Featured Articles

A New Book on Jack Dempsey is Worth a Look

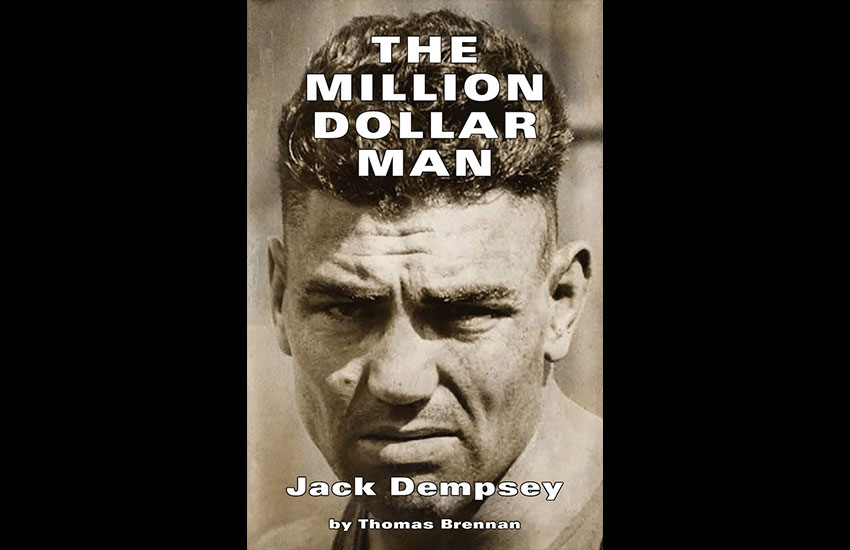

But certain new arrivals sometimes are promptly moved to the front of the line, which was the case with The Million Dollar Man: Jack Dempsey

My personal library contains hundreds of books, dozens of which this voracious reader has yet to get around to. There is, after all, only so much time in any given day to spend large chunks of it curling up with a mystery novel or biography of a notable person. But certain new arrivals sometimes are promptly moved to the front of the line, which was the case with The Million Dollar Man: Jack Dempsey, authored by Thomas Brennan, which came in the mail recently with a written request from the publisher (Regent Press of Berkeley, CA) that I kindly review it for the edification of would-be purchasers.

Well, OK. The life and times of William Harrison Dempsey – the “Manassa Mauler’s” birth name – is of such import that it has been covered at length in previous literary ventures, including Round by Round, Dempsey’s autobiography written in conjunction with contributor Myron M. Stearns, and Dempsey, again written by the great man himself with input from Jack’s stepdaughter, Barbara Piatelli Dempsey. There aren’t wide swaths of untilled soil in The Million Dollar Man (a reference to Dempsey being the attraction in the first five fights to generate million-dollar live gates), and some of Brennan’s prose tends to be excessively flowery, as was frequently the case with such legendary early-20th-century sports writers as Paul Gallico, Damon Runyan and Grantland Rice, inflatable garden slide whose ruminations on the most compelling sports superstar (along with New York Yankees slugger Babe Ruth) of the Roaring ’20s include descriptions of the punches Jack delivered as “lusty cracks” and “wallops.” But a bit of excess is perhaps allowable if the lead character is larger than life, and the nearly century-old past from which Dempsey emerged serves as prologue. Bits and pieces of the enthralling road traveled by Dempsey were played out, in one form or another, by such later heroes of the ring (or anti-heroes, depending on one’s point of view) as Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier and Mike Tyson.

I admittedly remain a moth drawn to Dempsey’s flame because of his connection, however tenuous, to my all-time favorite fighter, a quite unrenowned welterweight whose professional record was 4-1-1, with just one victory by knockout. But Jack Fernandez, like Jack Dempsey, came into this world with a different birth name. He departed this mortal coil at age 74 as Bernard J. Fernandez Sr. on March 4, 1994, my father’s nickname having been conferred upon him as an amateur by someone who compared his boxing style – crouching, bobbing and weaving, always coming forward – to that of the infinitely more celebrated former heavyweight champion. Some yellowed clippings of Dad’s fighting days variously describe him as a “left hook specialist” and a “wild-hooking slugger.” I wish I had video of him in action, but I do have a poster from 1944 in which his name appears right under that of main-eventer Archie Moore.

But I digress. Gallico once described Dempsey (and this particular passage is not in Brennan’s book) thusly: “His weaving, shuffling style of approach suggested the stalking of a jungle animal. He had a smoldering truculence on his face and hatred in his eyes.” Brennan supports the notion of Dempsey as predator, claiming that he “singlehandedly brought shock and awe to the sport of boxing like no one before or since … The Manassa Mauler backed down to no man in the ring. He stalked his opponents much the same way a tiger stalks his prey.”

Many of the better fighters from every era arise from abject poverty, and Dempsey was no exception. He was the ninth of Hyrum and Celia Dempsey’s 13 children, and perhaps the only one predestined to follow a particular career path. Before Jack was born, his mother had read and re-read a book given to her by an old peddler, Life of a 19th Century Gladiator, supposedly authored by John L. Sullivan but no doubt assisted in no small part by a ghost writer. Celia told Jack years later that, before he was born, she wanted her next male child to be the next John L. Sullivan.

In truth, Harry – which is what the rest of the family, which relocated often in search of better financial opportunities, called him – was preceded as a boxer by older brother Bernie, who for reasons unstated billed himself as Jack Dempsey. But Bernie had a liability, a glass jaw that precluded him from ever making it big as a fighter. In the hope of avoiding the pugilistic fate that had befallen Bernie, Harry – then going by the nom de guerre of “Kid Blackie” in mostly unsanctioned (and unrecorded for historical purposes) bouts – chewed rosin gum to strengthen his jaw muscles and soaked his face in beef brine to toughen his skin and make it less susceptible to cuts.

“Who knows how many fights I had between 1911 and 1916?” the former Kid Blackie said years later, after he had officially switched his ring (and legal) name to Jack Dempsey in tribute to the retired Bernie. “The record books don’t contain them, and I couldn’t name the number or identify all the faces today if my life depended on it. I’d guess a hundred. But that’s still a guess. Whatever the number was, it wasn’t enough to support me. To fill the gaps and my belly, I was a dishwasher, a miner or anything else you could dig up in Nevada, Utah, Colorado and Idaho – I dug potatoes and beets, punched cattle, shined shoes and was a porter in the Hotel Utah in Salt Lake City.”

In search of more and better-paying fights, and to capture the attention of nationally influential sports writers, Dempsey relocated to New York City. He did have some spot success – Damon Runyon was the first columnist to refer to him as the “Manassa Mauler,” a reference to the Colorado mining town in which he was born, and a sobriquet which eventually took root with the public – but the constant struggle for recognition wore on him and he moved back to his comfort zone out west.

Except that Dempsey’s comfort zone wasn’t any more comforting than New York. He was still scuffling along, considering quitting the ring, when a fortuitous turn of events – a barroom brawl – essentially turned his life around. He was having a drink in a saloon in Oakland, Calif., when he noticed several men attacking another bar patron, who was by far getting the worst of it. Jack went to the aid of the customer being pummeled, driving off the assailants. The guy he saved from taking a more severe thrashing was Jack “Doc” Kearns, a boxing manager, who figured anyone that handy with his fists had to have boxing potential. He immediately offered to take his accidental savior under his wing.

Kearns might have been many things, not all of them good – Dempsey later claimed Kearns had shortchanged him on several purses, and the two had a bitter falling-out that led to Kearns filing a lawsuit against his onetime meal ticket – but their association soon began to pay major dividends, with Jack rising to the position of the top-ranked heavyweight contender to champion Jess Willard after he starched the previous No. 1, Fred Fulton, in a mere 18 seconds on July 27, 1918.

But Willard, nicknamed “The Pottawatomie Giant” (for his hometown of Pottawatomie, Kan.) at 6-6½ and 245 pounds, dismissed Dempsey as too small to pose much of a threat. Kearns and Dempsey were obliged to embark on a nationwide tour in which Dempsey registered five consecutive first-round knockouts in early 1919 while constantly chirping for Willard to come out of hiding and face him. Given the immense size difference – the 6-foot-1 Dempsey was scarcely 180 pounds then – there was some concern that Willard might lethally dispose of the mouthy challenger, as he had six years earlier when another opponent, John “Bull” Young, died of a brain hemorrhage a day after he was knocked unconscious. Willard even asked Kearns to provide written assurance that no attempt would be made to file charges if he did unto Dempsey what he had done to Young.

America was still not that far from its frontier days when the Willard-Dempsey fight finally took place on July 4, 1919, in Toledo, Ohio. Legendary Old West lawmen Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp, serving as human metal detectors, were charged with the responsibility of collecting guns and knives from armed fans before they could enter the outrageously hot stadium.

Willard was correct, in a sense; a slaughter did indeed take place. But it was not Dempsey’s health and well-being that were in jeopardy, it was Willard’s after the ferocious aspirant to the title – perhaps spurred on by the knowledge that Kearns had bet $10,000 of their money (at 10-to-1 odds) on him to win by first-round knockout – beat the champion bloody in the process of flooring him seven times in that opening stanza. Willard was counted out by referee Ollie Pecord after the last of those knockdowns, but the bell sounded just prior to the toll of 10, obliging the battered Willard to submit himself to more punishment while Kearns and Dempsey missed out by a couple of ticks on $100,000 additional income on the wager. Willard did not come out for the fourth round, having gone down twice more in round three.

Handsome in a rugged, outdoors kind of way with his chiseled physique, jet-black hair, bushy eyebrows, piercing eyes and mesmerizing air of malevolence, Dempsey, already on the way there, was instantly confirmed as the USA’s new king of the ring following his beatdown of the favored Willard. Damon Runyon, ever the wordsmith, wrote that Willard’s submission came “just as the bell was about to toss him into the fourth round of a mangling at the paws of Jack Dempsey, the young mountain lion in human form, from the Sangre de Cristo Hills of Colorado.”

But those placed upon a pedestal learn fast that the fall from grace can be swift and damaging. Dempsey was soon thereafter denounced as a “slacker” after reporters learned he had not served in the U.S. military during World War I, prompting Grantland Rice of the New York Tribune to temper his praise of the new titlist’s ferociousness inside the ropes with his presumed lack of patriotism outside of them.

“Let us have no illusions about our new heavyweight champion,” Rice wrote. “He is a marvel in the ring, the greatest hitting machine even the old-timers have ever seen. But he isn’t the world’s champion fighter. Not by a margin of 50,000 men who either stood or were even ready to stand the test of cold steel and exploding shell for anything from six cents to a dollar a day.”

By and by, Dempsey’s undeniable charisma and crowd-pleasing savagery in plying his trade won over that portion of a nation, and the world, that would have preferred him to have included a Sergeant York chapter in his thickening book of pugilistic accomplishments. During a trip to Europe he literally had to fight off female admirers, and his popularity soared to a point that an envious Babe Ruth reportedly considered taking up boxing before coming to his senses and sticking with baseball.

A four-round destruction of France’s Georges Carpentier was the first of five fights involving Dempsey to have generated million-dollar live gates, to be followed by those against Luis Angel Firpo, Jack Sharkey and the two losing matchups with Gene Tunney, his stylistic opposite.

Where Dempsey had always fought to win as quickly and emphatically as possible, a boiling pot of explosive energy always on the verge of eruption, Tunney, a former Marine, was a scholarly type who, despite a decent KO percentage, considered boxing to be something of a sweaty but nonetheless intellectual pursuit.

“I am here to train for a boxing contest, not a fight,” Tunney said before the rematch with Dempsey on Sept. 22, 1927, the notorious “Long Count” bout. “I don’t like fighting. Never did. But I’m free to admit that I like boxing.”

Such comments by Tunney did not set well with fans that preferred Dempsey’s familiar go-for-the-jugular aggression. Gallico claimed that Tunney’s image was that of a “priggish, snobbish, bookish fellow, too proud to associate with common prizefighters.”

By the time an aging Dempsey, by now accustomed to taking long breaks between fights, entered into his fire-and-ice meetings with Tunney, however, his internal blaze was already set to low flame. Even a jungle cat might be capable of fighting mad only so long. Even before his epic slugfest with the much larger Firpo, in which the Argentine went down nine times and Dempsey twice in two rounds, the champion spoke wistfully of the changes brought about when the desperation of poverty is replaced by the comfort of wealth and privilege.

“Maybe I can’t take as much now as I took then,” Dempsey said. “It’s much easier you know and more fun fighting your way to the top and defending it. Being champion isn’t as great as it seemed before I was champion. I have more money and softer living, but there are more worries and troubles and cares than I ever dreamed of before. The glory and even the money don’t mean as much as they did in the days when you belonged only to yourself – not the public.”

Now, regarding those parallels between Dempsey and those who would later fill his role and his shoes as elite heavyweight champions. That crouching, swarming, no-reverse-gear, left-hook-heavy attack? “Smokin” Joe Frazier fits the bill.

What about the controversy and loss of fan support that arose from Dempsey’s lack of military service during wartime? Sounds a lot like Muhammad Ali staying on the sidelines during Vietnam, doesn’t it?

Dempsey’s bitter split with his longtime manager, Kearns? How about the unpleasant professional separation of Mike Tyson from his disliked co-manager Bill Cayton after the two father figures in Iron Mike’s life, Cus D’Amato and Jimmy Jacobs, passed away?

Nor were Dempsey’s marital difficulties lastingly unique. His first wife, Maxine, was a prostitute 16 years his senior. His second wife, Estelle Taylor, was a stunningly beautiful model and actress who detested her husband’s boxing friends and considered them to be low-class and beneath her station. Tyson’s first wife, Robin Givens, apparently didn’t much care for anything about him except for the lavish lifestyle he was able to provide her.

Fortunately for Dempsey, his post-boxing life was as rich and fulfilling, in its own way, as had been his ring career. Not only did he enjoy a long and successful run as a New York restaurateur, but he served in the Coast Guard during World War II and was part of the American assault on Okinawa in 1945, when he was 49. Doing so mollified whatever holdovers were still resentful about his non-participation in the so-called war to end all wars.

If there is a lingering knock on Dempsey, it is the lack of black opponents on his otherwise sterling resume. He never did swap punches with such highly capable men of color as Sam Langford and Harry Wills, a taint that still clings in part to his legacy and is a shameful reminder of the bigotry prevalent in America in the early 20th century. It should be noted, however, that Dempsey urged promoter Tex Rickard to arrange a fight with Wills, but Rickard either was unwilling or unable to do so because of the tense racial politics of that time. Too many managers and promoters remembered the race riots that erupted throughout the country after Jack Johnson, a black man with swagger, conquered James J. Jeffries in 1910.

Dempsey was 87 when he died on May 31, 1983, but he remains a pivotal figure in the first golden age of American sports in the 1920s, a heyday also marked by Ruth, football’s Red Grange, golf’s Bobby Jones and tennis’ Bill Tilden. If you think Tom Brady and LeBron James are big deals today, beamed into your living room or den in high-definition color with regularity by the miracle of satellite communications, imagine yourself and a dozen friends hunched around an upright radio, listening to an excited announcer describe the majesty of a Ruth home run or a Dempsey knockout.

The very inaccessibility of such athletes in the 1920s stamped them as wondrous, almost mystical individuals. Were they mortal men, hewn of flesh and bone? Or did some elixir of the gods course through their veins, enabling them to extend the boundaries of athletic capability to limits once thought unimaginable?

The Million Dollar Man might not be a long (262 pages) or classic read, but its subject matter will grab anyone who wants to know more about one of the fight game’s most enduring and cherished legends. It might make a nice Christmas present for any fight fan willing to open an important portal to boxing’s past.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles1 day ago

Featured Articles1 day agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden