Asia & Oceania

The Fifty Greatest Bantamweights of All Time: Part Three, 30-21

From the dusty streets of Algeria to old school British cobbles, to the heartland of the American dream and back again, Part 3 of the Fifty Greatest Bantamweights of all time continues

From the dusty streets of Algeria to old school British cobbles, to the heartland of the American dream and back again, Part 3 of the Fifty Greatest Bantamweights of all time continues the international flavor of this list, but always, always, we return to those familiar back allies in Mexico.

If Mexican fighters remain the beating heart of boxing then bantamweight is the blood that pumps it. What it is that makes Mexican men weighing in at the magical 118lbs so dangerous to the rest of humanity? I cannot tell, but let me just say this:

Viva Mexico.

#30 – Alphonse Halimi (1955-1964)

Alphonse Halimi found his way from the most disgusting poverty imaginable, homeless on the streets of war-torn Algeria, to a world championship boxing ring, the adornments sewn upon his trunks as he fought for the title those same adornments he had sewn to his training trunks as a boy, bent to the light of some cheap candle. He was born for the ring.

It is probable that when top contender Billy Peacock was tempted out to Paris for a payday against a twenty-something with a 10-0 record he was looking forwards to picking up some easy money and seeing the sights. But Halimi was a veteran of a perhaps as many as a hundred amateur contests before he even arrived in France and of numerous more nefarious unrecorded affairs from the years before that. Halimi did not even allow his youth to crowd his work; he out-thought, out-boxed and out-maneuvered his supposedly more experienced opponent for a clear decision, oblivious to the booing that greeted the slow pace.

He defeated a second top ten contender, Tony Campo, later that year, and then, apparently, he was ready for world champion Mario D’Agata. Those curious as to D’Agata’s qualities can review Part 1; Halimi ripped the title from him over fifteen rounds, dominating him throughout and dropping as few as two rounds by some accounts.

Halimi’s title reign was short, but it is always impressive to me when the new champion, having deposed the old, immediately travels to take on the division’s number one contender. This is what Halimi did, arriving on American shores for the first time. Still inexperienced by championship standards, he shifted to boxing on his toes in the championship rounds to out-point the respected Mexican Raul Macias.

After stopping the ranked Al Asuncion, Halimi ran into a Mexican he couldn’t better, the superb Jose Becerra, but he would go on to add quality to his resume while chasing what was a then hotly contested European title, swapping a pair with Piero Rollo and defeating Freddie Gilroy.

#29 – Jose Becerra (1953-1962)

One of the less championed Mexican bantamweight kings (and to be fair, it’s a crowded bar), Jose Becerra did something neither Ruben Olivares nor Carlos Zarate could manage, retiring the undefeated bantamweight champion of the world, albeit after suffering a knockout loss up at featherweight.

He took the title from the wonderful Alphonse Halimi in 1959, dropping him twice in the eighth and forcing an end to the fight by technical knockout. Halimi had never been stopped by punches and there was doubt enough that a rematch was made in which Becerra turned the trick once more, this time in nine.

In the first fight, Halimi had dominated cleanly and clearly early, combining sapping pressure with a withering and varied body attack, marginally behind at the time of the stoppage. In the second, perhaps Becerra’s masterpiece, the Mexican got his sweeping offense going early, finding rough lodgings for all three punches in his mixed combinations, meanwhile popping off that stiff but glancing jab, upsetting Halimi’s rhythm. Climbing from the canvas in the second, Becerra seized control and did not relent until a patented right hook from a square stance – patented, I think, in order to counter Halimi’s body attack – marked the beginning of the end in the ninth: a triple left-hook, double uppercut and an absolute peach of a right hand finished it moments later. It was probably the finest minute of Becerra’s career.

Becerra staged only one defense of his title, harvesting a narrow decision from the inexperienced Kenji Yonekura and then he hung ‘em up. Becerra’s early career had been storied and difficult, as apprenticeships served in Mexico almost always were. He had dominated that landscape, even winning all three fights of a trilogy with a young version of another future monster, Jose Medel; the wear, perhaps, was beginning to tell upon him by the end.

All that said, he was capable of losing some strange fights, including a fourth round knockout to a journeyman called Dwight Hawkins in 1957 or to the inexperienced Cachorro Martinez in 1956.

Overall though, his career was one of excellence, punctuated by excellent wins.

#28 – Jose Medel (1955-1974)

Winning only six of his last twenty contests certainly but an ugly dent in Jose Medel’s paper record, but in truth he was always inconsistent.

Partly, this is down to his phenomenal longevity. When he turned professional, the heavyweight champion of the world was Rocky Marciano; by the time of his retirement, Muhammad Ali was enjoying his second stint as the king. Few careers span three decades without subsuming such scars.

It is for the greatest wins he achieved in that enormous career that he is lauded here, however:

Legendary puncher Jesus Pimentel, world’s #2 contender, with whom he exchanged knockdowns before taking the narrowest of decisions; ranked contender Ray Asis who he stopped in three; number four contender Manuel Barrios, outpointed over twelve; world number three contender Edmundo Esparza stopped in short order; deadly veteran Toluco Lopez, stopped in seven; number seven contender Eloy Sanchez out-pointed over twelve in defense of his Mexican bantamweight title; world number five contender Danny Kid outpointed in ten; Walter McGowan, the former flyweight champion, crushed in six.

Last, and by no means least, is his astonishing knockout victory over the incredible Fighting Harada. The two met in Japan in 1963 as Harada continued his assault on the bantamweight division and it was business as usual for the first two rounds, the Japanese dominating with pressure and violence. Medel, bred in the desperate training ground that was the Mexican bantamweight scene, had lived it all before. Slowly, steadily, he sapped Harada’s legs with a countering body attack, and despite having won not a round on the official scorecards, dropped his man three times in the sixth with a wide variety of punches to secure a TKO. It was his finest moment.

For Medel never held the title. He was turned away once by the primed Harada, over three years after their first contest, and once by Eder Jofre, in 1962. Two harder assignments to win a world title cannot be imagined and while the cliché “champion in any other era” is a well-worn one, with Medel it fits.

Despite that, we can rank him no higher than he is seen here. Medel lost a lot; he lost to Ray Asis, he lost to Manuel Barrios, he lost to Harada, he lost to Eloy Sanchez, he lost to Danny Kid – he lost to many of the contenders of whom his win resume is comprised. This makes for a complex situation from the perspective of rankings, compounded by his losses to numerous lesser fighters.

In fact, Medel could be argued lower – lower than Becerra for example, who defeated him three times. Thirty-one losses is a few too many for him to rank with the true elite.

#27 – Pedlar Palmer (1891-1919)

Pedlar Palmer has a problem, and the problem is Jimmy Barry.

The wonderful old “paperweight” champion made a claim for the newly founded bantamweight title in 1894 which is generally held by most sources, and for most of the 1890s. This is despite the fact that fights staged in defense of that title were almost non-existent. What this resulted in was the emergence of regional champions making a claim to the world title which were sometimes acknowledged by the press of that time but who are historically relegated to “belt holders” rather than genuine champions.

Palmer was such a man.

He was also a third generation fighter who cut his teeth on the cobbles, a man whose BoxRec record represents just a sliver of his actual combat experience. The Marquis of Queensbury rules suited him, however, as indicated by his nickname “Box o’ Tricks”, a man who “never fought the same way twice”, who developed strategy across the canvas even as he felt his hapless opponents out.

His fighting history traces the bantamweight limit from 112lbs through to 116lbs where he made his bones. By 1898 his claim to the title was being taken seriously and on the British side of the Atlantic was read as truth. Billy Plimmer was his chief dance partner in the UK and he was a worthy one; having out-boxed a creaking George Dixon over the short distance in 1893 he was first jabbed to a standstill by Palmer in 1895 before being brutally stopped in the rematch in 1898. When Palmer sailed for America in 1899 he was 5-0 in “world” title fights and supposedly unbeaten under Marques of Queensbury rules.

In America he ran into a human tornado, a butcher, a blood-soaked brute so in excess of even his ability to control that he was crushed in a single round: Terry McGovern, the archetype for every destroyer ever to have followed him, had landed.

Even after this, for all that he was no longer a man invincible, Palmer did good work, not least against the fine European champion Digger Stanley. But, like so many who tangled with McGovern, Palmer was never truly the same.

#26 – Orlando Canizales (1984-1999)

Orlando Canizales was one of the most brilliant and complete bantamweights in history. He had a gorgeous short lateral movement that he could engage right in front of an opponent, stepping left or right to open up new angles and giving him control over his planes of attack against the limited opposition he met in his 118lb career. An enhancement to this was his developed technical acumen that allowed him to develop one of the most complete body attacks of the late 80s and 90s; but he was also a sharpshooter who was capable of landing short punches with both fists to the head of all but the most elusive fighters. A withering left uppercut completed an arsenal as exhaustive as any at the poundage. Throw in elite stamina, workrate and an iron chin (Canizales was never stopped) and you have a lethal fighter who very nearly lived up to comparisons with Roberto Duran, made, not least, by Gil Clancy.

So why is he ranked here, barely inside the top thirty?

Canizales is the ultimate legacy victim of the alphabet era. In 1988 he took the IBF strap from Kelvin Seabrooks, a teak-tough but limited champion who ended his career with a record of 27-22. It was a crackling strap-winning performance, one of the last to be contested over fifteen rounds, Canizales scoring a stoppage in that final frame. He took just eleven in the rematch and in both fights he showcased a level of excellence that hinted at an all-time great career in the making.

Alas, Canizales elected to fight IBF mandatory contenders, as sorry a collection of fighters as has ever been assembled for a significant title reign. That reign was significant; he went 17-0 in defense of his strap.

But at no time did he match the world’s best. During Orlando’s time at the top, the most significant bantamweights in the world were Raul Perez, Israel Contreras, Jorge Julio, Yasuei Yakushiji and Junior Jones. Canizales didn’t bother to match any of them; in fact, he never matched anybody ranked in The Ring top five bantamweights for the entirety of his reign and almost certainly never met a fighter better than Seabrooks. Second among his opponents was likely Billy Hardy, ranked #10, who gave him a torrid time with an accurate jab in England in 1990. Canizales took a narrow decision in a fight that could have gone either way, before knocking out the Englishman in a rematch staged in the US.

His third most challenging opponent is hard to identify. It may have been prospect Sergio Reyes, who he out-pointed in 1994 but against an opponent with a record of just 10-0 it was probable that a knockout was the minimum expectation. Maybe it was Clarence “Bones” Adams, at least that is a name some might recognize, but Adams was little more than a prospect then and his four most recent opponents had an astonishing fifty-nine losses between them. It may have been Ray Minus, the solid former Commonwealth champion who he stopped in eleven in 1991, but Contreras, a man he should have been fighting, had stopped Minus in nine the year before.

Canizales was a wonderful fighter who sabotaged his own legacy in his slavish devotion to the IBF. Too brilliant to suffer a lower ranking, he ranks here above fighters who achieved more due to his apparent excellence in the ring. I leave the reader to determine whether or not this is just.

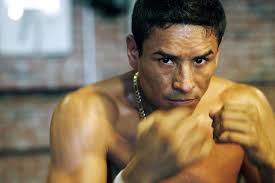

#25 – Rafael Marquez (1995-2013)

Like Canizales, Rafael Marquez (pictured) was the best bantamweight in the world for four calendar years, 2003 through 2006. Like Canizales, he was a victim of the IBF matchmaking policy which denied him legacy defining fights against Veeraphol Sahaprom and Hozumi Hasegawa. Like Canizales these fights likely would have elevated him to the top fifteen on this list had they been made – unlike Canizales he did do some excellent work against some of the better bantamweights in the division.

Former two-time world champion Mark Johnson finished Marquez’s education in 2001 when the two fought one of the more bizarre fights I have ever seen. A dull, tactical affair was brewing through three rounds, with Johnson out-prodding a reticent Marquez for a points lead that stretched into the second half of the fight. By that time a crude war had broken out, defined by fouling, missing, and hard power punches. Johnson lost by virtue of two point deductions he suffered in the closing spell of the fight – but was first announced the winner due to a mix up with the scorecards, then announced a winner again by different scores before Marquez was named the winner at the third time of asking. In the inevitable rematch, Marquez stopped Johnson in eight rounds, embracing for the first time what he was: a box-puncher who would generally only win tough fights when he was ultra-aggressive. It’s a thrilling concept.

It was a concept that nearly eluded him when he got the shot at Tim Austin and the IBF strap; once more, Marquez was out-prodded early, but he had learned to neutralize a much faster fighter with timing and aggression against Johnson, and sure enough he came surging through to victory with booming right hands, once again in the eighth round.

Austin, like Canizales, had failed to fight the best while wearing the IBF strap and Marquez continued the sad tradition. He did venture into the top five, at least, for two defenses against the same man, Silence Mabuza, the South African puncher, who he twice stopped, but his next best defenses were Ricardo Vargas and Pete Frissina. His title reign was approximately equal to Canizales’ for quality if not quantity – those pre-title victories over Mark Johnson (also among the five best bantamweights in the world at that time) just edge him ahead here.

Both men exited the division without losing their trinkets; whether or not it was worth their failures to match the best of their generation, only they can say.

#24 – Alfonso Zamora (1973-1980)

Five successful defenses of the lineal title and some of the most battlement-crumbling power in the bantamweight division’s history sneaks Alfonso Zamora in ahead of his compatriot Becerra and of alphabet boys Canizales and Marquez.

Zamora took the title from Soo-Hwan Hong, a man who had never before been stopped. Zamora stopped him in the fourth and remained the only bantamweight to ever stop him. Notably the smaller man in the ring, Zamora turned this trick not so much with one big punch as with a dozen tenderizing shots, a real wheelhouse attack born of a curious habit of coming square, making him vulnerable defensively, but as likely to land something menacing with the left as with the right. Hong did considerably better the following year, 1976, but succumbed again in the twelfth

In between, Zamora sealed his legacy with victories over Thanomchit Sukhothai, another big puncher at bantamweight, and the immortal Eusebio Pedroza. Pedroza towered over Zamora in a manner almost comical, but he was too far removed from his sensational featherweight prime to trouble the monster hitter from Mexico; Zamora knocked him senseless early for what was one of his easier title-defenses.

Zamora picked a gunfight with an even more terrifying bantamweight in 1977, lain low by the devastating Carlos Zarate before another knockout loss followed against underdog Jorge Lujan, and this, really, would have finished most undersized fighters as top contenders.

Not “El Toro”. Unquestionably unmanned by his horrific loss to Zarate, he rallied in 1978 to land one more blistering left-hook at the highest level, becoming the first man to knock out Alberto Sandoval, then ranked among the five best bantamweights in the world.

He packed a lot of action into a short career and even more power into that slender frame.

#23 – Lupe Pintor (1974-1995)

How you feel about Lupe Pintor’s placement here in the mid-twenties will probably depend most upon how you see his 1979 confrontation with the bantamweight giant Carlos Zarate. If you are one of the tiny minority that saw it for Pintor, then he should certainly be higher; if you are alongside the majority which includes reporters from Boxing Illustrated and International Boxing, all of whom scored it for Zarate, his ranking is more easily explained.

I had it to Zarate more narrowly, by a single point, a winner by virtue of the single knockdown of the contest perpetrated against Pintor in the fourth. That the wrong man won that night seems likely to me, but not beyond argument, and the near unanimity of the pressmen scoring ringside is valuable in directing our treatment of that result: Pintor was the beneficiary of a bad decision.

At the least, however, Pintor proved he belonged in the ring with Zarate that night and in my opinion fought him on even terms for great stretches. The resultant alphabet title reign was a respectable one, and was comprised of eight title defenses which included victories over Alberto Davila, Alberto Sandoval and the wonderfully named Japanese “Hurricane” Teru.

Always in shape, always dangerous, armed with a great chin and a very fine jab, Pintor dropped the title without defeat, departing for super-bantamweight where he added another alphabet strap.

#22 – Vic Toweel (1949-1954)

Vic Toweel boxed a truncated career that included one of the greatest wins in the history of bantamweight, his 1950 victory over world champion Manuel Ortiz. Ortiz is the greatest champion in the history of the division, and boxed one of the greatest championship reigns of any weight. Toweel was the man who ended it.

Already the reigning Commonwealth champion, Toweel, who was from South Africa, had already forged for himself a reputation as a ceaseless worker, a fighter of only middling power who threw ceaseless barrages of punches and yet never tired. They called him “the white Henry Armstrong”.

He needed all that and more to overcome Ortiz, as skilled a bantamweight as has ever lived. Probably Toweel’s timing was good in that Ortiz was ready to be taken but the many men had tried and failed to get the nail in the coffin; Toweel eased into the contest, all while getting hit by the Ortiz right hand, and parked his head on the older man’s shoulder. From there he outworked, out-hustled and out-fought one of the true greats of the prize-ring.

Toweel only staged three successful defenses of the crown before being out-hustled in turn by Jimmy Carruthers, but he showed no fear of the division’s best. The legendary ringman out of Morocco, Luis Romero, was bested in 1951 over fifteen rounds bookended by lashing punches that dropped the more experienced man in the first and last rounds; Peter Keenan, the wonderful Scottish bantamweight, then undefeated, was shorn of his “0” over the distance the following year.

In Ortiz, Keenan and Romero, Toweel arguably defeated the three best bantamweights in the world barring Carruthers. When he began to slip, struggling with the weight and therefore the terrible workrate he demanded of himself, he was suddenly vulnerable, but in his short-lived prime he was untouchable, and against an arraignment of opposition fit to test any fighter.

#21 – Frankie Burns (1908-1921)

Frankie Burns lost a lot of newspaper decisions coming up, appearing in and around New York’s small halls; you can almost see him trying to decide whether or not boxing was for him as the months passed by and he was drawn inexorably into her bloody arms.

His luck was never really in. He was turned away once apiece by the Attell brothers in 1911 but a series of wins against lesser lights bought him a title shot against Johnny Coulon in 1912. Fighting the champion on even terms up until the twentieth and final round, he slipped and upon rising shipped four hard punches to the champion – these bought Coulon a desperately narrow decision. The two fought a rematch in 1913, Burns “the more eager and for the better part of the bout the aggressor” by the wire report, but once again squeezed out of victory, this time by way of a draw.

Burns continued to campaign, to grind out results, to prove himself worthy, and in 1915 chance came knocking again, this time in the form of another lethal champion, Kid Williams. “For the first half of the bout,” wrote The Washington Times, “Burns looked to be a certain winner.” In the eighth, he even had the Kid in something approaching serious trouble. Williams rallied and hurtled down the homestretch, rescuing his title with a draw.

Burns campaigned desperately for a rematch but would never receive one. In fact, it took the summiting of a new and legitimately fearless champion to give Burns another swing at title honors, Pete Herman, one of the greatest bantamweight kings of all. “Too young, too speedy, too strong” was the take of the wire report on Herman’s twenty round victory over Burns in what was Burns’ fourth and final title shot. A tale of gritty and determined failure then; but here’s the rub.

Burns beat Herman.

Twice.

The first time was 1914 as he campaigned for another shot in the wake of his ten round draw with Coulon. Burns handed Herman the first and only stoppage loss of his incredible career via a body-attack that was so vicious Herman’s corner threw in the towel. “His manager’s actions,” went the wire report, “saved him from a knockout.”

The second time was in 1918, after Herman had defeated Burns for title honors in an over-the-weight match with the championship firmly protected from any exchange of hands. Burns took the better of an eight round decision and some small modicum of comfort.

In addition he defeated Memphis Pal Moore on no fewer than three occasions, and on two occasions bested another immortal bantamweight champion, Joe Lynch.

As nearly men go at bantamweight, Burns is the best.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles1 day ago

Featured Articles1 day agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden