Featured Articles

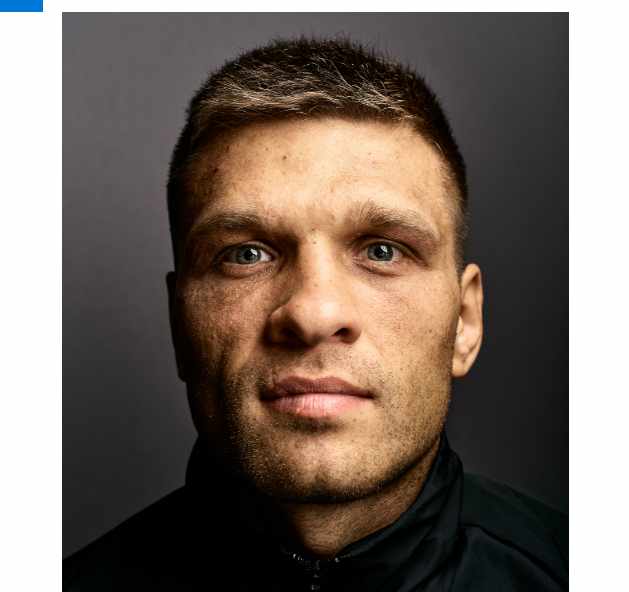

Sergiy Derevyanchenko and the Harsh Reality of Boxing

When Oscar De La Hoya was nearing the end of his storied ring career, he offered a stark assessment of the risks inherent in the trade he had chosen.

“I hate getting hit,” De La Hoya said. “Getting hit hurts. It damages you. When a fighter trains his body and mind to fight, there’s no room for fear. But I’m realistic enough to understand that there’s no way to know what the effect of getting hit will be ten or fifteen years from now.”

Boxers are not like ordinary people. They court danger and have a tolerance for pain that most of us think we can imagine but can’t. That harsh reality was on display when Gennady Golovkin and Sergiy Derevyanchenko met in the ring at Madison Square Garden on October 5 in a fight that will be long remembered as a showcase for the brutal artistry of boxing.

Derevyanchenko, age 33, was born in Ukraine and now lives in Brooklyn. He had roughly four hundred amateur fights in the Ukrainian amateur system which gave him a wealth of experience but also put considerable wear and tear on his body. He turned pro in 2014 and, prior to facing Golovkin, had a record of 13 wins against 1 loss with 10 knockouts. The loss came in his one outing against a world-class opponent – a 115-112, 115-112, 113-114 split-decision defeat at the hands of Danny Jacobs at Madison Square Garden last year.

Derevyanchenko is soft-spoken with a brush haircut, often impassive face, and eyes that can be hard. He understands some English but prefers to have questions translated into Russian and answer in his native language.

“I don’t like to talk about myself,” Derevyanchenko says. “I’m a private person. The attention that comes with boxing is a double-edged sword. For the money it helps me make, the attention is good. But the loss of privacy sometimes, especially when I am out with my family, it is not so good.”

Golovkin, age 37, is well known to boxing fans. Born in Kazakhstan, now living in Los Angeles, he brutalized a succession of pretty good fighters like Matthew Macklin and David Lemieux en route to becoming the best middleweight in the world. But thirty months ago, Gennady struggled to win a narrow decision on points over Danny Jacobs at Madison Square Garden. Thereafter, he’d had four fights: gimme knockouts of Vanes Martirosyan and Steve Rolls and two outings against Canelo Alvarez. The first Golovkin-Canelo fight (which most observers thought Gennady won) was declared a draw. The second ended with a credible 115-113, 115-113, 114-114 decision in Canelo’s favor, the first loss of Golovkin’s ring career.

Golovkin-Derevyanchenko crystalized how bizarre the business of boxing has become in recent years.

Last year, the IBF stripped Golovkin of its 160-pound belt for not fighting a mandatory defense against Derevyanchenko. Then Jacobs beat Derevyanchenko for the vacant IBF title but lost to Canelo Alvarez in his next outing. Thereafter, the IBF stripped Canelo for not fighting a mandatory defense against Derevyanchenko despite the fact that Sergiy’s only win after losing to Jacobs was a decision over lightly-regarded Jack Culcay. Thus, Golovkin was fighting Derevyanchenko for the same belt he was stripped of for not fighting Sergiy last year.

If that sounds strange, the money being thrown around was stranger.

Traditionally, a fighter had to win one or more big fights before getting a seven-figure purse. But DAZN, ESPN, Fox, and Showtime are locked in a bidding war that has led to huge license fees that often bear no correlation to revenue generated for a network by its fighters.

DAZN (which has a multi-fight deal with Golovkin) wanted Golovkin-Derevyanchenko as the launching pad for the final quarter of its 2019 season. The network was already locked into a deal that would pay Gennady a reported purse of $7,500,000 in cash plus $7,500,000 in stock in DAZN’s parent company to fight on October 5. DAZN then leaned on promoter Eddie Hearn to contribute significantly to Derevyanchenko’s purse to bring Sergiy into the fold.

Thus it was that Derevyanchenko (a largely unknown fighter with thirteen pro victories on his resume and who had never beaten a world-class fighter) was rewarded with a purse totalling $5,200,000 to fight Golovkin. Training expenses, manager Keith Connally’s share, taxes, and whatever PBC took (Derevyanchenko is a PBC fighter) came out of that total. Still, very few fighters in history have had a payday approaching that number. A marketable belt was at stake, but the fight wasn’t even for “the” middleweight championship of the world (a title that presently resides with Canelo).

“I like the sport,” Sergiy said when asked about boxing three days before fighting Golovkin. “I like the business. The business is crazy now.”

It certainly is. And adding to the drama, there was no rematch clause. Win or lose, Derevyanchenko would be contractually free to fight any opponent on any network after fighting Golovkin.

There was no trash-talking by either side during the build-up to the fight. The only sour note came at a sitdown with reporters just prior to the final pre-fight press conference when Golovkin was asked one question too many about a possible third fight against Alvarez.

“All these questions about Canelo,” Gennady answered. “It’s your problem, not mine.”

Golovkin was a 4-to-1 betting favorite over Derevyanchenko. He and Sergiy had each fought on even terms against Jacobs. But styles make fights. And the feeling was that, while Gennady and Sergiy had similar styles, Golovkin did everything a little bit better. He hit harder, took a better punch, was a shade faster, and so on down the line. ESPN asked eleven of its boxing reporters to predict the outcome of the fight. Ten thought that Golovkin would win by knockout. The eleventh chose Gennady by decision.

But while few insiders predicted that Derevyanchenko would win, no one was counting him out.

The question most often asked when the outcome of the fight was discussed was whether Golovkin had slipped with age. And if so, how far? Also, Derevyanchenko was in the best condition of his life, having spent six weeks in California preparing for the bout at Victor Conte’s SNAC conditioning facility.

This was Sergiy’s chance to prove that he belonged at the table with boxing’s top-echelon middleweights.

“Gennady has been a great champion but his time is coming to an end,” Derevyanchenko prophesied. “I want to be the one who makes it come to an end.”

Wearing a black Nike track suit with white trim, Derevyanchenko arrived in his dressing room at Madison Square Garden on Saturday night at 8:20 PM.

The room was roughly thirty feet long and twenty feet wide with a linoleum floor styled to look like hardwood planks. Ten folding cushioned metal-frame chairs were set against the walls. A two-seat, green imitation-leather sofa fronted a large flat-screen television mounted on the wall opposite the door. A college football game – Oregon vs. California – was underway.

Some fighters – Manny Pacquiao for one – like lots of action in their dressing room. Ricky Hatton’s dressing room was a mad cacophony of music and dancing from the moment he entered until he left for the ring.

Derevyanchenko prefers calm and no distractions. For the next two hours, he was remarkably quiet and self-contained. Except for manager Keith Connolly, no one would even look at a cell phone. From the moment Sergiy entered the room until he walked to the ring, everything was businesslike and low-key.

After leaving the room briefly for a pre-fight physical, Derevyanchenko returned, sat on a folding metal chair with his hands clasped behind his head, and stretched out his legs. Then he moved to the sofa and adopted a similar position.

A handful of people came and went – Sergiy’s wife, Iryna, Pat Connolly (Keith’s father), PBC representative Sam Watson.

Co-trainers Andre Rozier and Gary Stark, Sergiy Konchynsky (a friend of Derevyanchenko’s since childhood), and cutman Mike Bazzel were a constant presence. Unlike Jacobs-Derevyanchenko, when Rozier (who trained both men) worked Danny’s corner, Sergiy’s team was now unified.

At nine o’clock, Sergiy rose from the sofa, walked over to a shrink-wrapped package that contained 24 bottles of Aquafina, opened a bottle, and took a sip. Then he began changing into his boxing gear, folding his street clothes neatly before putting them aside.

At 9:05, referee Harvey Dock came in and gave Sergiy his pre-fight instructions: “There is no three-knockdown rule . . . If your mouthpiece comes out . . . If you score a knockdown . . .”

When Dock was done, Keith Connolly raised the issue of Golovkin hitting opponents on the back of the head and asked the referee to affirm that he would take strict action in the event of a foul. Dock promised to enforce the rules. Connally repeated his point and got the same answer the second time around.

At 9:15, Stitch Duran (Golovkin’s cutman) came in to watch Stark wrap Sergiy’s hands.

Rozier fiddled with the TV remote until the DAZN undercard appeared on the screen.

At 9:34, the wrapping was done.

Sergiy began stretching on his own.

Connolly handed him a smart phone. Al Haymon was calling to wish Sergiy well. The conversation was short, a ten-second best wishes for the fight.

Sergiy put a white towel on the floor and continued stretching. When that was done, he stood up and Stark led him through more stretching exercises.

Konchynsky approached Maggie Lange (the lead New York State Athletic Commission inspector in the room) and showed her a silver cannister labeled “Boost Oxygen.”

“Is it all right if we use this?”

“What is it?” Lange countered.

“Oxygen.”

“I don’t know,” Lange said. “Let’s go for a ruling.”

Konchynsky and the inspector left the room to consult with the powers that be.

Derevyanchenko began shadow boxing.

“It’s your night, bro,” Rozier told him.

Konchynsky and Lange returned. The powers that be had said “no” to Boost Oxygen.

Stark gloved Derevyanchenko up.

Sergiy pounded his gloves together and hit the pads with the trainer.

Mike Bazzel greased him down.

Rozier led the group in a brief prayer.

Golovkin’s image appeared on the TV monitor. If he and Sergiy weren’t about to fight each other, one could imagine them sitting side-by-side in someone’s living room watching the fight together on television. By virtue of their origins and trade, they had more in common than most people in the arena.

Sergiy shadow boxed a bit more, then paced back and forth, deep in thought. He had followed these rituals many times before. But the stakes had never been this high. Glory and a possible eight-figure payday for his next fight if he won. And the very real possibility that he would be physically damaged before the night was done. This wasn’t a movie about life. It was the real thing. More than anyone else, fighters know what’s at stake every time they enter the ring.

*

Even “name” fighters have been struggling at the gate lately in the United States. Golovkin was no exception. In the days leading up to the fight, a large number of tickets had been given away by the promotion. Even so, the announced attendance of 12,577 was far short of capacity.

Golovkin had fought in the main arena at Madison Square Garden on four previous occasions and twice in MSG’s smaller Hulu Theater. He was the crowd favorite.

Both men started cautiously. Then, two minutes into round one, Derevyanchenko ducked low as Golovkin threw a right hand. The punch landed just behind the top of Sergiy’s head and put him down.

“He hit me in the back of the head,” Derevyenchenko said later. “I didn’t see the punch, but it didn’t really affect me that much. I got up and I wasn’t really hurt, so it was nothing too bad.”

But the round had been up for grabs until that point. Now it was a two-point round for Golovkin. And the next stanza brought something very bad for Sergiy. A left hook landed cleanly and opened an ugly gash on his right eyelid.

Referee Harvey Dock mistakenly ruled that the cut had been caused by an accidental head butt. And because the New York State Athletic Commission doesn’t allow for instant video review, that ruling stood although it’s unclear what information was transmitted to the fighters’ corners.

Be that as it may, Derevyanchenko was now at a distinct disadvantage. Cutman Mike Bazzel swabbed adrenaline into the cut and applied pressure after every round. But he was never able to completely stop the flow of blood. The dripping was a distraction. And as the bout progressed, Sergiy had increasing difficulty seeing Golovkin’s punches coming.

“The cut really changed the fight,” Sergiy said afterward. “I couldn’t see at times. And he was targeting the eye.”

Now Derevyanchenko was in a hole. But a fighter can’t let his mind wander to what happened the round before or several punches ago. He has to stay in the moment.

Sergiy’s response to adversity was to fight more aggressively. “When I started moving [in the first two rounds],” he explained later, “I felt like I was giving him room and I was getting hit with those shots that he threw. That’s why I started taking the fight to him and getting closer and not giving him room to maneuver.”

The strategy worked. Golovkin appeared to have the heavier hands. But Derevyanchenko began winning the war in the trenches. Several body shots hurt Gennady. He seemed to be tiring and losing his edge. One had the feeling that, if Sergiy’s eye held up and he was able to take the fight into the late rounds, an upset was possible. Golovkin had a look about him that said, “Either I’m getting old or you’re good.”

Brutal warfare followed. Choose your metaphor. Two men walking through fire. A dogfight between pitbulls.

The crowd roared through it all.

Neither man shied away from confrontations. In round eleven, Sergiy’s left eyelid (the one that hadn’t been cut) noticeably puffed up. It round twelve, it looked like a balloon. Both men dug as deep as it was possible to dig. And then some.

Most ringside observers thought Derevyanchenko won the fight by a narrow margin. But before the decision of the judges was announced, DAZN blow-by-blow commentator Brian Kenny observed, “You come into the fight with a certain mindset. Golovkin is the favorite. You expect him to do better.”

That mindset was reflected in the judges verdict: Frank Lombardi 115-112, Eric Marlinski 115-112, Kevin Morgan 114-113 – all for Golovkin. The crowd booed when the decision was announced. They weren’t booing Gennady, who had fought as heroically as Sergiy. They were booing the decision. A draw would have been equitable. One point in favor of Golovkin was within the realm of reason. 115-112 (7 rounds to 5 for Gennady) was bad judging.

Golovkin himself seemed to acknowledge the iffy nature of the decision when he said in the ring after the fight, “I want to say thank you so much to my opponent. He’s a very tough guy. This is huge experience for me. This was a tough fight. I need to still get stronger in my camp. I need a little bit more focus. Right now, it’s bad day for me. It’s a huge day for Sergiy. Sergiy was ready. He showed me such a big heart. I told him, ‘Sergiy, this is best fight for me.'”

That thought was echoed by Johnathon Banks (Golovkin’s trainer), who later acknowledged, “I don’t remember the exact scores, but I thought the fight was a lot closer than that.”

After the fight, the skin around Derevyanchenko’s eyes was swollen to the point where each eye was almost shut. His right eyelid was purple, bulging, and sliced open. There was a huge pocket of blood beneath his left eyelid.

Neither fighter attended the post-fight press conference. Sergey Konchynsky came into Derevyanchenko’s dressing room, packed Sergiy’s civilian clothes in a gym bag, and left. Then he went with Derevyanchenko to Bellevue Hospital where they were joined by Golovkin who was brought in as a precautionary measure.

“It took forever at the hospital,” Keith Connolly recalls. “Sergiy and Gennady might have been the only patients there who weren’t handcuffed to a gurney.”

Derevyanchenko was stitched up and released from the hospital around 5:00 AM. Then he, Iryna, Konchynsky, and Connolly went to the Tick-Tock Diner on 34th Street where Sergiy ate blueberry pancakes before going back to his hotel to sleep.

The middleweight division has some quality fighters. Derevyanchenko can now be counted among them. The way he fought against Golovkin on Saturday night raised his profile. Big-money bouts that might be available to him in the near future include a rematch against Gennady or an even more lucrative outing against Canelo Alvarez on Cinco de Mayo weekend in 2020. Alternatively, Al Haymon might come to manager Keith Connolly with an offer for Sergiy to fight WBC 160-pound beltholder Jermall Charlo.

But for now, let’s celebrate the courage and fortitude that Sergiy Derevyanchenko and Gennady Golovkin showed in the ring while battling against one another. And remember: Fighters are damaged every time they step into the ring. Fights like this take a heavy toll on both fighters. And sometimes the winner is damaged more than the loser.

PHOTO (c): Wojtek Urbanek

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – A Dangerous Journey; Another Year Inside Boxing – is being published this autumn by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoOscar Duarte and Regis Prograis Prevail on an Action-Packed Fight Card in Chicago

-

Featured Articles1 week ago

Featured Articles1 week agoThe Hauser Report: Cinematic and Literary Notes

-

Book Review4 days ago

Book Review4 days agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoRemembering Dwight Muhammad Qawi (1953-2025) and his Triumphant Return to Prison

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoOleksandr Usyk Continues to Amaze; KOs Daniel Dubois in 5 One-Sided Rounds