.

Without the title belts, there were no pressures and no mandatory challenges to keep the game interesting, as it turns out that overprotecting guys who are supposed to build up their dislike for each other and then turn it into a physical confrontation for profit and amusement tends to wax and wane their desire to engage in do-or-die fights. The free network TV model backfired when fans, far from being grateful about the outpour of fresh boxing action each week, began complaining about the quality of the action. Soon enough, the fighters began complaining about the lack of action after finding out that belonging to the same stable of fighters (with a roster going well into the hundreds) sometimes creates conflicts of interest that keeps certain fights from happening. Many headliners went from belle of the ball to booty call in a matter of months, and the unrest is growing.

The “payola” model denounced in several lawsuits against Haymon began imploding as well, with investors wondering out loud how wise it was to pay for air time that the networks used to pay for themselves in the good old days. The idea that Haymon receives a 10% fee from every fight he puts together, regardless of the income generated by the fight itself, turned the whole thing into a ‘pyramid with a revolving door’ in the minds of the already wary bankrollers.

And of course, all of those tribulations did not make the fine print on those contracts disappear at all. To some, the Olympic-style drug tests and periodic medical exams mandated by the company are thoughtful measures of care for their well-being, but there have been no shortage of questions about the true purpose of those tests, with a few people wondering out loud about who truly owns those medical records and whether they can be used against the fighters to extract information in the event of a lawsuit somewhere down the road.

Of course, all of these questions could be easily answered in a few interviews with the man himself, but Haymon’s reclusive nature is keeping the boxing world in the dark, and obtaining information about the underlying numbers of his operation has proven harder than obtaining Donald Trump’s tax return information. But there are enough clues out there to provide a more accurate overview of Haymon’s next steps.

The problem seems to be that those who hold the clues are the ones who benefit from them. But as the rewards thin out, so does their patience. And what used to be music to their ears is now an alarming, buzzing noise.

Chapter Two: Hooked on Haymonics

Legend has it that some 2066 years ago, a young Roman general found himself standing sleepless on the banks of a tumultuous river. Brash, arrogant and boastful, the young leader was making his way back home after spending most of his professional life conquering new land for his empire, hoping that his heroism would turn him into a hero and eventually propel him into power in spite of the opposition by the ruling class. As he stood facing the roiling waters, he kept reminding himself that taking his troops across the river would not only be considered an illegal action contrary to an order issued by the Senate, but it would also constitute treason and even the beginning of a civil war.

But as successful as he was fighting and conquering barbarians, he was defenseless against his own ambition. Undaunted, he summoned his troops at daybreak, and ordered them to cross the Rubicon towards Rome – and into the history books.

History is still inconclusive about the phrase that the great Julius Caesar used to usher himself into immortality. One version has him exclaiming “the die is cast” as he led the charge, some others have him saying “let the games begin.”

The inceptive nature of this brazen act of defiance as an inspiration to tyrants and despots worldwide for many years to come, however, remains undisputed.

Let’s talk a little bit about boxing business.

Boxing is the ultimate self-made-man scheme. It is a truth machine, both in and out of the ring. Each fight is a league or a season of its own. Each fighter is a small business and a one-man band. Success and failure are the product of impromptu decisions, be it the direction and trajectory of a punch or a decision to challenge one fighter instead of the other.

Haymon, a 62-year old Harvard educated former music and comedy promoter who made his mark in the business world promoting some of the most successful acts in the world, sought to reverse this entire model by going to a group investors and asking them for money to turn boxing into a hit-making machine. Boxing was to be sanitized, properly organized and turned into a UFC-like model in which fights are made by moving pins on a corkboard and organizing them into brackets leading to an imaginary championship or a once-in-a-lifetime payday.

The first leg of the PBC was meant to be the sport’s biggest infomercial ever, and then the orders would come in by the millions. But one thing is selling burger grills, and another one is selling trips to the slaughterhouse to see how burgers are made. The idea that more casual sports fans would turn to boxing overnight just because it is on free TV is akin to believing that people will become vegetarian in throes if we place enough juice-maker infomercials on late-night TV. And here we are, hundreds of billable hours later, and hours upon hours of juicing, and it seems that selling parsley and carrot juice is still as tough as it was on the first day.

Now, the model is being tested to the fullest. The teaser fees are disappearing, the funds are drying up, and all those juice makers are still gathering dust somewhere. And there’s still plenty of explaining to do with the investors. Beating the competition is the ultimate goal in capitalism, but eliminating the element of competition in a business built around the sport that exemplifies competition like no other sport on Earth is hardly a recipe to Make Boxing Great Again. It is increasingly clear that it will take much more than the will and the ambition to move troops across a river of doubt and reluctance to conquer the hearts and minds of the boxing faithful.

Matchmaking is an essential part of success in boxing, and it requires knowledge that transcends the sport to include many other variables, not just making fights that will look good on TV. Let’s imagine for a minute the chaos and disaster that would ensue if someone allowed TV ratings to dictate baseball lineups and basketball brackets. Sports leagues have a way of letting the athletes dictate their own success through their own talent and then allow the fans and the press to build storylines around that, and boxing invented that type of mobility. Trying to attack the problem from the opposite direction by hiring a group of talented fighters and dictating the networks how to showcase their inevitable progress and success is ignoring the true nature of the sport.

The comparisons with the control-heavy UFC model abound, but are there really any serious parallelisms? It can be argued that MMA has benefited from the creation of the UFC and the business savvy of its creator Dana White. Thanks to him, a fringe sport with unclear rules and practically no previous existence in the mainstream was sanitized, packaged and commercialized successfully. But boxing is a completely different sport, with only pain and blood to be accounted as similarities.

Boxing had its own way of creating and promoting fights, which by nature required hostile actions to be taken by fighters who commit to the destruction of their opponents as the main selling argument of their product. In the UFC, violence and gore are promised but not always delivered, fighters are apparently not free to challenge each other publicly, and matchups are dictated by the management. Boxing would survive for less than a week under those premises.

Haymon’s model so far seems to move freely between the socialist idea of paying more money to fighters for less work, and the ultra-capitalist idea of monopolizing all the action and making the most money and then allowing that money to trickle down to the less fortunate. But neither trick is working. The elite is becoming complacent and the working class is growing impatient. Stars sit at their homes waiting for the call to face the Rod Salkas du jour, while the second tier of champions and contenders languish in the backburner waiting for their annual event, at best.

Perhaps Haymon is imagining a scenario in which boxing becomes a show that people watch again and again regardless of their protagonists, just for amusement. But boxing is the realm of those who embrace drama as entertainment, not just an empty display of courage and will. Boxing is not a song or an artist that you can turn into a hit and then cash in on them from a dozen different sources. Boxing is jazz with tickets priced at the Michael Jackson level, and on a huge worldwide stage. And we all know what boxing philosopher George Foreman has said: boxing is like jazz because the better it is, the less people understand it. It’s a one-time thing, each fight is a universe of its own, and each time has to count.

Even so, there are plenty of people who think that the model is not entirely wrong. Every grand plan has its fair share of miscalculations, and we could be the ones not doing the math correctly. But it is also possible that Haymon’s unrequested bailout of boxing could easily turn into the vaccine that no one ordered – and which may indeed cause autism.

But the clock is ticking, the bell is about to ring on the Boxing Stock Exchange and payment is due. Will the gamble be worth the risks? And if not, will boxing recover from this brutal reshuffling of its entire modus operandi?

Chapter Three: Knocking on the Palace’s Door

Legend has it that during the US-backed military coup in the Dominican Republic in 1962, president Juan Bosch sat in his office at the presidential palace, waiting peacefully to be removed by force as 42,000 Marines stormed into the country to support the rebels. During his final minutes as a democratically elected leader about to be overthrown by a foreign power, and as his spirit and his belief in justice were being tested, Bosch was asked by a journalist whether he hated America or not.

Bosch, a humanist and a brilliant writer and novelist in his own right, responded in a way in which only a veteran statesman could reply.

“I do not hate them, sir, because no one who has read Mark Twain could ever hate America,” said Bosch. “What I do hate is imperialism, which is a completely different thing.”

Legends and hearsay traveling through centuries and subjected to hundreds of misquotes and mistranslations are hardly reliable enough to be taken as reference. But in this case, legends and hearsay are pretty much all we have to decipher Haymon. The facts are scarce, but they are slowly coming to light.

The largely failing Muhammad Ali Act, an unpatrolled and unenforced piece of legislation, has created some grounds for oversight and legal action that has proved to be very revealing. But one of the big failures of the Muhammad Ali act is the childish semantic change from ‘manager’ to ‘advisor’ to define those who handle a fighter’s business. This has allowed Haymon to have some type of claim that he is neither, both or none of the above depending on his convenience.

But the truth is that (wait for it…) a promotional outfit needs a promoter. Yes. You can do away with the ring card girls, the ring announcer and other expenses, but you do need the gabby Harvard-grad orator or the loudmouth and colorful character with the funny hair on a podium claiming that there will be no other fight like this one ever in history and that you are a sucker if you don’t buy it, especially with that lovely PPV rebate offer on that six-pack of beer that you’re going to buy anyway. There is no replacement for that.

Granted, Haymon will never be Bob Arum or Don King, but he could have been the best of both worlds. As both a Harvard graduate (just like Arum) and an alumnus of Cleveland’s John Adams High School (where King graduated in 1951), Haymon could have conjured the Ivy League guile and the street smarts of the school of hard knocks to create a unique promotional persona. He didn’t, and as hard as it seems after years of putting up with both of them, boxing will one day miss the duels between Arum’s quick humor and King’s over-the-top flurries in his colorful ghetto-ese.

But barring a catastrophe, it is hard to envision a day in which Haymon will be remembered as a villain, because it is difficult to hate someone who has brought boxing back to free network and cable TV, who has worried about providing health care to his fighters, and who has sought to pay fighters their fair share while giving them the safest and easiest work possible.

What will tarnish Haymon’s legacy, we believe, is his shady and never fully explained motivation to turn boxing into his own little empire, a magical realm in which the most basic premises of a centuries-old sport and its time-honored customs are completely overhauled on a whim.

The change of year will provide an excuse for people to give him some more time before making a final judgment on Haymon’s business practices. But this task can’t wait. On what country, empire or leader is he basing his business model? Will Haymon be remembered as King of Haymonia, president of the Republic of Haymonica, or deposed dictator of the failed People’s Republic of Haymon? Should we ask Haymon what he has done for boxing, or shall we instead ask what boxing can do for Haymon to succeed?

Is there a magical brick that will hold Haymon’s grand structure together? Will the last brick remain on the cornice of his imperial compound as proof of his genius for us to see and humbly admire? Will he have to forcibly sail across yet another river to attempt another hostile takeover of boxing with a new magic formula?

Did Haymon fail boxing, or did boxing fail him?

Whatever happens, hopefully the world of boxing will not find enough reasons to hate him for his intrusion.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles13 hours ago

Featured Articles13 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden