Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Flyweights of All Time: Part Two 40-31

The Fifty Greatest Flyweights of All Time: Part Two 40-31

In Part One we talked about Brian Viloria and his momentous confrontation with Juan Francisco Estrada. Their fight denotes their relative standings. As a general rule each chapter of this series, from heavyweight to bantamweight, will produce an entry or two where two of the fighters listed have actually met in the ring.

At flyweight, every entry appraises two fighters who met in the ring.

Some huge flyweight contests have failed to materialize. We meet a fighter in this installment who made a very impressive career out of failing to fight the best. Nevertheless, I am struck by how often top fighters from this division clashed and how often those vying for spots in the Top Fifty have settled their differences in the ring. Flyweight is overlooked by boxing history but it is a fact that the very greatest flyweights had a tendency to butt heads.

Despite being faster than the denizens of every other division, despite, as a rule, being the most technically sure, flyweight is under-celebrated both in boxing’s past and in boxing’s now. What this means is there is less money to sustain mediocrity. So, the best meet the best more often.

The men listed here are some of the best.

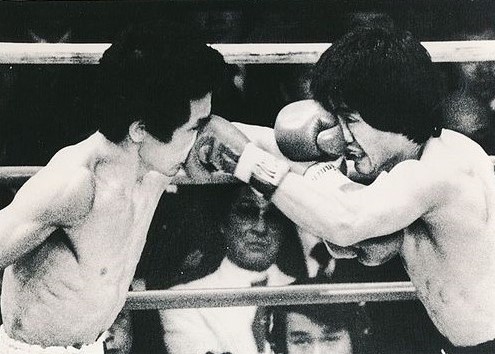

#40 – Fighting Harada (1960-1970)

Fighting Harada represents terminal velocity for a box-swarming style. On film he only has Joe Frazier and Henry Armstrong for company and with available footage of Hank so limited, Harada comes off a little better compositely. He was elemental.

But his best work came at bantamweight. Thickening out of his youth, he had time to do only a minimum of damage to a division that breathed a sigh of relief at his passing. What gets him onto this list, though, is his best win, a title-winning effort for the ages against the champion Pone Kingpetch.

Like Rocky Marciano before him, this early iteration of Harada always had something on his opponent, his head, his wrist, the knuckle of his glove; and like Marciano before him he lived and breathed the pressure he brought with a fire unseen in the division’s filmed history. He often missed but when he missed he tended to be bringing something behind. What sets him apart – arguably – from Marciano and Frazier and Armstrong is his jab, which was as excellent and as busy as any fighter of his type from any division you care to name.

All of this can be seen in his woefully underappreciated first fight with Kingpetch who succumbed in the eleventh while propped in his own corner, alarmingly abandoned by the referee while Harada battered him. It was a brilliance.

Harada was narrowly defeated in an immediate rematch and the win over Kingpetch is far and away his best (next may be his six-round defeat of a youthful Hiroyuki Ebehara). His title reign was comprised of exactly zero successful defenses, but so wonderful was he against Kingpetch and that result was so suggestive that Harada slips in here in front of men with more concrete reasons for a higher ranking.

I suspect none of them could have defeated him in the ring.

#39 – Erbito Salavarria (1963-1978)

Erbito Salavarria, who wore the brooding good looks of a Hollywood matinee idol, held the flyweight world championship for the whole of 1971 and 1972, snatching it from no less a figure than Chartchai Chionoi in December of 1970 before losing it to the wrecking ball Venice Borkhorser early in 1973. He defended it successfully against top flyweight Susumu Hanagata, whose hopes he dashed no fewer than three times, and the near legendary Betulio Gonzalez.

So far, so good, and considering he also defeated solid contenders like Berkerk Charvanchai and Vincente Pool, he has the paper resume for a higher ranking; but the devil, as always, is in the detail.

Salavarria’s contest with Gonzalez, a desperate split draw, was a bad-tempered affair and one of the most controversial title fights in flyweight history. After the contest – marred by conflicting perspectives on the veracity of the scorecards – Salavarria had a bottle containing “honeyed water” removed from his corner by officials. This water was later reported as containing amphetamine.

It is unclear what should be made of this. On the one hand, Salavarria has maintained his innocence throughout, claiming that the amphetamine was planted by Venezuelan authorities in order to protect their beloved Gonzalez. On the other, the claim was upheld by the WBC, hardly a bastion of incorruptibility but the best we have by way of an arbiter.

That’s seen me drop Salavarria to the lowest berth his resume can stand. But Salavarria unquestionably had the goods. His second victory over Hanagata, who was absolutely legitimate, came years after his controversial draw with Gonzalez and was so close as to be scored either way; but fought in Japan it is also the case that Salavarria was almost certainly clean, thereby proving his countering abilities and late excellence born of true stamina was a valid representation of his ability.

#38 – Mark Johnson (1990-2006)

The disturbing truth about Mark “Too Sharp” Johnson is that he never defeated a top five opponent in his entire over-celebrated career. Johnson spent the mid-nineties waving around something called the World Boxing Board championship, thankfully now defunct, before picking up a slightly more respectable strap in 1996 which he defended seven times before departing for 115lbs.

And these are the numbers you tend to run into when you read about his career.

The number you tend not to read is “6”, which was the highest ranked opponent Johnson ever met, specifically a fighter named Arthur Johnson who he knocked out in one round in February 1998. Arthur was 17-3.

But Johnson was brilliant. There is no denying it. So, he ranks here higher than I feel he earned in the course of his career beating the likes of Alejandro Montiel (ranked seven), Alberto Jiminez (ranked ten) and Enrique Orozco (ranked seven). This was while missing out on the likes of Saen Sor Ploenchit, Miguel Martinez, Jose Bonilla, and most of all, Yuri Arbachakov.

The awful truth is, Johnson was probably good enough to beat all of these fighters and would have been embarrassed by none of them. As it is, his unbeaten status at the poundage and his brilliance on film makes him impossible to ignore.

But his is another potentially great career sacrificed to inexplicable alphabet mandatories.

That costs him a spot in the top thirty.

#37 – Emile Pladner (1926-1936)

I maintain a special admiration for boxing centurions, men who have found a way to win no fewer than 100 fights. It’s a special number and one rather understated now by boxing for one very good reason: it will never happen again.

So, men like Emile Pladner should be lauded for this special achievement.

Also special was his 1928 victory over Izzy Schwartz, who opened our own half-century at #50. Pladner sliced him open both figuratively and literally, finding his way past his opponent’s defences in the third and thereafter abusing him so thoroughly that Schwartz left the ring a bloody mess.

He was more admirable still is his 1929 defeat of Frankie Genaro, one of history’s greatest knockouts.

Genaro, probably, had begun to slip by the time he met with Pladner, but he was already a flyweight immortal. What Pladner did to him was absurd. Reportedly always a little skittish at the first bell, he was somewhat startled by Genaro’s early two-handed charge, stepped close, rattled the American’s teeth with a right, and then landed a devastating uppercut somewhere on Genaro’s body. Some say liver, others say below the heart and maddeningly, the scraps of surviving footage do not settle the issue.

Joe Jacobs, who was managing Genaro at the time, claimed it landed considerably lower, indeed, even below Frankie’s belt, but this was dismissed outright by the Associated Press: “To ringside spectators the knockout blow appeared to land six inches above the belt.”

Whatever the specifics of the punch, Genaro dropped like a stone and writhed in agony at the feet of the referee. It was the only time anywhere near his prime that he heard “ten”.

Pladner dropped the title in the rematch with Genaro – after landing two low blows. He bid “adieu!” to flyweight, leaving behind an incomplete, perhaps even unsatisfactory legacy.

#36 – Black Bill (1920-1931)

Eladio Valdes, unfortunately renamed “Black Bill” by a promotional team in search of higher ticket sales, stuffed 160 fights into an eleven-year career. That’s an average of more than one combat every month. A cast-iron jaw and a dearth of power also sent the number of rounds he boxed through the roof.

Never a ticket-seller despite the change of name, it took a winning streak of nearly thirty fights to land him in the ring with a champion, and he was presented with a beauty: Midget Wolgast who out-pointed him over fifteen in March of 1930. His sight deteriorating, he lost four of his next five and went the way of all those who draw too much dark water from the well within. A struggling shadow of his former self, depression sent him to an early grave within three years of his retirement.

Before that: he dominated a series with Corporal Izzy Schwartz, winning four of six closely contested fights in one of the definitive flyweight series for this era; took a single victory in the losing end of another epic five-fight series with Willie Davies; and defeated contenders Phil Tobias and Johnny McCoy.

It’s good. It’s a strong resume but an ill return for a fighter who fought so many contests. In truth, his absurd and difficult schedule and his unfashionable standing – and his admitted limitations as a fighter – resulted in his suffering twenty-four losses and his being frozen out of the title picture. Difficult patches afflicted him, especially between 1925 and 1927.

Still, that hot-streak, for all that it ended in defeat at the hands of the genius Wolgast, cements his place here among some great contenders and the lesser champions.

#35 – Johnny Buff (1917-1926)

Johnny Buff, the one-time world bantamweight champion out of New Jersey, has proven something of a difficulty for me. He inexplicably pops up in the IBRO all-time great top twenty, at the #14 spot no less; suffice to say here that there is no possible reason for his ranking so highly under my criteria and it is difficult to imagine any system that would make such a lofty position justifiable.

Buff did do some interesting work at fly before and after winning his bantamweight title, however, and it certainly deserves a second glance.

He turned professional at bantamweight in 1917 and did most of his best work at that poundage into the early 1920s culminating perhaps in a very good draw against Pete Herman. He then seems to have spent some months sitting down on the flyweight limit in order to generate some title tractions. This is the key in appraising his flyweight legacy.

In a final eliminator for the American flyweight title, a title that carried much more weight then than now, he defeated the favored Frankie Mason over fifteen rounds in New York City, clambering from the canvas after an early knockdown to out-fight an opponent who managed to win as few as two rounds according to some ringside reports. It was a savage, vicious performance, and perhaps Buff’s best. He then took the vacant title against Abe Goldstein, a capable and storied fighter but another one who would make his true championship bones up at bantamweight; solid defenses against Young Zulu Kid and Eddie O’Dowd followed before Pancho Villa battered the title out of him in 1922.

By that time, Buff was once again campaigning at bantamweight, where victories over Pete Herman and Jackie Sharkey made him a fighter of real note – but he never again won a meaningful combat at 112lbs where he lost crossroads fights to Frank Ash and Joe Lynch.

All of this adds up to enough to scrape him into the top forty, but arguments for a higher berth seem reliant upon bantamweight honors.

#34 – Venice Borkhorsor (1968-1980)

Venice Borkhorser is perhaps more famous for the thumping damage he did with his menacing punches and his menacing presence up at bantamweight, not least because he spent most of his career fighting above 112lbs; big even at 118lbs, he was huge for a flyweight and would remain so even today.

This in part brought him the championship of his native Thailand and in late 1972 and early 1973 brought him pre-eminence in a division he would leave forever just months later.

His clash with the excellent Mexican Betulio Gonzalez in September 1972 was probably his peak. He stalked, battered and eventually broke the proud champion, leaving him stricken to the body and bleeding from the face. Gonzalez quit. Borkhorsor, though he could not sustain his career at 112lbs, was a steam-fired engine running on hatred for the days he managed to crush his musculature into a weight division that stretched at the seams to contain him.

Just a few months later (and time was of the essence), Borkhorsor was matched with Erbito Salavarria with lineage on the line. Salvarria did not quit, but he was harassed, harried, cut, pushed back and according to the Thai officials, did not win a single round against a Borkhorsor who battered a second world class fly into non-resistance.

Gonzalez ranks above Borkhorsor but the details of their contests suggest that he could never have beaten him in a dozen efforts. But Borkhorsor never fought at the poundage again, departing for bantamweight where he continued to box with the same menace though with less devastating results.

#33 – Salvatore Burruni (1957-1969)

Salvatore Burruni was the idol of Italy for a short spell in the 1960s, demonstrating the art of the most direct form of boxing in out-thugging champion Pone Kingpetch in 1965, backed by a rampant Roman crowd. Burruni gambled it all on a violent frontal assault, eschewing the jab in favor of an absurd smorgasbord of leads that included a trailing uppercut and numerous over-the-top hooks. But Burruni’s fight-plan was more detailed and nuanced than just that. He squatted in the attack, extenuating his height deficiency and opening up Kingpetch’s heart for a reverse one-two finishing in a straight left. He racked up the early rounds to make himself unassailable late in the fight when he inevitably began to tire. Kingpetch, at that point in his career, was there to be taken, and indeed had been taken before – but he had always won a return. Burruni had beaten him so thoroughly that a rematch seemed redundant.

Instead he fought the Australian prospect Rocky Gattellari, an understandable decision from a monetary perspective and a reasonable one from the fistic perspective. Gattellari, though inexperienced, was ranked at #5 by The Ring magazine. This wasn’t good enough for the alphabet organizations who immediately stripped him.

Burruni then defended his lineal title against former victim Walter McGowan and was summarily defeated by decision in London in 1966. He continued to explore bantamweight, where he was never a serious force.

He leaves behind a decent resume made up of McGowan, Gattellari and Mimoun Ben Ali, the perennial fly and bantamweight contender, who he defeated for the European title in 1962. His victory over Kingpetch, however, is the jewel in his crown. It remains perhaps the most perfect example of a face-first, bet-it-all assault on a champion that resulted in the passing of the torch, echoed by, among others, Ricky Hatton’s 2005 defeat of Kostya Tszyu.

#32 – Chan-Hee Park (1977-1982)

Those paying close attention and of a certain type of mind may have noticed that there is a pattern emerging in the low forties and high thirties, specifically a clutch of fighters who have one very significant divisional win backed by another good victory in the flyweight division. This description fits Chan-Hee Park, the Korean world flyweight champion in 1979 and 1980, like a glove.

Park’s marquee win was over all-time great and contender for the #1 spot, Miguel Canto. Nor was Park fighting some busted version of Canto but rather he was the man who unseated the then champion from the throne, breaking a streak which was arguably the most impressive in the history of the division.

On paper it’s a stuck-on nomination for one of the greatest wins in the history of the sport. In reality, Canto was far from the Rolls Royce that used to glide around the ring dictating pace with one of the greatest of left hands. Still, Park beat him out of sight, an impressive achievement.

Three months later he became the first man to stop the formidable Mexican contender Guty Espadas in a short and brutal encounter; two more defenses against limited opposition stiffened his championship reign a little and then Park ran into a roadblock named Shoji Oguma.

#31 – Shoji Oguma (1970-1982)

Shoji Oguma’s paper record of 38-10-1 is less than overwhelming but he must be included, and must be included above Park, for no better reason than he defeated the Korean no fewer than three times.

The result of their first fight, fought in Seoul, Korea, was indisputable, as Oguma began throwing left-hand leads from his southpaw stance to dent Park’s great chin and finally take him out in nine hard rounds. An ultra-aggressive fighter, Park began an inevitable wind-down in a long fight, a factor that Oguma exploited mercilessly in their second and third contests, the second a desperately close split decision that could have gone either way, the third, total carnage, both fighters finishing smothered in blood, Oguma taking another disputed, narrow decision.

Defeating Park the first time made Oguma the world’s champion and the second and third were primo defenses; Sung Jun Kim, ranked five, made for a quality third defense before Oguma shipped the title to Antonio Avelar, who knocked him out in heartbreaking circumstances.

What makes Oguma a little special is that this was actually his second run at the problem. He had been a major force in the division once before, in the early seventies. There lies the beginning of another extraordinary series in which Oguma met Betulio Gonzalez, another excellent flyweight and one we will be hearing from soon. Oguma went around with him four times. His reward was two losses, a draw and a single victory over fifteen rounds in October of 1974. That brought Oguma a strap and although it was immediately scooped up by Miguel Canto, it makes him some sort of champion in two different decades. Worthy, perhaps, of a higher spot; those losses peg him back a bit.

But it takes a special legacy to demote Oguma from the top thirty. We will be meeting some of the men that keep him out next week.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds