Book Review

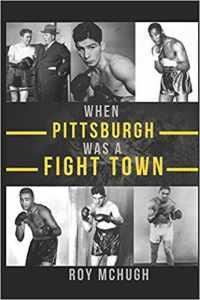

Roy McHugh’s Monument

A Review of When Pittsburgh Was a Fight Town (2019)

Roy McHugh never met Harry Greb. He was eleven when the Pittsburgh Pandemonium passed away on a rainy day in 1926, and it’s fair to say he just missed him. He was, however, pals with Greb’s pal and sparring partner Cuddy DeMarco, which means he has one degree of separation to my fifteen from the greatest fighter of the last hundred years. As if that wasn’t enough, he also shook the hand of Mike Gibbons, whose hands had been bouncing off Greb’s head just a few years earlier at Forbes Field. McHugh was a child then and still wiping the stars out of his eyes when a package arrived at his door. Inside was a pair of boxing gloves and a handwritten note by Gibbons himself:

Put on these gloves and do your stuff,

Prepare for the days when the roads are rough;

You’ll get a little groggy, but just give life an uppercut.

Those gloves and that note sparked a lifelong passion for fighting and writing. “Some of the other neighborhood kids helped me wear out the boxing gloves,” he told me. His last bout was a “bare-knuckle affair” on a thoroughfare in Alexandria, Louisiana in the summer of 1945. McHugh was stationed there with his company where he served as a machine gun instructor. Did he win? “I thought I was leading on points when the M.P.s broke it up after a minute or so,” he said. “They took both me and the other guy to the city slammer.”

He was already in print by then. His first byline appeared in Iowa’s Coe College Cosmos in the mid-1930s and when the war came, he was on staff at the Cedar Rapids Gazette. In 1947, he was hired by The Pittsburgh Press and spent more hours than anyone else crafting three columns a week for decades. His writing, the work of a perfectionist, is pressed gold. Elegant, economical, and yet rich with little-known facts and wry humor, it appears in a dozen anthologies, among them the 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1985, and 1986 editions of Best Sports Stories.

McHugh’s career opened during the Depression and didn’t close for seventy years give or take. He could write about any subject, though his favorite—the sweet science—was never in question. No boxing writer saw so much for so long or can exceed his talent for transforming a backward glance into living color. And his purpose was plain; he sought to reintroduce his heroes to successive generations, to remind a city increasingly infatuated with ball throwers in black and yellow about the radical individualists whose fists fanned the smoke and whose feats once dominated sports pages.

He tried retirement in 1983. “What are you going to do?” The Press sports editor asked him at the time.

“Nothing,” said McHugh. “Oh, I don’t know. Maybe I’ll become the biggest bum on Shiloh Street.”

“Would you consider writing a book—?”

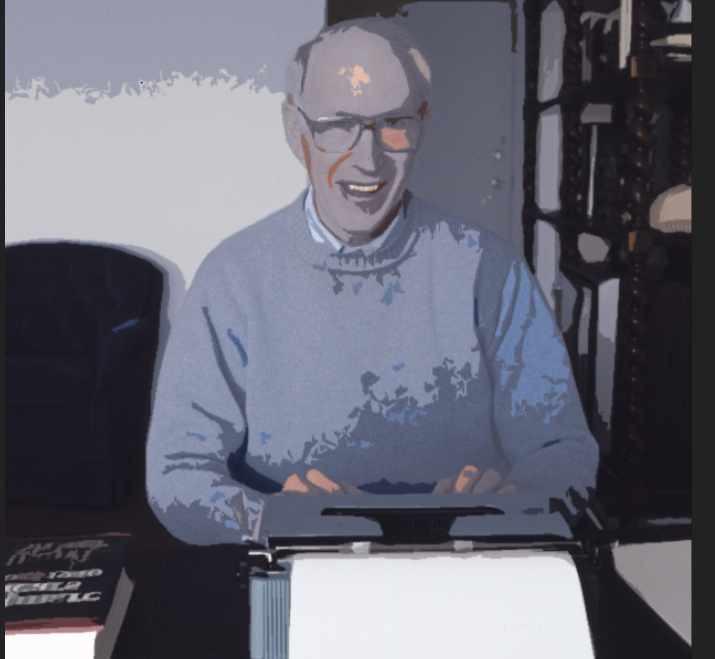

Over the past dozen years, McHugh’s vision deteriorated and his fingers stiffened with arthritis; his typewriter quieted, but was never quite put away. Meanwhile, Pittsburgh’s major dailies did no more than mention Greb’s name a handful of times. They needed reminding. In 2008 a full-page feature discussing Greb alongside Billy Conn appeared in the Post-Gazette. McHugh wrote it. He was 92.

Pittsburgh has since forgotten about Harry Greb. It hardly ever knew him.

Only weeks after he was buried at Calvary Cemetery, a delegation of citizens won the mayor’s support to erect a statue in his memory in Friendship Park, not far from where he was born. It ran into opposition when a few members of city council scoffed at the idea of honoring “a pugilist.” “No proper thinking person would be for it,” griped one of them, “a great majority of the people would be against it.” The plan was forwarded to the art commission, and stalled out.

In August 2018 a petition appeared online to memorialize Greb by renaming the Highland Park Bridge in his honor. The goal was modest—1,000 signatures. It stalled out at 359. Pittsburgh’s population is 301,048. I was downtown in the lobby at the Marriott City Center that summer, leafing through a travel guide book and scoffing aloud about who was not included in either the “Famous Pittsburghers” or “City of Champions” sections. Greb was not mentioned, nor was Conn, Charley Burley, Fritzie Zivic, Teddy Yarosz, or Frank Klaus. The councilman, it seems, was right.

On February 25, 2019 I got a message from Douglas Cavanaugh. “Roy passed today,” it said. He was 103. An introvert averse to accolades, he asked for no ceremony. His ashes are buried at Calvary Cemetery, near Greb and Conn.

Much—too much—was buried with him.

Four months later, he spoke.

When Pittsburgh Was a Fight Town is a 115,000-word monument to those pugilists he idolized during his living years. Much of it was written while he was in his eighties and nineties, which strongly suggests that McHugh had the longest literary prime on record. His mastery is evident immediately, in the preface, where he launches into a treatise of his adopted city’s history as a warm up.

Writing about history is more of a hardship than reading it but McHugh shows us how it’s done. He moves quickly to ward off narcolepsy, brushing aside widely-accepted inaccuracies one after another as if loosening his tie, ushering the reader back to a time when smoke and soot hung heavily in the air and only fools and tourists wore white shirts. “The very atmosphere affected behavior,” he remembers, and taps a spell on his typewriter to conjure up streetlights piercing the gloomy noon, open sewers, and rubbish in vacant lots. And he’s full of surprises. Outsiders complained, he said, not the natives. “They liked the lurid red glow of the steel mills at night. They liked the smoke, because smoke meant jobs.” He speaks with the authority of one who was there, and sets you on a sidewalk or at ringside and lets you eavesdrop on conversations—often one of his own.

You leave these encounters edified. Was Greb really the light puncher of internet boxing forums? Jack Henry, who carried Greb’s spit bucket, said his relative dearth of knockouts is better attributed to sadism. “He’d beat the hell out of guys,” he said. “When they’d start to fall, he’d grab them and hold them up.” Another insider confirmed this. He told McHugh that Greb “never showed mercy to anybody he trained with.”

Did you know that Conn never wore a mouthpiece until Fred Apostoli persuaded him in gruntspeak while socking his jaw during a brutal bout in 1939? Me neither.

Did you know that Burley was offered a shot at Zivic’s welterweight crown? The terms are on page 151, which happens to be what Burley weighed when he stopped a heavyweight in 1942. How did he manage that? McHugh asked him for you. He met the great uncrowned champion when he was a novice filling in for The Press’s regular boxing writer before Burley faced an up-and-comer at the Aragon Gardens. McHugh dismissed Burley as over the hill and then Burley sent the up-and-comer into a slumber in the first round. “I apologized to him,” McHugh admits. “Get me a fight with [middleweight contender Lee] Sala and we’ll be friends,” said Burley. McHugh tried and saw first-hand what the problem was.

If you were watching TCM’s Noir Alley in May, you’ll remember Joan Blondell in Nightmare Alley. McHugh tells us that she wrote letters to Billy Soose “almost every week” after he enlisted in the Navy. If you watched WWF wrestling in the 1970s and 80s, then you’re familiar with Bruno Sammartino. In the 1950s, he was showing promise as a boxer in Pittsburgh and so was hooked up with Whitey Bimstein in New York. “And then one day,” (McHugh again) Sammartino was told to lace ’em up to spar with a scowling hulk fresh out of the clink. Sammartino went five rounds with Sonny Liston at Stillman’s Gym.

Curious about what happened? Buy McHugh’s book. Boxing history buffs be advised, there is much in it you don’t know. Read it and be humbled. I know I was.

The book ends with McHugh in the presence of Muhammad Ali in the early 1960s and in 1980—at the bookends. He stands unblinking in the brilliance, bemused as the twenty-year-old contender introduces himself in his hotel room by rolling out from under a bed; bemused and out of place as he accompanies him on a date to a Louisville bowling alley. We see McHugh looking up when beckoned (“You ready to write?”) and meticulously writing down lyrics.

They all knew when he stopped in town

Cassius Clay was the greatest around…

“Pretty good, ain’t it?” said the poet, eagerly.

(It wasn’t, yet, though McHugh was too polite to tell him so.)

When he met Ali again twenty years later, the ex-champion was at his Deer Lake training camp, 250 miles east of Pittsburgh and sporting an ill-advised mustache during an ill-advised comeback. He was overweight and slurring his words between gulps of grapefruit juice. But he recognized the diligent little man with the pen and pad.

“He never wanted to be the star of his work,” writes Cavanaugh, his friend and the book’s copy editor, “and remained a humble scribe from the beginning of his career until the end of his life.” Even so, McHugh reveals his worth, despite himself, in the early prints of his posthumously-published book. He did it in a most unexpected way. While reading, I noted double commas and rogue colons appearing here and there on the pages. “His original manuscript had absolutely no mistakes,” Cavanaugh told me. “I was mortified to get the report that there are a bunch of typos in there.” It wasn’t his fault. It wasn’t McHugh’s either, not really. “Apparently, Roy went back and tinkered a bit,” Cavanaugh continued, “but I didn’t know it. His eyesight had been so bad at that point that it allowed for typos.” At that point, he was a hundred years old.

When Pittsburgh Was a Fight Town is his monument—a monument that carries names forward, names that must never be allowed to recede beyond reach and recognition, names that now include Roy McHugh.

______________________

Available now on Amazon

Original photograph (1984) courtesy of The Pittsburgh Press.

Springs Toledo is the author of Smokestack Lightning: Harry Greb, 1919 (2019).

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 days ago

Featured Articles3 days agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival