Featured Articles

Open Scoring in Boxing: Yes or No? Part Two of a TSS Survey

(PART TWO: M-W): We asked 48 noted boxing buffs how they felt about open scoring. Specifically we asked, “Are you in favor of open scoring whereby the scores of the judges would be revealed after each round or at one or more intervals during the fight? If so, why? If not, why not?”

The respondents are listed alphabetically. Part One (A-L) ran yesterday (Tuesday, Oct. 2). Here’s the concluding segment. A hearty thanks to all that took the time to share their thoughts.

ADEYINKA MAKINDE—U.K. barrister, writer and contributor to the forthcoming Cambridge Companion to Boxing. Open scoring would detract from the drama of what the final decision will be should the fight endure to the allocated distance. So entertainment wise, it is not of particular value. Neither is its value enhanced in so far as the notion that it might improve the quality of judging. After all, the idea surely is not to put pressure on a judge whose scoring appears off base to a section of the crowd, or to substitute judges mid-fight for “getting things wrong.” This is a non-issue. Instead the focus should be on determining the professional competence of judges as well as their integrity.

JOHN McKALE–prominent boxing judge: No, 100% not in favor. The mind through the eyes of each judge should not be compromised by anything, including what the other judges may be determining.

PAUL MAGNO–author, writer and boxing official in Mexico: I don’t like open scoring. It does absolutely nothing to help the integrity of judging, but it ruins some key elements of intrigue and suspense when it comes to the fight and the announcing of a winner. If boxing is serious about judging reform, then they need to do the only thing that matters– overhaul the entire incestuous system and create more of a separation between the promoters and the selection of officials.

SCOOP MALINOWSKI—boxing writer, author, “Mr. Biofile”: Open scoring is just another system that can be corrupted and surely will be corrupted. I’d rather see former pro boxers and champions in the role as judges, but they can be corrupted too.

LARRY MERCHANT—HBO boxing commentator emeritus; 2009 IBHOF inductee: I’m opposed to open scoring because I witnessed a couple of such experiments that fell flat. Either the winning fighter, knowing the score, coasted through the late rounds and/or the losing fighter failed to respond, accepting defeat. The drama of uncertainty works best in prize fighting.

ROBERT MLADINICH — former NYPD police detective, author and boxing writer: I am not in favor of open scoring because awaiting a close decision is much of the fun of a good, close fight. Unfortunately the judges often get it wrong, which ruins the entire experience. That does not justify the open scoring. There should just be better judges.

HARRY OTTY—author, historian, part-time boxing coach: Absolutely in favor of ‘open scoring.’ How many close fights may have had a different result if the corner that felt they were ahead knew, without doubt, that they were actually behind with a couple of rounds left in the fight? I have coached amateur boxers for over 30 years and the closed scoring sucks – corruption is also rife. The best period we had was when the computer scoring (a button-push for each punch landed – not an ideal set up) was revealed at the end of each round. If you lost the first of three you at least had the option to alter tactics. Boxers/coaches who can adapt to what is happening as a result of the known score would also be proving their skill/superiority in the ring. TACTICS! From an open and transparent perspective it may have the side effect of making all judges (promoters/governing bodies) more accountable.

MARY ANN LURIE OWEN–boxing photojournalist extraordinaire: In 12-round title fights, scores should be announced after the 4th and 8th rounds.

JOE PASQUALE – prominent judge and recent NJ Boxing Hall of Fame inductee: As a fan, my thoughts are that this is the one sport that holds the suspense of the outcome until the third judge’s score is read by the ring announcer. Also, I have worked a few of these score progressions announced throughout the fight. The fighter with the big lead going into the later rounds just stopped engaging and coasted the last few rounds, taking the edge off a good fight with the possibility of a stoppage going into that tough 12th round.

DAVID PAYNE—U.K. boxing writer: I’m not in favor. Open scoring impacts intent of fighters and crowd reaction impacts officials.

J. RUSSELL PELTZ—venerable Philadelphia boxing promoter and 2004 IBHOF inductee: Terrible idea. A boxer with a big lead avoids contact down the stretch. Takes away suspense. Better solution is to get better judges.

ADAM POLLACK–author, publisher, and boxing official: There are pros and cons. The pro is it would allow the fighter who was behind to make adjustments and potentially fight harder, because it would make him realize that what he was doing was not as effective in the judges’ minds as he thought it was. On the other hand, it can allow one fighter to coast if he realizes he is well ahead, which can cause fights to become boring, and it eliminates the drama. When neither knows whether or not they are ahead, they fight harder, fearing the unknown. But what boxing really should do is stop using incompetent judges, and bring back the 15-round championship fight. Open scoring simply shows the fighters and the world how terrible the judging is as it is happening. It doesn’t change the fact of bad judging.

BRIAN POWERS–former fighter: Show them so the fighter knows and can turn it up if he’s behind.

JACQUIE RICHARDSON–Executive Director, Retired Boxers Foundation: I fail to see what difference that would make. Good judges will be good judges and bad judges will remain bad judges. The only positive outcome would be if the corners know, and the boxers come out and make adjustments to more convincingly win rounds. Another positive thing would be to see if the judges know what ring generalship is and the real difference between power shots and pity-pats.

CLIFF ROLD—boxing writer; founding member of the Transnational Boxing Rankings Board: I’m not in favor of open scoring of any kind/time. I think it changes the approach of fighters and those with leads have an impetus to disengage. That’s bad for the entertainment factor. The second Bell-Mormeck fight at cruiserweight soured me on it. It went from eight rounds of all-out war to a chase scene.

FREDERICK ROMANO–former ESPN researcher and author: My general feeling is I don’t believe it is necessary. It cuts both ways. Knowing a fight is dead even going into the last round could lead to some supreme efforts. It also might result in over-caution. However, I would like to hear from the fighters themselves as to whether they are in favor of it. Would they find it beneficial from a strategic standpoint? If they do, maybe we need to depart from tradition. I think what might be more important is that we improve the quality of judging. With quality judging the need for open scoring is mitigated. Also, using five judges for championship bouts might be helpful to reduce the potential impact of corruption and would overcome even two poor scorecards, saving some bouts from the wrong result.

DANA ROSENBLATT–former world middleweight champion; inspirational speaker: I am not in favor of open scoring. Although potential corruption is shrouded in part by allowing scoring to be done in a way that no one knows until the fight is over, I am not in favor of it. Instead, how about mandating that judges for all boxing matches are selected exclusively by the state boxing commissions of the states where the matches take place and not the promoters? I think this would make a difference.

LEE SAMUELS–veteran Top Rank publicist: We wouldn’t change it. There is always suspense how a fight is being scored. And in today’s world of Twitter, the top ringside writers tweet how they are scoring – that is good enough for me and for the fans who are watching.

TED SARES–TSS writer: In general, I dislike the concept but I’d be willing to see how allowing the scores to be read at the end of three rounds in ten-round fights and at the end of four in 12-round fights would work out—on a six-month trial basis.

ICEMAN JOHN SCULLY—former boxer, trainer, commentator, he’s done it all: There is no way open scoring should be allowed. It would kill all the potential for great drama in the sport of boxing. If it were implemented, it would backfire catastrophically.

MICHAEL SILVER–author, historian: I think it warrants an experiment for several months and in all fights to see how open scoring affects the fighters, corner men and fans in the arena. Mixed feelings about it but worth a try and then evaluate.

ALLAN SWYER–documentary filmmaker, writer, and producer of the acclaimed El Boxeo:Remember Oscar dancing away rounds because he knew he was far ahead in points? We’ll see far more of that kind of behavior with open scoring. My answer is a resounding NO!

DONALD L. TRELLA–prominent boxing judge: I am not a proponent of open scoring. I think part of the excitement that is generated by boxing is the announcement of the winner at the end of the fight. Everyone is on edge and anxious to hear the scores. There are also many ways a fighter can use open scoring to their advantage and diminish the action. For example, if a fighter is way ahead after seven rounds and has a shutout going, what’s the benefit of mixing it up the rest of the way? The fighter in the lead could just dance and stay out of the fray for the remaining five rounds leading to a very boring bout. Another example might be where a fighter is injured by an accidental foul. After four rounds are completed and he knows he’s ahead, he may say he can’t continue due to the injury and win the fight knowing what the score is after 4 rounds. What if a judge realizes he is wide compared to the other judges, does he start to score rounds differently to bring his or her scoring more in line with the other two judges? Very little upside… lots of down side. I actually could go on and on with a lot of examples.

GARY “DIGITAL” WILLIAMS— the voice of “Boxing on the Beltway”: I am totally against open scoring. This takes the excitement of wondering what the final judge’s score will be. Back in April of 1999, there was the Triple Jeopardy card in DC where they tried three types of open scoring — announcing the score after four rounds, after six rounds and after every round. Mark Johnson’s bout was the one tried after every round. After the bout, Mark told me that he knew after about eight rounds that he was well ahead on points so he just coasted to the win. Fans did not get a chance to see his true greatness. Open scoring just does not work on any level.

BEAU WILLIFORD–former trainer and the glue of boxing in Cajun Country: I favor open scoring either way. I think open scoring would provide better boxing matches!

PETER WOOD–former fighter, writer,author: I’m all for the transparency of open scoring, but it wouldn’t work the way we would like. A boxing match’s emotionally-charged environment can be dangerous—and VERY dangerous to a judge who doesn’t score a round like the crowd wants it to be scored. The masses are asses and judges would be too easily influenced and swayed for their own safety

OBSERVATIONS:

Those opposed to Open Scoring overwhelmed those for it by a margin of 40-9. Jim Lampley said he was against it because it kills suspense for fans, places fighters at risk if they fall behind and then take risks not warranted by their abilities, while conversely encouraging a leading fighter to take fewer risks — and risk is at the heart of the sport. Larry Merchant added that he had witnessed a couple of such experiments that fell flat. Either the winning fighter, knowing the score, coasted through the late rounds and/or the losing fighter failed to respond, accepting defeat. The drama of uncertainty works best in prize fighting. J. Russell Peltz, in common with several other respondents, said a better solution is to get better judges. Another frequently-heard comment was pinpointed colorfully by Peter Wood: “A boxing match’s emotionally-charged environment can be dangerous—and VERY dangerous to a judge who doesn’t score a round like the crowd wants it to be scored.” And Steve Farhood summed things up nicely by stating, “..it places undue pressure on the judges and eliminates one of the most dramatic moments in boxing–when the ring announcer reads the final scores in a close fight.”

Some of those in favor, such as Bill Caplan and Mary Ann Owen, favored the WBC plan of open scoring during intervals, rather than after every round. And others thought there would be value in trying it for a trial period.

Ted Sares is one of the oldest active power lifters and is the oldest Strongman competitor in the United States. He recently won the Maine State Championship in his class. He is a member of Ring 4 and its Boxing Hall of Fame.

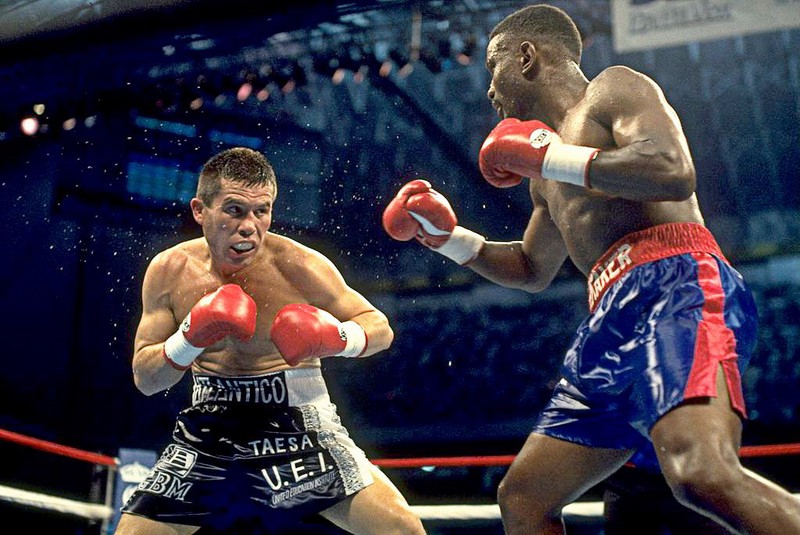

Photo: Julio Cesar Chavez and Pernell Whitaker battle to a controversial draw in San Antonio.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux