Featured Articles

Ralph `Tiger’ Jones, Conqueror of Sugar Ray Robinson, was the Ultimate Gatekeeper

Being a gatekeeper, especially in boxing, can be a lonely and underappreciated function. And in the 1950s, a golden age for the sport, that might have been especially true for a highly competent but not-quite-elite middleweight named Ralph “Tiger” Jones, who fought so often on the Gillette Cavalcade of Sports’ Friday Night Fights that he came to be known as “Mr. Television,” a sobriquet he shared with another frequent face of the relatively new medium, comedian Milton Berle.

Jones, who was 66 when he passed away on July 17, 1994, is not enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame. The Brooklyn-born, Yonkers, N.Y.-based scrapper has never even appeared on the IBHOF ballot. Then again, why should he have been? His career record of 52-32-5, with only 13 victories inside the distance, isn’t particularly impressive, unless you take a closer look at the who’s who list of guys with whom he shared the ring. He holds victories over, among others, IBHOF Hall of Famers Sugar Ray Robinson, Joey Giardello and Kid Gavilan (Giardello and Gavilan each defeated him twice), and he gave such capable and even world-class fighters as Gene Fullmer (twice), Laszlo Papp, Bobo Olson, Johnny Saxton (twice), Joey Giambra (twice), Rocky Castellani (twice), Paul Pender, Johnny Bratton, Rory Calhoun (twice), Joe DeNucci (thrice), Bobby Dykes, Chico Vejar, Charlie Humez (twice), Victor Salazar, Ernie Durando and Del Flanagan all they could handle.

Given the high level of competition he so routinely faced, it is remarkable that the Tiger was stopped only once, and even that was a bit of an outlier, a one-round TKO against someone named Henry Burroughs on Jan. 13, 1951. Burroughs, who went 3-4 in an abbreviated professional career, quickly vanished from the fight scene, but for Jones, who had come in 9-0, the shocking defeat might have had the effect of instantly downgrading him from hot prospect to “opponent” and, ultimately, gatekeeper of a loaded 160-pound weight class. Interestingly, Jones had virtually toyed with Burroughs in winning a four-round unanimous decision only two months earlier.

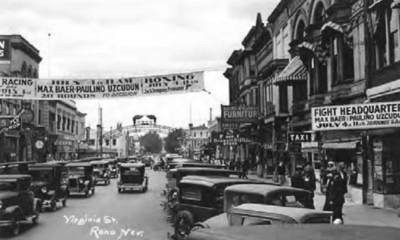

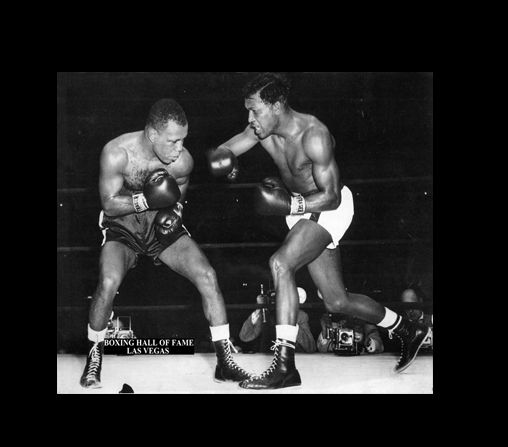

There are those who insist that Jones’ most shining moment inside the ropes came when he stopped Dykes (career record: 120-23-8, with 57 KOs) on March 8, 1954, in Brooklyn when, well behind on points, he rallied to register two emphatic, outcome-shifting knockdowns in the 10th and final round. But even that keepsake triumph pales in comparison to what took place in Chicago Stadium on Jan. 19, 1955, when he presumably was served up as a sacrificial offering to the incomparable Sugar Ray Robinson. Sugar Ray, then 33, was in the early stages of a comeback after he failed to make it big as a tap dancer on a tour of Europe. Fighting for the first time in 2½ years, Robinson had stopped journeyman Joe Rindone in six rounds on Jan. 5, 1955, in Detroit, and the bout against Jones, an 8-1 underdog, was widely viewed as merely another step forward in the former welterweight and middleweight champion’s graduated path back to the superstar status he once held and almost everyone believed he would soon reclaim.

But the outcome that was anticipated by the in-house turnout of 7,282 and a national TV audience underwent a quick rewrite when Jones, who had lost his previous five bouts, was the aggressor in the opening stanza of the scheduled 10-rounder, which ended with the great Sugar Ray — who had come in with an incredible 132-3-2 record — bleeding from a cut to his nose. It was more of the same in round two, Jones adding to Robinson’s seepage when the living legend went back to his corner with another cut, to his right eyelid.

It should have been apparent to everyone, even then, that this was not going to be Sugar Ray’s night, and it wasn’t. Referee Frank Sikora submitted a scorecard favoring Jones by a 99-94 margin, with judges Ed Hintz and Howard Walsh seeing it as an even bigger rout for Jones, at 100-88 and 98-89. Years later, the punch-counters for CompuBox reviewed tape of the fight and determined that Tiger had connected on 232 of 407 (57 percent) to just 176 of 514 (34 percent) for Robinson.

But as is often the case when a legendary fighter is made to look something less than superhuman, the big story was not that Ralph “Tiger” Jones had won, but that a humbled Sugar Ray Robinson was now on his last legs, his nimble feet and fast hands left behind somewhere on nightclub stages in a far-away continent.

New York Journal American columnist Jimmy Cannon for all intents and purposes authored Sugar Ray’s boxing obituary in his paper’s Jan. 20 editions, opining that “There is no language spoken on the face of the earth in which you can be kind when you tell a man he is old and should stop pretending he is young … Old fighters, who go beyond the limits of their age, resent it when you tell them they’re through … what he had is gone. The pride isn’t. The gameness isn’t. The insolent faith in himself is still there … but the pride and the gameness and that insolent faith get in his way … He was marvelous, but he isn’t anymore.”

And this, from The Associated Press report of the fight: “The former welterweight and middleweight titleholder … who started his comeback after 30 months as a song-and-dance entertainer by kayoing Joe Rindone two weeks ago, was handed the worst beating of his career by Jones … Time and again Tiger drove Robinson into the ropes and mauled him pitifully.”

But as was the case with the false rumor in 1897 that novelist/humorist Samuel Clemens – better known by his pen name, Mark Twain — had passed away, any suggestion that Sugar Ray Robinson was finished as a top-tier fighter proved to be premature. The Sugar man held the middleweight championship five times in all, three of his title reigns coming after Cannon advised him in print that he was washed up.

“I never figure to win them all,” the battered Robinson said after taking his licking from Jones. “You’ve got to figure you’ll get beat somewhere along the line. I don’t want to quit. This was a test. Like my manager said, it was just too tough for a second fight on a comeback.”

And Jones?

He continued to get regular TV gigs because he was more skilled than many, doggedly determined to put on a good show and no day at the beach for any of the six world champions he fought on 10 different occasions. But he never got a shot at a world title, a cruel twist of fate for someone who not only had paid his membership dues in the school of hard knocks, but continued to pay them right up to the end, a 10-round, unanimous-decision loss to IBHOF Hall of Famer and three-time Olympic gold medalist Laszlo Papp of Hungary on March 21, 1962. Tiger was floored in three separate rounds, but true to his unyielding code of honor, he gutted it out to the final bell. His pride would not allow him to do otherwise.

As a child growing up in New Orleans and the son of police captain Jack Fernandez (career record: 4-1-1, 1 KO), a former welterweight of scant pro accomplishment whom I idolized as if he had been a world champion, it seemed to me that, if Tiger Jones didn’t appear every week on the Gillette Cavalcade of Sports, he was in the featured bout at least every month or so. The best of the gatekeepers from that glorious era deserve at least some reflected glory for hanging in with their betters, and Jones holds a special place in my recollections along with, among others, Florentino Fernandez (I liked to pretend we were somehow related), Holly Mims and “Hammerin’” Henry Hank, the Detroit middleweight and light heavyweight who fought so often in New Orleans (18 times) that I chose to believe he was almost as local as Willie Pastrano, Ralph Dupas, Percy Pugh and Jerry Pellegrini. Hank, who was 62-30-4 with 40 KOs in a career that spanned from 1953 to ’72, was a virtual replica of the never-say-die Jones, never fighting for a widely recognized world title (he did drop a 15-round decision to Eddie Cotton for the Michigan version of the light heavyweight championship) and losing just once inside the distance, on a ninth-round stoppage by Bob Foster on Dec. 11, 1964, in Norfolk, Va.

Yeah, that would be the same Bob Foster who would go on to become one of the most accomplished 175-pound champions ever and was inducted into the IBHOF in 1990.

Bernard Fernandez is the retired boxing writer for the Philadelphia Daily News. He is a five-term former president of the Boxing Writers Association of America, an inductee into the Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Atlantic City Boxing Halls of Fame and the recipient of the Nat Fleischer Award for Excellence in Boxing Journalism and the Barney Nagler Award for Long and Meritorious Service to Boxing.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story on The Boxing Forum, CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap 329: Pacquiao is Back, Fabio in England and More

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOpetaia and Nakatani Crush Overmatched Foes, Capping Off a Wild Boxing Weekend

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFabio Wardley Comes from Behind to KO Justis Huni

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDelving into ‘Hoopla’ with Notes on Books by George Plimpton and Joyce Carol Oates