Featured Articles

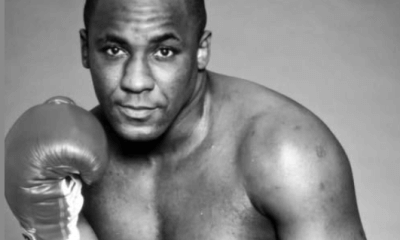

Golden Child Mike Lee Finally Gets the Chance to Prove His Doubters Wrong

Most professional boxers, for whatever reason, have nicknames. With as unadorned a given name as Mike Lee, you might think that the guy who on July 20 will challenge IBF super middleweight champion Caleb Plant, whose nickname is “Sweethands,” would also have a catchy nom de guerre. Ah, but what would it be? “The Fighting Would-Be Stockbroker”? “The Subway Kid”? “The Golden Domer”?

Lee (21-0, 11 KOs) is now 31 and he’s heard all the snide and very likely envious remarks since he turned professional on May 29, 2010, with a four-round unanimous decision over Emmit Woods at Chicago’s UIC Pavilion. From the outset of his pro career, Lee’s background stamped him as markedly different from most other fighters who are obliged to start at the bottom and, hopefully, work their way up to some degree of recognition and decent paydays. For Lee – affluent white kid, University of Notre Dame graduate with a degree in finance (he had a 3.8 grade-point average and offers from Wall Street) and backing from a powerful promotional company (Top Rank) – it must have seemed that he was starting at the top and would have to demonstrate he had enough of what it takes to avoid sliding toward the bottom.

And then there were all those television commercials he did for the Subway sandwich shop chain, the most prominent of which drew a massive audience when it ran on Super Bowl Sunday in 2013. Although he was just one of several athletes in different sports to appear in such spots during a marketing campaign that lasted several years – some of the others were football stars Michael Strahan, Ndamukong Suh and Justin Tuck, Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps, baseball slugger Ryan Howard, NBA standout Tony Parker and NASCAR driver Tony Stewart – Lee, who at that point had accomplished little of note, was clearly an outlier, famous mostly for being famous.

But Lee said those who resented him for taking advantage of the kind of exposure that almost never is afforded anyone who has not painstakingly established his bona fides would have done exactly what he did.

“I wasn’t going to turn down these amazing opportunities that I had outside the ring, and I don’t think anybody would, but obviously you get doubters and haters,” he once said of the criticism he has had to deal with solely because he does not fit the profile of what many think a fighter ought to be.

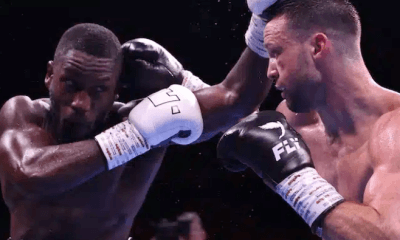

It has been years since Lee last appeared in a Subway commercial. The attention he once routinely drew for being different has been tamped down. But enough residual animosity remains to make him a target for some of the same thinly veiled or outright putdowns. At an introductory press conference in New York attended by both Lee and Plant, as well as Manny Pacquiao and Keith Thurman who fight on Fox PPV following the Lee-Plant match on Fox and Fox Deportes, Plant (18-0, 10 KOs) depicted himself as the dues-paying traditionalist who has had to scrap for everything he’s ever wrung out of boxing, while Lee’s education and prominence allows him any number of fallback life options should his first shot at a world title result in a crash-and-burn scenario.

After Lee, speaking first, said he has “nothing to lose” in a bout in which he is a significant underdog, Plant turned toward his smartly dressed opponent and said, “I’ve been doing this (boxing) for 18 years straight – no breaks, no distractions and no Plan B. I commend you for this, but there’s no college degree for me. No high school sports, no acting gigs, no Subway commercials. Just boxing, day in, day out, rain, sleet or snow.

“You may have a financial degree, but in boxing I have a Ph.D. And that’s something you don’t know anything about. If this guy thinks for one second that I would let him mess this up for me and send me back (to his hardscrabble beginning) … unlike him, I have everything to lose.”

Lee has heard it all before. As intimated by Plant and others, he arrived from Notre Dame’s Golden Dome with a silver spoonful of caviar stuck in his mouth. As such, he is merely dabbling in the fight game, which outsiders see as his hobby rather than his vocation, until it’s finally time for him to take advantage of his degree, put on thousand-dollar suits and head to work every morning carrying an expensive leather briefcase rather than a gym bag. And that could happen yet.

There is no shortage of evidence to suggest that Lee still is the beneficiary of circumstances that have always made him such a marketable commodity. For one thing, he has fought as a light heavyweight his entire pro career, yet is getting a world title shot in his first bout at a new and lower weight class. That in and of itself suggests some level of preferential treatment for someone who is not ranked in the top 15 at super middleweight by any of the four major world sanctioning organizations.

Without doubt, Lee’s path to the precipice of the world championship he has long believed to be his destiny has been comparatively obstacle-free. A multi-sport star at the exclusive Benet Academy in Wheaton, Ill., he first drew attention as a boxer after winning three straight Bengal Bouts titles at Notre Dame, his “dream school” to which he transferred after spending his freshman year at the University of Missouri. The Bengal Bouts were started in 1920 by legendary Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne on the principle that “strong bodies fight, that weak bodies may be nourished.” Toward that end, in Lee’s senior year the Bengal Bouts raised more than $100,000 to combat poverty in Bangladesh, where Lee traveled for two weeks to teach English and mathematics.

“Bangladesh opened my eyes,” Lee said of that experience. “To go to a Third World country like that and see people that are really struggling for simple necessities that we take for granted, it made me extremely grateful and, I think, a more charitable person.”

It came to the attention of Top Rank founder and chairman Bob Arum, who transformed blimpish Eric “Butterbean” Esch and Latina hottie Mia St. John into TR undercard staples, that there were a couple of amateur boxers at Notre Dame that might also someday prove useful to his company’s bottom line. One was Tommy Zbikowski, an All-America safety and punt returner for the Fighting Irish who had had his first sanctioned amateur bout at the age of nine but had retained his love of boxing even as his reputation as a big-play-maker in football increasingly steered him in that direction. Arum paid Zbikowski $25,000 to make his pro debut, as a smallish heavyweight, on June 10, 2006, in Madison Square Garden, where he stopped Robert Bell in one round.

Arum said his interest in Zbikowski was piqued not only because he was a star football player, but because of his college affiliation. “Oh, absolutely,” Arum said in acknowledging that “Tommy Z” probably wouldn’t have gotten the Garden gig had he played at, say, Weber State or Northern Iowa. “Notre Dame has a cachet to it in athletics and popular culture.”

Although Zbikowski wound up having eight pro bouts, seven as a cruiserweight, and won them all with five KOs, he remains better known for his football exploits at Notre Dame and with the NFL’s Baltimore Ravens, for whom he was voted special-teams player of the year in 2009.

And the other Notre Dame fighter to draw interest from Top Rank? It was the handsome, bright, personable kid who had helped build schools and health-care facilities in Bangladesh, a veritable Mother Teresa in padded gloves. If anything could transform Mike Lee into a prepackaged star, it was Bob Arum’s always whirling hype machine. And, for a while, it was a mutually beneficial arrangement, Lee compiling an 11-0 record for Top Rank until his contract ran out and he was unable to negotiate an extension to his liking.

Not that Lee ever was the phony creation as some have depicted him. Yes, he has a background of wealth and privilege, but it was not always so; his father, John Lee, served 18 years in the Army, most of those with the 101st Airborne Division, before he entered private life and made his fortune as the manufacturer of barcode machines. John reveled in his only son’s love of contact sports, and he did not object when Mike indicated that he’d rather try his hand, at least initially, as a pro boxer than as a wheeler-dealer on Wall Street.

“Both my parents grew up in the city (Chicago) under tough upbringings,” Lee noted. “My dad didn’t even graduate high school. And that’s how I was raised, not with a suburban vanilla outlook on life.”

Still, Lee’s career choice must seem confounding to some. But who’s to say someone, anyone, should not follow his heart?

“Boxing brought out an adrenaline rush that I was seeking,” Mike said of a passion that for him the business world could never duplicate. “I always excelled in different sports, but there’s nothing like boxing to me where it’s one-on-one. There’s no excuses, there’s no timetable.”

So fight fans have to view Mike Lee from two perspectives. One is that he’s the pampered suburbanite who was born on third base, in a manner of speaking, and will think he hit a home run if he advances another 90 feet to home plate. The other is that he’s as gritty and committed as anyone who gravitated to boxing from the ’hood or barrio. How many fighters of any stripe would or could have dealt with the nearly two years of debilitating pain that kept him sidelined until, four years ago, he received the correct diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis, which is similar to rheumatoid arthritis and causes inflammation, fatigue and headaches that made him feel as if his skull was about to explode.

“This is the culmination of years of hard work, sacrifice, pain, in and out of hospitals,” Lee said of the journey he has undertaken to get to this point. “Most importantly, getting somewhere no one thought I could get to. A lot of people didn’t think I could get to 10-0, 20-0, let alone (a shot at) a world title.

“I’m fine being the `B-side,’ the underdog. I feel like I got nothing to lose in this fight. I’m coming out with everything I got. This is everything I ever wanted. I plan on making it my moment, and I’m going to keep proving people wrong.”

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoBoxing Notes and Nuggets from Thomas Hauser

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoEkow Essuman Upsets Josh Taylor and Moses Itauma Blasts Out Mike Balogun in Glasgow

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoNewspaperman/Playwright/Author Bobby Cassidy Jr Commemorates His Fighting Father

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoA Night of Mismatches Turns Topsy-Turvy at Mandalay Bay; Resendiz Shocks Plant

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoSam Goodman and Eccentric Harry Garside Score Wins on a Wednesday Card in Sydney

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 326: A Hectic Boxing Week in L.A.

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoHiruta, Bohachuk, and Trinidad Win at the Commerce Casino

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoDavid Allen Bursts Johnny Fisher’s Bubble at the Copper Box