Featured Articles

50 Years in Boxing: Philly’s J Russell Peltz Shares His Golden Memories

When he was a 22-year-old kid embarking on a boxing journey that might have ended almost as quickly as it began, J Russell Peltz – with big dreams and not-so-deep pockets — never considered issuing anything as portentous as a mission statement. But if he had, it might have read something like this:

You know what the secret is to surviving as a boxing promoter? Making good matches. It’s that simple. If you want to make a good match, you make a good match. If you want to get your guy a guaranteed win, pair him easy. But don’t charge your customers $50 or $75 to watch that garbage.

Peltz said that for a story I did for the Philadelphia Daily News in November 2012. Making good, competitive and entertaining matches has always been the touchstone of his remarkable longevity in a cannibalistic sport which tends to devour those not smart enough or tough enough to survive in the long term. But while Peltz has known both flush and lean times, adapting as necessary at junctures along the way, the guiding principle of Philly boxing’s onetime “Boy Wonder” has never changed. It is why he has been inducted into seven Halls of Fame and outlasted a host of competitors who sought to knock him off the local throne upon which he remains firmly ensconced. He said he still gets as much of a charge from seeing a dandy scrap as he did when, for his 14th birthday, his father took him to his first live fight card. What young Russell – the J in his full name, as was the case with the S with former President Harry S Truman, stands for nothing — saw that night left an indelible impression. Somehow, some way, he would make the fight game more than an avocation, but his life’s work.

Peltz’s first foray into the business end of boxing came on Sept. 30, 1969, when middleweight Bennie Briscoe needed just 52 seconds to dispose of Tito Marshall at the Blue Horizon, the main event of a card that included such young, future Philly legends as Eugene “Cyclone” Hart and Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts. It was an astounding debut for Peltz, with a standing-room-only crowd of 1,606 jamming the 1,300-seat arena.

There would, of course, be some whiffs along with the home runs before Peltz evolved into an entrenched, iconic figure in his hometown’s fight scene. Both the hits and the misses have contributed to making him who and what he is, the sum total of his five-decade love affair with the sweet science to be celebrated first at an invitation-only Golden Anniversary Reception on Thursday, Sept. 26, at the 2300 Arena in South Philly, preceding an eight-bout fight card at the same site on Oct. 4. Dubbed “Blood, Sweat and 50 Years,” that show – topped by a six-rounder pitting Victor Padilla (5-0, 5 KOs) of Berlin, N.J., by way of his native Puerto Rico, against Romain Tomas (8-2, 1 KO) of Brooklyn, N.Y. — will be staged by Raging Babe Promotions’ Michelle Rosado, a Peltz protégé. In addition to her mentor being the guest of honor, Peltz also is serving as matchmaker, a role for which he has justifiably gained much distinction.

It also might be the last time Peltz acts in that capacity, an indication that, just possibly, his 50-year anniversary in boxing might mark the beginning of the end of a storied career which he has been contemplating for some time. In that same November 2012 Philadelphia Daily News story in which he issued his ersatz mission statement, Peltz dropped hints that nothing, not even his involvement in boxing, can last forever.

“At points in the last five years, I’ve thought about retiring,” he said then. “I think about it now. I’m certainly not going to be doing this when I’m an old man. I don’t want to be doing this when I’m an old man.

“Really, I don’t know how much longer I’ll go on. Maybe I’ll get out when I’m 70 or 71. But whenever I think about quitting, I become involved with a fighter (who piques his interest).”

And now? Peltz turns 73 on Dec. 9, hardly an old man in terms of his energy and enthusiasm, but he is inarguably a senior citizen according to the Social Security administration.

“I don’t think I’ll be making matches after Oct. 4,” he said when contacted for this story. “I don’t have the temperament to do it anymore. I can’t tolerate the mentality of a lot of the fight people in Philly who don’t want to fight other Philly guys. That’s what made Philly the fight town that it was.

“I go around the house screaming and Linda (his wife) says, `I know why you’re screaming. You’re making matches again. You said you weren’t going to do it. When you do it, you’re impossible to live with.’

“I think what I want to do is to advise fighters, maybe manage fighters. Some of these kids today deserve their own careers rather than being served up as cannon fodder for top prospects for Top Rank, Golden Boy, Eddie Hearn and PBC.”

If Peltz does in fact hew to that somewhat altered philosophy, it would in some ways represent his coming full circle. Despite whatever misgivings he might harbor about professional boxing as presently constituted, he has always gotten an adrenalin rush from identifying and nurturing young fighters who remind him of the twentysomething firebrand he used to be. For all his musings about stepping aside, it would stun no one if he elected to keep on keeping on in the manner of Top Rank founder Bob Arum, an occasional associate who is 87 and still active, or his dear, departed friend Don “War a Week” Chargin, a licensed promoter in California for a record 69 years who was 90 when he passed away on Sept. 28, 2018. Chargin was another staunch proponent of the concept that fans deserved real fights, tough fights, and not setups designed to make protected house fighters look better than they probably are.

But regardless of what the future holds for Peltz, the past 50 years make for an improbable tale even in a sport where improbable tales are more the norm than the exception. It starts even in advance of the Briscoe-Marshall bout that the golden anniversary celebrants will cite as his official launching point.

Then a sports writer for the now-defunct Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Peltz had been squirreling away portions of his salary for the express purpose of establishing enough of a nest egg so that he could take the plunge. Toward that end, he says he spent “countless hours” in the Blue Horizon office of building owner and veteran fight promoter Jimmy Toppi, pestering the older man with questions about how to make his dream of doing what Toppi did a reality.

Two weeks before Briscoe-Marshall, Peltz resigned as a full-fledged member of The Bulletin sports staff, although he did keep his hand in as a one-night-a-week, part-timer as a hedge against possible disaster on fight night.

“I had saved up about $5,000, which was a lot of money back then for someone my age,” Peltz recalled. “The woman who became my first wife asked me, before we got married, ‘What makes you think you can do this?’ I told her it’d take me about six months to blow the five grand, but then I’d have this great scrapbook to show my kids one day about the time their daddy was a boxing promoter.”

Not that he completely went through his savings, but Peltz – whose contingency plan was – gulp – to go back to sports writing if the grand experiment came a cropper – hit some dry holes after Briscoe-Marshall. He was obliged to seek and receive a loan of between $2,000 and $3,000 from his dad, Bernard, to help underwrite his second year as a struggling fight promoter. It also didn’t help that Peltz’s wife, he said, absolutely hated boxing and was providing no moral support on the home front.

“I told my father that if I couldn’t pay him back by the end of the season, I’d just go back to the newspaper business,” Peltz said. “I was making $7,500 a year at The Bulletin. My first year putting on shows at the Blue Horizon I cleared $4,600 from September through May. But in the summer of 1970, I accidentally found out that Bennie Briscoe’s contract was for sale. I knew that was my ace in the hole after I asked my brother-in-law (Arnold Weiss) to buy Bennie’s contract, which he did.”

But even that ace in the hole –- Briscoe, who three times fought for the middleweight championship of the world and appeared 45 times in all on Peltz-promoted or co-promoted cards – might not have been enough to keep Peltz’s nascent operation moving forward. What was needed was some positive publicity, which he got from then-Daily News sports writer Tom Cushman.

“If it hadn’t been for Tom Cushman, I never would have made it,” Peltz noted. “I met him when he came east to cover Temple (Peltz’s alma mater) in the All-College (basketball) Classic, which they held every December in Oklahoma City. I was there covering for The Bulletin and The Temple News. We got friendly. So when I decided to become a boxing promoter, Tom, who by then was at the Daily News, thought it was really cool that a 22-year-old kid would do that. He gave me a load of good press, even more than I got at my own paper.”

There would be other puzzle pieces that fell into place at precisely the right moment. Now reasonably established if not exactly getting rich doing shows at the Blue Horizon and The Arena in West Philly, Peltz got his shot at the big time – or what seemed to be the big time – when in 1973 he was approached about becoming the director of boxing at the 18,000-seat Spectrum, home of the NBA’s 76ers and NHL’s Flyers.

“I got a call late in 1972 from Lou Scheinfeld at the Spectrum,” Peltz recalled. “Monday nights were dark there and it was costing them money to have nothing going on. I met with the Spectrum people and they hired me for a salary against a percentage of the profits. The first year we ran 18 shows and lost money on 16 of them. We were hemorrhaging money, and it had nothing to do with Monday Night Football in the fall.

“Allen Flexor, who was the Spectrum’s vice president and comptroller, asked me to go to lunch, ostensibly to fire me. We talked for a while and I said, `If I can get the Philly guys to fight each other, I can turn this thing around.’ He basically said `OK, we’ll give you some rope and see what you can do.’ I put up signs in all the gyms in the city about a meeting to be held at Joe Frazier’s Gym on such-and-such a night in December. I wanted all the managers and trainers to come to that meeting, and 50 to 60 of them showed up. I said, `Look, the Spectrum has the Sixers, the Flyers, concerts, Disney on Ice, the circus. They don’t need us. Unless you guys start fighting each other, we’re going to go back to The Arena, and I know you don’t want to do that.”

Given the depth and quality of Philadelphia fighters at the time – a mother lode of talent with Briscoe, Hart, Watts, Willie “The Worm” Monroe, Stanley “Kitten” Hayward, Matthew Saad Muhammad, Jeff Chandler and other main-event-worthy locals – it was a plan that could not have failed. But it might have, had not one influential dissenter passed away unexpectedly.

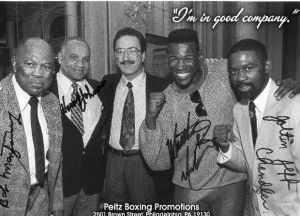

left to right: Bob Montgomery, Harold Johnson, Peltz, Matthew Saad Muhammad, Jeff Chandler

“If Yank Durham (Frazier’s manager and trainer) hadn’t died in September of ’73, we would have had big problems because he was against Philly vs. Philly,” Peltz continued. “But Eddie Futch took over after Yank died and he knew the value, coming from the Olympic Auditorium (in Los Angeles) when all those great Mexican fighters fought each other. Eddie said, `Let’s make Willie the Worm against Cyclone Hart,’ which was a monster show with a turnout of 10,000-plus. From the beginning of 1974 until the end of ’78 the Spectrum was as big as (Madison Square) Garden and the Forum in Inglewood, Calif. Everybody wanted to fight at the Spectrum, and everybody did.”

But when the casinos in Atlantic City opened later in the decade, that siphoned from the Spectrum’s fan base to the point where the fight dates diminished, along with the massive crowds. But, Peltz says, wistfully, “Those last five years there were wonderful. I got a bonus every year.

“When Briscoe fought (Marvin) Hagler, it was a 10-round fight and we had a crowd of 15,000. It wasn’t for some bulls— title, either. We had good fighters and they weren’t afraid to fight other good fighters.”

There were occasional missteps for Peltz, too, which probably was to be expected. “A lot of good fighters slipped through my fingers,” he said, citing Hagler and Buster Douglas as two he might have signed to promotional deals before their price tags exceeded his budget. “You learn as you go, but you never stop making mistakes.”

So, if he had to choose his single best moment in boxing, and the worst experience, what would they be?

“You always fall in love with your first fighter,” he said of his continuing devotion to Briscoe, who was 67 when he died on Dec. 28, 2010. “That’s never going to change.

“My most memorable moment was Bennie’s fifth-round knockout of Tony Mundine on Feb. 25, 1974, at the Palais de Sport in Paris. “Mundine, an Australian, was like the heir apparent to (middleweight champion Carlos) Monzon. He was a certified star, who had beaten Emile Griffith and Max Cohen in Paris.

“I saw Reg Gutteridge (a British sports journalist who was doing color commentary for the telecast) in the hotel lobby before we left for the arena. He said, `I don’t get it. Mundine is the toast of Paris. He can name his price to fight Monzon. Why would he tune up with Briscoe?’

“It was a monster fight, as big as it could be without it being for a world title when world titles really meant something. Just a magical night. I was shooting film from the top row and when Bennie finally got him out of there, the camera was shaking because my hands were shaking.”

Another significant plus, both on the professional and personal levels, was Peltz’s marriage to second wife Linda, who understood she would have to share her husband with boxing and hasn’t minded it at all. It’s amazing what domestic tranquility can do for a fight promoter’s peace of mind at the office and at ringside.

“We started dating in February of 1976,” Peltz said. “Her first fight was the rematch between Briscoe and Hart, which drew 12,000 people to the Spectrum. She sat with me in the first row.

“Everybody loves Linda. People say, `How bad can Russell be? Linda married him.’ And there’s no doubt she’s smoothed over a lot of things through the years. She brought together some people in boxing I just couldn’t talk to, just like she brought together some estranged family members I hadn’t spoken to in years.”

The giddy highs of Briscoe over Mundine, and spousal bliss, were countered by what Peltz said remains his greatest disappointment in boxing, even more painful than the horrendously unjust decision that went against Peltz’s fighter, Tyrone Everett, in his Nov. 30, 1976, challenge of WBC super featherweight champion Alfredo Escalera at the Spectrum, a split decision that remains high on the list of boxing’s most outrageous heists.

“The low point of my career had to be my relationship with ESPN when I was hired to be their director of boxing (in October 1998),” Peltz said. “It was just a scam, a setup. I lost most of my power pretty quickly. At first I thought, `After all these years of making good fights, it’s finally paid off. They’re hiring me because they know I’m going to make more good fights.’

“Three or four months into the deal the people who hired me moved on to ABC and I was left to deal with the ol’ boys club which essentially turned me into an errand boy. I hung in there until the fall of 2004, but after six to eight months it was just agony. I got blamed for a lot of bad fights that were on ESPN I had nothing to do with.”

Peltz needn’t worry about any blame he might have received when weighed against the credit he has deservedly gotten. Seven Halls of Fame are proof enough that he has done far more right than wrong, and that some Boy Wonders can age gracefully with their place in history forever secured.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review2 weeks ago

Book Review2 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRahaman Ali (1943-2025)

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoTop Rank Boxing is in Limbo, but that Hasn’t Benched Robert Garcia’s Up-and-Comers