Featured Articles

Riddick Bowe’s Marine Corps Misadventure

The snide remarks stung then, probably more than any legal punch he received from Evander Holyfield or even the illegal ones below the belt landed by Andrew Golota. Twenty years later, they probably still haunt Riddick Bowe as the Ghost of Christmas Past tortured Ebenezer Scrooge. If there is a difference, it is that Scrooge’s vision was private, and in it he found ultimate redemption. For Bowe, who enjoyed so much success in the ring and so little of it at the United States Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island, S.C., those 11 days of chasing a boyhood dream became an exercise in humiliation that has yet to fully cease. Perhaps the taint of it all will endure forever, as will the glory of his epic, three-bout trilogy with Holyfield.

Riddick Bowe wasn’t as good a Marine as Gomer Pyle.

Once he washed out of the Marines, Bowe should have become a UPS driver. That way he’d at least get to wear a uniform.

The Marines are looking for a few good men, and Riddick Bowe ain’t one of them.

There are worse things for a former heavyweight champion – one whose accomplishments include a silver medal at the 1988 Seoul Olympics, ring earnings estimated at between $65 million and $100 million, depending on whose figures you choose to believe, and his 2015 induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame – to endure than 11 days of discovering that some boyhood dreams are best left in one’s boyhood. Since he voluntarily separated himself from the Corps on Feb. 20, 1997, probably as much to the Marines’ relief as to his, the man known as “Big Daddy” has seen his fortune disappear, his mental and physical health diminish, his family and so-called friends drift away, and his otherwise commendable legacy at least somewhat tarnished.

Many of the sad and bad things that have made Bowe’s rags-to-riches story a cautionary tale of how easy it is for the process to be reversed likely would have happened regardless of whether he raised his right hand and taken the oath of enlistment on Feb. 10, 1997. Was it a just a publicity stunt to call positive attention to Bowe’s then-sputtering boxing career, or to the USMC? By all rights, Bowe, at 29, should never even have been considered as a candidate for Semper Fi-dom; the age limit for joining was 28; at 6-foot-5 and a bit north of 250 pounds, he was more than 20 pounds over the weight cutoff for his height, and he had a wife and five dependent children (the limit is three) at home.

The rationale for the Marines to grant multiple waivers for the celebrity recruit remains unclear, but one thing quickly became obvious: Once in uniform, Private Bowe would have to fulfill his duties in the same prescribed manner as would his younger, poorer and non-famous platoon mates. The Marines do not provide exceptions for wannabes who enter their ranks with a measure of wealth and privilege. For someone like Bowe, who detested training for fights and being told what to do as much as he reveled in being champion of the world and living life on his own pampered terms, the strict regimentation required of a Marine – and, even more so, of a Marine recruit – was virtually guaranteed to result in severe culture shock.

Chuck Wepner, the former heavyweight contender best known for his courageous but doomed challenge of WBC/WBA titlist Muhammad Ali on March 24, 1975, as well as being the inspiration for Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky Balboa character, knew better than most what Bowe was getting himself into. Wepner was 17 and a recent high school graduate when he joined the Marines in 1956, serving three years of active duty before mustering out as a corporal.

“The training in boot camp is harder than training for any opponent, ”Wepner, who lasted until the 15th round before being stopped by Ali,told boxing writer Robert Mladinich in 1997, shortly after Bowe left for Parris Island. “Riddick is a world-class athlete and will be in better shape than most of the recruits. I’m sure he can handle the physical aspect, but the mental aspect is the toughest part. The training is built on humiliation and embarrassment. They break you down so they can build you back up as a Marine. When you are a young kid looking for answers it will make a man out of you. But Riddick is pushing 30, a family man with $100 million in the bank. How is he going to take being called `maggot’ instead of `champ’ all day long?”

Bowe wasn’t the first individual to romanticize the notion of a military life, nor will he be the last. One of 13 children raised by Dorothy Bowe in a drug- and crime-infested housing project in the same gritty Brownsville section of Brooklyn, N.Y., that spawned Mike Tyson, he spoke of wanting his mother to see him in his “dress blues at attention” and that “the Marines are the elite and I want to be part of itbefore I get too old.”

To those familiar with what Bowe had to overcome to become the splendid boxer he was during his prime, getting to wear those dress blues was not necessary to qualify as a heroic figure. He refused to yield to the lure of gangs and drugs, and took it as a personal responsibility to walk his mother to and from work to protect her from muggers on the lookout for an easy mark. But not all of his family members were so strong, or so fortunate; he lost a sister, killed by drug dealers, and a brother, killed by AIDS contracted from dirty needles.

When the mocking putdowns arose after Bowe quit the Marines after 11 days, only three of which involved actual training, the fortitude and singularity of purpose he previously had exhibited in rising above his circumstances were largely ignored.

“Parris Island has to be Disney World compared with Brownsville,” Michael Katz, then with the New York Daily News, wrote in defending Bowe as so much more than Gomer Lite. “Don’t even try to compare the mortality rates.”

But while Bowe had the courage to say no to drugs and gangs, he could not always suppress his indulgence in other areas. It was not unusual for him to gain 30 to 40 pounds between fights, and his frequently professed devotion to then-wife Judy and his five kids by her (whose images he had tattooed on his back) notwithstanding, he slept around with the reckless abandon of an alley cat. With the assistance of Florida writer John Greenburg, Bowe’s yet-unpublished memoirs, with the working title of Big Daddy Forever, includes a passage in which he speculates he might have impregnatedas many as 25 women. He also said a family friend paid for six abortions.

Little wonder that Bowe’s manager, Rock Newman, had to repeatedly urgelegendary trainer Eddie Futch, who often threatened to quit and sometimes did, to return to the fighter’s exasperated support team. Then again, Bowe himself always seemed to be looking for the exit. Sure, it was a giddy trip, thrice testing himself against a great warrior like Holyfield and pulling down some serious scratch in the process –at one point Bowe owned 26 cars, including four Rolls-Royces, and 10 houses — as well as having a private audience with the Pope in Vatican City and appearing on The Late Show With David Letterman – but at some point a fighter always has to return to the sweat, pain and monotony of the gym. To his credit, Bowe took time from his opulent and hedonistic ways to serve as a spokesman for Somalia famine relief and as a critic of South Africa’s then-official apartheid policy.

“It’s not like Bowe got money and then started hating the training,” Newman told The Washington Post in 2010. “He always hated it. There was rarely a fight – four, six, eight rounds, whatever – where Bowe didn’t want to quit. I mean, Bowe retired preparing for his second fight.”

Eventually, the lurching starts and screeching halts had to take a toll on any such athlete not named Roberto Duran, and that was never more apparent than in Bowe’s pair of disqualification victories against Golota, who was clearly winning on points in each instance until he sabotaged himself by too often targeting “Big Daddy’s” private parts. Although Bowe officially was 40-1 with 32 knockouts after the second of those matchups, he was a career-high and jiggly 252 pounds for the first, on July 11, 1996, the DQ prompting a half-hour riot in Madison Square Garden, a night which continues to live in pugilistic infamy.

Was it by coincidence or design that Bowe, searching for something he’d either lost or never found, revisited his old Marine Corps fantasy after the second referee-dictated nod over the ball-busting Golota, which took place on Dec. 14, 1996, in Atlantic City’s Boardwalk Hall?

Bowe’s enlistment –the signup deal was for three months of boot camp at Parris Island, six weeks of combat training at Camp LeJeune, N.C., then three years of active and five years inactive Reserve duty in the Washington, D.C. area (Bowe was then living in Fort Washington, Md.) –wasn’t particularly out of the ordinary, other than the fact that most Marine enlistees aren’t granted a slew of waivers prior to holding a press conference to reveal their career pivot.

The Marines didn’t promise Bowe a rose garden prior to his affixing his signature on the enlistment documents. They had him visit Parris Island for a look-around, the better to let him know what he would be in for, and rather than to scare him off, what he saw made him even more enthusiastic. He insisted he would go in with his eyes wide open, and nothing could or would dissuade him.

The first eight days at Parris Island involved mostly paperwork and orientation. But it was that first day of actual training – up at 5 a.m., in bed at 9 p.m., with shouting drill instructors always at high, profane decibel levels – that caused Private Bowe to realize that the lifestyle change he had yearned for was not going to be a good fit. Although neither he nor anyone with the Marines familiar with his situation have spoken at length about particulars of his abbreviated stay, the consensus appears to be that multimillionaires accustomed to freedom of movement are not necessarily the best candidates for a $900.90-a-month job which requires absolute adherence to rules, regulations and a strict code of conduct that is the very essence of esprit de corps. Three days into the nitty-gritty part of his training, Bowe, as well as his friend, Deion Jordan, who was accepted with him under the USMC’s “Buddy Program,” became the first recruits to be released from Platoon 1036, C Company, 1st Recruit Battalion.

“I thought they’d probably give you a hard time for a week or so,” Bowe said. “I didn’t realize that for the 12 weeks you’re in boot camp, somebody was going to be in your face.”

Major Rick Long, then a Marine spokesman at Parris Island, said he had spoken to Bowe about his intention to voluntarily withdraw from training and that he understood, at least to a point, the boxer’s rationale for doing so. “He seemed very genuine in his desire to become a Marine,” Long noted. “However, he decided at this stage of his life that adjusting to the regimented lifestyle was too difficult. It was just a combination of being told when to eat and how fast, when to dress and how fast, and the structured environment. In Marine Corps recruit training, you are constantly supervised and you are on a very rigorous and fast-paced schedule.”

Added Marine Gunnery Sgt. Wiley Tiller: “As an athlete, he had it his way. In the Marines, you don’t have it that way. He would have been totally stripped of anything he ever was. That was probably messing with his manhood. He could have done the physical training, but being told what to do, when to do it, how to do it, that’s not easy for a 29-year-old to handle.”

Newman was of the opinion that family considerations, more so than the Marine way of doing things, likely was the primary reason for Bowe to bail. More than anything, he just might have been homesick.

“For eight years, Riddick’s spent enormous amounts of time away from his wife and family,” Newman reasoned. “The hardest part for Riddick was never in the ring, and it was never the long hours of training. It was always the separation that took place … He hated time away from his family.”

If Newman is correct, what has happened to Bowe in the aftermath of his famously futile flirtation with the Marine Corps devolves from bewildering to tragic. Two months after leaving Parris Island, Bowe abruptly announced his retirement from boxing (he later returned for three winning bouts against C-grade opponents from 2004 to 2008). A year after that, he and Judy separated, he was accused of kidnapping her and the children and forcing them into a car in Charlotte, N.C., and driving them to Maryland. Pleading guilty to a reduced federal charge of interstate domestic violence (for allegedly threatening Judy and the kids with a knife and pepper spray), he was convicted and, following several appeals, sentenced in January 2003 to 18 months in prison. He did the time, plus six months of house arrest, but maintains Judy and the children willingly got into his Lincoln Navigator and that “I never kidnapped anybody.”

Things would go from bad to worse. Bowe filed for bankruptcy in 2005, listing debts in excess of $4 million; his weight, always an issue when he was boxing, swelled to 300 pounds, and during the criminal proceedings against him it was revealed that he underwent neurological tests that indicated he had irreparable frontal lobe damage. Bowe does have slurred speech, but he steadfastly rejects any mental damage stemming from his 45-bout boxing career.

“I feel great,” he told The Post. “Some people tell me I talk funny, but this is the sport I chose and perhaps this is one of the downfalls. It is what it is.”

Bowe, now 49, is remarried – happily, he said, to wife Terri, with whom he has two children — and claims to have exorcised many of the demons that cast dark shadows on his frame of mind before, during and after he did his Marine thing. But, apart from the fact his once-vast fortune is gone, so are those he once welcomed into his inner circle. He no longer has any contact with his onetime Svengali, Newman, or with family members and confidantes who, he said, only wanted to be around him so long as he was paying their way.

“I really don’t have any regrets,” Bowe said in advance of his induction into the IBHOF in June 2015, dismissing some critics’ charges that he deliberately avoided squaring off against Lennox Lewis and Tyson in the pro ranks. “The fact that I fought Evander three times pretty much made up for everything else. I think those other guys (Lewis and Tyson) realize that they couldn’t have done anything better than I did when I fought Holyfield. They couldn’t even have done it as good. (Bowe won two of his three fights with Holyfield, including one by stoppage.)

“If I could change anything, the No. 1 thing is that I wouldn’t have Rock Newman as my manager. I wish I had people around me who had my best interests at heart. I wish I was more into the financial part of the game, that I had paid more attention to what was going on around me. There were meetings and stuff where I needed to be there. I really thought that (Newman) had my back. He didn’t.”

Time has a way of distorting reality to accommodate individual perspective. There are those who maintain that Bowe was unworthy of entering the hallowed halls of the IBHOF, and those who figure his 43-1 career record, with 33 KOs, made him a slam-dunk for election. There also are those who dismiss his 11 days at Parris Island as a cartoonish attempt to regain some form of relevancy, while others credit him for at least taking a few tentative steps toward realization of an inner truth that he long sought, and still lies beyond his grasp.

The real Riddick Bowe remains a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. He is that rare figure who is who he is, but only to himself. For the rest of us, he is who we choose to think of him as being. In their recruiting brochures the Marines promise that “the change is forever,” but one wonders how much change, or how permanent, can be wrought by 11 days in the broad stratosphere of life.

“I just hope Riddick finds whatever it is he’s looking for,” said Mackie Shilstone, the New Orleans-based conditioning expert who had the perplexing task of helping get Bowe ready for some of his most significant bouts. “It always seemed to me he was looking for some alter ego. I think that’s what happened when he went into the Marines. You know that was a form of escapism. He was always trying to escape from, or to, something.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel.

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThomas Hauser’s Literary Notes: Johnny Greaves Tells a Sad Tale

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRolly Romero Upsets Ryan Garcia in the Finale of a Times Square Tripleheader

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoUndercard Results and Recaps from the Inoue-Cardenas Show in Las Vegas

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

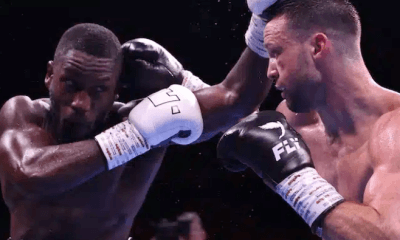

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCanelo Alvarez Upends Dancing Machine William Scull in Saudi Arabia

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBombs Away in Las Vegas where Inoue and Espinoza Scored Smashing Triumphs

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The Good, the Bad, and the (Mostly) Ugly; a Weekend Boxing Recap and More

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoEkow Essuman Upsets Josh Taylor and Moses Itauma Blasts Out Mike Balogun in Glasgow

Pingback: how to open cheapest love bracelet rose

Pingback: fake how much is a cartier love bracelet

Pingback: how much is a cartier love ring replica

Pingback: cartier like love bracelet replica