Featured Articles

Avila Perspective, Chap. 80: Boxing 101 (Part Two)

Little did I know, not everyone was taught how to jab at three years old or put in boxing rings to spar other kids.

Welcome to my life.

On one side of my family – my mother’s side that hailed from Arizona – was a great grandfather, Battling Ortega, who fought more than 70 professional fights beginning in 1916. My great grandmother’s side also produced one world champion, Manuel Ortiz, who fought in the 1930s to the 1950s.

My father’s side was not as decorated in boxing as my mother’s family, but beginning with my grandfather Jesus Avila in World War I, the prize ring was where he made extra money while working for railroad companies in the east coast. His sons would also box during World War II but not professionally. My father Amado was the only professional boxer on his side of the family.

When I was three years old my father Amado “Mara” Avila was boxing at the Olympic Auditorium and would teach me how to stand, throw combinations and block punches. After spending the mornings at the Main Street Gym in Los Angeles with his trainer Harry Kabakoff, he would return home and teach me boxing skills as my mother prepared dinner.

It was decided early for me that I be taught boxing so as not to be bullied by other kids on the East L.A. playgrounds. My mother had seen kids push me around in the sand box and was frustrated by my failure to respond. My mom, bless her, grew up in East L.A. and knew what to expect on the streets.

Boxing became part of my daily world as each day was spent working on combinations and defense. By the time I was four years old my father put me in the boxing ring against older kids. I lost almost every fight in every tournament for three years.

Maybe losing is what made baseball so appealing to me. While I lost most of my bouts in boxing to older kids, in baseball I was above average as a pitcher from an early age. But my father wanted me to continue boxing and I did. I got better as I got older. By the time I was nine years old I stopped losing. But it was not my sport of choice.

By the age of 14 I had grown rather tall and at nearly six feet in height and 135 pounds I had a tremendous advantage in boxing. My father had stopped boxing because of a head injury suffered after a fight at the Olympic Auditorium. Though naturally a featherweight, during a scheduled fight he failed to make weight and instead of canceling his slot, he opted to fight a lightweight and was promptly knocked down by the bigger fighter. After the knockdown he tried to continue fighting but suffered blindness that lasted for several minutes. He never boxed again.

By the time I was 10 years old baseball consumed most of my time away from school. Though I kept boxing occasionally on smokers, it was baseball that was my true passion as I played year after year in City Terrace Park and Belvedere Park both in East L.A.

When I was 14 I attended a fight card at the Olympic Auditorium. Later, at a restaurant on Figueroa in downtown L.A., my father’s former trainer Harry Kabakoff approached me with an offer to train me professionally.

I turned him down.

Though I was now winning all of my fights, I knew that boxing on a professional level was quite different. It’s a very unforgiving sport and even with advantages in height, speed or power, it’s not enough. Prizefighters are a different breed. The good ones have a killer instinct and a very high degree of pain tolerance.

Some guys shrink into a shell when they are hit with a painful blow, other’s draw into a survival mode. And still others wake up suddenly more alert than ever as if a light was turned on. And a small few can see the road starkly clearer as time seems to slow down and they slip into a higher fighting mode. These are your champions.

As a member of a boxing family we would spend Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s sitting on sofas watching television and talking about the fight game. It was a favorite subject of my great grandfather who spoke about fighting Benny Leonard, Soldier Bartfield and many others. Our family consisted of boxers on all sides so it was the natural topic.

Of course, I had no idea who Benny Leonard was but according to my great grandfather, he was the best fighter he had ever faced. And he fought dozens of world champions in a day when there was only one world champion, not four to six world champions like today. His stories about the old days were pretty interesting. They made good money in those days even though it was 100 years ago. Prizefighting was extremely popular. It helped him buy a house in East L.A. down the street by the old Resurrection Gym. It’s now where Oscar De La Hoya Animo High School stands.

The stories we shared around the dinner table were engrained in me along with my own experiences in the boxing ring. For years I forgot all about them until boxing returned to my life and something woke up in me.

Boxing reclaimed me.

2010s the Decade of Growth

One of the worst economic downturns in world history failed to kill the sport of prizefighting. Instead, boxing remained one of the main attractions utilized by Las Vegas casinos to lure customers through their glitzy doors.

Floyd Mayweather picked up the baton from Oscar De La Hoya as the money-maker for the sport in the 2010s and was the fighter everyone wanted to face. His ascent to the top as a gate attraction began with a victory over Zab Judah in 2006 and was steadily moving upward monetarily.

By 2010, Mayweather was the top star along with Filipino superstar Manny “Pacman” Pacquiao. One of the top fights that year was his battle against Sugar Shane Mosley at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. Mayweather escaped after absorbing a big right hand bomb from the Pomona fighter.

Later that same year, Mosley fought Sergio Mora to a disputed draw at Staples Center in Los Angeles.

East L.A.’s Mora had been one of those fighters I spotted early in his development. During his first pro bout at a boxing card in Anaheim, I could see he had a different fighting style along with athleticism that was going to be hard to beat. I predicted in his fourth fight that he would one day be a world champion. When he fought Vernon Forrest, I predicted Mora would win and he did. To my knowledge, only Doug Fischer and I predicted the victory.

As a boxing journalist it’s important to watch young fighters develop early. Anyone can predict greatness for someone winning an Olympic gold medal, but there’s always someone who sneaks in through the cracks and makes it to the top. Those are the real stories in prizefighting.

Another guy named Sergio was slipping through the cracks from South America. He was a super welterweight named Sergio Martinez. 2010 was a spectacular year for the slick fighting Argentine named “Maravilla” as he defeated Kelly Pavlik in April and knocked out Paul Williams in the second round of a November fight. He was named the Fighter of the Year by the WBC and was recognized as such in a ceremony in San Bernardino along with Tim “Desert Storm” Bradley for an extremely good year.

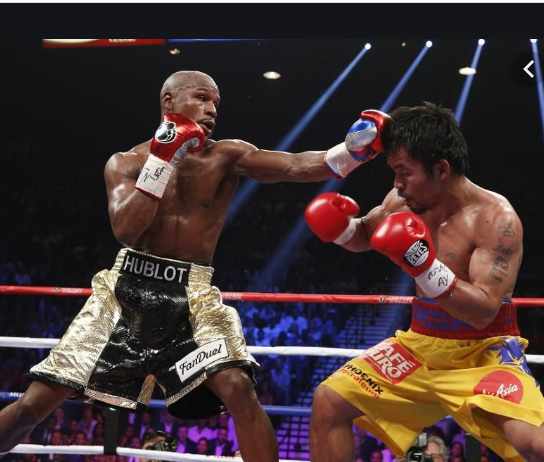

The biggest grossing fight of all time took place when Mayweather and Pacquiao finally met on May 2, 2015. After years of debate the two stars met in Las Vegas and their pay-per-view fight generated more than 4 million buys. It remains the most successful pay-per-view boxing match of all time. Mayweather’s victory set him apart as the most successful fighter in terms of financial gain. He has cleared more than $1 billion as a prizefighter according to Forbes Magazine.

Around this time another middleweight was stirring up things in the boxing world after moving from Germany to Big Bear, California. His name – Gennady Golovkin.

GGG

Big Bear, California had been a favorite spot for prizefighters for several decades. Oscar De La Hoya, Mike Tyson, Fernando Vargas, Floyd Mayweather Jr. and many others throughout the years had prepared for mega fights in the mountain resort spot popular for skiing at its 12,000-feet elevation. It’s located in the Inland Empire area east of Los Angeles County.

Abel Sanchez, a building contractor and boxing trainer, had personally built a compound at Big Bear and was preparing fighters down the street from Sugar Shane Mosley’s training site.

When K2 Promotions signed Golovkin it was Tom Loeffler who brought Golovkin to Sanchez and together they all made history and a lot of money with their “Mexican style” boxing.

Loeffler invited me to see Golovkin train at the mountain headquarters and his power and skills were instantly impressive. It took a few years for the rest of the world to catch on and believe in GGG.

Over the decades my experience as a boxer and as a journalist gave me insight into what separates great fighters from normal fighters. With Golovkin it was the pure power in his fists for a man his size. There was a certain sound when he hit a heavy bag that was different. His skills were also pretty sound, he didn’t have flaws in his technique that I often see with other fighters. Some drop their hands during combinations, others expose their chin to counters and still others telegraph their punches so badly a blind man can see them.

Golovkin was tight from the start.

Before he fought in front of American audiences on HBO it was clear Golovkin was going to be a star. It just took a little time for the rest of the world to be convinced.

Around this same time another fighter moved into the Inland Empire area named Mikey Garcia. He had purchased a house in Moreno Valley, California and moved from Oxnard to set up shop. Within a couple of years his family would follow including brother Robert Garcia and father Eduardo Garcia.

It was a move that would soon change the boxing landscape as the Garcias opened a gym in Riverside, California. Soon, many top fighters from around the country and world would sign with the Garcias and begin training in the hills of Riverside.

More and more boxers were arriving to the many gyms throughout the Inland Empire from all over the world. An explosion of talent arrived and very few outside of the elite had any idea it was transpiring.

Fighters like Golovkin, Mikey Garcia, Tim Bradley, Shane Mosley, and even Terence Crawford and Andy Ruiz were working out in the Inland Empire gyms.

Because of its 60 miles or more distance from Los Angeles few reporters covering the sport made the trek to visit the more than 35 gyms scattered throughout the Inland Empire.

Social Media

Though my own beginning as a boxing journalist began with newspapers, it’s not difficult for me to point out the poor coverage and ineptitude of those covering the sport for print.

The development of boxing web sites easily took over coverage of the sport with various names like SecondsOut.com, House of Boxing, Fight News and The Sweet Science to name a few. Now there are literally hundreds of boxing sites throughout the world.

Most coverage is devoted to the top echelon of the sport of prizefighting, but a few make a determined effort to trace the beginnings of pro boxers as they make their journeys.

Only one newspaper, the Riverside Press-Enterprise was at ringside when Saul “Canelo” Alvarez made his American debut at Morongo Casino in Southern California.

When Alvarez fought Mayweather in 2013, his journey was well-documented by most boxing web sites, but newspapers – aside from the Riverside Press-Enterprise – were forced to play catchup.

Mayweather easily defeated Alvarez on points and though he never hurt the Mexican redhead, he did deliver an important teaching lesson that “Canelo” and his team never forgot. Defense was equally important as offense and it served them well.

Eddy Reynoso, the trainer for Alvarez, has never wavered from expressing how much they learned from that fight against Mayweather in September 2013.

“From people like Mayweather, we learned a lot. It wasn’t for nothing, he was the best in the ring,” said Reynoso last month. “Fighting against Mayweather you learn a lot of different levels. The loss teaches you to do better.”

Now, seven years later, Canelo Alvarez reigns as the top money-maker and a multi-divisional world champion.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 330: Matchroom in New York plus the Latest on Canelo-Crawford

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoVito Mielnicki Jr Whitewashes Kamil Gardzielik Before the Home Folks in Newark

-

Featured Articles8 hours ago

Featured Articles8 hours agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatching Up with Clay Moyle Who Talks About His Massive Collection of Boxing Books

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMore Medals for Hawaii’s Patricio Family at the USA Boxing Summer Festival

-

Featured Articles7 days ago

Featured Articles7 days agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoRichardson Hitchins Batters and Stops George Kambosos at Madison Square Garden