Featured Articles

In Boxing, Offense Sells Tickets But Defense Wins Fights

At its core, its essence, the sport of boxing is relatively simple. In a nutshell it comes down to hitting your opponent and not getting hit. And yet, when watching a boxing match live or on television, many times you’ll witness two guys pummeling each other, seemingly without any regard for defense.

If a poll was taken and fans were asked if they prefer action-packed bouts or defensive matches, the vast majority would probably choose the former. Cuts, bruises, welts and bloody noses are part of the sport’s appeal for many. It seems the more blood and gore, the better.

The thinking goes defensive battles are for the most part boring. Case in point would be the May 2015 welterweight mega-fight between Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao, which was late in coming, but still a massive money-maker.

The bout went the distance and had little action. Mayweather easily captured a unanimous decision, but over the course of 12 rounds, threw and landed very few punches. When Mayweather wasn’t standing right in front of Pacquiao, he was on his bicycle, dancing around in the ring.

Pacquiao connected and threw even fewer punches and looked confused and out of sorts, later claiming a shoulder injury.

The fight didn’t live up to its billing, primarily because neither boxer forced the action. This is what makes Mayweather so extraordinary. Try as one might, it’s never a picnic being in the squared circle with a defensive genius and, make no mistake, Mayweather is at the top of the food chain when it comes to defense.

When Mayweather collided with a past-his-prime Shane Mosley in May 2010, early in the second round Mosley tagged Mayweather with two solid rights, which buckled his knees and had the fans in the MGM Grand Garden Arena on their feet. Never panicking and never flinching, Mayweather simply held on, not allowing Mosley to extend his arms and follow up, eventually earning a one-sided unanimous decision triumph.

Now think of the best and most exciting fights. They’re freewheeling affairs with lots of action, like what Diego Corrales and Jose Luis Castillo offered in May 2005 at the Mandalay Bay with the World Boxing Organization and World Boxing Council lightweight titles on the table.

The bout was filled with ebbs and flows with Corrales, whose left eye was practically closed, getting knocked down twice in the beginning of the 10th round, then rallying and having Tony Weeks, the referee, halt the action later in round 10 in what was voted Fight of the Year.

While offense wins the hearts and minds of the fans and media, often times the defensive component is overlooked and underappreciated.

Just think of other sports. Who likes a 2-1 baseball score? Or a 14-10 football score? Or a 45-39 college basketball score before it had the shot clock?

The critics would say there’s not enough scoring. Not enough action. Too boring. But the purist would counter that a 2-1 baseball contest is a thing of beauty. It’s a pitchers’ duel. Great artistry. You know, Greg Maddux versus Randy Johnson.

Ditto for football. It was simply two great defenses playing at its peak. Think of the 1985 Chicago Bears.

No one will deny the greatness of featherweight king Willie Pep or three-time heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali.

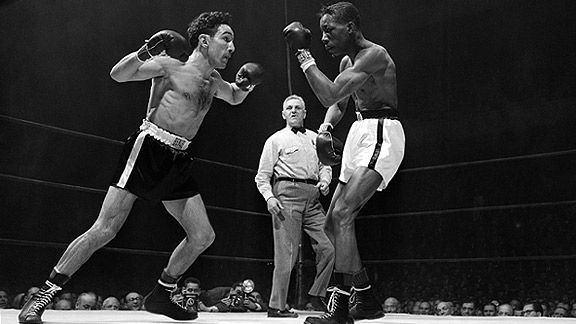

Pep (pictured against four-time opponent Sandy Saddler) and Ali were peerless in part because of their ability to step aside when the heavy artillery was within close range.

Pep, who was voted by the Associated Press as the No. 1 featherweight of all-time and was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990, was a defensive wizard. He held the featherweight title from 1942 to 1950 and finished his career with a 229-11-1 mark and 65 knockouts.

Ali was at his very best when moving, dancing and on his toes, making full use of the ring while enticing his foe to chase him. He was a master at bobbing and weaving, sticking and jabbing. His jab stung and he also possessed a solid right hand that could floor any man. He was at his pinnacle beginning in 1964 when he upset Sonny Liston in Miami Beach for the title until 1967 when he fought Zora Folley at Madison Square Garden.

The Folley fight was Ali’s last before being stripped of his crown and forced into inactivity for three-and-a-half years because of his then unpopular stance of refusing induction into the United States Army on religious grounds.

When he returned to the ring, he was good and sometimes even great, but there was ring rust and aging present.

Perhaps Ali’s greatest moment came in Kinshasa, Zaire, in October 1974, when he faced the undefeated and fearsome George Foreman with the WBA and WBC belts on the line. Foreman had an explosive knockout punch with either hand and many saw this as a massacre on the highest order.

Ali, at 32 and perhaps with fading ring skills, used his now legendary rope-a-dope defensive strategy in order to save his strength and it worked like a charm as the 25-year-old Foreman expended so much energy that he wore himself out and was floored in the eighth round.

Mayweather is regarded by many as the finest defensive fighter of his generation. Before Mayweather, it was welterweight king Pernell Whitaker, who capped his 16-year career with a 40-4-1-1 mark and 17 knockouts. Whitaker, who won titles in four weight classes, was a once-in-a -generation talent based solely on his ability to avoid punches. He was voted fighter of the year by The Ring magazine in 1989.

When Mayweather was asked about his over-the-top ring skills, he famously said. “My job is to win the fight. I don’t want to get hit. I’m trying not to get hit.”

At a press conference I attended at the MGM with Ray Leonard, Thomas Hearns and Bernard Hopkins present, a reporter asked Mayweather who he thought was the greatest boxer of all-time. “I think that I am,” said Mayweather, who ended his career with a 50-0 mark and 27 knockouts. “I know that there have been great fighters in the past like Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Louis and many others. But they all lost. I haven’t. That’s why I think I’m the best.”

Pepe Reilly, who boxed as an amateur and was a member of the 1992 United States Olympic boxing team that included Oscar De La Hoya, is currently a trainer.

Reilly, who toils in the corner for former lightweight title holder Ray Beltran, said an offensive fighter can be taught the basic defensive principles, but it’s not always easy to grasp. “It depends on the fighter’s ability,” he said. “As a trainer, I make adjustments based on body structure in order to teach that particular boxer how to act out on defense.”

Reilly, who went 15-4 with 11 knockouts as a professional, said he would prefer to train a defensive fighter. “Personally, I’d rather have a defensive-based boxer that could figure things out offensively,” he said. “If a fighter goes straight forward only, his one-dimensional style has its limits. And there is no room for the ever important changes needed.”

“Principles of defensive fighting for me are based on distance,” said Reilly. “If a fighter gets too close he is susceptible to smothering and if he is too far away, he isn’t in range to interact. Based on body positioning, a fighter can understand what to do.”

Reilly says that defensive fighters are overlooked and underappreciated. “(They) should absolutely be given more credit than they get. A good defensive fighter can inspire others to understand the principles of the art, which is to hit and not get hit,” he says.

Another practitioner of the defensive style is two-time Olympic bantamweight king Guillermo Rigondeaux. The Cuban refugee, whose only setback as a pro was to Vasyl Lomachenko in December 2017, is known for his fast hands, counter-punching ability and being extremely elusive, all valuable traits inside the ring.

“Guillermo is probably the greatest talent I’ve ever seen” said Freddie Roach, a seven-time Trainer of the Year and Pacquiao’s longtime cornerman. And yet Rigondeaux isn’t as marketable as he could or should be, with much of this due to his boxing style which isn’t fan-friendly.

Again, it seems it’s all about offense, offense and more offense. That’s what gets people’s attention and what sells tickets and pay-per-view buys.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this article at The Fight Forum, CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles21 hours ago

Featured Articles21 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden