Featured Articles

Springs Toledo’s eBook Excerpt: “The Uncanny” (Chapter 3)

It ain’t business. It’s personal.

Roy McHugh was a sports editor and columnist-at-large for the Pittsburgh Press until he retired in 1983. He’s a hundred and three now; still living in the Smoky City with a treasure trove of memories. He told me he shook one of the dukes of the St. Paul Phantom himself in 1924, only five years after those dukes were flying at the head of Harry Greb.

McHugh spent his childhood in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. He was nine and in his pediatrician’s waiting room when he picked up a copy of the Boxing Blade “and got hooked.” His pediatrician was a friend of Mike Gibbons, who had a gym in St. Paul and was managing fighters at the time. When the once-great middleweight came to town, the good doctor introduced McHugh and his brother to him. A week later a set of boxing gloves arrived at the boys’ address. A note was attached:

Put on these gloves and do your stuff,

Prepare for the days when roads are rough;

You’ll get a little groggy, but just give bad luck an uppercut.

Greb-Gibbons II was scheduled for June 23, 1919. Ringside seats sold for $10, $7.50 and $5. Grandstand seats were $3 and $2 plus war tax. Requests for reserved seats were coming in from towns and cities across Ohio, Indiana, and West Virginia, particularly those Greb had invaded. A contingent hanging around the training camps of heavyweight champion Jess Willard and challenger Jack Dempsey arrived in from Toledo.

Seven thousand streamed into Forbes Field to see what a master boxer could do against an avowed anarchist the second time around. Gibbons had gotten the better of him back in 1917 and figured he’d do it again. Greb, favored to win and with bravado on display, knew Gibbons was the goods. George A. Barton, sports editor of the Minneapolis Tribune did too. “A toss of the head, a slight twist of the body, and an intended kayo punch will finish in a foolish wave to the fans in the gallery,” he said. Gibbons spent a novitiate sparring with luminaries like Joe Gans and knew all the tricks that leave a “frustrated battler steaming about in fury.”

That was exactly Greb’s plan—steaming about in fury.

Jim Jab liked Mike. “Fistic class puzzles many mortals,” he wrote in the first line of the next morning’s Pittsburgh Press. “They fail to understand its fine points, its timing, feinting, and foiling. Among the hundreds of Pittsburgh fans…scores belonged to this clan.” In his estimation, which was a lonely one, anarchy won no more than two of the ten rounds. The Daily Post and the AP gave Greb six to Gibbons’ three with one even. The Gazette Times had Greb up six to two with two even.

Greb, avenged, took home $5,514.50 and continued on with the big get-even. In July, he caught up with Joe Chip in Youngstown, Ohio. Chip was and remains the only fighter to ever lay him out for the count. “It was funny how it all happened,” said Greb about the 1913 match. “Everything was going along smoothly until Chip started a long swing… instead of ducking the swing, I ran flush into it.” For days afterward, Greb said there were “sweetly caroling birds” in his head.

But he was a novice then. This time, he won all but one round. He toyed with Chip and laughed when his friends tried to spur him on. Hissed by the crowd and warned by the referee for using his head in close and for hitting in the clinches, he dropped his defense to let Chip do what he could in the last round. It wasn’t much. Chip, under siege in the final seconds, was forced into a corner and turned his back.

Avenged again, Greb headed home and cooled his jets for a week. Mildred accompanied him to Conneaut Lake in the northern part of Pennsylvania. “Great guns!” blared a headline. “Greb Loafs for a While!” To Greb it was “a summer’s rest.” A friend wondered at that.

“Rest? Why you haven’t rested at all!”

“Any time I’m not fighting three times a week,” said Greb, “it’s a vacation for me.

*****

Columnists tended to present Greb as a clean-living young man who never bragged and always credited his opponents. That image was a half-truth at best. Greb was as much a tangle of contradictions as anyone else, more so even, though his personality traits—the virtues and the vices—stirred up something that is off by itself in boxing history.

Those who knew him said he needed to fight often, that he thrived on “his marathon plan of meeting them all, one after the other.” He typically asked for two things—“fair terms” and “the hardest guy” and as a result, negotiations were rarely much more than an offer on one side and a shrug and a signature on the other.

Throughout his thirteen-year career, he was lionized for his “gameness” more than anything else. Exceptional even during an era overrun with folk heroes and iron men, he glowers across a century at celebrity boxers who dilly-dally until a rival ages or breaks down and then swoop in like scavengers, picking at the remains and claiming it as something it is not.

But Greb was too willing.

He went so far as to issue a public challenge to Jess Willard and said he’d donate his purse to the Red Cross. When Fred Fulton fought at Madison Square Garden, Greb was moving with every punch and murmuring that he’d pay $5,000 to fight Fulton that night. He opened negotiations with Luis Firpo, and said he’d fight Harry Wills in an arena or a gym just to prove that the best African-American heavyweight in the world wasn’t much. All of them towered over him and outweighed him by at least fifty pounds, which suggests that Greb either had screws loose or was a misanthrope raging against all men, including himself.

He was moody, surprisingly vain, and quick to take offense. If he lost a fight, he was known to call it a frame-up and at times announced his suspicions as facts. If he failed to dominate an opponent, he’d insist on another match and sometimes another and another to make sure his supremacy was understood.

When a bulletin was posted outside the Pittsburgh Press announcing Jim Jab’s opinion that he’d lost a fight the night before, Greb happened by and saw it. He ripped it off the board and threw it on the street. Then he went looking for Jim Jab.

In March 1919, he read about Ed Tremblay’s contention that he made Greb quit in the King’s Tournament and added Greb’s name to his record with a “KO 2 rounds” beside it. Greb promised “the beating of his young life for his presumption.” Tremblay wouldn’t fight him.

After one of his bouts in New York City he went to an all-night joint in Greenwich Village. The morning paper came in and he flipped to the sports section. Westbrook Pegler was there with Red Mason, watching him. “Harry read the stories, moving his lips, then pushed the papers away and sat with his face in his hands.” Mason leaned over to Pegler. “His wife’s sick,” he said. “He’s all busted up about it.”

“Hey,” Greb looked up. “Them bums say I blew a coupla rounds to that guy tonight. What do them bums know?”

In October 1919, the old “White Hope” heavyweight Frank Moran said Greb got a boxing lesson in a recent match, and Greb headed for the telephone. “Now listen,” he told the Daily Post. “You put a piece in the paper telling Frank Moran that if he really wants to fight, he’s looked far enough. I’m his man. What I mean is that he’s mine. Size doesn’t impress me.” Greb posted a grand for a forfeit and his manager was ready to bet that Moran would not only lose big, he would “break ground” when Greb engaged him toe-to-toe. Moran went quiet.

At times he seemed to target siblings—the Chips, the Gibbons—as if on a blood campaign. In the summer of 1912, we can place him in Wheeling, West Virginia for what looks like a spur-of-the-moment professional debut against Young Stoney Ritz. What happened in that fight is a mystery, but he returned to Wheeling twelve years later to fight Stoney’s younger brother. In the second round, Greb hit Frankie Ritz with a triple right hand combination that landed Ritz on his back with his feet “tangled grotesquely” up in the ropes. Ritz had to be carried to his corner; Greb walked off “without having disturbed his slicked and glossy hair.”

He rarely went down, but if he did, you were in for it. Soldier Buck claimed he knocked Greb down with a right hand and didn’t think he’d get up. “But he did—at the count of four. He then proceeded to beat me to death,” he recalled. “For two days after the fight, friends had to lead me around. Both of my eyes were closed.” There are reports of crowds howling at the referee to stop the carnage when Greb was in one of his sadistic moods, when he sought to prolong punishment out of “pure meanness.”

He was just as mean during sparring sessions. While Greb was training for a bout in a New York gym, Mason invited Jack Sharkey to spar with him. Sharkey, who went on to become the world heavyweight champion in 1932, sent a light heavyweight over instead. Greb felt slighted, got mad, knocked the light heavyweight out, and started taunting Sharkey—“Come on over!”

Roy McHugh described his fighting style as “an uprising of nature.” Clouds of rosin dust were kicked up as he tore after any and all, blitzing them to the body and the head, mauling, head-butting, yanking them off balance, ramming them through the ropes, and grinning the whole time. One of his favorite moves was to curl his left glove around the back of a neck and whale away with his right. And he’d laugh off criticism.

In the summer of 1919, he faced a parade of fighters who had no affinity for him, nor he for them. He relentlessly mocked Big Bill Brennan. Battling Levinsky couldn’t bring himself to tip his hat to Greb after yet another decisive loss. Knockout Brown and he were “enemies of long standing.” There was “bad blood” between him and Mike Gibbons and “the feeling is real,” said the Press. “Harry and Mike detest each other.” Jeff Smith shared a ring with him seven times, which exponentially increased their mutual antipathy. “They hate each other,” said the Daily Post.

Kid Norfolk can speak for all of them. “That Greb was mean,” he said in 1938, and opening his shirt, pointed near his sternum. “See that lump, big as an egg? Greb gave me that with his head. Still sore.”

What was driving him? There is evidence of disturbance in the historical record, in the little deaths a fat, crooked-eyed, grammar-school dropout they called “Icky” could be expected to suffer daily; in the choice of a confirmation name that promised violence, in the “wild rage” his father recalled—wild rage that thousands would buy tickets to witness.

Greb became famous for forcing his adversaries—those who would hurt him—backward and on their heels to put himself, the former victim, in control. In other words, his fighting style reflected his psyche. So did his nom de guerre. The name “Harry” was adopted at the onset of his career and is assumed to be a loving tribute to a dead brother, but it’s more than that. Icky Greb was a frog who imagined himself into a king, and the king had a name. “Harry Greb” was his reconstructed self, the man he aspired to become—fearless, ferocious, and covered in glory.

Memories of his ferocity wouldn’t fade for decades. Red Smith couldn’t bring up Gene Tunney’s name without shuddering at what was done to him by the “bloodthirsty Harry Greb,” he said in 1968; by the “carnivorous Harry Greb,” he said in 1973.

And yet Greb was always genial toward those who meant no harm. His neighbors on Gross Street liked him for “his sunny disposition.” He’d greet civilians with a smile and a warm handshake, and often shared stories filled with Jazz-era slang and devoid of proper grammar. He doled out tickets and whatever else he had in his pockets to the Pittsburgh newsboys who followed him around like his own personal cheering section. When he learned that one of their counterparts in Omaha scaled the wall of an auditorium to watch him fight and fell to his death, Greb sent his parents a check.

He counted many priests among his friends. Father Cox never had to ask twice if he needed him to volunteer at the Lyceum. The late-night knock on the rectory door at Immaculate Conception never startled Father Bonaventure; he knew it was Greb, back from out of town and stopping by with a donation. On Sundays, Greb went to Mass and limited his training to a long walk. He prayed novenas. Before a fight, he would seek out a priest for a blessing on his efforts. “He made quiet little visits to Our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament, asking for aid,” said Father Cox, who believed those prayers were answered—“He fought with the courage of a David. He never knew fear and was never tired.”

If he lost his temper or wronged someone who didn’t deserve it, he would apologize immediately and mean it. He didn’t always beat up on opponents. At times he would take it easy on substitutes who couldn’t hang with him, and when faced with a situation that would give him an unfair advantage, he’d behave as if a nun from St. Joseph’s was watching.

His loyalty is a favorite theme of half-forgotten folk tales. One of them begins with a frantic phone call from Youngstown where a friend had stopped for a drink and was being treated roughly. “Stay right there,” Greb said, then sped seventy-four miles north and barged into the saloon. He was still tossing the brute around when the bartender appealed to his friend to make him lay off. “I can’t afford to replace this whole joint,” he said.

In November 1919, young Jack Henry showed up at Greb’s training camp in Beaver Falls and was stopped at the entrance. The boy’s accent was familiar to Greb. “Are you a Limey, kid?”

“Yes,” Jack replied. “And in England they say you’re the greatest fighter in the world.”

“Let the kid in.”

A few nights later, Greb was beating up on Zulu Kid at the Nonpareil A.C. and there’s Jack in his corner, in charge of the bucket and sponge.

****

By the time Greb took Mildred and his contradictions to Conneaut Lake in July 1919 he was at the very least the greatest boxer in his division. But the only thing atop his head was a straw boater hat. He wanted a crown, and Mildred couldn’t buy one at The Rosenbaum Company at Sixth, Liberty, and Penn. It wasn’t like today—if you were a name-fighter back then the Five Points Gang didn’t dangle a belt and a random opponent in front of you for a percentage. And if they did, that era’s sports writers would have spotted the sham and shamed it into extinction. Greb had to find a way to get an official shot at the middleweight champion, and that was Mike O’Dowd.

Greb had already defeated two of O’Dowd’s predecessors in unofficial bouts, and in 1918 came damn close to defeating O’Dowd himself in what the Minneapolis Journal called “one of the most sensational bouts ever fought in the twin cities.”

Mason had a master plan for 1919. “Now what I intend to do is have Greb fight every man anywhere near his weight,” he said, “and really show who is the best fighter in the middleweight class.” He would force O’Dowd to the table.

Things were finally beginning to simmer in July when O’Dowd told the Gazette Times he’d be “tickled to death to get a crack at Harry Greb in a bout in Pittsburgh.” Other cities were also vying to match them. The Tulsa World mentioned that O’Dowd’s manager agreed to give Greb a shot at the title and O’Dowd “gave his word.” A week after that, a promoter in Tulsa said he signed O’Dowd to defend his title against Greb. At the end of July, an athletic association in Toledo said O’Dowd and Greb were set to meet on Labor Day. The New York Daily News was among those carrying the story. The problem was no one told Mason, who by then was wringing his hands over O’Dowd’s refusal to meet Greb.

On August 5, a matchmaker with the Keystone Club in Pittsburgh was trying to make the fight and flew to New York to meet with the champion and talk him down from the $7500 guarantee he was insisting on. On the 18th there was still talk of Toledo until O’Dowd put the nix on it—“positively refusing” to meet Greb before late in the fall. On the 27th, Greb stepped off the train in New York to meet man-to-man with O’Dowd, who said that he would accept Greb’s challenge for September 29 in Pittsburgh if his take was $5,000 with a better than 25% of the gate. It fell through. A promoter in Cincinnati signed Greb to “meet the best opponent he could get on the night of the opening game of the World Series” (later remembered as the Black Sox Scandal of 1919) and tried for O’Dowd. He figured he could do better than the flat fee of $5,000 Pittsburgh offered, but he couldn’t, and it fell through.

And so it went. From July through September 1919, promoters in Tulsa, Toledo, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati all tried and failed to sign O’Dowd to face Greb.

The middleweight king had his defenders though, even in Pittsburgh. Sergeant O’Dowd, after all, was said to be knee-deep in grime in the forest of Argonne during the war while Greb was stationed on a training battleship with a dummy smokestack and wooden guns in Union Square.

“Mr. O’Dowd is quite a man—to be explicit—all man,” said the Evening Tribune. But Greb made him nervous.

Ed Smith, a Chicago fight critic who refereed Greb-Gibbons II may be the reason why. A story was making the rounds that said Smith spoke with the champion in Toledo just before Jess Willard fought Jack Dempsey, and “solemnly warned Mike that ‘if he cared anything for his title, stay away from this fellow Greb.’” In November, O’Dowd faced Mike Gibbons five months after Gibbons lost to Greb. In December, he planned on touring Europe.

Had O’Dowd risked his crown against Greb in 1919, it is very likely Greb would have taken it a year earlier than his wife’s deadline, and, given his easy defeat of then-champion Al McCoy, about two years later than he could have. As it happened, Greb’s middleweight reign would not begin until 1923—after O’Dowd’s successor Johnny Wilson continued the tradition of eluding him for three years plus.

****

Greb was the bête noire of the light heavyweights and his ambitions were unsurprisingly blocked there as well. Gene Tunney, among the greatest boxers the division ever produced, learned early on that there was something of an abyss behind Greb’s dark and deadpan eyes. “He is not a normal fighter,” he was told. “He will kill you.”

In March 1919, Mason was arguing that Greb was the rightful middleweight and light heavyweight champion of the world. He justified it by pointing out victories over Jack “The Giant Killer” Dillon and his successor Battling Levinsky. At the end of the month, Greb boosted the argument further by beating Billy Miske, another star in the division. The claim was only hype, but many considered the title lapsed as Levinsky rarely defended it.

In September 1919, Greb demanded a chance and nearly got it.

The Miami A.C. in Dayton, Ohio had signatures from Levinsky and Greb to fight to a decision on the 8th. Greb wired them and insisted that Levinsky make a hundred seventy-five pounds ringside to make sure the crown was up for grabs. The date was switched to the 12th, the 8th, and then back to the 12th before it was postponed until the 15th because Greb was reportedly in a Pittsburgh hospital with boils on the back of his neck. Levinsky, in Dayton on the 12th, headed back to New York. The bout was called off altogether when the promoters couldn’t get in touch with him. Did he go on the lam? He never went near Greb again.

Levinsky was, of course, ready to accept a lesser challenge for more money. In October 1920, he defended against “Gorgeous” Georges Carpentier at Jersey City for 20% of the gate minus state taxes. The gate was $350,000 which means Levinsky’s take was $65,000. Carpentier had his way with him, knocked him out in the fourth round, and did his part to look like something promoter Tex Rickard could market as a credible opponent for heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey. In July 1921, Dempsey did his part and knocked Carpentier out in the fourth round, also at Jersey City. It was boxing’s first million-dollar gate. Carpentier earned a $300,000 purse—over four million today.

Greb could only hang his head.

He’d been trying for a fight with Carpentier since he went overseas during the war. In June 1919 there was talk of a $15,000 purse to meet him in France and in December 1919 Mason was still campaigning for a match in London or Paris.

Greb turned up at Carpentier’s training camp in Manhasset, Long Island before the Dempsey fight. Columnist Robert Edgren asked Greb if he’d like to take him on. “Any time,” Greb said, “on a day’s notice.” Later that day the two were introduced and Carpentier, who stood near six feet tall, laughed when he saw Greb, who stood no more than five eight. He’d heard all about this berserker running riot in three weight classes and said he expected a much bigger man. Greb muttered that he was “big enough” and asked him for a match.

Carpentier was friendly, but he wasn’t eager. He’d heard too much.

About a week before Dempsey-Carpentier, Greb was rolling his eyes at the French champion’s depiction by the press as “a man of destiny” and the so-called secret punch he was supposedly working on at his conveniently closed camp.

He was rolling his eyes again in Billy Lahiff’s tavern in New York City when the sports writers’ talk turned to Carpentier’s chances. Greb broke in. He asked them if they would like to know how good Carpentier was and then invited them to go with him to crash his training camp the next day. “If they let me box him I’ll prove to you he doesn’t stand a ghost of a chance,” he told them. “He can’t beat me, much less Dempsey.” A huge delegation went with him. Carpentier’s manager had a conniption fit. “No! No! No!” he said.

When Greb made Tunney look like a murder scene and took the second-rate American light heavyweight title in May 1922 at Madison Square Garden, Rickard strolled toward the ring as Tunney, “a bloody ruin,” was assisted out of it. Rickard told press row that he would offer Carpentier $150,000 to fight Greb for the light heavyweight championship of the world in July. Carpentier’s answer? Mieux vaut prévenir que guérir.

In June 1922, the AP reported the Frenchman’s “unexplained annoyance when the Pittsburgh fighter’s name was mentioned.” It can be explained now. He saw Greb around every corner, under the bed, in the closet; he saw his shadow on the terrace sipping noisette.

In September 1922, promoter Jack Curley was said to be in Paris securing Carpentier’s signature to defend his crown against Greb. That was just days before Carpentier met Battling Siki. Fate knocked Greb out of the frame when Siki knocked Carpentier out of his shoes.

Greb could do nothing about fate, though he could do something about Siki. “I will meet Siki anywhere in the world,” he said. “Anytime, anywhere.” Three offers came in. Greb was revving up when Siki inexplicably agreed to defend against Mike McTigue in Dublin on St. Patrick’s Day of all days.

Siki was robbed, McTigue was handed the crown, and Greb was sidetracked again. McTigue, he knew, would keep that crown in a locked box. He had faced McTigue twice already, and McTigue was lucky if he’d won one round in twenty. The first time they met, McTigue’s manager was hollering “Hold him, Mike!” from the first through the tenth rounds. “I think McTigue hit Greb once,” said the matchmaker. “‘Hold him’ Mike McTigue is in a class by himself when it comes to holding.”

McTigue was tentatively scheduled for a no-decision bout against Greb in June 1923 as a tune-up before facing Carpentier in July. McTigue was set to collect $100,000 to let him try to reclaim the crown and everyone was smiling until Carpentier hurt his hand and the date was postponed. McTigue’s manager by then was Joe Jacobs, who surprised him by elevating the Greb no-decision match to a championship match. McTigue made a noble statement about how willing he was to give anyone a shot and then priced himself out of reach.

McTigue lost the crown to Paul Berlenbach in 1925. Greb, middleweight king since 1923, told the Pittsburgh Courier that he preferred to face the plodding Berlenbach and become a double champion but was obligated to accept a greater challenge in Tiger Flowers instead.

Two years before Jack Delaney won the light heavyweight crown from Berlenbach, Greb signed to face him and was training hard when Delaney came down with appendicitis and cancelled.

Three years before Jimmy Slattery won the light heavyweight crown from Delaney, Greb beat him in his hometown.

Between 1922 and 1924, Greb went 4-1-1 against Tommy Loughran, Slattery’s successor.

In 1925, five years before Slapsie Maxie Rosenbloom beat Slattery to become Loughran’s successor, Greb did as he pleased with him and then reportedly returned to the night club where his unfinished highball waited on a table.

Had Battling Levinsky risked his light heavyweight crown against Greb in 1919, Greb almost certainly would have taken it. As it was, he proved himself a master of the division—barreling out of Pittsburgh to face six of the ten light heavyweight champions who reigned from 1914 through 1934. As the smoke cleared, his record against them stood at 16-1-1. Those he didn’t face, he chased.

The smoke is still clearing. What comes into view is startling: the greatest light heavyweight who ever lived may have been a middleweight.

__________________________

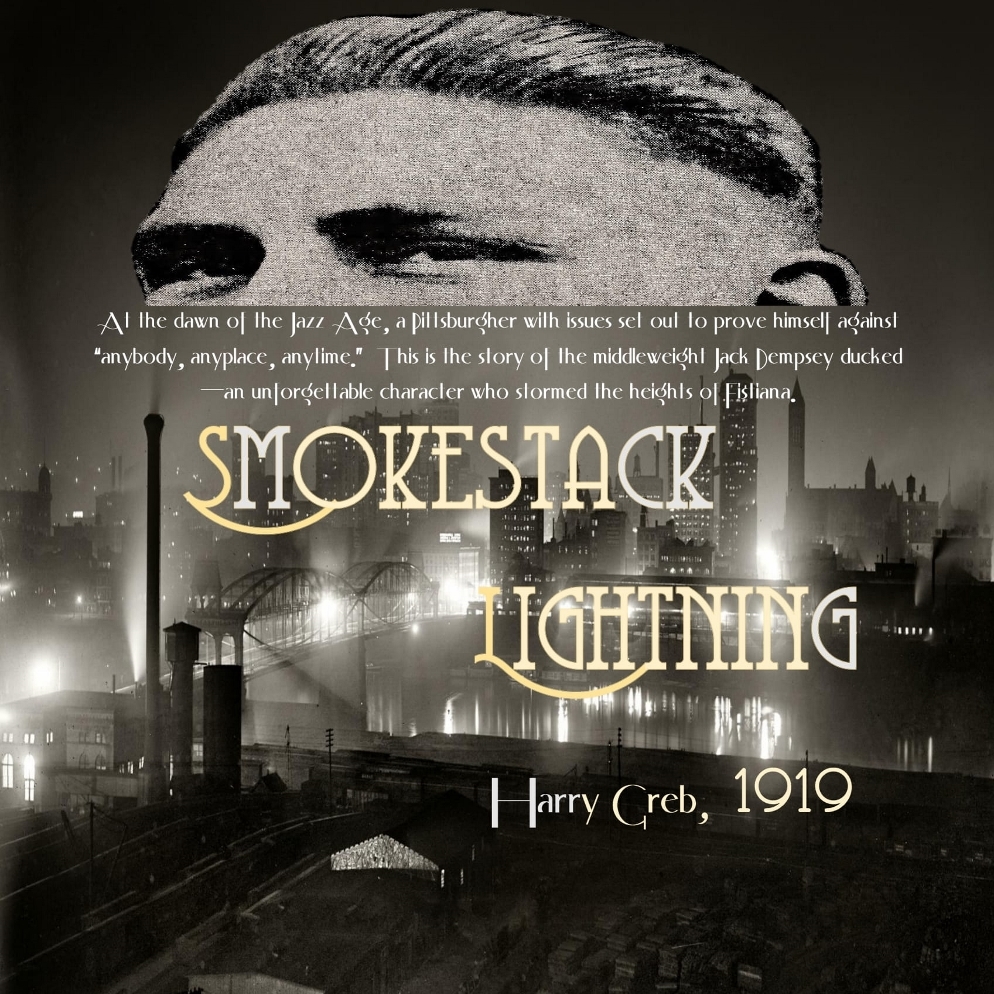

Smokestack Lightning: Harry Greb, 1919 is available now for only $7.99 at Amazon. Please CLICK HERE

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this article (Part 1) at The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

To comment on this article (Part 2) at The Fight Forum, CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles12 hours ago

Featured Articles12 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden