Argentina

In Boxing, David Beating Goliath is Not Such a Rarity

There is a saying in football that “good and big beats good and little.” That’s usually true, but, as in the case with almost everything in life, there are exceptions to widely accepted rules. If not, why is there also a saying that “good things come in small packages”? The second truism is a common reference to the tiny boxes that hold engagement rings, which can be exorbitantly expensive, but it also might be applicable in some cases to the boxing ring. Inside the ropes, David vs. Goliath matchups can and do happen, with David emerging victorious more often than you might imagine.

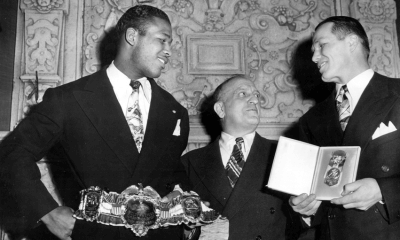

During his bids for and record four reigns as heavyweight champion of the world, Evander Holyfield (inducted earlier this month into the International Boxing Hall of Fame) was often referred to as a “small” heavyweight. The “Real Deal” is 6-2½ and, in his 19 heavyweight championship bouts, his weigh-in poundages ranged from 205 to 221. In fights with a bejeweled big-man belt on the line, Holyfield was the heavier man just once – he came in at 220 to 214 against Chris Byrd – and was the same weight in two others, at 214 for his first matchup against Michael Moorer and 218 for his rematch with Mike Tyson. But despite giving away an average of more than 20 pounds (214.2 to 234.4), Holyfield went 10-7-2, and most would agree that he was jobbed out of a fifth title when he lost a hotly disputed majority decision to 7-foot, 310¾-pound WBA champ Nikolay Valuev on Dec. 20, 2008, in Zurich, Switzerland. Holyfield, who was then 46 years of age, was giving away 9½ inches in height, seven inches in reach and an almost-incomprehensible 90½ pounds to the massive Russian.

Holyfield, of course, is substantially larger than such legendary heavyweight champions as Jack Dempsey and Rocky Marciano, who stood 6-1 and 5-10½, respectively, during eras in which there was no such thing as a cruiserweight division and most world-rated heavyweights were considerably smaller than today’s XXXL-sized equivalents. In his eight heavyweight title bouts, during which he went 6-2 (the two points losses to Gene Tunney) with five knockouts, the “Manassa Mauler” averaged 189.3 pounds to 198.75 for his opponents, but he was actually the heavier man in five of those bouts. Against the much-larger Jess Willard (6-6½, 245) and Luis Angel Firpo (6-2½, 216½), however, Dempsey was a veritable wrecking machine, registering seven first-round knockdowns in each instance en route to blowout victories that embellished his reputation as a giant-killer. For his seven heavyweight title clashes, all wins with six KOs, Marciano averaged 186½ pounds to his opponents’ 192.4, but only once was he outweighed by a double-digit margin (189 to 205), a ninth-round stoppage of England’s Don Cockell in The Rock’s next-to-last fight, on May 16, 1955, in San Francisco.

There have been other relatively small heavyweights who rose above their limited physical dimensions to become elite champions, sub-six-footers Joe Frazier and Mike Tyson coming immediately to mind. And while it was a one-and-done excursion into the land of the large, former middleweight, super middleweight and light heavyweight champion Roy Jones Jr., at 5-11 and 193 pounds, scored a one-sided unanimous decision to dethrone WBA heavyweight titlist John Ruiz, who came in at 6-2 and 226, for their March 1, 2003, bout at the Thomas & Mack Center in Las Vegas.

Two recent events caused me to ponder another age-old question: what counts more, the size of the dog in the fight, or the size of the fight in the dog? One was the excellent heavyweight title bout in which two very large and skilled men, 6-6, 250-pound Anthony Joshua and 6-6, 240¼-pound Wladimir Klitschko, squared off before 90,000 fans in London’s Wembley Stadium on April 29. Joshua retained his IBF championship and added the vacant WBA and IBO belts on an 11th-round TKO in a back-and-forth fight in which longtime former titlist Klitschko went down three times and Joshua once. Both men, obviously, would have been huge heavyweights when Dempsey and Marciano ruled the roost, but it can be argued that, were such a thing possible, they’d be pretty fair light heavyweights or even middleweights if they somehow could be pared down to the requisite specifications.

The other thing that got me to thinking was the International Boxing Hall of Fame induction weekend in Canastota, N.Y., earlier this month in which it again was mentioned that the largest fist-casting ever – 16 inches in circumference! — remains the one taken of onetime heavyweight champ Primo Carnera (pictured), the “Ambling Alp” from Sequals, Italy, who, at 6-5½ and an average of 264½ pounds for his three title bouts, was just as much larger than the guys he faced during his 1930s prime as Valuev was against his opponents six decades later.

Size does count in most sports, but great size without talent only will take someone so far. Wilt Chamberlain was a physical mismatch for almost everyone he went against in the NBA in the 1960s and ’70s, but he didn’t score 100 points in one game, grab 55 rebounds in another and block 27 shots in still another (this before blocked shots became an official NBA statistic) simply because he was 7-1 and a listed 275 pounds. The “Big Dipper” dominated because he had the kind of wondrous athleticism seldom found in anyone so immense; if that were not the case, one of his contemporaries, 7-3 Swede Halbrook, would also be in the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. He isn’t. Nor will anyone confuse 7-2, 225-pound Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the NBA’s all-time leading scorer, with Gheorghe Muresan, who might have been 7-7 and 315 but was a slow-footed plow horse in comparison to Kareem’s elongated thoroughbred.

Statistics are a useful tool in any formula used for equating effectiveness in any athletic arena, but raw numbers alone never tell the whole story. If the Old Testament Book of Samuel offers fact and not fiction, there really was a gigantic Philistine warrior named Goliath who was mortally felled by a stone loosed from the sling of a shepherd boy named David, who would go on to become king of the Israelites. Goliath’s estimated height was measured by something called cubits, with one version listing him at 6-foot-9 (possible) and another at 9-9 (uh, no).

Research which would quantify the separation of boxing’s Wilts and Kareems from its Swedes and Gheorghes became the project which resulted in this story, and it yielded one surprising (to me, at least) result. The largest heavyweight, at least by height, was not, as I had imagined, the hulking Valuev or 7-1 Julius Long, but a Romanian named Gogea Mitu. Although BoxRec.com lists Mitu, who was just 21 when he died on June 22, 1936, as 7-4, other accounts – which probably are exaggerated – list him as anywhere from 7-7 to 8 feet tall. One highly speculative account originating in Europe suggested that Mitu (BoxRec lists his record at 8-2-1, with eight KO victories and five no-contests) might have been descended from an ancient race of giants dating back to – get ready – Goliath himself.

The notion of groups of people genetically predisposed to extreme height is not necessarily outlandish. There are certain African tribes – the Masai in Kenya, Watusi in Rwanda and Hamitic Sudanese – whose male members frequently top out at 7 feet or more. For the most part, they are inordinately slender and nimble, the prime example being the late NBA player Manute Bol, who, at 7-7, matched Muresan as pro basketball’s tallest player but was 90 pounds lighter. However, the most common cause in other parts of the world of a condition known as “giantism,” or hyperplasia of the pituitary gland, is an abnormally high level of human growth hormone. The tallest human to anyone’s irrefutable knowledge, as certified by the Guinness Book of World Records, is the late Robert Wadlow, an llinois native who was 8-foot-11 and 439 pounds when he, as was the case with Mitu, died young (22) on July 15, 1940. An autopsy revealed that if the condition that led to Wadlow’s incredible height had not abated, he would have grown even taller had he lived.

All of which makes Mitu and Valuev the rarest of the rare, even if their motor skills are or were unexceptional for much smaller athletes. Those afflicted with giantism, in effect, become too large to fully control their bodies. Wadlow was barely able to walk at the end of his life, and was able to do so only with the aid of massive braces on his legs. It is not uncommon for living, breathing skyscrapers to suffer from any number of size-related maladies that often result in abbreviated and pain-afflicted lifespans.

If some of what has been said of Mitu is accurate, he was virtually unencumbered by his incredible size for much of his too-brief life. It was said he was highly intelligent, despite little formal education, and his strength was such that, while appearing with the Globus circus of Bucharest, he could bend steel bars with his bare hands. In 1935 an Italian scout, Umberto Lancia, noticed him and offered to sponsor his boxing career. The long-range plan was to take him to America, where stardom or at least bankable oddity status presumably awaited, but he is said to have contracted the flu after opening a window on a Paris-bound train. He fell ill and not long afterward passed away, the cause of death listed as tuberculosis.

Could a 7-4 (or 7-7, or 7-9, or 8-foot) individual have been effective in the ring? Hard to say; most relatively normal-sized opponents could reach his chin only by standing on a stepladder, and for Mitu to reach theirs he would have had to crouch so much he’d literally be bending himself in half. The most obvious parallel in more modern times is Valuev, whose height was exaggerated to 7-2 by American matchmaker Don Elbaum for a couple of appearances in the U.S. When it comes to matters of hype, there apparently can never be too much of a good thing.

In retrospect, Valuev – who posted a 50-2 record with 34 KOs and twice won the WBA heavyweight title – succeeded primarily because of size-related advantages. His punches were ponderous, but when he wrapped smaller men up in bear-hug clinches, it tended to sap their strength as might have been the case were they obliged to wrestle a grizzly bear. But longevity is an attribute not often bestowed on those in Valuev’s exclusive circle, and his two defeats came at the hands of Ruslan Chagaev (6-1, 228¼) and David Haye (6-3, 217), not counting the gift decision he received against Holyfield. Valuev, who turns 44 on Aug 21, retired after his majority-decision loss to Haye on Nov. 10, 2009, was shortly thereafter diagnosed as having severe bone and joint problems, which necessitated two operations.

Other extremely large heavyweights comprise a hit-and-miss group. Some have enjoyed or did enjoy a measure of prosperity that owed, at least in part, to their gargantuan size. Some were merely curiosity items, tall trees to be chopped down by small but skilled lumberjacks. The list includes:

*Mike “The Giant” White (26-13-1, 19 KOs). Now 60, the 6-10 White was 275 pounds when he lost a 10-round unanimous decision to Michael Moorer on Feb. 1, 1992, ending a streak of 26 consecutive knockout victories for future heavyweight champ Moorer. But that is not the highlight of White’s career; his fourth-round stoppage of another future heavyweight titlist, Buster Douglas, on Dec. 17, 1983, is.

*Primo Carnera (88-14, 71 KOs). Had he come along today, Carnera, who was 60 when he died on June 29, 1967, would not be considered to be such a behemoth. Was he a mythic figure who was made into something more than what he really was by a hype machine always set on high? Evidence would seem to support that. Carnera’s rise to fame was told, albeit with different names (the thinly disguised part of Carnera was played by actor Mike Lane in the pivotal role of Toro Moreno) in the 1956 film The Harder They Fall, was authored by Budd Schulberg and is most notable today as being the last film for Humphrey Bogart, who portrayed an unscrupulous press agent. Carnera weighed 52¾ pounds more than Jack Sharkey when he won the heavyweight title, and he was 84 pounds more than former light heavyweight champ Tommy Loughran for his sole successful defense, by 15-round decision. His second defense, in which he outweighed Max Baer by 59½ pounds, saw him floored 10 times and beaten bloody in losing via 11th-round stoppage on June 14, 1934.

*Julius Long (18-20, 14 KOs). At 7-1 and as much as 315¾ for one fight, “The Towering Inferno” was rarely more than a spark. For his July 2, 2011, bout with Johnathan Banks, Long held advantages of 10 inches in height and 91 pounds. He still lost a 10-round unanimous decision.

*Tyson Fury (25-0, 18 KOs). At 6-9 and as much as 274 at his heaviest (a fourth-round stoppage of Joey Abell on Feb. 15, 2014), Fury still has a chance, at 28, to get his act together. He was briefly the toast of boxing when he outpointed Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA/IBF/WBO/IBO titles on Nov. 28, 2015. But Fury has not fought since, and his championships were stripped after revelations of his epic cocaine binge and struggles with depression went public.

*Eric “Butterbean” Esch (77-10-4, 58 KOs). Now 50, the erstwhile “King of the Four-Rounders” can only look up to all of the aforementioned fighters, but he earns a special mention here for also being the Widest of the Wide, at a scale-busting 426½ pounds for his final boxing match, in which he retired with shoulder pain after the second round against Kirk Lawton on June 29, 2013.

*Andre Roussimoff. The pro rassler best known as Andre the Giant never laced up a pair of boxing gloves, but he did take on onetime heavyweight contender Chuck Wepner in a mixed-discipline novelty bout on June 25, 1976, in New York’s Shea Stadium. Wepner was no midget at 6-5 and 225 or so pounds, but he appeared to be little more than a rag doll against Andre, who was billed as 7-4 (he likely was a few inches shorter) and 540 pounds. The “fight” ended in the third round when Andre picked up Wepner and tossed him over the ring ropes into some unfortunate fans with premium seats. Say what you want about Andre – who was 46 when he died of heart disease on Jan. 27, 1993 – but he had some moves to go along with all that bulk. If you think Valuev wore guys down in clinches, can you imagine their being enveloped by the tree-trunk arms of Andre the Giant? And while it might have been a publicity stunt, the Washington Redskins, then coached by George Allen, brought Andre to their training facility in 1975 with the idea of signing him as a defensive tackle. There is a famous photo of Andre holding quarterback Joe Theismann on his shoulder like a pirate with a pet parrot.

– – –

Primo Carnera photograph undated but circa 1933. Many photos of Carnera were doctored to make him look bigger.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-30-

Argentina

The BWAA Shames Veteran Referee Laurence Cole and Two Nebraska Judges

In an unprecedented development, the Boxing Writers Association of America has started a “watch list” to lift the curtain on ring officials who have “screwed up.” Veteran Texas referee Laurence Cole and Nebraska judges Mike Contreras and Jeff Sinnett have the unwelcome distinction of being the first “honorees.”

“Boxing is a sport where judges and referees are rarely held accountable for poor performances that unfairly change the course of a fighter’s career and, in some instances, endanger lives,” says the BWAA in a preamble to the new feature. Hence the watch list, which is designed to “call attention to ‘egregious’ errors in scoring by judges and unacceptable conduct by referees.”

Contreras and Sinnett, residents of Omaha, were singled out for their scorecards in the match between lightweights Thomas Mattice and Zhora Hamazaryan, an eight round contest staged at the WinnaVegas Casino in Sloan, Iowa on July 20. They both scored the fight 76-75 for Mattice, enabling the Ohio fighter to keep his undefeated record intact via a split decision.

Although Mattice vs. Hamazaryan was a supporting bout, it aired live on ShoBox. Analyst Steve Farhood, who was been with ShoBox since the inception of the series in 2001, called it one of the worst decisions he had ever seen. Lead announcer Barry Tompkins went further, calling it the worst decision he has seen in his 40 years of covering the sport.

Laurence Cole (pictured alongside his father) was singled out for his behavior as the third man in the ring for the fight between Regis Prograis and Juan Jose Velasco at the Lakefront Arena in New Orleans on July 14. The bout was televised live on ESPN.

In his rationale for calling out Cole, BWAA prexy Joseph Santoliquito leaned heavily on Thomas Hauser’s critique of Cole’s performance in The Sweet Science. “Velasco fought courageously and as well as he could,” noted Hauser. “But at the end of round seven he was a thoroughly beaten fighter.”

His chief second bullied him into coming out for another round. Forty-five seconds into round eight, after being knocked down for a third time, Velasco spit out his mouthpiece and indicated to Cole that he was finished. But Cole insisted that the match continue and then, after another knockdown that he ruled a slip, let it continue for another 35 seconds before Velasco’s corner mercifully threw in the towel.

Controversy has dogged Laurence Cole for well over a decade.

Cole was the third man in the ring for the Nov. 25, 2006 bout in Hildalgo, Texas, between Juan Manuel Marquez and Jimrex Jaca. In the fifth round, Marquez sustained a cut on his forehead from an accidental head butt. In round eight, another accidental head butt widened and deepened the gash. As Marquez was being examined by the ring doctor, Cole informed Marquez that he was ahead on the scorecards, volunteering this information while holding his hand over his HBO wireless mike. The inference was that Marquez was free to quit right then without tarnishing his record. (Marquez elected to continue and stopped Jaca in the next round.)

This was improper. For this indiscretion, Cole was prohibited from working a significant fight in Texas for the next six months.

More recently, Cole worked the 2014 fight between Vasyl Lomachenko and Orlando Salido at the San Antonio Alamodome. During the fight, Salido made a mockery of the Queensberry rules for which he received no point deductions and only one warning. Cole’s performance, said Matt McGrain, was “astonishingly bad,” an opinion echoed by many other boxing writers. And one could site numerous other incidents where Cole’s performance came under scrutiny.

Laurence Cole is the son of Richard “Dickie” Cole. The elder Cole, now 87 years old, served 21 years as head of the Texas Department of Combat Sports Regulation before stepping down on April 30, 2014. At various times during his tenure, Dickie Cole held high executive posts with the World Boxing Council and North American Boxing Federation. He was the first and only inductee into the inaugural class of the Texas Boxing Hall of Fame, an organization founded by El Paso promoter Lester Bedford in 2015.

From an administrative standpoint, boxing in Texas during the reign of Dickie Cole was frequently described in terms befitting a banana republic. Whenever there was a big fight in the Lone Star State, his son was the favorite to draw the coveted refereeing assignment.

Boxing is a sideline for Laurence Cole who runs an independent insurance agency in Dallas. By law in Texas (and in most other states), a boxing promoter must purchase insurance to cover medical costs in the event that one or more of the fighters on his show is seriously injured. Cole’s agency is purportedly in the top two nationally in writing these policies. Make of that what you will.

Complaints of ineptitude, says the WBAA, will be evaluated by a “rotating committee of select BWAA members and respected boxing experts.” In subsequent years, says the press release, the watch list will be published quarterly in the months of April, August, and December (must be the new math).

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

Argentina

Popo vs. “La Hiena”: Blast From the Past – Episode Two

When WBA/WBO super featherweight champion Acelino “Popo” Freitas met Jorge Rodrigo “Il Hiena” Barrios in Miami on August 8, 2003, there was more on the line than just the titles. This was a roughhousing 39-1-1 Argentinian fighting an equally tough 33-0 Brazilian. The crowd was divided between Brazilian fans and those from Argentina. To them this was a Mega-Fight; this was BIG.

When Acelino Freitas turned professional in 1995, he streaked from the gate with 29 straight KOs, one of the longest knockout win streaks in boxing history. He was fan-friendly and idolized in Brazil. Barrios turned professional in 1996 and went 14-0 before a DQ loss after which he went 25-0-1 with 1 no decision.

The Fight

The wild swinging “Hyena” literally turned into one as he attacked from the beginning and did not let up until the last second of the eleventh round. Barrios wanted to turn the fight into a street fight and was reasonably successful with that strategy. It became a case of brawler vs. boxer/puncher and when the brawler caught the more athletic Popo—who could slip and duck skillfully—and decked him with a straight left in the eighth, the title suddenly was up for grabs.

The Brazilian fans urged their hero on but to no avail as Barrios rendered a pure beat down on Popo during virtually the entirety of the 11th round—one of the most exciting in boxing history. Freitas went down early from a straight right. He was hurt, and at this point it looked like it might be over. Barrios was like a madman pounding Popo with a variety of wild shots, but with exactly one half of one second to go before the bell ending the round, Freitas caught La Hiena with a monster right hand that caused the Hyena to do the South American version of the chicken dance before he went down with his face horribly bloodied. When he got up, he had no idea where he was but his corner worked furiously to get him ready for the final round. All he had to do was hang in there and the title would change hands on points.

The anonymous architect of “In Boxing We Trust,” a web site that went dormant in 2010, wrote this description:

“Near the end of round 11, about a milli-second before the bell rang, Freitas landed a ROCK HARD right hand shot flush on Barrios’ chin. Barrios stood dazed for a moment, frozen in time, and then down he went, WOW WOW WOW!!!! Barrios got up at the count of 4, he didn’t know where he was as he looked around towards the crowd like a kid separated from his family at a theme park, but Barrios turned to the ref at the count of 8 and signaled that he was okay, SAVED BY THE BELL. It was panic time in the Barrios corner, as the blood continued to flow like lava, and he was bleeding from his ear (due to a ruptured ear drum). In the beginning of round 12, Freitas was able to score an early knockdown, and as Barrios stood up on wobbly legs and Freitas went straight at him and with a couple more shots, Barrios was clearly in bad shape and badly discombobulated and the fight was stopped. Freitas had won a TKO victory in round 12, amazing!!!!”

Later, Freitas tarnished his image with a “No Mas” against Diego Corrales, but he had gone down three times and knew there was no way out. He went on to claim the WBO world lightweight title with a split decision over Zahir Raheem, but that fight was a snoozefest and he lost the title in his first defense against Juan “Baby Bull” Diaz.

Freitas looked out of shape coming in to the Diaz fight and that proved to be the case as he was so gassed at the end of the eighth round that he quit on his stool. This was yet another shocker, but others (including Kostya Tszyu, Mike Tyson, Oscar De La Hoya and even Ali) had done so and the criticism this time seemed disproportionate.

Popo had grown old. It happens. Yet, against Barrios, he had proven without a doubt that he possessed the heart of a warrior.

The Brazilian boxing hero retired in 2007, but came back in 2012 and schooled and KOd the cocky Michael “The Brazilian Rocky” Oliveira. He won another fight in 2015 and though by now he was visibly paunchy, he still managed to go 10 rounds to beat Gabriel Martinez in 2017 with occasional flashes of his old explosive volleys. These later wins, though against lower level opposition, somewhat softened the memories of the Corrales and Diaz fights, both of which this writer attended at the Foxwoods Resort in Mashantucket, Connecticut. They would be his only defeats in 43 pro bouts.

Like Manny Pacquiao, Freitas had a difficult childhood but was determined to make a better life for himself and his family. And, like Manny, he did and he also pursued a career in politics. Whether he makes it into the Hall will depend on how much a ‘No Mas’ can count against one, but he warrants serious consideration when he becomes eligible.

As for the Hyena, on April 8, 2005, he won the WBO junior lightweight title with a fourth round stoppage of undefeated but overweight Mike Anchondo. In January 2010 he was involved in a hit and run accident in which a 20-year-old pregnant woman was killed. On April 4, 2012 Barrios was declared guilty of culpable homicide and sentenced to four years in prison. He served 27 months and never fought again, retiring with a record of 50-4-1.

Ted Sares is one of the oldest active full power lifters in the world. A member of Ring 10, and Ring 4’s Boxing Hall of Fame, he was recently cited by Hannibal Boxing as one of three “Must-Read” boxing writers.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

Argentina

The Avila Perspective Chapter 6: Munguia, Cruiserweights and Pacman

Adjoining states in the west host a number of boxing cards including a world title contest that features a newcomer who, before knocking out a world champion, was erroneously categorized by a Nevada official as unworthy of a title challenge.

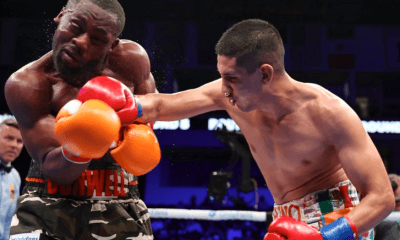

Welcome to the world of Mexico’s Jaime Munguia (29-0, 25 KOs) the WBO super welterweight world titlist who meets England’s Liam Smith (26-1-1, 14 KOs) at the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas on Saturday, July 21. HBO will televise

Back in April when middleweight titan Gennady “GGG” Golovkin was seeking an opponent to replace Saul “Canelo” Alvarez who was facing suspension for performance enhancement drug use, it was the 21-year-old from Tijuana who volunteered his services for a May 5th date in Las Vegas.

Bob Bennett, the Executive Director for Nevada State Athletic Commission, denied allowing Munguia an opportunity to fight Golovkin for the middleweight titles. Bennett claimed that the slender Mexican fighter had not proven worthy of contesting for the championship though the tall Mexican wielded an undefeated record of 28 wins with 24 coming by knockout.

To be fair, Bennett has seen many fighters in the past with undefeated records who were not up to challenges, especially against the likes of Golovkin. But on the other hand, how can an official involved in prizefighting deny any fighter the right to make a million dollar payday if both parties are willing?

That is the bigger question.

Munguia stopped by Los Angeles to meet with the media last week and spoke about Bennett and his upcoming first world title defense. He admitted to being in the middle of a whirlwind that is spinning beyond his expectations. But he likes it.

“I’ve never won any kind of award before in my life,” said Munguia at the Westside Boxing Club in the western portion of Los Angeles. “I’ve always wanted to be a world champion since I was old enough to fight.”

When asked how he felt about Nevada’s denying him an attempt to fight Golovkin, a wide grin appeared on the Mexican youngster.

“I would like to thank him,” said Munguia about Bennett’s refusal to allow him to fight Golovkin. “Everything happens for a reason.”

That reason is clear now.

Two months ago Munguia put on a frightening display of raw power in knocking down then WBO super welterweight titlist Sadam Ali numerous times in front of New York fans. It reminded me of George Foreman’s obliteration of Joe Frazier back in the 1970s. World champions are not supposed get battered like that but when someone packs that kind of power those can be the terrifying results.

Still beaming over his newfound recognition, Munguia has grand plans for his future including challenging all of the other champions in his weight category and the next weight division.

“I want to be a great champion,” said Munguia. “I want to make history.”

The first step toward history begins on Saturday when he faces former world champion Smith who was dethroned by another Mexican named Canelo.

Cruiserweight championship

It’s not getting a large amount of attention in my neighborhood but this unification clash between WBA and IBF cruiserweight titlist Murat Gassiev (26-0, 19 KOs) and WBC and WBO cruiserweight titlist Oleksandr Usyk (14-0, 11 KOs) has historic ramifications tagged all over it.

The first time I ever saw Russia’s 24-year-old Gassiev was three years ago when he made his American debut at the Quiet Cannon in Montebello. It’s a small venue near East L.A. and the fight was attended by numerous boxing celebrities such as James “Lights Out” Toney, Mauricio “El Maestro” Herrera and Gennady “GGG” Golovkin. One entire section was filled by Russian supporters and Gassiev did not disappoint in winning by stoppage that night. His opponent hung on for dear life.

Ukraine’s Usyk, 31, made his American debut in late 2016 on a Golden Boy Promotions card that staged boxing great Bernard Hopkins’ final prizefight. That night the cruiserweight southpaw Usyk bored audiences with his slap happy style until lowering the boom on South Africa’s Thabiso Mchunu in round nine at the Inglewood Forum. The sudden result stunned the audience.

Now it’s Gassiev versus Usyk and four world titles are at stake. The unification fight takes place in Moscow, Russia and will be streamed via Klowd TV at 12 p.m. PT/ 3 p.m. ET.

Seldom are cruiserweight matchups as enticing to watch as this one.

Another Look

A couple of significant fights took place last weekend, but Manny Pacquiao’s knockout win over Lucas Matthysse for the WBO welterweight world title heads the list.

Neither fighter looked good in their fight in Malaysia but when Pacquiao floored Matthysse several times during the fight, it raised some red flags.

The last time Pacquiao knocked out a welterweight was in 2009 against Miguel Cotto in Las Vegas. Since then he had not stopped an opponent. What changed?

In this age of PEDs there was no mention of testing for the Pacquiao/Matthysse fight. For the curiosity of the media and the fans, someone should come forward with proof of testing. Otherwise any future fights for the Philippine great will not be forthcoming.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 322: Super Welterweight Week in SoCal

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoGabriela Fundora KOs Marilyn Badillo and Perez Upsets Conwell in Oceanside

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks ago‘Krusher’ Kovalev Exits on a Winning Note: TKOs Artur Mann in his ‘Farewell Fight’

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFloyd Mayweather has Another Phenom and his name is Curmel Moton

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: The First Boxing Writers Assoc. of America Dinner Was Quite the Shindig

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 323: Benn vs Eubank Family Feud and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoChris Eubank Jr Outlasts Conor Benn at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoJorge Garcia is the TSS Fighter of the Month for April